NOTE 160P.; Title in English and French, but Text All in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Cultural Policy 2012 (Draft)

NATIONAL CULTURAL POLICY MONTSERRAT (DRAFT) TABLE OF CONTENTS Pg Executive Summary 1 Philosophical Statement 1 2 Methodology 1 3 Background 2 4 Definition of Culture 4 5 Mapping the Cultural Landscape 5 6 The Cultural Backdrop 6 7 Proposed Policy Positions of the Government of Montserrat 16 8 Aims of the Policy 17 9 Self Worth and National Pride 18 10 The Arts 21 11 Folkways 24 12 Masquerades 27 13 Heritage 29 14 Education 32 15 Tourism 35 16 Economic Development 38 17 Media and Technology 41 18 Infrastructure 44 19 Implementation 47 Appendix 1 Groups & Persons Consulted Appendix 2 Consulting Instruments Select Biography EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary presents a brief philosophical statement, the policy positions of the government and the aims of the policy. It defines culture, outlines the areas of national life considered in the policy and provides a selection of the action to be taken. The policy document emphasizes the importance of the development of a sense of self-worth and national pride, the role of folkways in defining a Montserratian identity and the role of training, research and documentation in cultural development and preservation. Particular emphasis is placed on culture as a means of broadening the frame of economic activity. The co modification of aspects of culture brooks of no debate; it is inevitable in these challenging economic times. The policy is presented against a backdrop of the Montserrat cultural landscape. Philosophical Statement Montserrat’s culture is rooted in its history with all its trials and triumphs. Culture is not only dynamic and subject to influences and changes over time, but it is also dialectical, meaning that while it springs from history and development, culture also impacts and informs development . -

CARNIVAL and OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, USA and Britain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE CARNIVAL AND OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, U.S.A. and Britain: a selected bibliographical index by John Cowley First published as: Bibliographies in Ethnic Relations No. 10, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, September 1991, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL John Cowley has published many articles on blues and black music. He produced the Flyright- Matchbox series of LPs and is a contributor to the Blackwell Guide To Blues Records, and Black Music In Britain (both edited by Paul Oliver). He has produced two LPs of black music recorded in Britain in the 1950s, issued by New Cross Records. More recently, with Dick Spottswood, he has compiled and produced two LPs devoted to early recordings of Trinidad Carnival music, issued by Matchbox Records. His ‗West Indian Gramophone Records in Britain: 1927-1950‘ was published by the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations. ‗Music and Migration,‘ his doctorate thesis at the University of Warwick, explores aspects of black music in the English-speaking Caribbean before the Independence of Jamaica and Trinidad. (This selected bibliographical index was compiled originally as an Appendix to the thesis.) Contents Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 7 How to use this index 8 Bibliographical index 9 Bibliography 24 Introduction The study of the place of festivals in the black diaspora to the New World has received increased attention in recent years. Investigations range from comparative studies to discussions of one particular festival at one particular location. It is generally assumed that there are links between some, if not all, of these events. -

An Ethnography of African Diasporic Affiliation and Disaffiliation in Carriacou: How Anglo-Caribbean Preadolescent Girls Express Attachments to Africa

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses August 2015 An Ethnography of African Diasporic Affiliation and Disaffiliation in Carriacou: How Anglo-Caribbean Preadolescent Girls Express Attachments to Africa Valerie Joseph University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Joseph, Valerie, "An Ethnography of African Diasporic Affiliation and Disaffiliation in Carriacou: How Anglo-Caribbean Preadolescent Girls Express Attachments to Africa" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 370. https://doi.org/10.7275/6962219.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/370 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF AFRICAN DIASPORIC AFFILIATION AND DISAFFILIATION IN CARRIACOU: HOW ANGLO-CARIBBEAN PREADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPRESS ATTACHMENTS TO AFRICA A Dissertation Presented By Valerie Joseph Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Department of Anthropology © Copyright by Valerie Joseph 2015 All Rights Reserved AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

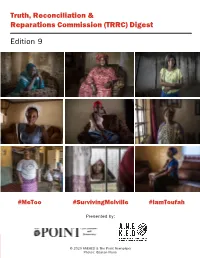

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 9

Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) Digest Edition 9 #MeToo #SurvivingMelville #IamToufah Presented by: © 2020 ANEKED & The Point Newspaper 1| Photos: ©Jason Florio The Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) is mandated to investigate and establish an impartial historical record of the nature, causes and extent of violations and abuses of human rights committed during the period of July 1994 to January 2017 and to consider the granting of reparations to victims and for connected matters. It started public hearings on 7th January 2019 and will proceed in chronological order, examining the most serious human rights violations that occurred from 1994 to 2017 during the rule of former President Yahya Jammeh. While the testimonies are widely reported in the press and commented on social media, triggering vivid discussions and questions regarding the current transitional process in the country, a summary of each thematic focus/event and its findings is missing. The TRRC Digests seek to widen the circle of stakeholders in the transitional justice process in The Gambia by providing Gambians and interested international actors, with a constructive recount of each session, presenting the witnesses and listing the names of the persons mentioned in relation to human rights violations and – as the case may be – their current position within State, regional or international institutions. Furthermore, the Digests endeavour to highlight trends and patterns of human rights violations and abuses that occurred and as recounted during the TRRC hearings. In doing so, the TRRC Digests provide a necessary record of information and evidence uncovered – and may serve as “checks and balances” at the end of the TRRC’s work. -

Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 6-4-2018 Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, Vivian, "Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4744. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLVING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF DEBUSSY’S PIANO PRELUDES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The Department of Music and Dramatic Arts by Vivian Buchanan B.M., New England Conservatory of Music, 2016 August 2018 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..iii Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………… 1 2. The Welte-Mignon…………………………………………………………. 7 3. The French Harpsichord Tradition………………………………………….18 4. Debussy’s Piano Rolls……………………………………………………....35 5. The Early Debussystes……………………………………………………...52 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………...63 Selected Discography………………………………………………………………..66 Vita…………………………………………………………………………………..67 ii Abstract Between 1910 and 1912 Claude Debussy recorded twelve of his solo piano works for the player piano company Welte-Mignon. Although Debussy frequently instructed his students to play his music exactly as written, his own recordings are rife with artistic liberties and interpretive freedom. -

Wavelength (September 1986)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 9-1986 Wavelength (September 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (September 1986) 71 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/62 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NS SIC MAGA u........s......... ..AID lteniiH .... ., • ' lw•~.MI-- "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans." -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features The Party ... .... .. .. ... 21 The Faith . .... .. ....... 23 The Saints . .... .... .. 24 Departments September News ... ... .. 4 Latin ... ... .. ..... .. 8 Chomp Report ...... .. .. 10 Caribbean . .. .. ......... 12 Rock ........ ... ........ 14 Comedy ... ... .... .. ... 16 U.S. Indies .. .. ... .. ... 18 September Listings ... ... 29 Classifieds ..... ..... 33 Last Page . .. .. .... .... 34 Cover Art by Bunny MaHhews A1mlbzrot NetWCSfk Pubaidwr ~ N.. un~.,~n S ~·ou F:ditor. Cnnn~ /..c;rn.ih Atk 1 n~ Assonat• FAI1lor. (it.:n..: S4.at.&mU/It) Art Dindor. Thom~... Oul.an Ad,mL-Jn •. Fht.ah.:th hlf1l.J•~ - 1>1.:.tn.a N.M.l~'-' COft· tributon, Sl(\\.' Armf,ru,tcr. St (M.."tlfl!C Hry.&n. 0..-t> C.n.Jh4:llll, R1d. Culcnun. Carul Gn1ad) . (iu'U GUl'uuo('. Lynn H.arty. P.-t Jully. J.mlC' l.k:n, Bunny M .anhc~'· M. 11.k Oltvter. H.1mmnnd ~·,teL IAlm: Sll'l"t:l. -

DAKAR, SENEGAL Onboard: 1800 Monday, October 24

Arrive: 0800 Friday, October 21 DAKAR, SENEGAL Onboard: 1800 Monday, October 24 Brief Overview: French-speaking Dakar, Senegal is the western-most city in all of Africa. As the capital and largest city in Senegal, Dakar is located on the Cape Verde peninsula on the Atlantic. Dakar has maintained remnants of its French colonial past, and has much to offer both geographically and culturally. Travel north to the city of Saint Louis (DAK 301-201 Saint Louis & Touba) and enjoy the famous “tchay bon djenn” hosted by a local family and Senegalese wrestling. Take a trip in a Pirogue to Ngor Island where surfers and locals meet. Visit the Pink Lake to see and learn from local salt harvesters. Discover the history of the Dakar slave trade with a visit to Goree Island (DAK 101 Goree Island), one of the major slave trading posts from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s, where millions of enslaved men, women and children made their way through the “door of no return.” Touba (DAK 107-301 Holy City of Touba & Thies Market), a city just a few hours inland from Dakar, is home to Africa’s second-largest mosque. Don’t leave Senegal without exploring one of the many outdoor markets (DAK 109-202 Sandaga market) with local crafts (DAK 105-301 Dakar Art Workshop) and traditional jewelry made by the native Fulani Senegalese tribe. Check out this great video on the Documentary Photography field lab from the 2015 Voyage! Highlights: Cultural Highlights: Art and Architecture: Every day: DAK 104-101/201/301/401 Pink Lake Retba & Day 2: DAK 112-201 African Renaissance, -

China-Assisted Wrestling Arena Welcomed by Senegalese Society by Hu Zexi, Zhang Penghui, Li Zhiwei, Liu Lingling from People’S Daily

China-assisted wrestling arena welcomed by Senegalese society By Hu Zexi, Zhang Penghui, Li Zhiwei, Liu Lingling from People’s Daily A China-aided arena for traditional Senegalese wrestling, a gift presented by China to the West African country, is greeted by all locals of the sports-loving country, who believe that as an epitome of bilateral cooperation, the project not only brings tangible benefits to locals, but also adds impetus for local development. “The National Grand Theater, the Museum of Black Civilization and the National Wrestling Arena, built with Chinese assistance, stand as important venues to carry forward the culture and traditions of Senegal,” Chinese President Xi Jinping wrote in a signed article published on mainstream Senegalese newspaper ahead of his state visit to the African country. The upcoming delivery of the monumental structure designed by Chinese companies and being built by them is a big event for local residents, since wrestling is a national sport that has conquered the heart of all Senegalese. As an immensely popular sport in Senegal, wrestling also means “remain true to original aspiration, and strive for glory” in local language. The modern structure, sitting on 7 hectares of land with 18,000 square meters of floor area, is soon be delivered after two-year-long construction. Senegalese government acknowledged the construction of the project in the exchange notes it inked with Chinese government in February 2014, and then signed construction contract with Hunan Construction Engineering Group in December 2015. Comparing the structure as “a precious gemstone in Dakar, capital and largest city of Senegal”, the mainstream Senegalese newspaper Le Soleil said it will “shine on the whole West Africa”. -

Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women's Writing

Through A Female Lens: Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women's Writing Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Mutunda, Sylvester Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 13:05:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194161 THROUGH A FEMALE LENS: ASPECTS OF MASCULINITY IN FRANCOPHONE AFRICAN WOMEN’S WRITING By Sylvester N. Mutunda _____________________ Copyright © Sylvester N. Mutunda 2009 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH AND ITALIAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN FRENCH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sylvester Mutunda entitled Through A Female Lens: Aspects of Masculinity in Francophone African Women’s Writing and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Irène Assiba d’Almeida ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Jonathan Beck ___________________________________________ Date: 5/01/09 Phyllis Taoua Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Danielle Sirek, Phd Candidate [email protected] 418-5340 Supervisor: Dr

MUSICKING AND IDENTITY IN GRENADA: STORIES OF TRANSMISSION, REMEMBERING, AND LOSS DANIELLE DAWN SIREK A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by the Manchester Metropolitan University December 2013 For my family, for my colleagues, for my students: May you find stories of ‘who you are’, and feel connected to others, through your musicking ii Acknowledgements I am grateful for the unending support, academic and personal, that I have received throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Firstly I would like to thank my husband Adam Sirek, my parents Kim and Marius LaCasse, and my father- and mother-in-law Jan and Elizabeth Sirek, who have been my constant support in every possible way throughout this journey. My thankfulness to you is immeasurable. And to my baby Kathryn, whose smiles were a constant source of strength and encouragement, my thanks and love to you. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my co-supervisory team, Drs Felicity Laurence and Byron Dueck, who devoted seemingly unending hours closely analysing my thesis, discussing ideas with me, and providing me with encouragement and inspiration in many more ways than just academic. I am truly grateful for their guidance, expertise, and for being so giving of their time and of themselves. I learned so much more than research techniques and writing style from both of them. -

"All That Glitters Is Not Junkanoo": the National Junkanoo Museum And

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 "All That Glitters Is Not Junkanoo" the National Junkanoo Museum and the Politics of Tourism and Identity Ressa MacKey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE “ALL THAT GLITTERS IS NOT JUNKANOO” THE NATIONAL JUNKANOO MUSEUM AND THE POLITICS OF TOURISM AND IDENTITY By RESSA MACKEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded Fall Semester, 2009 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Ressa Mackey defended on August 18, 2009. __________________________________ Roald Nasgaard Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Karen Bearor Committee Member __________________________________ Michael Carrasco Committee Member Approved: _______________________________ Adam Jolles, Co-Chair, Department of Art History _______________________________ Sally McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii To Michael and Abigail iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank the members of my committee, Roald Nasgaard, Karen Bearor, and Michael Carrasco, whose guidance and patience tremendously benefitted my project. I am also grateful for the opportunities afforded to me by the Penelope E. Mason Grant, which enabled me to witness the Junkanoo festival and interview several of the Junkanoo artists. My understanding of the festival was truly enriched by the testimonies provided by Stan Burnside, Angelique McKay, Mornette Curtis, Jackson Burnside, and Eddy Dames.