The Origins of Ethno/National Separatist Terrorism: a Cross- National Analysis of the Background Conditions of Terrorist Campaigns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Naming of Sea Areas in Modern Atlases and Implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan Case

Dual naming of sea areas in modern atlases and implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan case Rainer DORMELS* Dual naming is, to varying extents, present in nearly all atlases. The empirical research in this paper deals with the dual naming of sea areas in about 20 atlases from different nations in the years from 2006 to 2017. Objective, quality, and size of the atlases and the country where the atlases originated from play a key role. All these characteristics of the atlases will be taken into account in the paper. In the cases of dual naming of sea areas, we can, in general, differentiate between: cases where both names are exonyms, cases where both names are endonyms, and cases where one name is an endonym, while the other is an exonym. The goal of this paper is to suggest a typology of dual names of sea areas in different atlases. As it turns out, dual names of sea areas in atlases have different functions, and in many atlases, dual naming is not a singular exception. Dual naming may help the users of atlases to orientate themselves better. Additionally, dual naming allows for providing valuable information to the users. Regarding the naming of the sea between Korea and Japan present study has achieved the following results: the East Sea/Sea of Japan is the sea area, which by far showed the most use of dual naming in the atlases examined, in all cases of dual naming two exonyms were used, even in atlases, which allow dual naming just in very few cases, the East Sea/Sea of Japan is presented with dual naming. -

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information Index 1995 Mining Law, 191 Authoritarianism, 4, 11–13, 47, 64, 230–31, 1996 Agreement (with MNLF), 21, 155–56, 232, 239–40, 245 157–59, 160, 162, 165–66 Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, 142, 150, 153, 157, 158–61, 167–68 Abu Sayaff, 14, 163, 170 Autonomy, 4, 12, 25, 57, 240 Accelerated development unit for Papua and Aceh, 20, 72, 83, 95, 102–3, 107–9 West Papua provinces, 131 Cordillera, 21, 175, 182, 186, 197–98, 200 Accommodation. See Concessions federalism, 37 Aceh Peace Reintegration Agency, 99–100 fiscal resources, 37 Aceh Referendum Information Centre, 82, 84 fiscal resources, Aceh, 74, 85, 89, 95, 98, Aceh-Nias Rehabilitation and Reconstruction 101, 103, 105 Agency, 98 fiscal resources, Cordillera, 199 Act of Free Choice, 113, 117, 119–20, 137 fiscal resources, Mindanao, 150, 156, 160 Administrative Order Number 2 (Cordillera), fiscal resources, Papua, 111, 126, 128 189–90, See also Ancestral domain Indonesia, 88 Al Hamid, Thaha, 136 jurisdiction, 37 Al Qaeda, 14, 165, 171, 247 jurisdiction, Aceh, 101 Alua, Agus, 132, 134–36 jurisdiction, Cordillera, 186 Ancestral Domain, 166, 167–70, 182, 187, jurisdiction, Mindanao, 167, 169, 171 190, 201 jurisdiction, Papua, 126 Ancestral Land, 184–85, 189–94, 196 Malay-Muslims, 22, 203, 207, 219, 224 Aquino, Benigno Jr., 143, 162, 169, 172, Mindanao, 20, 146, 149, 151, 158, 166, 172 197, 199 Papua, 20, 122, 130 Aquino, Butz, 183 territorial, 27 Aquino, Corazon. See Aquino, Cory See also Self-determination Aquino, Cory, 17, 142–43, 148–51, 152, Azawad Popular Movement, Popular 180, 231 Liberation Front of Azawad (FPLA), 246 Armed Forces, 16–17, 49–50, 59, 67, 233, 236 Badan Reintegrasi Aceh. -

Use Bullets Against Stone-Pelters, Traitors: JK Minister

www.thenorthlines.com www.epaper.northlines.com 3 FORECAST JAMMU Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 21-Apr 28.0 40.0 Partly cloudy sky in the morning hours becoming generally cloudy sky 22-Apr 26.0 38.0 hunderstorm with rain 23-Apr 24.0 37.0 Thunderstorm with rain 3 DAY'S FORECAST SRINAGAR Date Min Temp Max Temp Weather 21-Apr 12.0 24.0 Thunderstorm with rain 22-Apr 11.0 22.0 Thunderstorm with rain 23-Apr 9.0 20.0 Thunderstorm with rain Minister asks for optimum utilization of northlinesPhoto exhibition on celebrating the JK Bank hires Delloitte as their Auqaf assets overhaul Consultants diversity inaugurated Minister of State for Hajj and Auqaf JK Bank today entered into an Speaker, J&K Legislative Assembly Syed Farooq Ahmad Andrabi today agreement with M/S Delloitte thereby Kavinder Gupta inaugurated a photo laid foundation for renovation and engaging them as their consultants for exhibition on the theme 'celebrating 3 repairs work of Qadeem Jamia providing consultancy services on diversity' organized by the Masjid Bahu Fort.... 4 Business Plan .... 5 INSIDE Department of ..... Vol No: XXII Issue No. 95 21.04.2017 (Friday) Daily Jammu Tawi Price ` 2/- Pages-12 Regd. No. JK|306|2014-16 What Azaadi? Use bullets against Officer 'saved lives' by tying man to Military cannot be subjected to jeep in Kashmir: Madhav FIR for its Operations: Army stone-pelters, traitors: JK minister NL CORRESPONDENT Kashmir or Manipur, we are said the current Kashmir boys. He also did not allow NEW DELHI, APR 20 facing the same local bias. -

Page-1Final.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Vol No. 53 No. 282 JAMMU, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2017 REGD.NO.JK-71/15-17 14 Pages ` 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 Vohra meets Rajnath 2 cops, OGW held for supplying arms to HM NEW DELHI, Oct 11: Jammu and Kashmir Governor N N Vohra today met Home Minister Rajnath Singh 2 Garud commandos, 2 militants killed and discussed with him various issues, including the security situation in the state. Fayaz Bukhari while another identified as which two militants identified place in which two militants During the 20-minute meet- Surjeet Miulind Khairum was as Nasrullah Mir alias Anna were killed and two IAF com- ing, the Governor briefed the SRINAGAR, Oct 11: Two seriously injured. The injured son of Nazir Ahmad Mir resi- mandos were killed. Home Minister about the pre- militants and two Indian Air dent of Mir Mohalla Verdi said that the militants vailing situation along the bor- Force (IAF) commandos were Hajin and foreign were involved in many attacks der with Pakistan, which has killed in an encounter in militant Ali Bai alias including killing of BSF Jawan been violating ceasefire regu- Bandipora district of North Maaz alias Abu Mohammad Ramzan alias larly, official sources said. Kashmir early today while Bakker were killed. rameez at his home, with knives The constitution of a study Police arrested two cops and Two AK riles, one and then fired indiscriminately, in which he was killed and his (Contd on page 4 Col 5) an Over Ground Worker pistol, 19 pistol (OGW) of militants for sup- rounds, one grenade, old aged father Ghulam Ahmad Singh takes over plying arms and ammunition two pouches and Parray, two elder brothers to Hizbul Mujahideen in other ammunition Mohammad Afzal Parray, Javid as GOC 16 Corps Shopian district of South was recovered from Ahmad Parray and paternal aunt Excelsior Correspondent Kashmir. -

269 Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant General 102–3

Index Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Turkmenistan and 88 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant US and 83, 99, 143–4, 195, General 102–3 252, 253, 256 Abeywardana, Lakshman Yapa 172 Uyghurs and 194, 196 Abu Ghraib 119 Zaranj–Delarum link highway 95 Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) 251, 260 Africa 5, 244 Abuza, Z. 43, 44 Ahmad Humam 24 Aceh 15–16, 17, 31–2 Aimols 123 armed resistance and 27 Akbar Khan Bugti, Nawab 103, 104 independence sentiment and 28 Akhtar Mengal, Sardar 103, 104 as Military Operation Zone Akkaripattu- Oluvil area 165 (DOM) 20, 21 Aksu disturbances 193 peace process and Thailand 54 Albania 194 secessionism 18–25 Algeria Aceh Legislative Council 24 colonial brutality and 245 Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) 24 radicalization in 264 Aceh Referendum Information Centre Ali Jan Orakzai, Lieutenant General 103 (SIRA) 22, 24 Al Jazeera 44 Acheh- Sumatra National Liberation All Manipur Social Reformation, women Front (ASNLF) 19 protesters of 126–7 Aceh Transition Committee (Komite All Party Committee on Development Peralihan Aceh) (KPA) 24 and Reconciliation ‘act of free choice’, 1969 Papuan (Sri Lanka) 174, 176 ‘plebiscite’ 27 All Party Representative Committee Adivasi Cobra Force 131 (APRC), Sri Lanka 170–1 adivasis (original inhabitants) 131, All- Assam Students’ Union (AASU) 132 132–3 All- Bodo Students’ Union–Bodo Afghanistan 1–2, 74, 199 Peoples’ Action Committee Balochistan and 83, 100 (ABSU–BPAC) 128–9, 130 Central Asian republics and 85 Bansbari conference 129 China and 183–4, 189, 198 Langhin Tinali conference 130 India and 143 al- Qaeda 99, 143, -

The Geographic Limits to Modernist Theories of Intra-State Violence

The Power of Ethnicity?: the Geographic Limits to Modernist Theories of Intra-State Violence ERIC KAUFMANN Reader in Politics and Sociology, Birkbeck College, University of London; Religion Initiative/ISP Fellow, Belfer Center, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Box 134, 79 John F. Kennedy St., Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] ——————————————————————————————————————————— Abstract This paper mounts a critique of the dominant modernist paradigm in the comparative ethnic conflict literature. The modernist argument claims that ethnic identity is constructed in the modern era, either by instrumentalist elites, or by political institutions whose bureaucratic constructions give birth to new identities. Group boundary symbols and myths are considered invented and flexible. Territorial identities in premodern times are viewed as either exclusively local, for the mass of the population, or ‘universal’, for elites. Primordialists and ethnosymbolists have contested these arguments using historical and case evidence, but have shied away from large-scale datasets. This paper utilizes a number of contemporary datasets to advance a three-stage argument. First, it finds a significant relationship between ethnic diversity and three pre- modern variables: rough topography, religious fractionalization and world region. Modernist explanations for these patterns are possible, but are less convincing than ethnosymbolist accounts. Second, we draw on our own and others’ work to show that ethnic fractionalization (ELF) significantly predicts the incidence of civil conflict, but not its onset . We argue that this is because indigenous ethnic diversity is relatively static over time, but varies over space. Conflict onsets, by contrast, are more dependent on short-run changes over time than incidents, which better reflect spatially-grounded conditioning factors. -

Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with Its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)

ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD Area Study Centre (Russia, China & Central Asia) UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (DECEMBER 2016) ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD A dissertation submitted to the University of Peshawar in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (DECEMBER 2016) i AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, Mr. Ayaz Ahmad hereby state that my PhD thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from this University of Peshawar or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my graduation the University has the right to withdraw my PhD degree. AYAZ AHMAD Date: December 2016 ii PLAGIARISM UNDERTAKING I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any other person. Small contribution/help wherever taken has been duly acknowledged and that complete thesis has been written by me. I understand the zero tolerance policy of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) and University of Peshawar towards plagiarism. Therefore I as an Author of the above-titled thesis declare that no portion of my thesis has been plagiarized and any material used as a reference is properly referred/cited. -

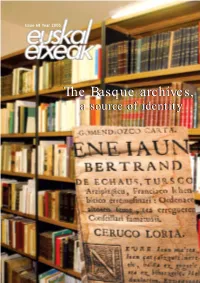

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

'Growing up Under the Shadow of the Gun'

‘Growing up under the shadow of the gun’ Research on the lives of women who grew up with the realities of the Armed Force Special Powers Act in Kashmir. Name of student: D.S.C. Boerema Student number: 5710685 Date of Submission: 18-07-2018 University of Utrecht A Thesis submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Studies & Human Rights. Supervisor: prof. dr. ir. Georg Frerks Date of Submission: 18-07-2018 Programme trajectory: Research and thesis Writing (30ECT) Word count: 26000 Abstract Implemented in 1990, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act gives the Indian army blanket immunity to arrest, interrogate, kill and rape Kashmiri’s if they are considered a safety threat. At this moment seventy per cent of Kashmir’s population is under the age of thirty-five. This means that most of them have grown up knowing no other reality than that of living in a heavily securitized zone. This thesis is written based on the memories and experiences of thirty women who all come from Kashmir. Some of them were born just before 1990, most of them after this defining year in Kashmir history. Women’s voices are the most misunderstood and underreported in a conflict. This thesis aims to find an answer to how the securitization of Kashmir, through the AFSPA, has mobilized women to use public space as a tool for resistance in Srinagar. It finds that women mobilize to claim a space for their own identity as Kashmiri women, within a larger society that experiences an attack on its identity in the form of Indian occupation. -

Patterns of Global Terrorism 1999

U.S. Department of State, April 2000 Introduction The US Government continues its commitment to use all tools necessary—including international diplomacy, law enforcement, intelligence collection and sharing, and military force—to counter current terrorist threats and hold terrorists accountable for past actions. Terrorists seek refuge in “swamps” where government control is weak or governments are sympathetic. We seek to drain these swamps. Through international and domestic legislation and strengthened law enforcement, the United States seeks to limit the room in which terrorists can move, plan, raise funds, and operate. Our goal is to eliminate terrorist safehavens, dry up their sources of revenue, break up their cells, disrupt their movements, and criminalize their behavior. We work closely with other countries to increase international political will to limit all aspects of terrorists’ efforts. US counterterrorist policies are tailored to combat what we believe to be the shifting trends in terrorism. One trend is the shift from well-organized, localized groups supported by state sponsors to loosely organized, international networks of terrorists. Such a network supported the failed attempt to smuggle explosives material and detonating devices into Seattle in December. With the decrease of state funding, these loosely networked individuals and groups have turned increasingly to other sources of funding, including private sponsorship, narcotrafficking, crime, and illegal trade. This shift parallels a change from primarily politically motivated terrorism to terrorism that is more religiously or ideologically motivated. Another trend is the shift eastward of the locus of terrorism from the Middle East to South Asia, specifically Afghanistan. As most Middle Eastern governments have strengthened their counterterrorist response, terrorists and their organizations have sought safehaven in areas where they can operate with impunity. -

Unlversiv Micrijfilms Intemationéü 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the fîlm along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Him is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been fîlmed, you will And a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a defînite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy.