“Initiative on Capitalising on Endogenous Capacities for Conflict Prevention and Governance”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

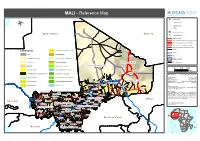

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: the Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary

Ali 1 Musical Imaginary, Identity and Representation: The Case of Gentleman the German Reggae Luminary A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction in Comparative Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Raghe Ali April 2013 The Ohio State University Project Advisors Professor Barry Shank, Department of Comparative Studies Professor Theresa Delgadillo, Department of Comparative Studies Ali 2 In 2003 a German reggae artist named Gentleman was scheduled to perform at the Jamworld Entertainment Center in the south eastern parish of St Catherine, Jamaica. The performance was held at the Sting Festival an annual reggae event that dates back some twenty years. Considered the world’s largest one day reggae festival, the event annually boasts an electric atmosphere full of star studded lineups and throngs of hardcore fans. The concert is also notorious for the aggressive DJ clashes1 and violent incidents that occur. The event was Gentleman’s debut performance before a Jamaican audience. Considered a relatively new artist, Gentleman was not the headlining act and was slotted to perform after a number of familiar artists who had already “hyped” the audience with popular dancehall2 reggae hits. When his turn came he performed a classical roots 3reggae song “Dem Gone” from his 2002 Journey to Jah album. Unhappy with his performance the crowd booed and jeered at him. He did not respond to the heckling and continued performing despite the audience vocal objections. Empty beer bottles and trash were thrown onstage. Finally, unable to withstand the wrath and hostility of the audience he left the stage. -

Sustainable Asset Valuation (Savi) of Senegal's Saloum Delta

Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi) of Senegal’s Saloum Delta An economic valuation of the contribution of the Saloum Delta to sustainable development, focussing on wetlands and mangroves SUMMARY OF RESULTS Andrea M. Bassi Liesbeth Casier Georg Pallaske Oshani Perera Ronja Bechauf © 2020 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org June 2020 Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi) of Senegal’s Saloum Delta © 2020 The International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Head Office is an independent think tank championing sustainable solutions 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 to 21st–century problems. Our mission is to promote human Winnipeg, Manitoba development and environmental sustainability. We do this through Canada R3B 0T4 research, analysis and knowledge products that support sound policymaking. Our big-picture view allows us to address the root causes of some of the greatest challenges facing our planet today: Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 ecological destruction, social exclusion, unfair laws and economic Website: www.iisd.org rules, a changing climate. IISD’s staff of over 120 people, plus over Twitter: @IISD_news 50 associates and 100 consultants, come from across the globe and from many disciplines. Our work affects lives in nearly 100 countries. Part scientist, part strategist—IISD delivers the knowledge to act. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Province of Manitoba and project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations, the private sector and individuals. -

ISSP Data Report – Report Data ISSP Current This Research

Das International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) erhebt jährlich Umfragedaten zu sozialwissenschaftlich relevanten Themen. Der vorliegende ISSP Data Report – Religious Attitudes and Religious Change beruht auf ISSP-Daten, die zu drei verschiedenen Zeitpunkten innerhalb von 17 Jahren in bis zu 42 Mitgliedsländern zu Einstellungen gegenüber Kirche und Religion im weitesten Sinne gesammelt wurden. Jedes Kapitel wurde von unterschiedlichen Autoren der ISSP-Gemeinschaft geschrieben und beleuchtet mit Hilfe der ISSP-Daten spezielle Aspekte religiöser Einstellungen und religiösen Wandels im internationalen Vergleich. In der Gesamtschau ergeben sich sowohl Einblicke in das religiöse Leben verschiedener Länder, als auch insbesondere Erkenntnisse zu den Einflussfaktoren religiösen Wandels innerhalb von fast zwei Dekaden. The annual survey of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) provides data on topics relevant in social research. This current ISSP Data Report – Religious Attitudes and Religious Change examines data collected at three different points over 17 years, from up to 42 ISSP member countries, covering various facets of respondents’ attitudes towards Church and Religion. Individual chapters were written by different members of the ISSP community thereby offering a cross-national, comparative perspective on particular aspects of religious attitudes and religious change via ISSP data. Overall, this report offers insights into the religious landscapes of various countries and in particular information about the factors influencing -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Download (3763Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/145151 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications APPENDIX A Containing Violence to What End? The Political Economy of Amnesty in Nigeria’s Oil-Rich Niger Delta (2009-2016) by Elvis Nana Kwasi Amoateng A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics and International Studies University of Warwick, Department of Politics and International Studies February 2020 Contents Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures ............................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................ 7 Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: ............................................................................................................... -

Civil Society Groups and the Role of Nonformal Adult Education Gary P

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Building Capacity for Decentralized Local Development in Chad: Civil Society Groups and the Role of Nonformal Adult Education Gary P. Liebert Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION BUILDING CAPACITY FOR DECENTRALIZED LOCAL DEVELOPMENT IN CHAD: CIVIL SOCIETY GROUPS AND THE ROLE OF NONFORMAL ADULT EDUCATION By GARY P. LIEBERT A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright 2005 Gary P. Liebert All rights reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Gary P. Liebert, defended on August 4, 2005. _______________________________ Peter B. Easton Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ John K. Mayo Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Emanuel Shargel Committee Member _______________________________ James H. Cobbe Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________ Joseph Beckham, Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many people who have helped me on this journey to complete my dissertation. I benefited greatly from the following people (all of whom live outside of Tallahassee) who provided assistance and advice as well as leads for research: Jim Bingen, Jim Alrutz, Richard Maclure, Thea Hilhorst, Trisha Long, Brook Johnson, Suzanne Gervais, Joshua Muskin and Jon Lauglo. I also want to thank the key informants of my research, who were invaluable to the research process. -

Darulfunun Ilahiyat, 30(1): 171–186

darulfunun ilahiyat, 30(1): 171–186 DOI: 10.26650/di.2019.30.1.0004 http://ilahiyatjournal.istanbul.edu.tr Submitted: 21.04.2018 Revision Requested: 27.06.2018 darulfunun ilahiyat Last Revision Received: 19.07.2018 Accepted: 17.01.2019 RESEARCH ARTICLE / ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESI Published Online: 20.05.2019 Redefining al-Mahdi: The Layennes of Senegal Thomas Douglas1 Abstract Limamou Laye (1844-1909) redefined the concept of the Mahdi with his proclamation. Though the concept of Mahdi has a history of variations across the Islamic world, Limamou Laye added a previously unknown characteristic: Mahdi as reincarnation of Muhammed. This article explores the history of the concept of the Mahdi focusing on the Sunni and Shi’a traditions. On the 24 May 1883, Libasse Thiaw (later known as Limamou Laye) proclaimed himself the Mahdi. His proclamation went on to say that he was the Prophet Muhammed returned to earth. Studying this event historically begs the question, why was this particular detail added to an honored Islamic messianic tradition? The answer lies in the history and geographical positioning of the Lebu, the ethnicity to which Libasse Thiaw belonged. I argue that three cultural influences helped shaped the Lebu expression of the Mahdi. The first influence was the Lebu traditional religious belief system. The second was Islam as expressed and practiced in the Senegambia. The third was the Christianity that the French brought with them to the area. Keywords Mahdi • Layennes • Senegal • Limamou Laye • Lebu Mehdi’yi Yeniden Tanımlamak: Senegalli Layeciler Öz Limamou Laye’nın (1844-1909) mehdilik iddiası ‘mehdi’ kavramının yeniden tanımlanmasına neden olmuştur. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

Fatick 2005 Corrigé

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES -------------------- AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- SERVICE REGIONAL DE FATICK SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE DE LA REGION DE FATICK EDITION 2005 Juin 2006 SOMMAIRE Pages AVANT - PROPOS 3 0. PRESENTATION 4 – 6 I. DEMOGRAPHIE 7 – 14 II. EDUCATION 15 – 19 III. SANTE 20 – 26 IV. AGRICULTURE 27 – 35 V. ELEVAGE 36 – 48 VI. PECHE 49 – 51 VII. EAUX ET FORETS 52 – 60 VIII. TOURISME 61 – 64 IX. TRANSPORT 65 - 67 X. HYDRAULIQUE 68 – 71 XI. ARTISANAT 72 – 74 2 AVANT - PROPOS Cette présente édition de la situation économique met à la disposition des utilisateurs des informations sur la plupart des activités socio-économiques de la région de Fatick. Elle fournit une base de données actualisées, riches et détaillées, accompagnées d’analyses. Un remerciement très sincère est adressé à l’ensemble de nos collaborateurs aux niveaux régional et départemental pour nous avoir facilité les travaux de collecte de statistiques, en répondant favorablement à la demande de données qui leur a été soumise. Nous demandons à nos chers lecteurs de bien vouloir nous envoyer leurs critiques et suggestions pour nous permettre d’améliorer nos productions futures. 3 I. PRESENTATION DE LA REGION 1. Aspects physiques et administratifs La région de Fatick, avec une superficie de 7535 km², est limitée au Nord et Nord - Est par les régions de Thiès, Diourbel et Louga, au Sud par la République de Gambie, à l’Est par la région de Kaolack et à l’Ouest par l’océan atlantique. Elle compte 3 départements, 10 arrondissements, 33 communautés rurales, 7 communes, 890 villages officiels et 971 hameaux.