Nuclear Wars and Weapons Reduction for Global Security 77 Nuclear Weapons, Nuclear War and Global Security: Major Trends and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breaking Free from Nuclear Deterrence

Tenth Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future: Thursday 17 February 2011 Breaking Free from Nuclear Deterrence Commander Robert Green, Royal Navy (Retired) When David Krieger invited me to give this lecture, I discovered the illustrious list of those who had gone before me – beginning with Frank King Kelly himself in 2002. I was privileged to meet him the previous year when my wife Kate Dewes and I last visited Santa Barbara. Then it occurred to me: not only is this lecture the tenth; it is the first since Frank died last June, one day before his 96 th birthday. So I feel quite a weight on my shoulders. However, this is eased by an awareness of the uplifting qualities of the man in whose memory I have the huge honour of speaking to you this evening. As I do so, I invite you to bear in mind the following points made by Frank in his inaugural lecture: • “I believe that we human beings will triumph over all the horrible problems we may face and over the bloody history which tempts us to despair.” • Some of the scientists who brought us into the Nuclear Age made us realize that we must find ways of living in peace or confront unparalleled catastrophes. • A nun who taught him warned him he would be tested, that he would “go through trials and tribulations.” As President Truman’s speechwriter, Frank discussed the momentous decisions Truman had to make – including the one to drop the first nuclear weapons on Japan: • “When I asked him about the decision to use atom bombs on Japan, I saw anguish in his eyes. -

Andrew S. Burrows, Robert S. Norris William M

0?1' ¥t Andrew S. Burrows, Robert S. Norris William M. Arkin, and Thomas B. Cochran GREENPKACZ Damocles 28 rue des Petites Ecuries B.P. 1027 75010 Paris 6920 1 Lyon Cedex 01 Tel. (1) 47 70 46 89 TO. 78 36 93 03 no 3 - septembre 1989 no 3809 - maWaoOt 1989 Directeur de publication, Philippe Lequenne CCP lyon 3305 96 S CPPAP no en cours Directeur de publication, Palrtee Bouveret CPPAP no6701 0 Composition/Maquette : P. Bouverei Imprime sur papier blanchi sans chlore par Atelier 26 / Tel. 75 85 51 00 Depot legal S date de parution Avant-propos a ['edition fran~aise La traduction fran~aisede cette etude sur les essais nucleaires fran~aisentre dans Ie cadre d'une carnpagne mondiale de GREENPEACEpour la denuclearisation du Pacifique. Les chercheurs americains du NRDC sont parvenus a percer Ie secret qui couvre en France tout ce qui touche au nucleaire militaire. Ainsi, la France : - a effectub 172 essais nucleaires de 1960 a 1988. soil environ 10 % du nornbre total d'essais effectues depuis 1945 ; - doit effectuer 20 essais pour la rnise au point d'une t6te d'ame nuclhaire ; - effectual! 8 essais annuels depuis quelques annees et ces essais ont permis la mise au point de la bombe a neutrons des 1985 ; - a produit, depuis 1963, environ 800 tetes nuclbaires et pres de 500 sont actusllement deployees ; - a effectue pks de 110 essais souterrains a Mururoa. Les degats causes a I'atatI sont tres importants. La rbcente decision oflicielle du regroupement des essais en une seule carnpagne de tirs annuelle n'a probablement pas ete prise uniquernent pour des imperatifs econamiques ou de conjoncture internationale. -

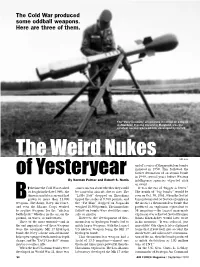

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb. -

ASROC with Systems

Naval Nuclear Weapons Chapter Eight Naval Nuclear Weapons The current program to modernize and expand U.S. deployed within the Navy (see Table 8.1) include anti- Naval forces includes a wide variety of nuclear weapons submarine warfare rockets (both surface (ASROC with systems. The build-up, according to the Department of W44) and subsurface launched (SUBROC with W55)), Defense, seeks "increased and more diversified offensive anti-air missiles (TERRIER with W45), and bombs and striking power.. increased attention to air defense . depth charges (B43, B57, and B61) used by a variety of [and] improvements in anti-submarine warfare."' The aircraft and helicopters, both carrier and land based (see plan is to build-up to a "600-ship Navy" concentrating Chapters Four and Se~en).~ on "deployable battle forces." Numerous new ships will The various nuclear weapons systems that are under be built, centered around aircraft carrier battle groups, development or are being considered for tactical naval surface groups, and attack submarines. New, more capa- nuclear warfare include: ble anti-air warfare ships, such as the TICONDEROGA (CG-47) class cruiser and BURKE (DDG-51) class  A new surface-to-air missile nuclear war- destroyers, will be deployed. New nuclear weapons and head (W81) for the STANDARD-2 missile, launching systems, as well as nuclear capable aircraft soon to enter production, carrier based forces, form a major part of the program. A long-range, land-attack nuclear armed As of March 1983, the nuclear armed ships of the U.S. Sea-Launched -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

Rencontre De L'association Henri Pézerat

RENCONTRE DE L’ASSOCIATION HENRI PÉZERAT L’antenne des irradiés de Brest Île Longue des armes nucléaires 13 au 15 Juin 2019 PREMIERS • Premier essai nucléaire effectué en 1960 « gerboise bleu » au Sahara en Algérie ESSAIS (champ de tir Reggane). NUCLÉAIRES • Puis suivent les essais souterrains (accident de Beryl en 1962) • Transferts des essais à partir de 1962 vers l'atoll de Mururoa (46 essais nucléaires FRANÇAIS EN aériens sont réalisés entre 1966 et 1974) ALGÉRIE ET EN • Entre 1975 et 1991 la France réalise 147 essais souterrains. POLYNÉSIE • Dernière campagne entre 1995 et 1996 au total 6 essais nucléaires. • Au total la France a réalisé plus de 210 essais nucléaires. L’ARME NUCLÉAIRE DEPUIS 1945 • L’arme nucléaire voit le jour avec le projet Manhattan, mené par les Etats-Unis avec la participation du Royaume-Uni et du Canada entre 1942 et 1946. • 16 juillet 1945, les scientifiques du projet Manhattan assistaient à la première explosion d’une bombe atomique, au Nouveau-Mexique, un essai organisé dans le plus grand secret. • Le 6 août1945 bombe sur Hiroshima • Le 9 aout 1945 bombe sur Nagasaki • 210 Essais nucléaires Français de 1960 à 1996 715 Union soviétique 1054 les états unis, • 2087 au niveau mondial • Conséquences : nombreuses victimes auxquelles s’ajoutent les victimes des catastrophes et accidents nucléaires • Le 2 octobre 2018, la Polynésie a déposé une plainte contre la France devant la Cour Pénale Internationale pour crimes contre l’humanité, en raison des essais nucléaires réalisés par la France pendant 30 ans. FABRICATION DES BOMBES • Depuis 1960 1000 à 2000 bombes sont sorties de Valduc . -

Dette Publique Et Dépenses D'armement : Il Faut Un Audit

Dette publique et dépenses d’armement : il faut un audit ! J C Bauduret 30/08/12 Dette publique et dépenses d’armement : il faut un audit ! Introduction. Nous n’avons qu’une planète. N’insistons pas sur ce que l’on appelle « l’état du monde », c'est-à-dire la situation de l’espèce humaine et l’état de la biosphère. En ce qui concerne la biosphère, le développement de l’espèce humaine et de son activité dans les pays les plus riches pose la question de la disparition des autres espèces, de l’épuisement des ressources, du réchauffement climatique et par conséquent de sa propre autodestruction, soit en laissant aller le cours des choses, soit par un cataclysme nucléaire. Pour 80% de la population mondiale les besoins fondamentaux – accès à la nourriture, à l’eau potable, à un logement qui ne soit pas un taudis, aux soins, à l’éducation, à l’énergie, à l’égalité hommes-femmes – ne sont pas entièrement ou même le plus souvent pas du tout satisfaits. Face à cette situation les gouvernements des pays occidentaux consacrent, pour la bonne conscience de leurs citoyens, une Aide Publique au Développement de l’ordre d’une centaine de milliards de $ par an. 1 Mais pour tuer, blesser, estropier, torturer, violer, affamer, provoquer des naissances d’enfants malformés, détruire les habitations, les installations agricoles ou industrielles, la nature, les gouvernements du monde entier dépensent 15 fois plus. Le montant des dépenses militaires mondiales s’est élevé en 2011 à 1738 milliards de $. Elles sont en augmentation chaque année depuis 13 ans, et si la crise a provoqué un infléchissement en 2011, elle n’a pas, pour autant, inversé la tendance comme cela avait été le cas pendant 10 ans jusqu’en 1998. -

Newport Paper 38

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 38 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL High Seas Buffer The Taiwan Patrol Force, 1950–1979 NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O L N L U E E G H E T I VIRIBU OR A S CT MARI VI 38 Bruce A. Elleman Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978-1-884733-95-6 is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates High Seas Buffer: The Taiwan Patrol Force, 1950–1979, by Bruce A. Elleman, as an official publication of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. -

Ministry of Defence Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym Long Title 1ACC No. 1 Air Control Centre 1SL First Sea Lord 200D Second OOD 200W Second 00W 2C Second Customer 2C (CL) Second Customer (Core Leadership) 2C (PM) Second Customer (Pivotal Management) 2CMG Customer 2 Management Group 2IC Second in Command 2Lt Second Lieutenant 2nd PUS Second Permanent Under Secretary of State 2SL Second Sea Lord 2SL/CNH Second Sea Lord Commander in Chief Naval Home Command 3GL Third Generation Language 3IC Third in Command 3PL Third Party Logistics 3PN Third Party Nationals 4C Co‐operation Co‐ordination Communication Control 4GL Fourth Generation Language A&A Alteration & Addition A&A Approval and Authorisation A&AEW Avionics And Air Electronic Warfare A&E Assurance and Evaluations A&ER Ammunition and Explosives Regulations A&F Assessment and Feedback A&RP Activity & Resource Planning A&SD Arms and Service Director A/AS Advanced/Advanced Supplementary A/D conv Analogue/ Digital Conversion A/G Air‐to‐Ground A/G/A Air Ground Air A/R As Required A/S Anti‐Submarine A/S or AS Anti Submarine A/WST Avionic/Weapons, Systems Trainer A3*G Acquisition 3‐Star Group A3I Accelerated Architecture Acquisition Initiative A3P Advanced Avionics Architectures and Packaging AA Acceptance Authority AA Active Adjunct AA Administering Authority AA Administrative Assistant AA Air Adviser AA Air Attache AA Air‐to‐Air AA Alternative Assumption AA Anti‐Aircraft AA Application Administrator AA Area Administrator AA Australian Army AAA Anti‐Aircraft Artillery AAA Automatic Anti‐Aircraft AAAD Airborne Anti‐Armour Defence Acronym -

Friends of the Royal Naval Museum

friends of the Royal Naval Museum and HMS Victory Scuttlebutt The magazine of the National Museum of the Royal Navy (Portsmouth) and the Friends ISSUE 44 SPRING 2012 By subscription or £2 Scuttlebutt The magazine of the National Museum of the Royal Navy (Portsmouth) and the Friends CONTENTS Council of the Friends 4 Chairman’s Report (Peter Wykeham-Martin) 5 New Vice Chairman (John Scivier) 6 Treasurers Report (Roger Trise) 6 Prestigious BAFM Award for ‘Scuttlebutt’ (Roger Trise) 7 News from the National Museum of the Royal Navy (Graham Dobbin) 8 HMS Victory Change of Command (Rod Strathern) 9 Steam Pinnace 199 & London Boat Show (Martin Marks) 10 Lottery Bid Success 13 Alfred John West Cinematographer 15 Peter Hollins MBE, President 199 Group (Martin Marks) 17 Skills for the Future Project (Kiri Anderson) 18 New Museum Model Series – Part 1: HMS Vanguard (Mark Brady) 20 The National Museum of the Royal Navy: 100 Years of Naval Heritage 23 at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard (Campbell McMurray) The Royal Navy and Libya (Naval Staff) 28 The Navy Campaign – “We need a Navy” (Bethany Torvell) 31 The Story of Tactical Nuclear Weapons in the Royal Navy (John Coker) 32 The Falklands War Conference at the RNM – 19 May 2012 35 Thirtieth Anniversary of the Falklands Conflict (Ken Napier) 36 HMS Queen Elizabeth - Update on Progress (BAE Systems) 38 Lost CS Forester Manuscript Found (New CS Forester book) (John Roberts) 39 Museum Wreath Workshop 39 Geoff Hunt – Leading Marine Artist (Julian Thomas) 40 Book Reviews 40 AGM – 3 May 2012 (Executive Secretary) -

The Nuclear Arms Race December 1987

The Nuclear Arms Race In Facts And Figures December 1987 I Natural Resources Defense Council 1350 New York Avenue. NW Washington. DC 20005 2027837800 I;;~:_1 '~~~~":'i• y ~. • A ~t0 J E C T OF THE N ROC NUCLEAR W E A P 0 N SO A T A 8 0 0 K This book is a set of tables summarizing the nuclear weapons arsenals of the world. It has been prepared by the authors of the Nuclear Weapons Databook series. In preparing the Databook series we have continually updated and revised our statistical data. The following tables are the product of this effort specially produced for the December Summit between President Reagan and General secretary Gorbachev. We have decided to make these data more Widely available because of the many requests, their value to other researchers, and because we are constantly seeking revisions from our readers. We have chosen a loose-leaf format to facilitate periodic revisions and to permit the user to add additional tables and figures. Detailed information about nuclear weapons is controlled by the respective governments on the basis of "national security." The following tables represent our best estimates based on a comprehensive analysis of the open literature. We believe they are the most accurate data of their kind in the open literature. We recognize, nonetheless, that these estimates can be improved, particularly regarding the nuclear arsenals of the Soviet Union and other non-u.S countries. we urge the user to alert us to any errors and to new sources of data. We would also appreciate hearing from you regarding what other tables and alternative formats would be most useful~ Thomas B. -

Fransa'nin Nükleer Gücü Ve Uluslararasi Politikaya

T.C. İSTANBUL MEDENİYET ÜNİVERSİTESİ LİSANSÜSTÜ EĞİTİM ENSTİTÜSÜ ULUSLARARASI İLİŞKİLER ANABİLİM DALI FRANSA’NIN NÜKLEER GÜCÜ VE ULUSLARARASI POLİTİKAYA ETKİLERİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi VOLKAN BABACAN ŞUBAT 2020 T.C. İSTANBUL MEDENİYET ÜNİVERSİTESİ LİSANSÜSTÜ EĞİTİM ENSTİTÜSÜ ULUSLARARASI İLİŞKİLER ANABİLİM DALI FRANSA’NIN NÜKLEER GÜCÜ VE ULUSLARARASI POLİTİKAYA ETKİLERİ Yüksek Lisans Tezi VOLKAN BABACAN DANIŞMAN PROF. DR. AHMET KAVAS ŞUBAT 2020 ÖZET FRANSA’NIN NÜKLEER GÜCÜ VE ULUSLARARASI POLİTİKAYA ETKİLERİ Babacan, Volkan Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Uluslararası İlişkiler Anabilim Dalı Danışman: Prof. Dr. Ahmet Kavas Şubat, 2020. 137 sayfa Bu tez, askeri ve ekonomik olarak Fransa’nın nükleer güç durumunun ülkenin gelişmesinde ve uluslararası politikada ne ölçüde etkili olduğunu araştırmayı amaçlamaktadır. Araştırma, Türkçe literatürde Fransa ve nükleer güç konusundaki çalışmaların sınırlı olması bakımından önem taşımaktadır. Bu doğrultuda, Fransa’nın nükleer silah kapasitesi ve nükleer enerji üretiminin gelişimini kapsamlı bir şekilde ele almaktadır. Fransa modeli, gelişmekte olan ve enerji bakımından dışa bağımlı olan ülkeler açısından ideal bir örnektir. Bununla birlikte, stratejik bir hammadde olan uranyumun temini konusunda, rezervlere sahip ülkeler ile karşılıklı kazanca dayalı bir işbirliğinin geliştirilmesi, gözetilmesi mühim bir husus olarak ortaya çıkmaktadır. Çalışmada, ikincil kaynaklardan yararlanılmış ve Uluslararası Atom Enerjisi Ajansı ve OECD Nükleer Enerji Ajansı gibi uluslararası örgütlerin hazırladıkları raporlar analiz edilerek sayısal veriler ile desteklenmiştir. Nihai olarak tez, politik, askeri ve ekonomik açıdan Fransa’nın büyük bir güç olarak varlığını sürdürmesinde nükleer teknolojideki ilerlemesinin kayda değer bir rolü olduğunu savunmaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Nükleer Silahlar, Nükleer Enerji, Fransa i ABSTRACT FRANCE’S NUCLEAR POWER STATUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Babacan, Volkan Master’s Thesis, Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof.