Ru S Sia and Her Colonies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

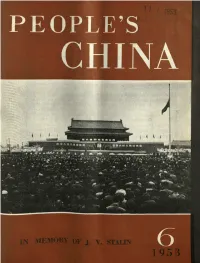

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

Body – Identy – Society

Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 61(2), 279–282 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/022.2016.61.2.1 Body – Iden ty – Society Guest Editor’s Remarks on the Thema c Block Katalin Juhász Ins tute of Ethnology, RCH, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest Recently, at the XII International Congress of Finno-Ugric Studies (Oulu, Finland, 2015), within the framework of the 17th Symposium: Body – Identity – Society: Concepts of the Socially Accepted Body, there was an interdisciplinary dialogue initiated by Hungarian scholars. The main organizer of the panel was Katalin Juhász, senior research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology in the RCH of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.1 Scholars from Finland, Hungary, Austria and Russia responded to the call for papers. Following the successful symposium, the participants wished to publish the proceedings. Katalin Juhász selected a handful of representative papers for Acta Ethnographica Hungarica . In the present 2016/2 issue of the journal, the revised papers are presented with the guest editorial work of her. The papers in this thematic block, Body – Identity – Society: Concepts of the Socially Accepted Body, introduce various aspects of the topic of cleanliness and purity from the perspectives of ethnography, anthropology, and linguistic and literary studies. The papers offer an overview of concepts, theoretical interpretations, methodological approaches, and fi eld research summaries. In anthropology, the attention paid to the issues of cleanliness and purity has increased since the theoretical trend established by the publication of Mary Douglas’ seminal book Purity and Danger on purity and pollution (D 1966). It has been a generally accepted understanding in anthropology that purity and pollution are culturally defi ned categories. -

CONTENTS 1. MODERN RESEARCH in the FIELD of ENGINEERING SCIENCES Artemenko M

CONTENTS 1. MODERN RESEARCH IN THE FIELD OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES Artemenko M. Botanical Composition and the Composition of the Ration of the European Roe Deer 11 Bovsunivska V. Methodical Aspects of Forest Management in the SE «Narodychi SF» 13 Bruzda O. Features of Eutrophicated Processes in Reservoirs for Economic and Household Use in Zhytomyr Region 16 Byrko O. The Use of Superhard Materials in Mechanical Cutting 18 Chumak A. State of the Surface Layer of Products from Non-ferrous Metals and Non-Metallic Materials Formed During Diamond Microturning and Polishing 20 Demianyk D. La Chromatographie Sur Couche Mince et Son Rôledans le Contrôle de la Qualité des Aliments 21 Dyakov S. Analysis of Methods for Processing Flat Surfaces by Widely Versatile Cutters 23 Dubchenko Ye., Chapska K. The Specification of Diamond Rope Torsional Rigidity Coeficient to Refine the Physico-Mathematical Model of Natural Stone Sawing Process 24 Goretska O. Die Analyse und ökologische Schätzung des Trinkwassers im Kommunalwerk "Zhytomyrwodokanal" 26 Hadaychuk S. Design and Technology Parameters of Non-Stationary Cutting when Processing by Single- and Multi-Blade Tool 28 Ischenko A., Kuzmin K. Determination of Keeping Storage Parts at Car Enterprise Warehouse 29 Kalinichenko O. Computer Simulation of the M1 Category Vehicle Motion 5 Using the Suspension Based on Four-Link Lever Mechanism 31 Karachun V. Improving Environmental Situation in Zhytomyr City by Organizing Rent of Electric Vehicles 34 Karimbetova N., Shapovalova O. Measurment of the Movement Parameters of Elements of Diamond Wire Saw 36 Karpova D. Cancer Morbidity Caused by the Ecological Situation in Zhytomyr Region 38 Kotkov Y. -

Investment Projects of the Republic of Dagestan Index

INVESTMENT PROJECTS OF THE REPUBLIC OF DAGESTAN INDEX INNOVATION Construction of a round and shaped steel tubes ............................. 00 producing plant Construction of the “Mountain Resources” .........................................00 Development of in-car electronics manufacturing .........................00 education and display center in Makhachkala (audio sets, starters, alternators) Construction of an IT-park of complete ............................................... 00 Construction of the “Viaduk” customs ..................................................00 “idea-series” cycle type and logistics centre Development of high-effi ciency .............................................................00 Reconstruction of the Makhachkala ..................................................... 00 solar cells and modules production commercial sea port (facilities of the second stage) Construction of the KamAZ vehicles trade ......................................... 00 INDUSTRY AND TRANSPORT and service centers in the districts of the Republic of Dagestan Development of fl oat glass production............................................... 00 Investment sites ...........................................................................................00 Development of nitric and sulfuric acid, .............................................00 and high analysis fertilizer production FUEL AND ENERGY COMPLEX onsite the “Dagfos” OJSC – II stage Construction of an intra-zone .................................................................00 -

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea Region

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication Case Chapter 2 Constructing Karelia: Myths and Symbols in the Multiethnic Reality Ilja Solomeshch 1. Power of symbols Specialists in the field of semiotics note that in times of social and political crises, at Political symbolism is known to have three the stage of ideological and moral disintegra- major functions – nominative, informative tion, some forms of the most archaic kinds of and communicative. In this sense a symbol in political symbolism reactivate in what is called political life plays one of the key roles in struc- the archaic syndrome. This notion is used, for turing society, organising interrelations within example, to evaluate the situation in pre- and the community and between people and the post-revolutionary (1917) Russia, as well as various institutions of state. Karelia Karelia is a border area between Finland and Russia. Majority of its territory belongs to Russian Republic of Karelia, with a capital in Petrozavodsk. The Sovjet Union gained the marked area from Finland as the outcome of war 1944. Karelia can be compared with similar border areas in the Baltic Region, like Schleswig-Holstein, Oppeln (Opole) Silesia in Poland, Kaliningrad region in Russia. Probably the best known case of such an area in Europe is Alsace- -Lorraine. Map 13. Karelia. Ill.: Radosław Przebitkowski The Soviet semioticity When trying to understand historical and cultural developments in the Russian/Soviet/Post-Soviet spatial area, especially in terms of Centre-Peripheries and Break-Continuity paradigms, one can easily notice the semioticity of the Soviet system, starting with its ideology. -

Eastern Finno-Ugrian Cooperation and Foreign Relations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Eastern Finno-Ugrian cooperation and foreign relations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4gc7x938 Journal Nationalities Papers, 29(1) ISSN 0090-5992 Author Taagepera, R Publication Date 2001-04-24 DOI 10.1080/00905990120036457 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nationalities Papers, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2001 EASTERN FINNO-UGRIAN COOPERATION AND FOREIGN RELATIONS Rein Taagepera Britons and Iranians do not wax poetic when they discover that “one, two, three” sound vaguely similar in English and Persian. Finns and Hungarians at times do. When I speak of “Finno-Ugrian cooperation,” I am referring to a linguistic label that joins peoples whose languages are so distantly related that in most world contexts it would evoke no feelings of kinship.1 Similarities in folk culture may largely boil down to worldwide commonalities in peasant cultures at comparable technological stages. The racial features of Estonians and Mari may be quite disparate. Limited mutual intelligibility occurs only within the Finnic group in the narrow sense (Finns, Karelians, Vepsians, Estonians), the Permic group (Udmurts and Komi), and the Mordvin group (Moksha and Erzia). Yet, despite this almost abstract foundation, the existence of a feeling of kinship is very real. Myths may have no basis in fact, but belief in myths does occur. Before denigrating the beliefs of indigenous and recently modernized peoples as nineteenth-century relics, the observer might ask whether the maintenance of these beliefs might serve some functional twenty-first-century purpose. The underlying rationale for the Finno-Ugrian kinship beliefs has been a shared feeling of isolation among Indo-European and Turkic populations. -

List of Persons and Entities Under EU Restrictive Measures Over the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine

dhdsh PRESS Council of the European Union EN List of persons and entities under EU restrictive measures over the territorial integrity of Ukraine List of Persons Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information 1. Sergey Valeryevich DOB: 26.11.1972. Aksyonov was elected 'Prime Minister of Crimea' in the Crimean 17.3.2014 AKSYONOV, Verkhovna Rada on 27 February 2014 in the presence of pro-Russian POB: Beltsy (Bălţi), gunmen. His 'election' was decreed unconstitutional by the acting Sergei Valerievich now Republic of Ukrainian President Oleksandr Turchynov on 1 March 2014. He actively AKSENOV (Сергей Moldova lobbied for the 'referendum' of 16 March 2014 and was one of the co- Валерьевич signatories of the ’treaty on Crimea´s accession to the Russian AKCëHOB), Federation’ of 18 March 2014. On 9 April 2014 he was appointed acting Serhiy Valeriyovych ‘Head’ of the so-called ‘Republic of Crimea’ by President Putin. On 9 AKSYONOV (Сергiй October 2014, he was formally ‘elected’ 'Head' of the so-called 'Republic Валерiйович Аксьонов) of Crimea'. Aksyonov subsequently decreed that the offices of ‘Head’ and ‘Prime Minister’ be combined. Member of the Russia State Council. 1/83 dhdsh PRESS Council of the European Union EN Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information 2. Rustam Ilmirovich DOB: 15.8.1976 As former Deputy Minister of Crimea, Temirgaliev played a relevant role 17.3.2014 TEMIRGALIEV in the decisions taken by the ‘Supreme Council’ concerning the POB: Ulan-Ude, ‘referendum’ of 16 March 2014 against the territorial integrity of Ukraine. (Рустам Ильмирович Buryat ASSR He lobbied actively for the integration of Crimea into the Russian Темиргалиев) (Russian SFSR) Federation. -

My Birthplace

My birthplace Ягодарова Ангелина Николаевна My birthplace My birthplace Mari El The flag • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno- Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva, Komis (Zyrians) ,Karelians ,Komi-Permians ,Maris (Cheremises), Mordvinians (Erzas and Mokshas), Udmurts (Votiaks) ,Vepsians ,Mansis (Voguls) ,Saamis (Lapps), Khanti. Mari people speak a language of the Finno-Ugric family and live mainly in Mari El, Russia, in the middle Volga River valley. • http://aboutmari.com/wiki/Этнографические_группы • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9NpQZZGuPI&feature=r elated • The rich history of Mari land has united people of different nationalities and religions. At this moment more than 50 ethnicities are represented in Mari El republic, including, except the most numerous Russians and Мari,Tatarians,Chuvashes, Udmurts, Mordva Ukranians and many others. Compare numbers • Finnish : Mari • 1-yksi ikte • 2-kaksi koktit • 3- kolme kumit • 4 -neljä nilit • 5 -viisi vizit • 6 -kuusi kudit • 7-seitsemän shimit • 8- kahdeksan kandashe • the Mari language and culture are taught. Lake Sea Eye The colour of the water is emerald due to the water plants • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno-Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva. • We have our language. We speak it, study at school, sing our tuneful songs and listen to them on the radio . Mari people are very poetic. Tourism Mari El is one of the more ecologically pure areas of the European part of Russia with numerous lakes, rivers, and forests. As a result, it is a popular destination for tourists looking to enjoy nature. -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

North Caucasus Image Inside Russia in the Context of Tourism Cluster Development

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XII, vol. 28, no. 1, 2020, p.275-288 ISSN 2065-1198, E-ISSN 2065-0817 DOI 10.30892/gtg.28122-469 NORTH CAUCASUS IMAGE INSIDE RUSSIA IN THE CONTEXT OF TOURISM CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT Tatiana LITVINOVA* Moscow State Institute of International Relations, Department of Regional Governance and National Politics, 143000, 3, Odintsovo, Novo-Sportivnaya st., Russia, Moscow region, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Litvinova T.N. (2020). NORTH CAUCASUS IMAGE INSIDE RUSSIA IN THE CONTEXT OF TOURISM CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 28(1), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.28122-469 Abstract: The article is devoted to the North Caucasus image assessment inside Russia as the important factor of tourists’ attraction to this territory. The growth of tourist cluster in the North Caucasus is one of the main tasks written in Strategy of socio-economic development of the North Caucasus Federal District untill 2025. But in the public opinion of Russians the North Caucasus was for many years perceived as a territory of socio-political instability. The research is based on the Internet survey conducted by author (n=1012). The results of survey are matched with mass media news about tourist objects development and also compared with statistic of visits of the North Caucasus by Russian and foreign citizens. The conclusion says about the growth of positive assessments of the North Caucasus image among Russians, but some stereotypes still remain. The ski resorts in Dombay and Elbrus region, which are in demand among lovers of skiing, need modernization and expansion of infrastructure. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

Supplemental Fig. 4

21 1 563 (45) R1a2b Kazakhs Kazakhs Kaz1 46 24 3 564 (146) R1a2b Iraqi-Jews Iraqi-Jews ISR40 148 22 2 569 (109) R1a2b Bengali West-Bengal Beng2 110 27 2 571 (107) R1a2b Gupta Uttar-Pradesh Gupta1 108 19 5 560 (116) R1a2b Middle-caste Orissa OrMc1 117 3 574 18 (141) R1a2b Kurmi Uttar-Pradesh Kurmi1 143 29 0 585 0 573 (82) R1a2b Ishkasim Tajiks Ishk1 83 39 (274) R1a2b Cossacks Cossacks Cosk2 284 27 0 586 (88) R1a2 Ishkasim Tajiks Ishk2 89 31 (47) R1a2 Rushan-Vanch Tajiks RVnch2 48 0 584 10 (222) R1a2c Altaians Altaians Altai5 230 24546 5 0 587 (84) R1a2c Kyrgyz Kyrgyz Kyrgz2 85 3 545 2 0 544 (22) R1a2c Kyrgyz Kyrgyz Kyrgz4 22 3 (89) R1a2c Kyrgyz Kyrgyz Kyrgz3 90 39 1 588 1 580 (15) R1a2 Assyrians Assyrians Assyr1 15 30 (93) R1a2 Ashkenazi-Jews Ashkenazi-Jews ISR10 94 115 (73) R1a2d Balkars Balkars Balkar2 74 35 1 589 (148) R1a2d Mumbai-Jews Mumbai Israel42 150 2 0 590 23 547 (23) R1a2d Shugnan Tajiks Shugn1 23 4 0 583 (245) R1a2d Circassians Circassians Cirkas3 253 0 592 24 (90) R1a2d Iraqi-Jews Iraqi-Jews ISR01 91 0 591 31 1 579 (81) R1a2d Rushan-Vanch Tajiks RVnch1 82 27 (272) R1a2d Azerbaijanis Azerbaijanis Azerb24 282 44 (120) R1a2 Iranians Iranians Iran3 121 2 0 582 23 542 (74) R1a2a Altaians Altaians Altai3 75 3 (142) R1a2a Altaians Altaians Altai4 144 5 570 3 (80) R1a2a Kyrgyz Tdj Kyrgyz KyrgzTJ2 81 18550 7 0 549 (86) R1a2a Kyrgyz Tdj Kyrgyz KyrgzTJ1 87 1 (87) R1a2a Kyrgyz Tdj Kyrgyz KyrgzTJ3 88 2 581 25 2 559 (242) R1a1c Hungarians Hungarians Hun 3 250 16 0 561 (268) R1a1c Cossacks Kuban Cossacks CoskK2 276 19 6 562 (20) R1a1c Ukrainians