ECFG-Senegal-2020R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report1

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons TTCSP Global Go To Think aT nk Index Reports Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) 1-2019 2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report James G. McGann University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks Part of the International and Area Studies Commons McGann, James G., "2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report" (2019). TTCSP Global Go To Think Tank Index Reports. 16. https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/16 2019 Copyright: All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the University of Pennsylvania, Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program. All requests, questions and comments should be sent to: James G. McGann, Ph.D. Senior Lecturer, International Studies Director, Think aT nks and Civil Societies Program The Lauder Institute University of Pennsylvania Email: [email protected] This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/16 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2018 Global Go To Think aT nk Index Report Abstract The Thinka T nks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) of the Lauder Institute at the University of Pennsylvania conducts research on the role policy institutes play in governments and civil societies around the world. Often referred to as the “think tanks’ think tank,” TTCSP examines the evolving role and character of public policy research organizations. -

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

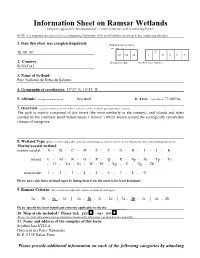

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

Fatick 2005 Corrigé

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES -------------------- AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ----------------- SERVICE REGIONAL DE FATICK SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE DE LA REGION DE FATICK EDITION 2005 Juin 2006 SOMMAIRE Pages AVANT - PROPOS 3 0. PRESENTATION 4 – 6 I. DEMOGRAPHIE 7 – 14 II. EDUCATION 15 – 19 III. SANTE 20 – 26 IV. AGRICULTURE 27 – 35 V. ELEVAGE 36 – 48 VI. PECHE 49 – 51 VII. EAUX ET FORETS 52 – 60 VIII. TOURISME 61 – 64 IX. TRANSPORT 65 - 67 X. HYDRAULIQUE 68 – 71 XI. ARTISANAT 72 – 74 2 AVANT - PROPOS Cette présente édition de la situation économique met à la disposition des utilisateurs des informations sur la plupart des activités socio-économiques de la région de Fatick. Elle fournit une base de données actualisées, riches et détaillées, accompagnées d’analyses. Un remerciement très sincère est adressé à l’ensemble de nos collaborateurs aux niveaux régional et départemental pour nous avoir facilité les travaux de collecte de statistiques, en répondant favorablement à la demande de données qui leur a été soumise. Nous demandons à nos chers lecteurs de bien vouloir nous envoyer leurs critiques et suggestions pour nous permettre d’améliorer nos productions futures. 3 I. PRESENTATION DE LA REGION 1. Aspects physiques et administratifs La région de Fatick, avec une superficie de 7535 km², est limitée au Nord et Nord - Est par les régions de Thiès, Diourbel et Louga, au Sud par la République de Gambie, à l’Est par la région de Kaolack et à l’Ouest par l’océan atlantique. Elle compte 3 départements, 10 arrondissements, 33 communautés rurales, 7 communes, 890 villages officiels et 971 hameaux. -

The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena

www.ssoar.info The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness Onoma, Ato Kwamena Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Onoma, A. K. (2018). The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness. Africa Spectrum, 53(3), 65-88. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-ND Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-ND Licence Keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NoDerivatives). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/deed.de Africa Spectrum Onoma, Ato Kwamena (2018), The Grave Preferences of Mourides in Senegal: Migration, Belonging, and Rootedness, in: Africa Spectrum, 53, 3, 65–88. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11588 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs, in co-operation with the Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Freiburg, and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. -

The Faith Sector and HIV/AIDS in Botswana

The Faith Sector and HIV/AIDS in Botswana The Faith Sector and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: Responses and Challenges Edited by Lovemore Togarasei with Sana K. Mmolai and Fidelis Nkomazana The Faith Sector and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: Responses and Challenges, Edited by Lovemore Togarasei with Sana K. Mmolai and Fidelis Nkomazana This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Lovemore Togarasei with Sana K. Mmolai and Fidelis Nkomazana and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2694-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2694-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................... vii List of Abbreviations.................................................................................. ix Introduction ................................................................................................ xi Lovemore Togarasei Part I: Background Chapter One................................................................................................. 2 The Botswana Religious Landscape Fidelis Nkomazana Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

And the Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects

VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF CENTRAL COASTAL SENEGAL (SALOUM) AND THE GAMBIA MARINE COAST AND ESTUARY TO CLIMATE CHANGE INDUCED EFFECTS Consolidated Report GAMBIA- SENEGAL SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES PROJECT (USAID/BA NAFAA) April 2012 Banjul, The Gambia This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website at http://www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA. Tel: 401) 874-6224; Fax: 401) 789-4670; Email: [email protected] Citation: Dia Ibrahima, M. (2012). Vulnerability Assessment of Central Coast Senegal (Saloum) and The Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects. Coastal Resources Center and WWF-WAMPO, University of Rhode Island, pp. 40 Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cooperative Agreement # 624-A-00-09-00033-00. ii Abbreviations CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CIA Central Intelligence Agency CMS Convention on Migratory Species, CSE Centre de Suivi Ecologique DoFish Department of Fisheries DPWM Department Of Parks and Wildlife Management EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone ETP Evapotranspiration FAO United Nations Organization for Food and Agriculture GIS Geographic Information System ICAM II Integrated Coastal and marine Biodiversity management Project IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IUCN International Union for the Conservation of nature NAPA National Adaptation Program of Action NASCOM National Association for Sole Fisheries Co-Management Committee NGO Non-Governmental Organization PA Protected Area PRA Participatory Rapid Appraisal SUCCESS USAID/URI Cooperative Agreement on Sustainable Coastal Communities and Ecosystems UNFCCC Convention on Climate Change URI University of Rhode Island USAID U.S. -

Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3

Aram Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3 SOMALIA'S JUDEAO-CHRISTIAN HERITAGE: A PRELIMINARY SURVEY Ben I. Aram* INTRODUCTION The history of Christianity in Somalia is considered to be very brief and as such receives only cursory mention in many of the books surveying this subject for Africa. Furthermore, the story is often assumed to have begun just over a century ago, with the advent of modem Western mission activity. However, evidence from three directions sheds light on the pre Islamic Judeao-Christian influence: written records, archaeological data and vestiges of Judeao-Christian symbolism still extant within both traditional 1 Somali culture and closely related ethnic groups • Together such data indicates that both Judaism and Christianity preceded Islam to the lowland Horn of Africa In the introduction to his article on Nubian Christianity, Bowers (1985:3-4) bemoans the frequently held misconception that Christianity only came recently to Africa, exported from the West. He notes that this mistake is even made by some Christian scholars. He concludes: "The subtle impact of such an assumption within African Christianity must not be underestimated. Indeed it is vital to African Christian self-understanding to recognize that the Christian presence in Africa is almost as old as Christianity itself, that Christianity has been an integral feature of the continent's life for nearly two thousand years." *Ben I. Aram is the author's pen name. The author has been in ministry among Somalis since 1982, in somalia itself, and in Kenya and Ethiopia. 1 These are part of both the Lowland and Highland Eastern Cushitic language clusters such as Oromo, Afar, Hadiya, Sidamo, Kambata, Konso and Rendille. -

The Return of Sanio Millet in Thee Sine : Rational Adaptation to Climate Evolution

Escape-P4-GB.qxp_Escape-MEP 21/10/2017 08:54 Page351 The return of Sanio millet in the Sine Chapter 18 The return of Sanio millet in the Sine Rational adaptation to climate evolution Bertrand MULLER, Richard LALOU, Patrice KOUAKOU, Mame Arame SOUMARÉ, Jérémy BOURGOIN, Séraphin DORÉGO, Bassirou SINE Introduction Sanio millet1 has reappeared in villages in the Sine, between Bambey, Diourbel and Fatick, since the mid-2000s. However, this long cycle millet had disappeared from farms in the northern half of Senegal in the 1970s because of the sudden decrease in rainfall. It was still present further south in the wetter regions of Saloum and beyond as far as the Casamance. As rainfall depths increased from the mid-1990s everywhere in Senegal (SALACK et al., 2011), we put forward the hypothesis that this return could form a robust agronomic ‘marker’ of recent pluviometric evolution in central-western Senegal and show the ability of farmers to adapt rapidly and independently—i.e. without the support of agronomic engineering2—to changes in their environment. However, although the climatic opportunity provided by the return of rainfall seems to be a necessary condition for the production of Sanio, it may not be enough to explain why Sanio is not chosen by all farmers, as it was in the past. Since the climate change theme has become an ordinary paradigm of science and public action, it has become commonplace to recognise that agriculture in Africa lacks financial and technological resources for adapting to climatic and environmental events (ADGER, 2006a and 2006b). But individual or collective adaptation is not new for African 1. -

A Commentary on the September 2011 Eritrea Operational Guidance Note

THIS DOCUMENT SHOULD BE USED AS A TOOL FOR IDENTIFYING RELEVANT COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION. IT SHOULD NOT BE SUBMITTED AS EVIDENCE TO THE UK BORDER AGENCY, THE TRIBUNAL OR OTHER DECISION MAKERS IN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS OR APPEALS. November 2011 A commentary on the September 2011 Eritrea Operational Guidance Note This commentary identifies what the ‘Still Human Still Here’ coalition considers to be the main inconsistencies and omissions between the currently available country of origin information (COI) and case law on Eritrea and the conclusions reached in the September 2011 Eritrea Operational Guidance Note (OGN), issued by the UK Border Agency. Where we believe inconsistencies have been identified, the relevant section of the OGN is highlighted in blue. An index of full sources of the COI referred to in this commentary is also provided at the end of the document. This commentary is a guide for legal practitioners and decision-makers in respect of the relevant COI, by reference to the sections of the Operational Guidance Note on Eritrea issued in September 2011. To access the complete OGN on Eritrea go to: http://www.bia.homeoffice.gov.uk/sitecontent/documents/policyandlaw/countryspecificasylum policyogns/ The document should be used as a tool to help to identify relevant COI and the COI referred to can be considered by decision makers in assessing asylum applications and appeals. This document should not be submitted as evidence to the UK Border Agency, the Tribunal or other decision makers in asylum applications or appeals. However, legal representatives are welcome to submit the COI referred to in this document to decision makers (including judges) to help in the accurate determination of an asylum claim or appeal.