The Return of Sanio Millet in Thee Sine : Rational Adaptation to Climate Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fatick 2005 Corrigé

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES -------------------- AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- SERVICE REGIONAL DE FATICK SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE DE LA REGION DE FATICK EDITION 2005 Juin 2006 SOMMAIRE Pages AVANT - PROPOS 3 0. PRESENTATION 4 – 6 I. DEMOGRAPHIE 7 – 14 II. EDUCATION 15 – 19 III. SANTE 20 – 26 IV. AGRICULTURE 27 – 35 V. ELEVAGE 36 – 48 VI. PECHE 49 – 51 VII. EAUX ET FORETS 52 – 60 VIII. TOURISME 61 – 64 IX. TRANSPORT 65 - 67 X. HYDRAULIQUE 68 – 71 XI. ARTISANAT 72 – 74 2 AVANT - PROPOS Cette présente édition de la situation économique met à la disposition des utilisateurs des informations sur la plupart des activités socio-économiques de la région de Fatick. Elle fournit une base de données actualisées, riches et détaillées, accompagnées d’analyses. Un remerciement très sincère est adressé à l’ensemble de nos collaborateurs aux niveaux régional et départemental pour nous avoir facilité les travaux de collecte de statistiques, en répondant favorablement à la demande de données qui leur a été soumise. Nous demandons à nos chers lecteurs de bien vouloir nous envoyer leurs critiques et suggestions pour nous permettre d’améliorer nos productions futures. 3 I. PRESENTATION DE LA REGION 1. Aspects physiques et administratifs La région de Fatick, avec une superficie de 7535 km², est limitée au Nord et Nord - Est par les régions de Thiès, Diourbel et Louga, au Sud par la République de Gambie, à l’Est par la région de Kaolack et à l’Ouest par l’océan atlantique. Elle compte 3 départements, 10 arrondissements, 33 communautés rurales, 7 communes, 890 villages officiels et 971 hameaux. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

Situation De La Saisie Des Données Covid-19 À La Date Du 17 Mars 2021

Février 2021 N°38 Le Bulletinde la DPRS Situation de la saisie des données Covid-19 à la date du 17 Mars 2021 Région District Saisie Saisies Reste à Région District Saisie Saisies Reste à Médicale Sanitaire Officielle Tracker saisir Médicale Sanitaire Officielle Tracker saisir Dhis2 Mars Dhis2 Mars Dakar Centre 5577 3315 2262 Kedougou 392 209 183 Dakar Nord 2630 2319 311 Dakar Ouest 5164 3911 1253 Salemata 29 1 28 Dakar Sud 4047 2614 1433 Saraya 102 45 57 Diamniadio 442 337 105 RM Kédougou Total 523 255 268 Guédiawaye 1262 938 324 Keur Massar 699 410 289 Kolda 300 4 296 Medina Yoro Mbao 992 935 57 7 2 5 RM Dakar Foulah Pikine 520 336 184 Vélingara 171 162 9 Rufisque 1079 866 213 RM Kolda Total 478 168 310 Sangalkam 323 291 32 Dahra 159 1 158 Yeumbeul 234 190 44 Darou 69 1 68 Total 22969 16462 6507 -Mousty Bambey 62 42 20 Kebemer 94 94 Diourbel 1282 168 1114 Keur Momar 13 2 11 Mbacké 88 137 0 Sarr Touba 1279 979 300 Koki 71 5 66 RM Louga RM Diourbel Total 2711 1326 1434 Linguere 106 3 103 Diakhao 7 1 6 Louga 460 353 107 Dioffior 6 5 1 Sakal 63 3 60 Fatick 278 233 45 Total 1035 368 667 Foundiougne 37 37 Kanel 34 30 4 Gossas 9 9 0 Matam 306 263 43 Niakhar 10 10 Ranerou 9 1 8 RM Fatick Passy 14 21 0 Thilogne 26 26 0 RM Matam Sokone 314 22 292 Total 375 320 55 Total 675 291 391 Dagana 39 12 27 Birkelane 27 32 0 Pete 30 30 0 Kaffrine 96 54 42 Podor 83 71 12 Koungheul 24 4 20 Richard-Toll 375 375 0 Malem Saint-Louis 873 499 374 8 3 5 Hodar RM Saint-Louis Total 1400 987 413 RM Kaffrine Total 155 93 67 Bounkiling 28 18 10 Guinguineo 88 2 86 Kaolack 1374 220 1154 Goudomp 4 4 Ndoffane 61 8 53 Sedhiou 149 129 20 Nioro 90 1 89 RM Sedhiou RM Kaolack Total 1613 231 1382 Total 181 147 34 Région District Saisie Saisies Reste à Pour le mois de Mars 2021, le gap s’est accentué Médicale Sanitaire Officielle Tracker saisir dans plusieurs régions médicales plus particulière- Dhis2 Mars Bakel 28 2 26 ment à Dakar et Thies. -

Les Peuplements De Poissons Des Milieux Estuariens De L'afrique De L

Thèses et documents microfiches Les peuplements de poissons des milieux estuariens de l’Afrique de l’Ouest : L’exemple de l’estuaire hyperhalin du Sine-Saloum. THESE présentée à I’U-NIVERSITE DE MONTPELLIER II pour l’obtention du Diplôme de DOCTORAT SPECIALITE : Biologie des populations et écologie FORMATION DOCTORALE : Biologie de l’évolution et écologie ECOLE DOCTORALE : Biologie des systèmes intégrés Papa Samba DIOUF Soutenue le 29 avril 1996 devant le Jury composé de MM - -_ G. LASSERRE Professeur, UM II, Montpellier Directeur de Thèse J.-J. ALBARET Directeur de Recherche, ORSTOM, Montpellier Directeur de Thèse . C. LEVEQUE Directeur de Recherche, ORSTOM, Paris Rapporteur R. GALZIN Professeur, EPHE, Perpignan Rapporteur J.-L. BOUCHEREAU, Maître de Conférences, UM II, Montpellier Examinateur no156 3 microfiches Thèses et documents microfichés Orstom, l’institut frayais de recherche scientifique pour le développement en coopération La loi du ler juillet 1992 (code de la propriété intellectuelle, première partie) n’autorisant, aux termes des alinéas 2 et 3 de l’article L. 122-5, d’une part, que les « copies ou reproductions stricte- ment réservées à l’usage du copiste et non destinées a une utilisation collective » et, d’autre part, que les analyses et les courtes citations dans le but d’exemple et d’illustration, « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » (alinéa ler de l’article L. 122-4). Cette représentation ou reproduction, par quelque procédé que ce soit, constituerait donc une contrefaçon passible des peines prévues au titre III de la loi précitée. -

Report on Language Mapping in the Regions of Fatick, Kaffrine and Kaolack Lecture Pour Tous

REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK LECTURE POUR TOUS Submitted: November 15, 2017 Revised: February 14, 2018 Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Activity Start and End Date: October 26, 2016 to July 10, 2021 Total Award Amount: $71,097,573.00 Contract Officer’s Representative: Kadiatou Cisse Abbassi Submitted by: Chemonics International Sacre Coeur Pyrotechnie Lot No. 73, Cite Keur Gorgui Tel: 221 78585 66 51 Email: [email protected] Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 1 REPORT ON LANGUAGE MAPPING IN THE REGIONS OF FATICK, KAFFRINE AND KAOLACK Contracted under AID-OAA-I-14-00055/AID-685-TO-16-00003 Lecture Pour Tous DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publicapublicationtion do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States AgenAgencycy for International Development or the United States Government. Lecture Pour Tous - Report on Language Mapping – February 2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 2. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 12 3. STUDY OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. Context of the study ............................................................................................................. 14 3.2. -

F a T I C K 2 0

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi ------------------ F MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN ------------------ AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE A ------------------ Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Fatick T I C K 2 SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET 0 SOCIALE REGIONALE 1 2012 Juin 2015 2 COMITE DE DIRECTION Directeur Général Aboubacar Sédikh BEYE Directeur Général Adjoint Mamadou Falou MBENGUE Directeur des Statistiques Démographiques et Sociales Cheikh Tidiane NDIAYE Directeur des Statistiques Economiques et de la Mbaye FAYE Comptabilité Nationale Directeur du Management de l’Information Statistique Mamadou NIANG Conseiller à l’Action Régionale Mamadou DIENG COMITE DE REDACTION Chef du Service Régional Issa DIOP Adjoint du Chef du Service Régional Djiby SENE Chef du Service Régional Par Intérim Moustapha DIENG COMITE DE VALIDATION Séckène SENE, Abdoulaye TALL, Mamadou DIENG, Mamadou BAH, Oumar DIOP, El hadji Malick GUEYE, Alain François DIATTA, Saliou MBENGUE, Alpha WADE, Thiayédia NDIAYE, Amadou Fall DIOUF, Adjibou Oppa BARRY, Atoumane FALL, Jean Rodrigue MALOU, Bintou Diack LY. AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE Rocade Fann Bel-air Cerf-volant - Dakar. B.P. 116 Dakar R.P. - Sénégal Téléphone (221) 33 869 21 39 / 33 869 21 60 - Fax (221) 33 824 36 15 Site web : www.ansd.sn ; Email: [email protected] Distribution : Division de la Documentation, de la Diffusion et des Relations avec les Usagers SERVICE REGIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE DE FATICK Tél : 33 949 10 56 ANSD/SRSD Fatick : Situation Economique et Sociale régionale ‐ 2012 ii CHAPITRE VII - HYDRAULIQUE INTRODUCTION Le sous-secteur de l’hydraulique constitue un élément stratégique du développement économique et social. -

12263638.Pdf

RÉPUBLIQUE DU SÉNÉGAL MINISTÈRE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT ET DU DÉVELOPPEMENT DURABLE AGENCE NATIONALE DES ECOVILLAGES PROJET D’APPUI VISANT À PROPULSER LE DÉVELOPPEMENT RURAL EN ASSURANT L’HARMONISATION DE L’ÉCOLOGIE ET L’ÉCONOMIE (PROMOTION DES ECOVILLAGES) Rapport final AOUT 2016 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) Earth and Human Corporation Carte : Zone d’intervention du Projet Carte : Zone d’intervention du Projet i Photos des activités Atelier de lancement (décembre 2012) Réunion du Comité de Pilotage (juillet 2013) Plateforme centrale (août 2013) Plateforme régionale (août 2013, Louga) Panneaux solaires installés à la zone de Equipement Goutte à Goutte installé à la Niaye (AP1) zone de Niaye (AP2) Réunion du cadre de concertation des Biodigesteur (AP2, AP4) apiculteurs de la région de Fatick (AP3) ii Fabrication de briquette de charbon Visite d’échanges entres les villages provenant de tiges de typha (AP5) bénéficiaires (mai 2015, Thiès) Sommet Mondial des Ecovillages Visite des réalisations du projet par les (décembre 2014) Parlementaires (octobre 2015, Région de Thiès) Formation au Japon (février 2014, 3ème conférence sur la Réduction des Préfecture de Kanagawa, etc.) Risques de Catastrophes (mars 2015, Sendai) Sensibilisation des collectivités locales Présentation du projet à la COP 21 pour la planification d’activités de promotion (novembre, décembre 2015, Paris) des écovillages (mars 2016) iii Sigles et Abréviation Abréviation Signification ACDI Agence Canadienne de Développement International ACEP Agence de Crédit -

Repertoire Structures Privees.Pdf

REPERTOIRE STRUCTURES PRIVEES EN SANTE LOCALISATION Nom de la structure TYPE Adresse Fatick FATICK DEPOT DE DIAOULE Dépôt COMMUNE DE DIAOULE Kolda VELINGARA DEPOT PHARMACIE BISSABOR Dépôt BALLANA PAKOUR PRES DU NOUVEAU MARCHE Kolda VELINGARA DEPOT BISSABOR /WASSADOU Dépôt CENTRE EN FACE SONADIS Ziguinchor ZIGUINCHOR DEPOT ADJAMAAT Dépôt NIAGUIS PRES DE LA PHARMACIE Kédougou SALEMATA DEPOT SALEMATA Dépôt KOULOUBA SALEMATA Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE DE L'EMMANUEL Pharmacie GRAND DAKAR A COTE GARAGE CASAMANCE OU ECOLE XALIMA Ziguinchor ZIGUINCHOR PHARMACIE NEMA Pharmacie GRAND DAKAR PRES DU MARCHE NGUELAW Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE NOUROU DAREYNI Pharmacie RUE 1 CASTOR DERKHELE N 25 Kédougou KEDOUGOU PHARMACIE YA SALAM Pharmacie MOSQUE KEDOUGOU PRES DU MARCHE CENTRAL Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE DU BOULEVARD Pharmacie RUE 22 X 45 MEDINA QUARTIER DAGOUANE PIKINE TALLY BOUMACK N545_547 PRES DE Dakar PIKINE PHARMACIE PRINCIPALE Pharmacie LA POLICE Dakar GUEDIAWAYE PHARMACIE DABAKH MALICK Pharmacie DAROU RAKHMANE N 1981 GUEDIAWAYE SOR SAINT LOUIS MARCHE TENDJIGUENE AVENUE GENERALE DE Saint-Louis SAINT-LOUIS PHARMACIE MAME MADIA Pharmacie GAULLE BP 390 Dakar DAKAR CENTRE PHARMACIE NDOSS Pharmacie AVENUE CHEIKH ANTA DIOP RUE 41 DAKAR FANN RANDOULENE NORD AVENUE EL HADJI MALICK SY PRES PLACE DE Thies THIES PHARMACIE SERIGNE SALIOU MBACKE Pharmacie FRANCE Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE LAT DIOR Pharmacie ALLES PAPE GUEYE FALL Dakar DAKAR SUD PHARMACIE GAMBETTA Pharmacie 114 LAMINE GUEYE PLATEAU PRES DE LOFNAC Louga KEBEMER PHARMACIE DE LA PAIX Pharmacie -

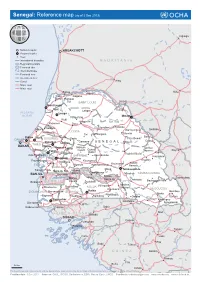

M a U R I T a N I a G U I N E a M a L I Guinea-Bissau Gambia

Senegal: Reference map (as of 3 Dec 2013) Tidjikdja National capital NOUAKCHOTT Regional capital Town International boundary MAURITANIA Regional boundary Perennial lake Intermittent lake Perennial river Intermittent river Canal Aleg Major road Minor road Sénégal Rosso Kiffa Podor Ross Dagana Béthio Richard Toll SAINT LOUIS Kaédi Saint Louis Mpal Labgar Thilogne ATLANTIC Louga OCEAN Matam Yang-Yang Koki Linguère MATAM Kébémèr Dara Ndande Yonoféré Ranérou Mboro Diamounguél Sélibaby Mékhé LOUGA Tiel Vélingara Mamâri Bakel Pikine Thies Touba DAKAR DIOURBEL Sadio Fété Bowé Gassane Gabou Sé Diourbel SENEGAL Mboun négal THIÈS Mbacké DAKAR Niakhar Gossas Mbar Ndioum Sintiou Mbour Guènt Guènt Tapsirou Kayes Fatick Paté Guinguinéo Toubéré Bafal Kidira Joal-Fadhiouth KAFFRINE Lour-Escale Koussane Kaolack Kaffrine Goudiry Foundiougne Ndoffane Koungheul Sokone Koussanar Kotiari FATICK Nganda Koumpentoum Naoude MALI KAOLACK Gambi Maka Tambacounda Karang Poste Nioro du Rip Médina a Sabakh Georgetown TAMBACOUNDA BANJUL Kerewan Missirah Basse Mansa Pata Saïnsoubou Santa Su Dialacoto Boutougou Fara Brikama GAMBIA Konko Soulabali Vélingara Medina Diouloulou Bounkiling KOLDA Gounas Kounkané KÉDOUGOU ZIGUINCHOR Marsassoum SÉDHIOU Kolda Bembou Wassadou Mako Bignona Sédhiou Salikénié Dalaba Saraya Ziguinchor Tiankoye Kédougou Koundara Fongolembi Diembéreng Farim Kabrousse Cacheu Gabú a b Mali GUINEA-BISSAU ê Bafadá G BISSAU Gaoual Fulacunda ia b Bolama m G a Tongué a Catió Labé g n i f a Pita B Boké Telimele GUINEA Dalaba Mamou Fria Boffa 50 Km Kindia The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 3 Dec 2013 Sources: GAUL, ISCGM, Bartholomew, ESRI, Natural Earth, UNCS Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int. -

Letter Post Compendium Senegal

Letter Post Compendium Senegal Currency : FRANCS CFA Basic services Mail classification system (Conv., art. 13.3; Regs., art. RL 120) 1 Based on speed of treatment of items (Regs., art. RL 120.2): Yes 1.1 Priority and non-priority items may weigh up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. RL 122.1). Whether admitted Yes or not: 2 Based on contents of items (Regs., art. RL 122.2): Yes 2.1 Letters and small packets weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. RL 122.2.1). Whether admitted or No not (dispatch and receipt): 2.2 Printed papers weighing up to 5 kilogrammes (Regs., art. RL 122.2.2). Whether admitted or not for No dispatch (obligatory for receipt): 3 Classification of post items to the letters according to their size (Conv., art. 14; Regs., art. RL 121.2) No Optional supplementary services 4 Insured items (Conv., art. 15.2; Regs., art. RL 138.1) 4.1 Whether admitted or not (dispatch and receipt): Yes 4.2 Whether admitted or not (receipt only): No 4.3 Declaration of value. Maximum sum 4.3.1 surface routes: SDR 4.3.2 air routes: 600 SDR 4.3.3 Labels (RL 138.6.3 et 138.6.4) . CN 06 label or two labels (CN 04 and pink "Valeur déclarée" (insured) CN 06 label label) used: 4.4 Offices participating in the service: All offices 4.5 Services used: 4.5.1 air services (IATA airline code): 4.5.2 sea services (names of shipping companies): 4.6 Office of exchange to which a duplicate CN 24 formal report must be sent (Regs., art. -

Analysing Normative Influences on the Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Among 0–14 Years Old Girls in Senegal: A

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Analysing Normative Influences on the Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting among 0–14 Years Old Girls in Senegal: A Spatial Bayesian Hierarchical Regression Approach Ngianga-Bakwin Kandala 1,2,*, Chibuzor Christopher Nnanatu 3 , Glory Atilola 3 , Paul Komba 3, Lubanzadio Mavatikua 3, Zhuzhi Moore 4 and Dennis Matanda 5 1 Division of Health Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK 2 Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa 3 Department of Mathematics, Physics & Electrical Engineering (MPEE), Northumbria University, Newcastle NE1 8ST, UK; [email protected] (C.C.N.); [email protected] (G.A.); [email protected] (P.K.); [email protected] (L.M.) 4 Independent Consultant, Vienna, VA 22182, USA; [email protected] 5 Population Council, Avenue 5, 3rd Floor, Rose Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background: Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is a harmful traditional practice affecting the health and rights of women and girls. This has raised global attention on the imple- Citation: Kandala, N.-B.; Nnanatu, mentation of strategies to eliminate the practice in conformity with the Sustainable Development C.C.; Atilola, G.; Komba, P.; Goals (SDGs). A recent study on the trends of FGM/C among Senegalese women (aged 15–49) Mavatikua, L.; Moore, Z.; Matanda, D. which examined how individual- and community-level factors affected the practice, found significant Analysing Normative Influences on regional variations in the practice. -

Niakhar Dss Senegal

NIAKHAR DSS SENEGAL INSTITUT DE RECHERCHE POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT IRD SenegalSenegal S E N E G A L NiakharNiakhar DSSDSS SiteSite FatickFatick RegionRegion Gambia Fatick region 00 12.512.5 2525 00 100100 200200 KilometersKilometers Kilometers LOCATION OF NIAKHAR DSS SITE, SENEGAL: Monitored Population 29,000 Valérie Delaunay, Adama Marra, Pierre Levi, and Jean-François Etard Chapter C 20 Page 1 1. NIAKHAR DSS SITE DESCRIPTION 1.1 Physical Geography of the Niakhar DSS Area The study zone of Niakhar is located in Senegal, at N 14º30' and W 16º30. It is located in the Department of Fatick, Region of Fatick (Sine-Saloum), 135 km East of Dakar. The Niakhar study zone is about 15 km long by 15 km wide and covers 230 square km. The climate is continental sudan-sahelian, with temperatures ranging from 24°C in December-January to 30°C in May-June. For thirty years the region has suffered from drought. Rainfall decreased from 808 mm per year for the period 1921-67 to 520 mm for 1968-87 and to 463 mm for 1988-98. 1.2 Population Characteristics of the Niakhar DSS Area From 1962 to 1966, 65 villages were surveyed annually. The study zone was then reduced to eight villages until 1983, when it was extended to include 22 villages, forming the current study zone, comprising 30 villages. Hence, eight villages have been under demographic monitoring for 37 years and 30 villages for 16 years. The Niakhar area has a population of 30,215 inhabitants as of 1st January 2000, and a high population density with about 131 inhabitants per km².