Meghan Constantinou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of the Book of Kells: Two Masters and Two Campaigns

The making of the Book of Kells: two Masters and two Campaigns Vol. I - Text and Illustrations Donncha MacGabhann PhD Thesis - 2015 Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London 1 Declaration: I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other university, and that it is entirely my own work. _________________________________ Donncha MacGabhann 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the number of individuals involved in the making of the Book of Kells. It demonstrates that only two individuals, identified as the Scribe-Artist and the Master-Artist, were involved in its creation. It also demonstrates that the script is the work of a single individual - the Scribe-Artist. More specific questions are answered regarding the working relationships between the book’s creators and the sequence of production. This thesis also demonstrates that the manuscript was created over two separate campaigns of work. The comprehensive nature of this study focuses on all aspects of the manuscript including, script, initials, display-lettering, decoration and illumination. The first part of chapter one outlines the main questions addressed in this thesis. This is followed by a summary of the main conclusions and ends with a summary of the chapter- structure. The second part of chapter one presents a literature review and the final section outlines the methodologies used in the research. Chapter two is devoted to the script and illumination of the canon tables. The resolution of a number of problematic issues within this series of tables in Kells is essential to an understanding of the creation of the manuscript and the roles played by the individuals involved. -

'321 Du I.A.P

I.A.P. Rapporten 2 .'321 DU I.A.P. Rapporten uitgegeven door I edited by Prof Dr. Guy De Boe VIOE bibliotheek 5347 11111111 ~ • 1 l~ a " a l • 1 ' W.T A l V ediled :'-, ppori\-:n 2 Ze11il< 1997 Een uitgave van het Published by the Instituul voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium Institute for the Archaeological Heritage Wetenschappelijke instelling van de Scientific Institution of the Vlaamse Gemeenschap Flemish Community Departement Leefmilieu en Infrastructuur Department of the Environment and Infrastructure Administratie Ruimtelijke Ordening, Huisvesting Administration of Town Planning, Housing en Monumenten en Landschappen and Monuments and Landscapes Doornvcld Industrie Asse 3 nr. 1 1, Bus 30 B -1731 Zcllik- Asse Tcl: (02) 463. LU3 1- 32 2 -163 13 33) fax: (02) 463.19.'1 1-.12 2-163 19 511 DTP: Arpuco. Seer.: !Vi. Lauwaert & S. Van de Voorde. ISSN 13 72-0007 ISBN 90-75230-03-6 D/1997/6024/2 02 DEATH AND BURIAL- DE WERELD VAN DE DOOD-LE MONDE DE LA MORT- TOD UND BEGRA!!NIS was organized by Gisela Grupe werd georganiseerd door Willy Dezuttere fut organisee par wurde veranstaltet von PREFACE Death and some fonn of burial are common to all milians-Universitiit, Munchcn) and Willy Dezuttere humankind and the very nature of the disposal of (City of Bruges). Unfortunately, quite a few contri human remains as well as the behavioural patterns - butors to this section did submit a text in time for social, economic, political and even environmental - inclusion in the present volume. In addition, ceme linked with this important passage in human life teries played an important part in the development and makes it a subject of direct interest to archaeology. -

{PDF EPUB} the Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. An introduction gives an overview of work on the stones, and analyses the latest thinking as to their function and meaning. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. After twenty years working in the shipping industry in Asia and America, Iain Fraser returned home in 1994 to establish The Elephant House, a caf�-restaurant in the Old Town famed for its connection with a certain fictional boy wizard. The Pictish Symbolic Stones of Scotland. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read More. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read Less. Dyce Symbol Stones. Wonder at the mysterious carvings on a pair of Pictish stones, one featuring a rare ogham inscription . The Dyce symbol stones are on display in an enclosure at the ruined kirk of St Fergus in Dyce. The older of the two, probably dating from about AD 600, is a granite symbol stone depicting a swimming beast above a cluster of symbols. -

Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross

religions Article Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross Amanda Doviak Department of History of Art, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; [email protected] Abstract: The carved figural program of the tenth-century Gosforth Cross (Cumbria) has long been considered to depict Norse mythological episodes, leaving the potential Christian iconographic import of its Crucifixion carving underexplored. The scheme is analyzed here using earlier ex- egetical texts and sculptural precedents to explain the function of the frame surrounding Christ, by demonstrating how icons were viewed and understood in Anglo-Saxon England. The frame, signifying the iconic nature of the Crucifixion image, was intended to elicit the viewer’s compunction, contemplation and, subsequently, prayer, by facilitating a collapse of time and space that assim- ilates the historical event of the Crucifixion, the viewer’s present and the Parousia. Further, the arrangement of the Gosforth Crucifixion invokes theological concerns associated with the veneration of the cross, which were expressed in contemporary liturgical ceremonies and remained relevant within the tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian context of the monument. In turn, understanding of the concerns underpinning this image enable potential Christian symbolic significances to be suggested for the remainder of the carvings on the cross-shaft, demonstrating that the iconographic program was selected with the intention of communicating, through multivalent frames of reference, the significance of Christ’s Crucifixion as the catalyst for the Second Coming. Keywords: sculpture; art history; archaeology; early medieval; Anglo-Scandinavian; Vikings; iconog- raphy Citation: Doviak, Amanda. 2021. Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross. -

The Stowe Missal

HENRY BRADSHAW SOCIETY Jounbeb in i$t T2edr of £>ur £orb 1890 for f(}e ebtfin^ of (Rare &tfurgtcaf Serfs. Vol. XXXII. ISSUED TO MEMBERS FOR THE YEAR 1906, PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN'S LANE, PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY. THE STOWE MISSAL MS. D. II. 3 IN THE LIBRARY OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY, DUBLIN. EDITED BY SIR GEORGE F. WARNER, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., late Keeper of MSS., British Museum. Vol. II. Printed Text With Introduction, Index of Liturgical Forms, and Nine Plates of the Metal Cover AND THE STOWE St. JOHN. feonfcon. *9«5- LONDON : HARRISON AND SONS, PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY, ST. MARTIN'S LANE. CONTENTS. VOL. I. The Stowe Missal : Facsimile. VOL. II. page Introduction vii Plates : — to follow lx I-VI. The Metal Cover of the Stowe Missal. VII-IX. Three pages of the Stowe St. John. The Stowe Missal: Printed Text Appendix : Translation of the Irish Treatise on the Mass 40 Index of Liturgical Forms 43 INTRODUCTION. The text here printed is that of the oldest Mass-book of the early Irish Church known to have survived, and is intended to accompany the collotype facsimile of the MS. which has already been issued in a separate volume. Incongruous as it may seem that it should take its title from an English country seat, the Stowe Missal is so called, not with any reference to its origin, but merely from the fact that for a few years it was in the library at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire, formed early in the last century by George Grenville, first Marquess of Buckingham, who died in 1813, and Richard his successor, afterwards Duke of Buckingham and Chandos. -

Kilmory Knap Chapel Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC087 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90185) Taken into State care: 1934 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KILMORY KNAP CHAPEL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KILMORY KNAP CHAPEL BRIEF DESCRIPTION Situated on the western coast of Knapdale, the medieval chapel of Kilmory lies about 4km south of Castle Sween and stands within a walled graveyard that overlooks the Sound of Jura. -

The Date and Context of the Glamis, Angus, Carved Pictish Stones Lloyd Laing*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 131 (2001), 223–239 The date and context of the Glamis, Angus, carved Pictish stones Lloyd Laing* ABSTRACT The widely accepted eighth-century dating for the Pictish relief-decorated cross-slabs known as Glamis 2 and Glamis 1 is reviewed, and an alternative ninth-century date advanced for both monuments. It is suggested that the carving on front and back of Glamis 2 was contemporaneous, and that both monuments belong to the Aberlemno School. GLAMIS 2 DESCRIPTION The Glamis 2 stone (Allen & Anderson’s scheme, 1903, pt III, 3–4) stands in front of the manse at Glamis, Angus, and its measurements — 2.76 m by 1.5 m by 0.24 m — make it one of the larger Class II slabs. It is probably a re-used Bronze Age standing stone as there appear to be some cup- marks incised on the base of the cross face. Holes have been drilled in the relatively recent past at the base of the sides, presumably for support struts. Viewed from the front (cross) face the slab is pedimented, the ornament being partly incised, partly in relief (illus 1). The cross is in shallow relief, has double hollow armpits and a ring delimited by incised double lines except in the bottom right hand corner, where the ring is absent. It is decorated with interlace, with a central interlaced roundel on the crossing. The interlace on the cross-arms and immediately above the roundel is zoomorphic. At the top of the pediment is a pair of beast heads, now very weathered, with what may be a human head between them, in low relief. -

Sueno's Stone, on the Northern Outskirts of Forres, Is a 6.5M-High Cross-Slab, the Tallest Piece of Early Historic Sculpture in Scotland

Property in Care no: 309 Designations: Scheduled Monument (90292) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2015 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SUENO’S STONE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SUENO’S STONE CONTENTS 1 Summary 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Statement of significance 2 2 Assessment of values 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Evidential values 5 2.3 Historical values 5 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 6 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 7 2.6 Natural heritage values 8 2.7 Contemporary/use values 8 3 Major gaps in understanding 10 4 Associated properties 10 5 Keywords 10 Bibliography 10 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 11 Appendix 2: Summary of archaeological investigations 12 Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction Sueno's Stone, on the northern outskirts of Forres, is a 6.5m-high cross-slab, the tallest piece of early historic sculpture in Scotland. It probably dates to the late first millennia AD.(The name Sueno, current from around 1700 and apparently in tribute to Svein Forkbeard, an 11th-century Danish king, is entirely without foundation.) In 1991 the stone was enclosed in a glass shelter to protect it from further erosion. -

Music in Scotland Before the Mid Ninth Century an Interdisciplinary

Clements, Joanna (2009) Music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century: an interdisciplinary approach. MMus(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2368/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Music in Scotland before the Mid-Ninth Century: An Interdisciplinary Approach Joanna Clements Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMus, Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2009 Abstract There are few sources for early medieval Scottish music and their interpretation is contentious. Many writers have consequently turned to Irish sources to supplement them. An examination of patterns of cultural influence in sculpture and metalwork suggests that, in addition to an Irish influence, a Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon influence and sources should be considered. Differences in the musical evidence from these groups, however, suggest a complex process of diffusion, innovation and local choice in the interaction of their musical cultures. The difficulty of predicting the course of such a process means that the observation of cultural influence in other disciplines is not on its own a useful tool in the study of music in Scotland before the mid-ninth century. -

The Illustrated Book Cover Illustrations

THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: A collection of 18 pronouncements by Buddhist sages accompanied by their pictures. n.p., n.d. Manuscript scroll folded into 42 pages, written on leaves of the bodhi tree. Chinese text, beginning with the date wu-shu of Tao kuang [·i.e. 1838 ] Wooden covers. Picture of Buddhist sage Hsu tung on front cover, accompanied by text of his pronouncement on separate leaf on back cover: "A Buddhist priest asked Buddha, 'How did the Buddha attain the most superior way?' Buddha replied, 'Protect the heart from sins; as one shines a mirror by keeping off dust, one can attain enlightenment.'" --i~ ti_ Hsu tung THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK • An Exhibit: March-May 1991 • Compiled by Alice N. Loranth Cleveland Public Library Fine Arts and Special Collections Department PREFACE The Illustrated Book exhibit was assembled to present an overview of the history of book illustration for a general audience. The plan and scope of the exhibit were developed within the confines of available exhibit space on the third floor of Main Library. Materials were selected from the holdings of Special Collections, supplemented by a few titles chosen from the collections of Fine Arts. Selection of materials was further restrained by concern for the physical well-being of very brittle or valuable items. Many rare items were omitted from the exhibit in order to safeguard them from the detrimental effects of an extended exhibit period. Book illustration is a cooperation of word and picture. At the beginning, writing itself was pictorial, as words were expressed through pictorial representation. -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

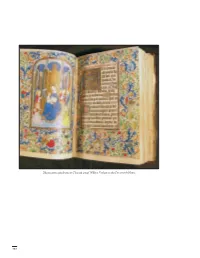

Illumination Attributed to Flemish Artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours

Illumination attributed to Flemish artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours. 132 Book Arts a Medieval Manuscripts Georgetown’s largest collection of late medieval and early renaissance documents, the Scheuch Collection, is described in the European History chapter. In addition to that collection, the library possesses nearly a score of early liturgical and theological manuscripts, including some with interesting and sometimes significant miniatures and illumina tion. Those held prior to 1970 are for the most part listed in Seymour de Ricci’s Census or its supplement, but special note should be made of the volume of spiritual opuscules in Old French (gift of John Gooch) and the altus part of the second set of the musical anthology known as the “Scots Psalter” (1586) by Thomas Wode (or Wood) of St. Andrews, possibly from the library of John Gilmary Shea. Also of note are two quite remarkable fifteenth-century manuscripts: one with texts of Bede, Hugh of St. Victor, and others (gift of Ralph A. Hamilton); the other containing works by Henry of Hesse, St. John Chrysostom, and others (gift of John H. Drury). In recent years the collection has Euclid, Elementa geometriae (1482). grown with two important additions: a truly first-rate manuscript, the Farnsworth Hours, probably illuminated in Bruges about 1465 by Willem Vrelant (gift of Mrs. Thomas M. Evans), and a previously unrecorded fifteenth-century Flemish manuscript of the Imitatio Christi in a very nearly contemporary binding (gift of the estate of Louise A. Emling). The relatively small number of complete manuscripts is supplemented, especially for teaching purposes, by a variety of leaves from individual manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the sixteenth century (in part the gifts of Bishop Michael Portier, Frederick Schneider, Mrs.