Vignettes, Spots & Short Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St M Newsletter No 3 Final

the church on Parliament Square by kind permission of Clare Weatherill NEWS No 3 Winter 2017 news and features from St Margaret’s LENT 2017 PRE-LENTEN ART EXHIBITION AT ST MARGARET’S Lent may originally have followed Sacred Space: drawings and paintings by Lottie Stoddart Epiphany, just as Jesus’ sojourn in the wilderness followed Over the course of 2016 I was given the immediately on his baptism, but it wonderful opportunity to spend an intensive soon became firmly attached to period drawing inside Westminster Abbey. My Easter, as the principal occasion first visit, following in the footsteps of William for baptism and for the Blake, was with the Royal Drawing School, and reconciliation of those who had formed the idea of returning and engaging with been excluded from the Church’s the Abbey's interior for a longer period. My work investigates spaces that evoke the fellowship. sacred. My previous works on this theme have This history explains the included London graveyards, ancient characteristic notes of Lent – self- woodlands and most recently tree veneration examination, penitence, self-denial, in India. Many evocations of Westminster study, and preparation for Easter. Abbey concentrate on the monumental, but I Ashes are an ancient sign of penitence; have sought out the personal and intimate from the middle ages it became the where visual juxtapositions have occurred custom to begin Lent by being marked through time, architectural style and changing in ash with the sign of the Cross. use. The Abbey's central shrine and surrounding chapels have made me consider The calculation of the forty how sacred spaces are glimpsed, hidden and days of Lent has varied considerably in revealed. -

UWGC-Chief-Executive-And-Clerk-Candidate-Brief

A Message from the Chairman Thank you very much for your interest in the role of Chief Executive and Clerk of the United Westminster and Grey Coat Foundation (UWGCF) in succession to the current Clerk who will retire at the end of this year. Until very recently the United Westminster Schools Foundation (UWS) and the Grey Coat Hospital Foundation (GCHF) were separate charities, with separate boards of trustees, which were administered by the same Foundation Office. On 31 March 2019 UWS and GCHF formally merged to become UWGCF with a single board of trustees. This creates an education charity of significant size and presents an extremely exciting opportunity for the Foundation in the years to come. We are looking for someone who is not only able to put forward strategies for Trustees to consider, but also to ensure that the current five schools are supported to help them continue to achieve excellence. These changes do not presage a change in the relationship with the Foundation’s schools; each school will retain its existing autonomy under the leadership of its respective Governing Body. The merger does, however, present opportunities to manage its endowments more effectively and to consider ways in which it can promote public benefit in a more focused and co-ordinated way than was possible before. The responsibilities of the Chief Executive and Clerk and the ideal candidate are described in this pack. You will note that the title of the post has been changed to reflect not only the traditional understanding of the term ‘Clerk’ in the field of education and other charitable organisations, but also to encompass the wide responsibility for all the executive functions of the office. -

September 2016

City of Westminster SEN Key Worker, Case Worker and Educational Psychologist List for Schools and Colleges September 2016 Please use this list to identify the name of the SEN Key worker, case worker and Educational Psychologist that is attached to your child’s school, nursery or college If you would like to contact the SEN Service, you can do so by calling 020 7361 3311 or emailing [email protected] The manager in the SEN Service who has responsibility for Westminster is Randika Doling Educational School Setting Key Worker Case Worker Psychologist All Souls’ CE Primary School Alicia Wright Shirlie Graham Alex Haswell Ark Atwood Academy Susan Blake Zaynab Alfadhl Alison Russell Barrow Hill Junior School To be allocated Shirlie Graham Monique Davis Burdett-Coutts & Townshend Foundation CE Primary School To be allocated Shirlie Graham Alex Haswell Christ Church Bentinck CE Primary School Alicia Wright Shirlie Graham Alex Haswell Churchill Gardens Primary Academy (and resource base for SLCN) Paula Ingram Zaynab Alfadhl Monique Davis College Park School (Special) Jean Clarke Ranjna Hirani Sara Darchicourt Dorothy Gardner Centre (Nursery) Chelsea Hayward Zaynab Alfadhl Loraine Hancock Edward Wilson Primary School (and resource base for VI) Michelle Phillips Shirlie Graham Heloise Morgan Essendine Primary School Michelle Phillips Shirlie Graham Loraine Hancock Gateway Academy Michelle Ellis Ranjna Hirani Sara Roberts George Eliot Primary School Angela Enaohwo** Shirlie Graham Jessica Wren Hallfield Primary School Susan Blake Zaynab Alfadhl Sara -

Report and Financial Statements

Report and Financial Statements 2019-20 2 The United Westminster & Grey Coat Foundation, Report & Financial Statements 2019-20 The United Westminster & Grey Coat Foundation, Report & Financial Statements 2019-20 3 Charity registration number Contents 1181012 Company registration number 11464504 Reference and administrative details of the Foundation, its Trustees and advisers 2 Chief Executive Officer & Clerk R W Blackwell MA Trustees’ Report 3 - 32 (resigned 31 December 2019) Independent auditor’s report 33 - 35 Dr G A Carver MA MFA DFA FRSA (appointed 1 January 2020) Financial Statements 36 - 70 Finance Director M J Bithell MA Consolidated statement of financial activities 37 Consolidated balance sheet 38 Principal office 57 Palace Street Main Charity balance sheet 39 Westminster Consolidated statement of cash flows 40 - 41 London, SW1E 5HJ Notes to the financial statements 42 - 70 Telephone 020 7828 3055 Investment managers Sarasin and Partners LLP 100 St Paul’s Churchyard London, EC4M 8BU Bankers The United Westminster & Grey Coat National Westminster Bank plc Foundation (the ‘Foundation’) presents Victoria Branch its report for the year ended 31 August 169 Victoria Street 2020 under the Charities Act 2011 and London, SW1E 5BT the Companies Act 2006, including the Solicitors Directors’ Report and Strategic Report Browne Jacobson LLP under the Companies Act 2006, the 15th Floor Memorandum and Articles of Association 6 Bevis Marks and Accounting and Reporting by London, EC3A 7BA Charities, Statement of Recommended Trustees Cater Leydon -

ANNUAL REVIEW by April 2010, More Than 1,000,000 Had Attended Performances at the Roundhouse Since It Reopened in June 2006

ANNUAL REVIEW By April 2010, more thAn 1,000,000 hAd Attended performAnces At the roundhouse since it reopened in June 2006. ‘A sonic shrine for a whole new PsuP orters of TheSantander heAdliner President TimHailstone(Chairman) DrakeMusic TorianoJuniorSchool EmilyMomoh ProjeCts And Foundation DarrenAger Sir TorquilNormanCBE SamKatz Fairbridge Camden JudyNadel generation of music lovers’ Core Costs TheSarahD’Avigdor StephenBarry MichaelKent FamiliesinFocus TheWallaceCollection BarbaraO’Brien Time Out ArtsCouncilEngland GoldsmidCharitable RichardBerry Bo Ard of trustees AnthonyLandes FosteringNetwork WalworthAcademy ScottParker TheAtkinFoundation Fund JamesBryan NicholasAllott JuliaLandes GameRunner School,Southwark KiaPrempeh Avid SingUp DamonBuffini SarahAsiedu EricNicoli GlobeAcademy WhittingtonPark ConorRoche TheRoundhousewasvotedTime Out’s BBH MichaelSpencer JoelBygraves AnthonyBlackstock RichardReed GreyCoatHospital Community AngusScott-Miller ‘BestMusicVenue’,andnominatedforthe BDOLLP TonyTabaznik NickCandler KentakeChinyelu-Hope EllieSleeman School,Cityof Association BethThompson musicindustry’s‘FavouriteVenue’atthe BigLotteryFund BarryTownsley KentakeChinyelu-Hope MarcusDavey SanjayWadhwani Westminster WilliamEllisSecondary JessTierney Bloomberg Ultraspeed MattClack LloydDorfmanCBE Haberdashers’Aske’s SchoolCamden Development & TotalProductionInternationalAwards. TheBRITTrust v,theyouthvolunteering MarcusDavey (Chairman) AmAssBA dors HatchamCollege, Communications TheCloreDuffield charity PatricedeVilliers TonyElliott -

The Grey Coat Hospital Church of England

The Grey Coat Hospital Church of England Comprehensive School for Girls Schools must set admission arrangements annually, and where changes are proposed to admission arrangements, the school must first publicly consult on those arrangements. We are consulting on our arrangements for admissions in the 2019/20 academic year and would like to hear your comments. The proposed changes are (1) the removal of Category E, occasional church attendance for at least two years for Church of England and Other Church places and (2) to modify the existing definition of siblings so that it reads “After this, priority will be given to sisters of current Grey Coat pupils who will be on roll in years 7 to 13 at the school at the time of the admission of the younger sister” This consultation is for the attention of: a) parents of children between the ages of two and eighteen b) other persons in the area who have an interest in the proposed arrangements c) all other admission authorities within the local area d) the local authority (Westminster Council) e) any adjoining neighbouring local authorities The consultation period is between 21/11/2017 and 26/01/2018 and comments should be submitted in writing to: Roy Blackwell Clerk to the governing body The Grey Coat Hospital St Andrew's Building Greycoat Place, London SW1P 2DY If you prefer you can email your comments to : Roy.Blackwell@uws‐gch.co.uk Following the consultation period all submitted comments will be considered at a governors meeting and the final arrangements will be published on the school and Westminster Council website on 1March 2018 THE GREY COAT HOSPITAL WESTMINSTER Head Teacher Siân Maddrell Supplementary Information Form 2019-2020 Please print clearly. -

$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $$ $ $ $ $ ±Projected Change In

Projected change in population aged 11 to 15 Change in population aged 11 to 15 2013 to 2023 ± 2013 to 2023* $19 -4I4s ltoin 2g1ton Abbey Road $20 21 to 47 Brent $21 47 to 84 Regent's Park Queen's Park Maida Vale Camden 84 to 130 Harrow 130 to 300 17 Road $ Little Church Golborne Venice $ Secondary Schools Street Bryanston $23 St. Charles Westbourne $16 and College Park and Old Oak $24 $14 Dorset Marylebone 1 Square High Street $ Bayswater Notting Colville Hyde Park Barns City Lancaster Gate West End 7 Ealing $ Pembridge Wormholt and White City Norland Westminster Shepherd's Bush Green Campden St. James' 12 Knightsbridge and Belgravia 15 $ Askew $ Holland $4 Addison Queen's Gate $25 Southwark Ravenscourt H&F RBK&C Brompton Ward $22 Park Abingdon Hans Town 10 $ Avonmore and 13 Vincent $8 Brook Green $ Warwick Earl's Courtfield Square Hammersmith Court * © GLA 2012 Round Broadway Tachbrook Hounslow $18 Demographic Projections, 2013 North End Royal Hospital Churchill Redcliffe Stanley Fulham Reach $9 Hammersmith and Fulham 13, Saint Thomas More Fulham Cremorne 1, Burlington Danes Academy 14, Sion-Manning RC Girls' School Broadway 2, Fulham College Boys' School 15, The Cardinal Vaughan School $3 3, Fulham Cross Girls' School Munster $11 4, Hammersmith Academy Westminster $2 Parsons 5, Hurlingham and Chelsea 16, King Solomon Academy Richmond Town Green 6, Lady Margaret School 17,L Paadmdinbgetotnh Academy $6 and 7, Phoenix High School 18, Pimlico Academy upon Thames Palace Walham Riverside 8, Sacred Heart High School 19, Quintin Kynaston School 9, The London Oratory School 20, St Augustine's CofE High School Sands End 10, West London Free School 21, St George's Catholic School 0 0.5 1 2 Kilometers $5 22, The Grey Coat Hospital WandswKeonrstinhgton and Chelsea settings 23, The St Marylebone CofE School 11, Chelsea Academy 24, Westminster Academy Prepared by Education Data Team 03/04/2013 12, Holland Park School 25, Westminster City School. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

Impact on BSF Schools by Local Authority

Impact on BSF schools by local authority Barking and Dagenham All Saints Stopped Barking Abbey Stopped Barking Riverside Community Stopped PFI Barking Riverside Special Stopped PFI Eastbrook Stopped PFI Eastbury Stopped Jo Richardson Stopped Robert Clack Stopped Trinity Special Stopped Warren Stopped Dagenham Park Sample – for discussion PFI Sydney Russell Sample – for discussion Barnet East Barnet School Open (06/2010) Bishop Douglas RC Stopped Copthall Stopped Oak Lodge Stopped PFI St Mary's CE High Stopped The Pavillion Stopped The Ravenscroft Stopped PFI Barnsley Darton High Unaffected PFI Greenacre Unaffected Kirk Balk Unaffected PFI New School (Kingstone/Holgate) Unaffected PFI New School (Foulstone/Wombell) Unaffected PFI New School (Priory/Willowgarth) Unaffected PFI New School (Royston/Edward Sheerien) Unaffected Penistone Grammar Unaffected PFI Springwell Unaffected PFI St Michaels RC and CE Unaffected PFI The Dearne High Unaffected Bath and North East Somerset Writhlington School Open (04/2010) Bedford The Bedford Academy Academy - for discussion Biddenham Stopped Greys Centre PRU Stopped Hastingsbury Stopped Mark Rutherford Stopped Mark Rutherford - Central Campus Stopped Ridgeway Special Stopped Sharnbrook Stopped Sharnbrook Oakley Campus Stopped St John's Special Stopped St Thomas More RC Stopped Wixams Stopped Wootton Stopped Bexley Haberdashers Aske Crayford Academy Unaffected Harris Falconwood Academy Unaffected Birmingham Aston Engineering Academy UT Academy - for discussion Birmingham Ormiston Academy Unaffected College -

Private Schools Dominate the Rankings Again Parents

TOP 1,000 SCHOOLS FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday March 8 2008 www.ft.com/top1000schools2008 Winners on a learning curve ● Private schools dominate the rankings again ● Parents' guide to the best choice ● Where learning can be a lesson for life 2 FINANCIAL TIMES SATURDAY MARCH 8 2008 Top 1,000 Schools In This Issue Location, location, education... COSTLY DILEMMA Many families are torn between spending a small fortune to live near the best state schools or paying private school fees, writes Liz Lightfoot Pages 4-5 Diploma fans say breadth is best INTERNATIONAL BACCALAUREATE Supporters of the IB believe it is better than A-levels at dividing the very brainy from the amazingly brainy, writes Francis Beckett Page 6 Hit rate is no flash in the pan GETTING IN Just 30 schools supply a quarter of successful Oxbridge applicants. Lisa Freedman looks at the variety of factors that help them achieve this Pages 8-9 Testing times: pupils at Colyton Grammar School in Devon, up from 92nd in 2006 to 85th last year, sitting exams Alamy It's not all about learning CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS In the pursuit of better academic performance, have schools lost sight of the need to produce happy pupils, asks Miranda Green Page 9 Class action The FT Top 1,000 MAIN LISTING Arranged by county, with a guide by Simon Briscoe Pages 10-15 that gets results ON THE WEB An interactive version of the top notably of all Westminster, and then regarded as highly them shows the pressure 100 schools in the ranking, and more tables, The rankings are which takes bright girls in academic said the school heads feel under. -

Secondary Transfer Process 2021 Topics

Westminster City Council Secondary Transfer Process 2021 Topics • Introduction • Common myths • Overview of the process • Key dates • Advantages of the online application process • Local school options and offer details • Post-offer process and Appeals Introduction Choosing a secondary school is a big decision for you and your child. This presentation highlights the main points and key dates that you need to be aware of. Last year, over 9% of Westminster applicants were not offered one of their preferred schools, so it is extremely important to research your school options before submitting an application. Information about how places will be allocated can be found in the Secondary School brochure, available from your child’s primary school, or through the local Admissions Team. We also recommend visiting the schools on the open days/evenings that they have arranged to find out how likely it is for your child to be offered a place. At any point in the process you can contact the Admissions Team for advice; Tel: 020 7745 6433 Email: [email protected] Common Myths I will receive an I will get a place at offer at my one of the schools I nearest school. name on the form. I have a better chance of an offer at the schools I place highest on the common application form. My child has special needs and will get a place. I have overwhelming medical or social reasons for my choice of school and will I am entitled to a therefore get a place. place at a single sex school or a faith based school. -

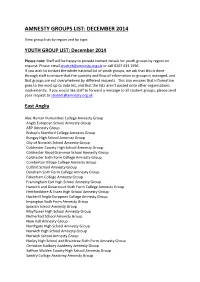

Amnesty Groups List: December 2014

AMNESTY GROUPS LIST: DECEMBER 2014 View group lists by region and by type. YOUTH GROUP LIST: December 2014 Please note: Staff will be happy to provide contact details for youth groups by region on request. Please email [email protected] or call 0207 033 1596. If you wish to contact the whole national list of youth groups, we ask that this is done through staff to ensure that the quantity and flow of information to groups is managed, and that groups are not overwhelmed by different requests. This also ensures that information goes to the most up to date list, and that the lists aren’t passed onto other organisations inadvertently. If you would like staff to forward a message to all student groups, please send your request to [email protected] East Anglia Alec Hunter Humanities College Amnesty Group Anglo European School Amnesty Group ARP Amnesty Group Bishop's Stortford College Amnesty Group Bungay High School Amnesty Group City of Norwich School Amnesty Group Colchester County High School Amnesty Group Colchester Royal Grammar School Amnesty Group Colchester Sixth Form College Amnesty Group Comberton Village College Amnesty Group Culford School Amnesty Group Dereham Sixth Form College Amnesty Group Fakenham College Amnesty Group Framingham Earl High School Amnesty Group Harwich and Dovercourt Sixth Form College Amnesty Group Hertfordshire & Essex High School Amnesty Group Hockerill Anglo-European College Amnesty Group Impington Sixth Form Amnesty Group Ipswich School Amnesty Group Mayflower High School Amnesty Group Netherhall