Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Powers and Global Contenders

CHAPTER 2 Major Powers and Global Contenders A great number of historians and political scientists share the view that international relations cannot be well understood without paying attention to those states capable of making a difference. Most diplo- matic histories are largely histories of major powers as represented in modern classics such as A. J. P. Taylor’s The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918, or Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. In political science, the main theories of international relations are essentially theories of major power behavior. The realist tradition, until recently a single paradigm in the study of international relations (Vasquez 1983), is based on the core assumptions of Morgenthau’s (1948) balance-of-power theory about major power behavior. As one leading neorealist scholar stated, “a general theory of international politics is necessarily based on the great powers” (Waltz 1979, 73). Consequently, major debates on the causes of war are centered on assumptions related to major power behavior. Past and present evidence also lends strong support for continuing interest in the major powers. Historically, the great powers partici- pated in the largest percentage of wars in the last two centuries (Wright 1942, 1:220–23; Bremer 1980, 79; Small and Singer 1982, 180). Besides wars, they also had the highest rate of involvement in international crises (Maoz 1982, 55). It is a compelling record for the modern history of warfare (since the Napoleonic Wars) that major powers have been involved in over half of all militarized disputes, including those that escalated into wars (Gochman and Maoz 1984, 596). -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Scholvin, Sören Working Paper Emerging Non-OECD Countries: Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization GIGA Working Papers, No. 128 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Scholvin, Sören (2010) : Emerging Non-OECD Countries: Global Shifts in Power and Geopolitical Regionalization, GIGA Working Papers, No. 128, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/47796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Inclusion of a paper in the Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. -

Criminal Jurisdiction Over Visiting Naval Forces Under International Law Walter F

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 Spring 3-1-1967 Criminal Jurisdiction Over Visiting Naval Forces Under International Law Walter F. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Conflict of Laws Commons, Criminal Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation Walter F. Brown, Criminal Jurisdiction Over Visiting Naval Forces Under International Law, 24 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 9 (1967), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol24/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1967] CRIMES OF VISITING NAVAL FORCES CRIMINAL JURISDICTION OVER VISITING NAVAL FORCES UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW* WALTER F. BROWNt We have here two sovereignties, deriving power from different sources, and capable of dealing with the same subject matter [a crime committed in Canada by a member of the United States armed forces] within the same territory .... Assuming for the moment that there was but one act done by the accused, interna- tional law has long recognized the possibility of the existence of two concurrent jurisdictions .... In this case, jurisdiction in the United States springs from its personal supremacy over the indi- vidual, while Canadian jurisdiction is founded upon its sovereignty in the place where the offense occurred.' JUDGE GEORGE W. -

Navigating Great Power Competition in Southeast Asia JONATHAN STROMSETH

THE NEW GEOPOLITICS APRIL 2020 ASIA BEYOND BINARY CHOICES? Navigating great power competition in Southeast Asia JONATHAN STROMSETH TRILATERAL DIALOGUE ON SOUTHEAST ASIA: ASEAN, AUSTRALIA, AND THE UNITED STATES BEYOND BINARY CHOICES? Navigating great power competition in Southeast Asia JONATHAN STROMSETH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Brookings Institution has launched a new trilateral initiative with experts from Southeast Asia, Australia, and the United States to examine regional trends in Southeast Asia in the context of escalating U.S.-China rivalry and China’s dramatic rise. The initiative not only focuses on security trends in the region, but covers economic and governance developments as well. This report summarizes the main findings and policy recommendations discussed at an inaugural trilateral dialogue, convened in Singapore in late 2019 in partnership with the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) and the Lowy Institute. A key theme running throughout the dialogue was how the region can move beyond a binary choice between the United States and China. In this connection, Southeast Asian countries could work with middle powers like Australia and Japan (admittedly a major power in economic terms) to expand middle-power agency and reduce the need for an all-or-nothing choice. Yet, there was little agreement on the feasibility of such collective action as well as doubts about whether the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has the capacity to create independent strategic space as U.S.- China competition continues to grow. Southeast Asian participants noted that Beijing has successfully leveraged its signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to expand its soft-power in the region, to the detriment of U.S. -

Breaking Free from Nuclear Deterrence

Tenth Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future: Thursday 17 February 2011 Breaking Free from Nuclear Deterrence Commander Robert Green, Royal Navy (Retired) When David Krieger invited me to give this lecture, I discovered the illustrious list of those who had gone before me – beginning with Frank King Kelly himself in 2002. I was privileged to meet him the previous year when my wife Kate Dewes and I last visited Santa Barbara. Then it occurred to me: not only is this lecture the tenth; it is the first since Frank died last June, one day before his 96 th birthday. So I feel quite a weight on my shoulders. However, this is eased by an awareness of the uplifting qualities of the man in whose memory I have the huge honour of speaking to you this evening. As I do so, I invite you to bear in mind the following points made by Frank in his inaugural lecture: • “I believe that we human beings will triumph over all the horrible problems we may face and over the bloody history which tempts us to despair.” • Some of the scientists who brought us into the Nuclear Age made us realize that we must find ways of living in peace or confront unparalleled catastrophes. • A nun who taught him warned him he would be tested, that he would “go through trials and tribulations.” As President Truman’s speechwriter, Frank discussed the momentous decisions Truman had to make – including the one to drop the first nuclear weapons on Japan: • “When I asked him about the decision to use atom bombs on Japan, I saw anguish in his eyes. -

HUMINT: a Continuing Crisis? by W

http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/humint-a-continuing-crisis HUMINT: A Continuing Crisis? by W. R. Baker Journal Article | May 8, 2017 - 8:12am A Small Wars Journal and Military Writers Guild Writing Contest Finalist Article HUMINT: A Continuing Crisis? W. R. Baker Before Vietnam completely fades from memory and its lessons learned gather even more dust, it might be worth exploring a few issues that will likely resurface again. During the latter months of the Vietnam War (1971-72), the United States was actively sending units home, turning facilities and functions over to the South Vietnamese and to U.S. forces located elsewhere before the 29 March 1973 deadline for all U.S. forces to be out of the country. In January 72, President Nixon announced that 70,000 troops would be withdrawn by 1 May 72, reducing the troop level in Vietnam to 69,000. Beginnings I was assigned in 1971 to the 571st Military Intelligence Detachment in Da Nang, the unit primarily ran Human Intelligence (HUMINT) operations throughout I Corps in northern South Vietnam. I was quickly exposed to Viet Cong (VC), North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and friendly forces’ activity in our area of interest. As such it was evident that South Vietnamese forces that had taken part in Lam Son 719 in Laos were licking their wounds - even the much touted 1st Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Division, garrisoned in Hue had been severely crippled in this failed campaign in 1971. We also dealt with other foreign country units, i.e., South Korean, who left I Corps a few months after I arrived, in addition to ARVN commanders and secret police officials. -

How Can Realism Be Utilised in an Understanding of the United States/New Zealand Relationship Over Nuclear Policy?

How can realism be utilised in an understanding of the United States/New Zealand relationship over nuclear policy? By Angela Fitzsimons A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Masters of International Relations (MIR) degree School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations Victoria University of Wellington 2013 Abstract This thesis examines the decision making process of the United States and New Zealand on the nuclear policy issue through the lens of realism and analyses the effect of realism on the ANZUS alliance. Broader questions associated with alliances, national interest, changing priorities and limits on the use of power are also treated. A single case study of the United States/ New Zealand security relationship as embodied in the ANZUS treaty will be used to evaluate the utility of realism in understanding the decision making process that led to the declaration by the United States that the treaty was in abeyance. Five significant findings emerged: firstly both New Zealand and the United States used realism in the decision making process based on national interest, Secondly; diverging national interests over the nuclear issue made the ANZUS treaty untenable. Thirdly, ethical and cultural aspects of the relationship between the two states limited the application of classical realism to understanding the bond. Fourthly, normative theory accommodates realist theory on the behaviour of states in the international environment. Finally, continued engagement between the United -

Comprehensive Examinations: a List of Historical Events, Figures, Concepts, and Terms

Comprehensive Examinations: A List of Historical Events, Figures, Concepts, and Terms Ems Telegram Gulag Archipelago Franco-Prussian War Kellogg Briand Pact Dual Alliance Non-aggression pacts Zollverein Third International Bismarck Dismissed Comintern Entente Cordiale, Russia, France Spanish Civil War Spanish-American War Popular Front Panama Canal Construction Francisco Franco Russo-Japanese War Benito Mussolini Balkan Wars Treaty of Rapallo Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Fascism Schlieffen Plan Weimar Republic Triple Entente Munich Putsch (Beer Hall Putsch) Triple Alliance Mein Kampf First Battle of the Marne Locarno Conference and Treaties Verdun Wall Street Crash (Black Monday) Lusitania Smoot Hawley Tariff Wilson declares war Hitler becomes chancellor Armistice Day National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi Treaty of Versailles Party) Senate rejects Versailles Treaty Night of the Long Knives Fourteen Points Maginot Line League of Nations Remilitarization of the Rhineland Alsace Lorraine Washington Naval Treaty David Lloyd George London Naval Treaty Georges Clemenceau Open Door Policy Ferdinand Foch Manchukuo Erich von Ludendorff Japanese occupation of Manchuria Kaiser Wilhelm (William II) Kuomintang Balfour Declaration Sun Yat-Sen Provisional Government (Russia) Chiang K’ai-Shek Petrograd Soviet Neutrality Act Bolshevik Revolution Holocaust Vladimir Lenin Adolf Hitler Leon Trotsky Joseph Goebbels Joseph Stalin Munich Conference and Agreement Feliks Dzherzhinky Neville Chamberlain Cheka Appeasement Third International -

Hauraki-Waikato

Hauraki-Waikato Published by the Parliamentary Library July 2009 Table of Contents Hauraki-Waikato: Electoral Profile......................................................................................................................3 2008 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................4 2008 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................4 2005 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................5 2005 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................5 Voter Enrolment and Turnout 2005, 2008 .......................................................................................................6 Hauraki-Waikato: People ...................................................................................................................................7 Population Summary......................................................................................................................................7 Age Groups of the Māori Descent Population .................................................................................................7 Ethnic Groups of the Māori Descent Population..............................................................................................7 -

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

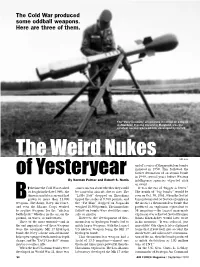

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb. -

Australia: Background and U.S

Order Code RL33010 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Updated April 20, 2006 Bruce Vaughn Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia: Background and U.S. Interests Summary The Commonwealth of Australia and the United States are close allies under the ANZUS treaty. Australia evoked the treaty to offer assistance to the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in which 22 Australians were among the dead. Australia was one of the first countries to commit troops to U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In October 2002, a terrorist attack on Western tourists in Bali, Indonesia, killed more than 200, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. A second terrorist bombing, which killed 23, including four Australians, was carried out in Bali in October 2005. The Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, was also bombed by members of Jemaah Islamiya (JI) in September 2004. The Howard Government’s strong commitment to the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq and the recently negotiated bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Australia and the United States have strengthened what were already close ties between the two long-term allies. Despite the strong strategic ties between the United States and Australia, there have been some signs that the growing economic importance of China to Australia may influence Australia’s external posture on issues such as Taiwan. Australia plays a key role in promoting regional stability in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific.