Lexical Differences Between American and British English: a Survey Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

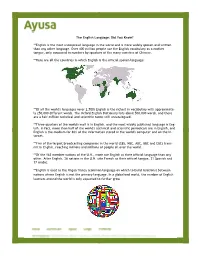

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

AUSTRALIAN FOOD SLANG Abstract

UNIWERSYTET HUMANISTYCZNO-PRZYRODNICZY IM. JANA DŁUGOSZA W CZĘSTOCHOWIE Studia Neofilologiczne 2020, z. XVI, s. 151–170 http://dx.doi.org/10.16926/sn.2020.16.08 Dana SERDITOVA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1206-8507 (University of Heidelberg) AUSTRALIAN FOOD SLANG Abstract The article analyzes Australian food slang. The first part of the research deals with the definition and etymology of the word ‘slang’, the purpose of slang and its main characteristics, as well as the history of Australian slang. In the second part, an Australian food slang classification consisting of five categories is provided: -ie/-y/-o and other abbreviations, words that underwent phonetic change, words with new meaning, Australian rhyming slang, and words of Australian origin. The definitions of each word and examples from the corpora and various dictionaries are provided. The paper also dwells on such particular cases as regional varieties of the word ‘sausage’ (including the map of sausages) and drinking slang. Keywords: Australian food slang, Australian English, varieties of English, linguistic and culture studies. Australian slang is a vivid and picturesque part of an extremely fascinating variety of English. Just like Australian English in general, the slang Down Under is influenced by both British and American varieties. Australian slang started as a criminal language, it moved to Australia together with the British convicts. Naturally, the attitude towards slang was negative – those who were not part of the criminal culture tried to exclude slang words from their vocabulary. First and foremost, it had this label of criminality and offense. This attitude only changed after the World War I, when the soldiers created their own slang, parts of which ended up among the general public. -

1/4 Here You Can Find an Overview of the 50 Must

Here you can find an overview of the 50 must-know British slang words and phrases. Print out this PDF document and practice them with your British Tandem partner: Bloke “Bloke” would be the American English equivalent of “dude.” It means a “man.” Lad In the same vein as “bloke,” “lad” is used, however, for boys and younger men. Bonkers Not necessarily intended in a bad way, “bonkers” means “mad” or “crazy.” Daft Used to mean if something is a bit stupid. It’s not particularly offensive, just mildly silly or foolish. To leg it This term means to run away, usually from some trouble! “I legged it from the Police.” These two words are British slang for drunk. One can get creative here Trollied / Plastered and just add “-ed” to the end of practically any object to get across the same meaning eg. hammered. Quid This is British slang for British pounds. Some people also refer to it as “squid.” Used to describe something or someone a little suspicious or Dodgy questionable. For example, it can refer to food which tastes out of date or, when referring to a person, it can mean that they are a bit sketchy. This is a truly British expression. “Gobsmacked” means to be utterly Gobsmacked shocked or surprised beyond belief. “Gob” is a British expression for “mouth”. Bevvy This is short for the word “beverages,” usually alcoholic, most often beer. Knackered “Knackered” is used when someone is extremely tired. For example, “I was up studying all night last night, I’m absolutely knackered.” Someone who has “lost the plot” has become either angry, irrational, Lost the plot or is acting ridiculously. -

Intrinsic Motivation

Reading and the Native American Learner Research Report Dr. Terry Bergeson State Superintendent of Public Instruction Andrew Griffin, Ed.D. Director Higher Education, Community Outreach, and Staff Development Denny Hurtado, Program Supervisor Indian Education/Title I Program This material available in alternative format upon request. Contact Curriculum and Assessment, 360/753-3449, TTY 360/664-3631. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction complies with all federal and state rules and regulations and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, age, or marital status. June 2000 ii This report was prepared by: Joe St. Charles, M.P.A. Magda Costantino, Ph.D. The Evergreen Center for Educational Improvement The Evergreen State College In collaboration with the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Office of Indian Education With special thanks to the following reviewers: Diane Brewer Sally Brownfield William Demmert Roy DeBoer R. Joseph Hoptowit Mike Jetty Acknowledgement to Lynne Adair for her assistance with the project. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................3 THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION ................................................................... 9 SOURCES OF EDUCATIONAL DIFFICULTIES -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

Two Introductory Texts on Using Statistics for Linguistic Research and Two Books Focused on Theory

1. General The four books discussed in this section can be broadly divided into two groups: two introductory texts on using statistics for linguistic research and two books focused on theory. Both Statistics for Linguists: A Step-by-Step Guide for Novices by David Eddington and How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis by Natalia Levshina offer an introduction to statistics and, more specifically, how it can be applied to linguistic research. Covering the same basic statistical concepts and tests and including hands- on exercises with answer keys, the textbooks differ primarily in two respects: the choice of statistical software package (with subsequent differences reflecting this choice) and the scope of statistical tests and methods that each covers. Whereas Eddington’s text is based on widely used but costly SPSS and focuses on the most common statistical tests, Levshina’s text makes use of open-source software R and includes additional methods, such as Semantic Vector Spaces and making maps, which are not yet mainstream. In his introduction to Statistics for Linguists, Eddington explains choosing SPSS over R because of its graphical user interface, though he acknowledges that ‘in comparison to SPSS, R is more powerful, produces better graphics, and is free’ (p. xvi). This text is therefore more appropriate for researchers and students who are more comfortable with point-and-click computer programs and/or do not have time to learn to manoeuvre the command-line interface of R. Eddington’s book also has the goal of being ‘a truly basic introduction – not just in title, but in essence’ (p. -

British Or American English?

Beteckning Department of Humanities and Social Sciences British or American English? - Attitudes, Awareness and Usage among Pupils in a Secondary School Ann-Kristin Alftberg June 2009 C-essay 15 credits English Linguistics English C Examiner: Gabriella Åhmansson, PhD Supervisor: Tore Nilsson, PhD Abstract The aim of this study is to find out which variety of English pupils in secondary school use, British or American English, if they are aware of their usage, and if there are differences between girls and boys. British English is normally the variety taught in school, but influences of American English due to exposure of different media are strong and have consequently a great impact on Swedish pupils. This study took place in a secondary school, and 33 pupils in grade 9 participated in the investigation. They filled in a questionnaire which investigated vocabulary, attitudes and awareness, and read a list of words out loud. The study showed that the pupils tend to use American English more than British English, in both vocabulary and pronunciation, and that all of the pupils mixed American and British features. A majority of the pupils had a higher preference for American English, particularly the boys, who also seemed to be more aware of which variety they use, and in general more aware of the differences between British and American English. Keywords: British English, American English, vocabulary, pronunciation, attitudes 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner.