Poles Apart Book Launch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historians, Tasmania

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 72 THE VON STIEGLITZ COLLECTION Historians, Tasmania INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.von Stieglitz Family Papers 2.Correspondence 3.Financial Records 4.Typescripts 5.Miscellaneous Records 6.Newspaper Cuttings 7.Historical Documents 8.Historical Files 9.Miscellaneous Items 10.Ephemera 11.Photographs OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION Karl Rawdon von Stieglitz was born on 19 August 1893 at Evandale, the son of John Charles and Lillian Brooke Vere (nee Stead) von Stieglitz. The first members of his family to come to Van Diemen’s Land were Frederick Lewis von Stieglitz and two of his brothers who arrived in 1829. Henry Lewis, another brother, and the father of John Charles and grandfather of Karl, arrived the following year. John Charles von Stieglitz, after qualifying as a surveyor in Tasmania, moved to Northern Queensland in 1868, where he worked as a surveyor with the Queensland Government, later acquiring properties near Townsville. In 1883, at Townsville he married Mary Mackenzie, who died in 1883. Later he went to England where he married Lillian Stead in London in 1886. On his return to Tasmania he purchased “Andora”, Evandale: the impressive house on the property was built for him in 1888. He was the MHA for Evandale from 1891 to 1903. Karl von Stieglitz visited England with his father during 1913-1914. After his father’s death in 1916, he took possession of “Andora”. He enlisted in the First World War in 1916, but after nearly a year in the AIF (AMC branch) was unable to proceed overseas due to rheumatic fever. -

To View All of the Historic RYCT Office Bearers

Year Commodore-in-Chief / Patron Commodore Vice Commodore Rear Commodore 1880 1881 Sir J H LeFroy Patron H J Stanley H S Barnard 1881 1882 Sir George Strahan K.C.M.G. Patron H J Stanley H S Barnard 1882 1883 H J Stanley H S Barnard 1883 1884 A G Webster H S Barnard 1884 1885 A G Webster H S Barnard 1885 1886 A G Webster H S Barnard 1886 1887 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB A G Webster H S Barnard 1887 1888 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB A G Webster H W Knight 1888 1889 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB A G Webster H W Knight 1889 1890 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB A G Webster H W Knight 1890 1891 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB A G Webster H W Knight 1891 1892 Sir Robert Hamilton KCB H W Knight W J Watchorn 1892 1893 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight W J Watchorn G.C.M.C 1893 1894 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight W J Watchorn G.C.M.C 1894 1895 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight R Sawyers G.C.M.C 1895 1896 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight R Sawyers G.C.M.C 1896 1897 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight R Sawyers G.C.M.C 1897 1898 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight R Sawyers G.C.M.C 1898 1899 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight F N Clarke G.C.M.C 1899 1900 The Rt Hon Viscount Gormanston H W Knight F N Clarke G.C.M.C 1900 1901 Capt Sir Arthur Havelock G.C.S.I. -

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Editor Dr Richard A Benton Editor: Dr Richard Benton The Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence is published annually by the University of Waikato, Te Piringa – Faculty of Law. Subscription to the Yearbook costs NZ$40 (incl gst) per year in New Zealand and US$45 (including postage) overseas. Advertising space is available at a cost of NZ$200 for a full page and NZ$100 for a half page. Communications should be addressed to: The Editor Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence School of Law The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 New Zealand North American readers should obtain subscriptions directly from the North American agents: Gaunt Inc Gaunt Building 3011 Gulf Drive Holmes Beach, Florida 34217-2199 Telephone: 941-778-5211, Fax: 941-778-5252, Email: [email protected] This issue may be cited as (2010) Vol 13 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence. All rights reserved ©. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher. ISSN No. 1174-4243 Yearbook of New ZealaNd JurisprudeNce Volume 13 2010 Contents foreword The Hon Sir Anand Satyanand i preface – of The Hon Justice Sir David Baragwanath v editor’s iNtroductioN ix Dr Alex Frame, Wayne Rumbles and Dr Richard Benton 1 Dr Alex Frame 20 Wayne Rumbles 29 Dr Richard A Benton 38 Professor John Farrar 51 Helen Aikman QC 66 certaiNtY Dr Tamasailau Suaalii-Sauni 70 Dr Claire Slatter 89 Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie 112 The Hon Justice Sir Edward Taihakurei Durie 152 Robert Joseph 160 a uNitarY state The Hon Justice Paul Heath 194 Dr Grant Young 213 The Hon Deputy Chief Judge Caren Fox 224 Dr Guy Powles 238 Notes oN coNtributors 254 foreword 1 University, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, I greet you in the Niuean, Tokelauan and Sign Language. -

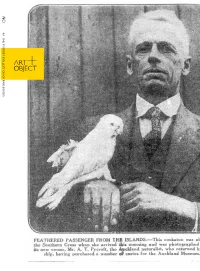

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Governor-General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy

New Zealand’s Governor General The Governor-General is a symbol of unity and leadership, with the holder of the Office fulfilling important constitutional, ceremonial, international, and community roles. Kia ora, nga mihi ki a koutou Welcome “As Governor-General, I welcome opportunities to acknowledge As New Zealand’s 21st Governor-General, I am honoured to undertake success and achievements, and to champion those who are the duties and responsibilities of the representative of the Queen of prepared to assume leadership roles – whether at school, New Zealand. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the role of the Sovereign’s representative has changed – and will continue community, local or central government, in the public or to do so as every Governor and Governor-General makes his or her own private sector. I want to encourage greater diversity within our contribution to the Office, to New Zealand and to our sense of national leadership, drawing on the experience of all those who have and cultural identity. chosen to make New Zealand their home, from tangata whenua through to our most recent arrivals from all parts of the world. This booklet offers an insight into the role the Governor-General plays We have an extraordinary opportunity to maximise that human in contemporary New Zealand. Here you will find a summary of the potential. constitutional responsibilities, and the international, ceremonial, and community leadership activities Above all, I want to fulfil New Zealanders’ expectations of this a Governor-General undertakes. unique and complex role.” It will be my privilege to build on the legacy The Rt Hon Dame Patsy Reddy of my predecessors. -

Hordern House Rare Books • Manuscripts • Paintings • Prints

HORDERN HOUSE RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS A second selection of fine books, maps & graphic material chiefly from THE COLLECTION OF ROBERT EDWARDS AO VOLUME II With a particular focus on inland and coastal exploration in the nineteenth century 77 VICTORIA STREET • POTTS POINT • SYDNEY NSW 2011 • AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE (02) 9356 4411 • FAX (02) 9357 3635 www.hordern.com • [email protected] AN AUSTRALIAN JOURNEY A second volume of Australian books from the collection of Robert Edwards AO n the first large catalogue of books from the library This second volume describes 242 books, almost all of Robert Edwards, published in 2012, we included 19th-century, with just five earlier titles and a handful of a foreword which gave some biographical details of 20th-century books. The subject of the catalogue might IRobert as a significant and influential figure in Australia’s loosely be called Australian Life: the range of subjects modern cultural history. is wide, encompassing politics and policy, exploration, the Australian Aborigines, emigration, convicts and We also tried to provide a picture of him as a collector transportation, the British Parliament and colonial policy, who over many decades assembled an exceptionally wide- with material relating to all the Australian states and ranging and beautiful library with knowledge as well as territories. A choice selection of view books adds to those instinct, and with an unerring taste for condition and which were described in the earlier catalogue with fine importance. In the early years he blazed his own trail with examples of work by Angas, Gill, Westmacott and familiar this sort of collecting, and contributed to the noticeable names such as Leichhardt and Franklin rubbing shoulders shift in biblio-connoisseurship which has marked modern with all manner of explorers, surgeons, historians and other collecting. -

Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere

TREATY RESEARCH SERIES TREATY OF WAITANGI RESEARCH UNIT ‘A Terrible and Fatal Man’: Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere Regna non merito accidunt, sed sorte variantur States do not come about by merit, but vary according to chance Cyprian of Carthage Bernard Cadogan Copyright © Bernard Cadogan This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers. 1 Introduction We are proud to present our first e-book venture in this series. Bernard Cadogan holds degrees in Education and History from the University of Otago and a D. Phil from Oxford University, where he is a member of Keble College. He is also a member of Peterhouse, Cambridge University, and held a post-doctoral fellowship at the Stout Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington in 2011. Bernard has worked as a political advisor and consultant for both government and opposition in New Zealand, and in this context his roles have included (in 2011) assisting Hon. Bill English establish New Zealand’s Constitutional Review along the lines of a Treaty of Waitangi dialogue. He worked as a consultant for the New Zealand Treasury between 2011 and 2013, producing (inter alia) a peer-reviewed published paper on welfare policy for the long range fiscal forecast. Bernard is am currently a consultant for Waikato Maori interests from his home in Oxford, UK, where he live s with his wife Jacqueline Richold Johnson and their two (soon three) children. -

New Zealand Rulers and Statesmen from 1840 To

NEWZfiALAND UUUflflUUUW w RULERS AND STATESMEN I i iiiiliiiiiiiiii 'Hi"' ! Ml! hill i! I m'/sivrr^rs''^^'^ V}7^: *'- - ^ v., '.i^i-:f /6 KDWARD CIRHON WAKEKIELI). NEW ZEALAND RULERS AND STATESMEN Fro}n 1840 to 1897 WILLIAM GISBORNE FOK.MFRLV A IMEMREK OF THE HOUSE OK KE FRESENTATIVES, AND A RESPONSIIiLE MINISTER, IN NEW ZEALAND WITH NUMEROUS PORTRAITS REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION P. C. D. LUCKIE LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY Liviitcd Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, B.C. 1897 — mi CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Introductory—Natives— First colonization—Governor Hobson Chief Justice Sir William Martin —-Attorney-General Swain- son—Bishop Selwyn—Colonel Wakefield—-New Zealand Company—Captain Wakefield — Wairau massacre— Raupa- raha—Acting-Governor Shortland—Governor Fitzroy . CHAPTER II. Governor Sir George Grey, K.C.B.—Lieutenant-Governor Eyre —New Constitution— Progress of Colonization— Recall of Governor Sir George Grey ....... 33 CHAPTER III. Representative institutions — Acting-Governor Wynyard—Mr. Edward Gibbon Wakefield—Mr. James Edward FitzGerald Dr. Featherston—Mr. Henry Sewell—Sir Frederick Whitaker —Sir Francis Bell— First Parliament—Responsible govern- ment—Native policy—Sir Edward Stafford—Mr. William Richmond—Mr. James Richmond—Sir Harry Atkinson Richmond-Atkinson family .... • • • 57 CHAPTER IV. Sir William Fox— Sir W'illiam Fitzherbert—Mr. Alfred Domett —Sir John Hall ......... 102 —— vi Contents CHAPTER V. I'AGE Session of 1856— Stafford Ministry— Provincial Question— Native Government—Land League—King Movement—Wi Tami- hana— Sir Donald McLean— Mr. F. D. Fenton —Session of 1858—Taranaki Native Question—Waitara War—Fox Ministry—Mr. Reader Wood—Mr. Walter Mantell— Respon- sible Government— Return of Sir George Grey as Governor —Domett Ministry—Whitaker-Fox Ministry . -

The First One Hundred 1890

THE GRAND LODGE OF ANTIENT, FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS 017 TASMANIA THE FIRST ONE HUNDRED YEARS 1890 - 1990 FOREWORD The initial research leading up to this publication was carried out by Wor. Bro. Hugh Middleton. We thank him for painstakingly examining the reports and minutes that reflect the activities of the Grand Lodgeof Tasmania over the last 100 years. This volume does not purport to be a historyof freemasonry in Tasmania, This would entail a close look at the records of individual lodges. But we have here a historical record of freemasonry in Tasmania as seen by the Grarid Masters and the Boards of General Purposes. You will find excerpts from what must have been stirring speeches at the time of their delivery. They still make good reading. You will wonder at the fortitude of our brethren who travelled the length and breadth of Tasmania in the early days. Indeed they travelled by sea to get to the West Coast. If this book is nothing more it is an acknowledgement that the freemasons of 1990 give thanks to their predecessorswho worked so hard to establish the craft in Tasmania. M.L. YAXLEY Chairman, Editorial Committee EDITORIALCOMMITTEE The original research for this volume was conducted by Wor. Bro. Hugh Middleton'.Upon his resignation in 1983 an editori�I committee was formedand the work was continued by. V. Wor. Bro. M. Davis Wor. Bro. N. Dunbar V. Wor. Bro. M.L. Yaxley (Chairman) INDEX Page No. Foreword Index of Grand Masters 1. The Beginningsof Freemasonryin Van Diernen'sLand 1 2. Formation of the Grand Lodge of Tasmania 10 3. -

Equal Subjects, Unequal Rights

CHAPTER THREE Australasia: one or two ‘honorable cannibals’ in the House? The first colonies on the Australian continent and the islands of New Zealand in the decades from the late 1830s to 1870 were notable for their swift movement politically from initial Crown colonies to virtual local self-government. As in Canada, the British Government first made arrangements for representative government based on a property franchise for all of these colonies, the already existing and the new, and then conceded responsible government to the colonists. Further, by 1860 the legislatures of the eastern and south-eastern Australian colo- nies had instituted full manhood suffrage. Formally, the Indigenous peoples of the Australasian colonies, Aborigines and Maori, were included in this rush along the path to self-government and democracy. Closer examination reveals that colonists on the Australian continent could afford to show contemptuous disregard of Aborigines’ involve- ment in political processes. New Zealand settlers, by contrast, would need to surround their initially fragile dominance of the colony with safeguards against Maori potential to influence their political agendas. White Canadians explicitly and consciously enshrined in law that Indigenous political rights were dependent on ‘progress’ in ‘civilisa- tion’. In the Australasian colonies, that agenda also would never be far from the surface, interwoven with urgent settler imperatives grounded in their intensive pursuit of their own economic interests. The means by which colonists could acquire -

Waitara Endowments Interim Report (Draft)

Waitara Endowments Interim Report (Draft) Waitara late 1960s (Taranaki Museum Negative LN1210) 1.1..1 November 2002 Rachael Willan 1 INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 THE LAND 6 1.2 SUMMARY 7 REPORT BRIEF 7 MAIN ISSUES 8 PEKAPEKA & THE HARBOUR TRUST – POINTS OF CLARIFICATION 11 SOURCES 11 2 SEEDS OF CONFLICT - LAND HISTORY 1840 - 1860 12 INTRODUCTION 12 2.1 THE PEKAPEKA BLOCK 12 HAPU & HISTORY 12 PEKAPEKA ‘PURCHASE’ 13 THE 1840S – EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT AND EARLY LAND PURCHASE 14 THE CROWN INVESTIGATES THE NGA MOTU PURCHASE 14 WIREMU KINGI TE RANGITAKE - EARLY OPPOSITION TO LAND SALE AT WAITARA 15 THE 1850S - CONTINUED RESISTANCE TO LAND SALE 17 2.2 1860 – 1863 - WAR IN TARANAKI 17 GORE BROWNE PROMISES NOT TO BUY DISPUTED LAND 17 PURCHASE NEGOTIATIONS 18 SOVEREIGNTY 23 OTHER OPPOSITION 25 FAILURE TO INVESTIGATE OWNERSHIP 26 CONFLICT 27 ISSUES 29 3 CONFISCATION & COMPENSATION 33 INTRODUCTION 33 Interim Waitara Endowments Report 1 1861- AN UNEASY TRUCE 33 THE PEKAPEKA PURCHASE IS ABANDONED 34 RESERVES 36 FINDING ON KINGI’S RIGHTS 37 OMATA AND TATARAIMAKA 39 CONFISCATION 42 NEW ZEALAND SETTLEMENTS ACT 1863 43 THE CONFISCATION IN PRACTICE 45 COMPENSATION 46 RESERVES IN WAITARA TOWN 49 ISSUES 50 4 TOWN DEVELOPMENT & GROWTH 52 INTRODUCTION 52 4.1 SETTLEMENT AND SALES 54 4.2 RESERVES AND ENDOWMENTS 55 HARBOUR ENDOWMENTS 56 1876 - LAND VESTED IN THE HARBOUR BOARD FOR A SIGNAL STATION 57 1876 - THE FIRST ENDOWMENTS 57 1879 – RIVER FRONT LAND ACQUIRED 58 1904 – SEAFRONT LAND ACQUIRED 58 1910 – WAITARA HARBOUR BOARD AND BOROUGH EMPOWERING ACT 59 1940 - WAITARA HARBOUR -

Clark Bequest Rs.7

CLARK BEQUEST RS.7 SIR ERNEST CLARK (1864-1951) British civil servant and Governor, Sir Ernest Clark was during his career, Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, Northern Ireland, 1921-25; Director Underground Railway System of London; Member of the Economic Mission to Australia, 1928-29; Governor of Tasmania, 1933-1945. CLARK PAPERS PERSONAL PAPERS Appointments Warrant of appointment as additional member of the first class of the Order of St.Michael and St.George. 4 Aug. 1943; (0..) ((2: li~~IP'I':") , . With warrant dispensing with investiture of above Order. L') (~~$.l 'I \e,II)) 4 Aug. 1943. And "London Gazette" recording above promotion, 6 Aug. 1943". \ (~). \' \ \: \ i .(7 RS. 7/1 (a ,b ,c) v' Certificate of appointment as J.P. for Tasmania in United Kingdom. 28 Sept. 1945 Notes for Speeches Notes for and drafts of speeches under headings: Addresses at opening of Parliament; Patriotic; Economic; Humourous; Masonic; Miscellaneous.1933-45. ( (". ') (R OJ .,' i '~, i l \ .- ,\ '~r \) (3 folders) RS.7/3 (a,b,c)v \; ) R.:: ': ' ! t! .', \. " " I /.1\ ' " Letters \..(... \ ( R.~j -1 .,:" ! t, ~. f,> Farewell letters received on expiration of office as Governor and copies of replies. 1945. RS.7/4 v (r:,;::, ,:'P/,.-.(fI li') CLARK BEQUEST ctd. - 2 - RS.7 OFFICIAL PAPERS 1I0 pen ing of the Parliament of Northern Ireland by His Most Gracious Majesty King George V. June 22nd 1921" Printed. 31p. IIVisit of their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of York to Northern Ireland, 19th-26th July, 1924". Printed. 30p. Pencil annotations Correspondence relating to exchange of English and Victorian ra 11 way employees.