Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 9

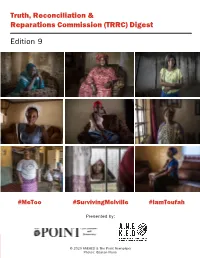

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 9 #MeToo #SurvivingMelville #IamToufah Presented by: © 2020 ANEKED & The Point Newspaper 1| Photos: ©Jason Florio The Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) is mandated to investigate and establish an impartial historical record of the nature, causes and extent of violations and abuses of human rights committed during the period of July 1994 to January 2017 and to consider the granting of reparations to victims and for connected matters. It started public hearings on 7th January 2019 and will proceed in chronological order, examining the most serious human rights violations that occurred from 1994 to 2017 during the rule of former President Yahya Jammeh. While the testimonies are widely reported in the press and commented on social media, triggering vivid discussions and questions regarding the current transitional process in the country, a summary of each thematic focus/event and its findings is missing. The TRRC Digests seek to widen the circle of stakeholders in the transitional justice process in The Gambia by providing Gambians and interested international actors, with a constructive recount of each session, presenting the witnesses and listing the names of the persons mentioned in relation to human rights violations and – as the case may be – their current position within State, regional or international institutions. Furthermore, the Digests endeavour to highlight trends and patterns of human rights violations and abuses that occurred and as recounted during the TRRC hearings. In doing so, the TRRC Digests provide a necessary record of information and evidence uncovered – and may serve as “checks and balances” at the end of the TRRC’s work. -

DAKAR, SENEGAL Onboard: 1800 Monday, October 24

Arrive: 0800 Friday, October 21 DAKAR, SENEGAL Onboard: 1800 Monday, October 24 Brief Overview: French-speaking Dakar, Senegal is the western-most city in all of Africa. As the capital and largest city in Senegal, Dakar is located on the Cape Verde peninsula on the Atlantic. Dakar has maintained remnants of its French colonial past, and has much to offer both geographically and culturally. Travel north to the city of Saint Louis (DAK 301-201 Saint Louis & Touba) and enjoy the famous “tchay bon djenn” hosted by a local family and Senegalese wrestling. Take a trip in a Pirogue to Ngor Island where surfers and locals meet. Visit the Pink Lake to see and learn from local salt harvesters. Discover the history of the Dakar slave trade with a visit to Goree Island (DAK 101 Goree Island), one of the major slave trading posts from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s, where millions of enslaved men, women and children made their way through the “door of no return.” Touba (DAK 107-301 Holy City of Touba & Thies Market), a city just a few hours inland from Dakar, is home to Africa’s second-largest mosque. Don’t leave Senegal without exploring one of the many outdoor markets (DAK 109-202 Sandaga market) with local crafts (DAK 105-301 Dakar Art Workshop) and traditional jewelry made by the native Fulani Senegalese tribe. Check out this great video on the Documentary Photography field lab from the 2015 Voyage! Highlights: Cultural Highlights: Art and Architecture: Every day: DAK 104-101/201/301/401 Pink Lake Retba & Day 2: DAK 112-201 African Renaissance, -

China-Assisted Wrestling Arena Welcomed by Senegalese Society by Hu Zexi, Zhang Penghui, Li Zhiwei, Liu Lingling from People’S Daily

China-assisted wrestling arena welcomed by Senegalese society By Hu Zexi, Zhang Penghui, Li Zhiwei, Liu Lingling from People’s Daily A China-aided arena for traditional Senegalese wrestling, a gift presented by China to the West African country, is greeted by all locals of the sports-loving country, who believe that as an epitome of bilateral cooperation, the project not only brings tangible benefits to locals, but also adds impetus for local development. “The National Grand Theater, the Museum of Black Civilization and the National Wrestling Arena, built with Chinese assistance, stand as important venues to carry forward the culture and traditions of Senegal,” Chinese President Xi Jinping wrote in a signed article published on mainstream Senegalese newspaper ahead of his state visit to the African country. The upcoming delivery of the monumental structure designed by Chinese companies and being built by them is a big event for local residents, since wrestling is a national sport that has conquered the heart of all Senegalese. As an immensely popular sport in Senegal, wrestling also means “remain true to original aspiration, and strive for glory” in local language. The modern structure, sitting on 7 hectares of land with 18,000 square meters of floor area, is soon be delivered after two-year-long construction. Senegalese government acknowledged the construction of the project in the exchange notes it inked with Chinese government in February 2014, and then signed construction contract with Hunan Construction Engineering Group in December 2015. Comparing the structure as “a precious gemstone in Dakar, capital and largest city of Senegal”, the mainstream Senegalese newspaper Le Soleil said it will “shine on the whole West Africa”. -

Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women's Writing

Through A Female Lens: Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women's Writing Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Mutunda, Sylvester Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 13:05:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194161 THROUGH A FEMALE LENS: ASPECTS OF MASCULINITY IN FRANCOPHONE AFRICAN WOMEN’S WRITING By Sylvester N. Mutunda _____________________ Copyright © Sylvester N. Mutunda 2009 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH AND ITALIAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN FRENCH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sylvester Mutunda entitled Through A Female Lens: Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women’s Writing and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Irène Assiba d’Almeida ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Jonathan Beck ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Phyllis Taoua Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Casamance, 1885-2014

MAPPING A NATION: SPACE, PLACE AND CULTURE IN THE CASAMANCE, 1885-2014 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark William Deets August 2017 © 2017 Mark William Deets MAPPING A NATION: SPACE, PLACE AND CULTURE IN THE CASAMANCE, 1885-2014 Mark William Deets Cornell University This dissertation examines the interplay between impersonal, supposedly objective “space” and personal, familiar “place” in Senegal’s southern Casamance region since the start of the colonial era to determine the ways separatists tried to ascribe Casamançais identity to five social spaces as spatial icons of the nation. I devote a chapter to each of these five spaces, crucial to the separatist identity leading to the 1982 start of the Casamance conflict. Separatists tried to “discursively map” the nation in opposition to Senegal through these spatial icons, but ordinary Casamançais refused to imagine the Casamance in the same way as the separatists. While some corroborated the separatist imagining through these spaces, others contested or ignored it, revealing a second layer of counter-mapping apart from that of the separatists. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Mark W. Deets is a retired Marine aviator and a PhD candidate in African History at Cornell University. Deets began his doctoral studies after retiring from the Marine Corps in 2010. Before his military retirement, Deets taught History at the U.S. Naval Academy. Previous assignments include postings as the U.S. Defense and Marine Attaché to Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and Mauritania (2005-2007), as a White House Helicopter Aircraft Commander (HAC) and UH-1N “Huey” Operational Test Director with Marine Helicopter Squadron One (1999-2002), and as Assistant Operations Officer and UH-1N Weapons and Tactics Instructor with the “Stingers” of Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 267 (1993-1998). -

Dakar, Senegal

DAKAR, SENEGAL Arrive: 0800 Saturday, October 31 Onboard: 1800 Tuesday, November 3 Brief Overview: French-speaking Dakar, Senegal is the western-most city in all of Africa. The capital and largest city in Senegal, Dakar is located on the Cape Verde peninsula on the Atlantic. Dakar has maintained remnants of its French colonial past, and has much to offer both geographically and culturally. Travel north to the city of Saint Louis and see the Djoudj National Bird sanctuary, home to more than 1.5 million exotic birds, including 30 different species that have made their way south from Europe. Take a trip south from Dakar to the Delta de Saloum and enjoy the rich vegetation and water activities, like kayaking on the Gambie River. Visit the Pink Lake to see and learn from local salt harvesters. Discover the history of the Dakar slave trade with a visit to Goree Island, one of the major slave trading posts from the mid 1500s to the mid 1800s, where millions of enslaved men, women and children made their way through the “door of no return.” Touba, a city just a few hours inland from Dakar, is home to Africa’s second-largest mosque. Don’t leave Senegal without exploring one of the many outdoor markets with local crafts and traditional jewelry made by the native Fulani Senegalese tribe. Highlights: Cultural Highlights: Art and Architecture: Day 1: DAK 401-101 Casamance & Mandigo Country Day 2: DAK 105-201 Art Workshop Day 1: DAK 101-101 Goree Island Day 3: DAK 108-301 Art Tour with Lunch Day 1: DAK 103-103 Welcome Reception Nature & the Outdoors: Day 2: 201-201 La Petite Cote & Senegalese Naming Day 2: DAK 302-201 Toubacouta & Saloum Delta Ceremony Day 2: DAK 303-201 Nikolo Park & Eastern Senegal Day 2: DAK 107-301 Holy City of Touba & Thies Market Day 2: DAK 102-201 Bandia Reserve & Saly TERMS AND CONDITIONS: In selling tickets or making arrangements for field programs (including transportation, shore-side accommodations and meals), the Institute acts only as an agent for other entities who provide such services as independent contractors. -

Download File

Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Timothy Roark Mangin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin This dissertation is an ethnographic and historical examination of Senegalese modern identity and cosmopolitanism through urban dance music. My central argument is that local popular culture thrives not in spite of transnational influences and processes, but as a result of a Senegalese cosmopolitanism that has long valued the borrowing and integration of foreign ideas, cultural practices, and material culture into local lifeways. My research focuses on the articulation of cosmopolitanism through mbalax, an urban dance music distinct to Senegal and valued by musicians and fans for its ability to shape, produce, re-produce, and articulate overlapping ideas of their ethnic, racial, generational, gendered, religious, and national identities. Specifically, I concentrate on the practice of black, Muslim, and Wolof identities that Senegalese urban dance music articulates most consistently. The majority of my fieldwork was carried out in the nightclubs and neighborhoods in Dakar, the capital city. I performed with different mbalax groups and witnessed how the practices of Wolofness, blackness, and Sufism layered and intersected to articulate a modern Senegalese identity, or Senegaleseness. This ethnographic work was complimented by research in recording studios, television studios, radio stations, and research institutions throughout Senegal. The dissertation begins with an historical inquiry into the foundations of Senegalese cosmopolitanism from precolonial Senegambia and the spread of Wolof hegemony, to colonial Dakar and the rise of a distinctive urban Senegalese identity that set the proximate conditions for the postcolonial cultural policy of Négritude and mbalax. -

Traditional Values and Local Community in the Formal Educational System in Senegal: a Year As a High School Teacher in Thies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2020 TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES Maguette Diame University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Indigenous Education Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Diame, Maguette, "TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES" (2020). Doctoral Dissertations. 1909. https://doi.org/10.7275/prnt-tq72 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1909 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRADITIONAL VALUES AND LOCAL COMMUNITY IN THE FORMAL EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN SENEGAL: A YEAR AS A HIGH SCHOOL TEACHER IN THIES A Dissertation Presented by MAGUETTE DIAME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 College of Education Department of Educational Policy, Research, and Administration © Copyright -

African Studies Quarterly

African Studies Quarterly Volume 14, Issue 3 March 2014 Special Issue Fed Up: Creating a New Type of Senegal through the Arts Guest Editors: Molly Krueger Enz and Devin Bryson Published by the Center for African Studies, University of Florida ISSN: 2152-2448 African Studies Quarterly Executive Staff R. Hunt Davis, Jr. - Editor-in-Chief Todd H. Leedy - Associate Editor Emily Hauser - Managing Editor Corinna Greene - Production Editor Anna Mwaba - Book Review Editor Editorial Committee Oumar Ba Ibrahim Yahaya Ibrahim Lina Benabdallah Therese Kennelly-Okraku Mamadou Bodian Aaron King Jennifer Boylan Nicholas Knowlton Ben Burgen Chesney McOmber Leandra Clough Asmeret G. Mehari Amanda Edgell Stuart Mueller Dan Eizenga Anna Mwaba Timothy Fullman Collins R. Nunyonameh Ryan Good Sam Schramski Victoria Gorham Abiyot Seifu Cari Beth Head Donald Underwood Advisory Board Adélékè Adéèko Richard Marcus Ohio State University California State University, Long Beach Timothy Ajani Kelli Moore Fayetteville State University James Madison University Abubakar Alhassan Mantoa Rose Motinyane Bayero University University of Cape Town John W. Arthur James T. Murphy University of South Florida, St. Clark University Petersburg Lilian Temu Osaki Nanette Barkey University of Dar es Salaam Plan International USA Dianne White Oyler Susan Cooksey Fayetteville State University University of Florida Alex Rödlach Mark Davidheiser Creighton University Nova Southeastern University Jan Shetler Kristin Davis Goshen College International Food Policy Research Roos Willems Institute Catholic University of Leuven Parakh Hoon Peter VonDoepp Virginia Tech University of Vermont Andrew Lepp Kent State University African Studies Quarterly | Volume 14, Issue 3 | March 2014 http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq © University of Florida Board of Trustees, a public corporation of the State of Florida; permission is hereby granted for individuals to download articles for their own personal use. -

“Initiative on Capitalising on Endogenous Capacities for Conflict Prevention and Governance”

“Initiative on capitalising on endogenous capacities for conflict prevention and governance” Volume 2 Compilation of working documents Presented at the Initiative’s launching workshop SAH/D(2005)554 October 2005 1 2 “INITIATIVE ON CAPITALISING ON ENDOGENOUS CAPACITIES FOR CONFLICT PREVENTION AND GOVERNANCE” LAUNCHING WORKSHOP Hôtel Mariador Palace Conakry (Guinea) 9 – 11 March, 2005 Volume 2 Working documents October 2005 The working documents represent the views and analyses of the authors alone. It does not reflect the positions of the SWAC Secretariat or the OECD. "The translations do not replace the original texts. They have been prepared for the sole purpose of facilitating subsequent exchange of views between the English and French-speaking participants of the workshop. 3 4 Table of Contents SESSION 1. « A METHOD OF PREVENTION AND REGULATION IN WEST AFRICA: KINSHIP OF PLEASANTRY » .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 « Kinship of pleasantry: historical origin, preventative and regulatory role in West Africa » (Djibril Tamsir Niane) ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.2. The "Maat" kinship of pleasantry or the reign of the original model for social harmony (Babacar Sedikh Diouf) ........................................................................................................................... 17 SESSION 2. -

How a Lingua Franca Spreads

To appear in Ericka Albaugh & Kathryn M. de Luna, eds. Tracing Language Movement in Africa. Oxford University Press. 2017 How a lingua franca spreads Fiona Mc Laughlin 1 Introduction In terms of the relevance they have to people’s lives and the opportunities they afford them, African lingua francas are the most important languages spoken on the continent today. Their importance often gets lost in discussions of language in postcolonial Africa that offer a binary view of African vs. European languages, attributing economic and social advancement to mastery of the latter while failing to distinguish between the multiple roles that African (and European) languages might play. In this chapter I consider the ways in which one such lingua franca, Wolof, has become a vehicular language in Senegal and beyond, what it means to those who speak it, and how they value it. I will also consider how the former colonial and now official language, French, has contributed to the spread of Wolof, despite the efforts of the French colonial regime and its successor state to make it the language of the nation. The spread of a lingua franca means either an increase in its number of speakers, an increase in the contexts in which it is used, or both. Sociolinguists are interested in how such changes take place and what they entail for the linguistic ecology within which a lingua franca is spoken. Central to the notion of language change is the repertoire, the sum total of an individual’s linguistic resources and the ways in which s/he deploys them. -

Table of Contents

SENEGAL COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Walter J. Silva 1952-1954 General Services Clerk, Dakar Cecil S. Richardson 1956-1959 GSO/Consular/Admin Officer, Dakar Pearl Richardson 1956-1959 Spouse of GSO/Consular/Admin Officer, Dakar Arva C. Floyd 1960-1961 Office in charge of Senegal, Mali and Mauritania, African Bureau, Washington, DC Henry S. Villard 1960-1961 Ambassador, Senegal Stephen Low 1960-1963 Labor Officer / Political Officer, Dakar Helen C. (Sue) Low 1960-1963 Spouse of Labor Officer / Political Officer, Dakar Phillip M Kaiser 1961-1964 Ambassador, Senegal Hannah Greeley Kaiser 1961-1964 Spouse of Ambassador, Senegal Harriet Curry 1961-1964 Secretary to Ambassador Kaiser, Dakar Walter C. Carrington 1952 Delegate, Conference of the World Assembly of Youth, Dakar, Senegal 1965-1967 Peace Corps Director, Senegal Mercer Cook 1965-1966 Ambassador, Senegal and Gambia Philip C. Brown 1966-1967 Junior Officer Trainee, USIS, Dakar John A. McKesson, III 1966-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Dakar Irvin D. Coker 1967 USAID, Washington, DC Albert E. Fairchild 1967-1969 Central Complement Officer, Dakar L. Dean Brown 1967-1970 Ambassador, Senegal 1 Alan W. Lukens 1967-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Dakar Walter J. Sherwin 1969-1970 Program Officer, USAID, Dakar John L. Loughran 1970-1972 Chargé d’Affaires, Senegal Edward C. McBride 1970-1973 USIA, Cultural Attaché, Dakar David Shear 1970-1972 USAID Africa Bureau, Washington, DC Derek S. Singer 1972-1973 Office of Technical Cooperation, United Nations, Senegal Eric J. Boswell 1973-1975 General Services Officer, Dakar Frances Cook 1973-1975 Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Dakar Rudolph Aggrey 1973-1976 Ambassador, Senegal Allen C.