Equal Subjects, Unequal Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to the 1925-1927 Legislative Assembly of the Province

GENERAL INDEX TO THE Journals and Sessional Papers OF THE Legislative Assembly, Ontario 1925-1926-1927 15 GEORGE V to 17 GEORGE V. Together with an Index to Debates and Speeches and List of Appendixes to the Journals for the same period. COMPILED AND EDITED BY ALEX. C. LEWIS, Clerk of the House ONTARIO TORONTO Printed and Published by the Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty 1927 NOTE. This index is prepared for the purpose of facilitating reference to the record, in the journals of the Legislative Assembly, of any proceedings of the House at any one or more of the sessions from 1925 to 1927, inclusive. Similar indexes have been published from time to time dealing with the sessions from 1867 to 1888, from 1889 to 1900, from 1901 to 1912, from 1913 to 1920, and from 1921 to 1924, so that the publication of the present volume completes a set of indexes of the journals of the Legislature from Confederation to date. The page numbers given refer to the pages in the volume of the journals for the year indicated in the preceding bracket. An index to sessional papers, and an index to the debates and speeches for the sessions 1925 to 1927 are also in- cluded. ALEX. C. LEWIS, INDEX PAGE Index to Journals 5 Index to Sessional Papers 141 Index to Debates and Speeches 151 [4] GENERAL INDEX TO THE Journals and Sessional Papers OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE Province of Ontario FOR THE SESSIONS OF 1925, 1926 AND 1927. 15 GEORGE V TO 17 GEORGE V. -

Final Repport

Final Reportp Project code: B.PAS.0297 Prepared by: Graham Donald Date published: March 2012 PUBLISHED BY Meat & Livestock Australia Limited Locked Bag 991 NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2059 Analysis of Feed-base Audit Meat & Livestock Australia acknowledges the matching funds provided by the Australian Government to support the research and development detailed in this publication. This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA). Care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. However MLA cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in the publication. You should make your own enquiries before making decisions concerning your interests. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without prior written consent of MLA. Analysis of Feed-base Audit Contents 1 Abstract............................................................................ 8 2 Executive Summary ........................................................ 9 3 Project Objectives ......................................................... 10 4 Method ........................................................................... 11 5 Results ........................................................................... 16 6 Discussion ..................................................................... 17 7 Further Investigations .................................................. 18 8 Acknowledgements ..................................................... -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

The Coastal Talitridae (Amphipoda: Talitroidea) of Southern and Western Australia, with Comments on Platorchestia Platensis (Krøyer, 1845)

© The Authors, 2008. Journal compilation © Australian Museum, Sydney, 2008 Records of the Australian Museum (2008) Vol. 60: 161–206. ISSN 0067-1975 doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.60.2008.1491 The Coastal Talitridae (Amphipoda: Talitroidea) of Southern and Western Australia, with Comments on Platorchestia platensis (Krøyer, 1845) C.S. SEREJO 1 AND J.K. LOWRY *2 1 Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista s/n, Rio de Janeiro, RJ 20940–040, Brazil [email protected] 2 Crustacea Section, Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] AB S TRA C T . A total of eight coastal talitrid amphipods from Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia are documented. Three new genera (Australorchestia n.gen.; Bellorchestia n.gen. and Notorchestia n.gen.) and seven new species (Australorchestia occidentalis n.sp.; Bellorchestia richardsoni n.sp.; Notorchestia lobata n.sp.; N. naturaliste n.sp.; Platorchestia paraplatensis n.sp. Protorchestia ceduna n.sp. and Transorchestia marlo n.sp.) are described. Notorchestia australis (Fearn-Wannan, 1968) is reported from Twofold Bay, New South Wales, to the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. Seven Australian and New Zealand “Talorchestia” species are transferred to Bellorchestia: B. chathamensis (Hurley, 1956); B. kirki (Hurley, 1956); B. marmorata (Haswell, 1880); B. pravidactyla (Haswell, 1880); B. quoyana (Milne Edwards, 1840); B. spadix (Hurley, 1956) and B. tumida (Thomson, 1885). Two Australian “Talorchestia” species are transferred to Notorchestia: N. australis (Fearn-Wannan, 1968) and N. novaehollandiae (Stebbing, 1899). Type material of Platorchestia platensis and Protorchestia lakei were re-examined for comparison with Australian species herein described. -

ION Construction Notice

Construction Notice D St u D k L u e St St e m a n S el is g Construction Ahead: Charles, from Victoria lh u e F h t i o L r L i a W l W o b m St C c e A h u r e t v t St s e p s t S N au t t y St t ith St n S le S re lla u t n n B e t South to Borden South ha o l Lu t S S g P lin e t el i m W r e Pe H ne t N q La S El u ki ia l e s r en g ow to n W z ic St G G V W St a St o t a ki n r A E Construction of Stage 1 ION, the Region of Waterloo’s light s M o d v t w e W zo ar i o e a G e g s n s r v ar n l e A e A t o rd t A a v b na v M e A o ay e e M M M v El i e rail transit (LRT) service, is underway in select areas across S r N l e e St h e r t S n m t e t St Pl t n g St S e W e E S L r l g t l n n k S y A e c d n o u e i n v a r a i e t L C o e e em a Kitchener and Waterloo. -

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Editor Dr Richard A Benton Editor: Dr Richard Benton The Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence is published annually by the University of Waikato, Te Piringa – Faculty of Law. Subscription to the Yearbook costs NZ$40 (incl gst) per year in New Zealand and US$45 (including postage) overseas. Advertising space is available at a cost of NZ$200 for a full page and NZ$100 for a half page. Communications should be addressed to: The Editor Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence School of Law The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 New Zealand North American readers should obtain subscriptions directly from the North American agents: Gaunt Inc Gaunt Building 3011 Gulf Drive Holmes Beach, Florida 34217-2199 Telephone: 941-778-5211, Fax: 941-778-5252, Email: [email protected] This issue may be cited as (2010) Vol 13 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence. All rights reserved ©. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher. ISSN No. 1174-4243 Yearbook of New ZealaNd JurisprudeNce Volume 13 2010 Contents foreword The Hon Sir Anand Satyanand i preface – of The Hon Justice Sir David Baragwanath v editor’s iNtroductioN ix Dr Alex Frame, Wayne Rumbles and Dr Richard Benton 1 Dr Alex Frame 20 Wayne Rumbles 29 Dr Richard A Benton 38 Professor John Farrar 51 Helen Aikman QC 66 certaiNtY Dr Tamasailau Suaalii-Sauni 70 Dr Claire Slatter 89 Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie 112 The Hon Justice Sir Edward Taihakurei Durie 152 Robert Joseph 160 a uNitarY state The Hon Justice Paul Heath 194 Dr Grant Young 213 The Hon Deputy Chief Judge Caren Fox 224 Dr Guy Powles 238 Notes oN coNtributors 254 foreword 1 University, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, I greet you in the Niuean, Tokelauan and Sign Language. -

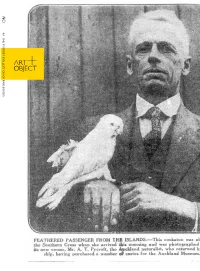

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J. -

The Governor-General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy

New Zealand’s Governor General The Governor-General is a symbol of unity and leadership, with the holder of the Office fulfilling important constitutional, ceremonial, international, and community roles. Kia ora, nga mihi ki a koutou Welcome “As Governor-General, I welcome opportunities to acknowledge As New Zealand’s 21st Governor-General, I am honoured to undertake success and achievements, and to champion those who are the duties and responsibilities of the representative of the Queen of prepared to assume leadership roles – whether at school, New Zealand. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the role of the Sovereign’s representative has changed – and will continue community, local or central government, in the public or to do so as every Governor and Governor-General makes his or her own private sector. I want to encourage greater diversity within our contribution to the Office, to New Zealand and to our sense of national leadership, drawing on the experience of all those who have and cultural identity. chosen to make New Zealand their home, from tangata whenua through to our most recent arrivals from all parts of the world. This booklet offers an insight into the role the Governor-General plays We have an extraordinary opportunity to maximise that human in contemporary New Zealand. Here you will find a summary of the potential. constitutional responsibilities, and the international, ceremonial, and community leadership activities Above all, I want to fulfil New Zealanders’ expectations of this a Governor-General undertakes. unique and complex role.” It will be my privilege to build on the legacy The Rt Hon Dame Patsy Reddy of my predecessors. -

Hordern House Rare Books • Manuscripts • Paintings • Prints

HORDERN HOUSE RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS A second selection of fine books, maps & graphic material chiefly from THE COLLECTION OF ROBERT EDWARDS AO VOLUME II With a particular focus on inland and coastal exploration in the nineteenth century 77 VICTORIA STREET • POTTS POINT • SYDNEY NSW 2011 • AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE (02) 9356 4411 • FAX (02) 9357 3635 www.hordern.com • [email protected] AN AUSTRALIAN JOURNEY A second volume of Australian books from the collection of Robert Edwards AO n the first large catalogue of books from the library This second volume describes 242 books, almost all of Robert Edwards, published in 2012, we included 19th-century, with just five earlier titles and a handful of a foreword which gave some biographical details of 20th-century books. The subject of the catalogue might IRobert as a significant and influential figure in Australia’s loosely be called Australian Life: the range of subjects modern cultural history. is wide, encompassing politics and policy, exploration, the Australian Aborigines, emigration, convicts and We also tried to provide a picture of him as a collector transportation, the British Parliament and colonial policy, who over many decades assembled an exceptionally wide- with material relating to all the Australian states and ranging and beautiful library with knowledge as well as territories. A choice selection of view books adds to those instinct, and with an unerring taste for condition and which were described in the earlier catalogue with fine importance. In the early years he blazed his own trail with examples of work by Angas, Gill, Westmacott and familiar this sort of collecting, and contributed to the noticeable names such as Leichhardt and Franklin rubbing shoulders shift in biblio-connoisseurship which has marked modern with all manner of explorers, surgeons, historians and other collecting. -

Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere

TREATY RESEARCH SERIES TREATY OF WAITANGI RESEARCH UNIT ‘A Terrible and Fatal Man’: Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere Regna non merito accidunt, sed sorte variantur States do not come about by merit, but vary according to chance Cyprian of Carthage Bernard Cadogan Copyright © Bernard Cadogan This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers. 1 Introduction We are proud to present our first e-book venture in this series. Bernard Cadogan holds degrees in Education and History from the University of Otago and a D. Phil from Oxford University, where he is a member of Keble College. He is also a member of Peterhouse, Cambridge University, and held a post-doctoral fellowship at the Stout Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington in 2011. Bernard has worked as a political advisor and consultant for both government and opposition in New Zealand, and in this context his roles have included (in 2011) assisting Hon. Bill English establish New Zealand’s Constitutional Review along the lines of a Treaty of Waitangi dialogue. He worked as a consultant for the New Zealand Treasury between 2011 and 2013, producing (inter alia) a peer-reviewed published paper on welfare policy for the long range fiscal forecast. Bernard is am currently a consultant for Waikato Maori interests from his home in Oxford, UK, where he live s with his wife Jacqueline Richold Johnson and their two (soon three) children. -

Thetimesnewtecumseth

Alliston Tel: 705 481 1584 27 Victoria St W NOW OPEN CELLPHONE, COMPUTER & Telecom Tel: 1 877 891 7851 SECURITY CAMERA Email: [email protected] Buy, Sell, Install & REPAIR Alliston • Beeton • Tottenham Friday: Saturday: Sunday: Monday: Mix of Sun A Few Chance of A Few NewTecumseth and Clouds Showers Shower Showers Visit us online at: www.newtectimes.com Local 5-day Forecast LocalBuying 5-day Forecast Local 5-day Forecast Simcoe-York Printing Local 5-day Forecast Fax: 905-729-2541 or Proofed and Weekly Circulation: 2,000 l 905-857-6626 l 1-888-557-6626 l www.newtectimes.com today Thursdaytoday Friday Thursdaytoday Saturday Friday Thursday Sunday Saturday Friday Sunday Saturday Sunday approved by . Selling $1.50 per copy ($1.43TheTimes + 7¢ G.S.T.) Thursday, September 26, 2019 today Volume Thursday 45, Issue Friday 39 Saturday Sunday Date: December 12/13 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO.0040036642 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO 30 MARTHA ST., #205, BOLTON ON L7E 5V1 2019 We acknowledge the fi nancial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Periodical Fund of the Department of Canadian Heritage. in 2014 Date of insertion: December 12/13 CALL TT q KTS q IS q • locally MARC RONAN TODAY! ORDER YOUR sourced Sales Representative/Owner CC q OC q SFP q GVS q • air chilled www.marcronan.com FRESH THANKSGIVING • grain fed Sales Rep.: AD TURKEY www.vincesmarket.ca/reserve-your-turkey 905-936-4216 Set by: JS Ronan Realty, Brokerage Each Office Is Independently Owned And Operated Not intended to solicit clients under contract or contravene the privacy act.