The Date and Context of the Glamis, Angus, Carved Pictish Stones Lloyd Laing*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guthrie and Rescobie Guild

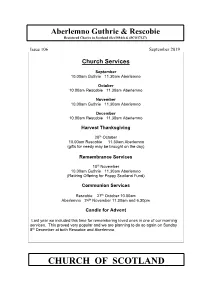

Aberlemno Guthrie & Rescobie Registered Charity in Scotland (Sco18944) & (SCO17327) Issue 106 September 2019 Church Services September 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno October 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno November 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno December 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno Harvest Thanksgiving 20th October 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno (gifts for needy may be brought on the day) Remembrance Services 10th November 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno (Retiring Offering for Poppy Scotland Fund) Communion Services Rescobie 27th October 10.00am Aberlemno 24th November 11.30am and 6.30pm Candle for Advent Last year we included this time for remembering loved ones in one of our morning services. This proved very popular and we are planning to do so again on Sunday 8th December at both Rescobie and Aberlemno. CHURCH OF SCOTLAND Guthrie August 2019 The Manse Dear Friends We are living at the moment in times of unprecedented political uncertainty. In such times it is important to hold fast to those values in life of which Paul wrote in his Letter to the Colossians; “So then, you must clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience. Be tolerant with one another and forgive one another….” In so many ways we are so fortunate to live and work in an area such as ours, aware of the circling year, of seedtime and harvest, nature and its wonder, and the value of community. We are daily reminded that amidst change and upheaval there are things that we can hold fast to, not least friendship, care and concern for others. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable Thursday 1 May 2014 1:00–1:30: Registration and Reception 1:30–1:50: Welcome and opening remarks Panel 1 Panel 2 2:00–2:30 Nicola Gordon Bowe, ‘Embroideries Liam Mac Mathúna, Douglas Hyde and out of old mythologies’: analogies between the wider world of the Gael inspiration and practice in the arts of the Celtic Revival in Dublin and Edinburgh 2:30–3:00 Sally Foster, Celtic collections and Wilson McLeod, Gaelic learners and the imperial connections: the V&A, language movement, 1870-1930 Scotland and the multiplication of plaster casts of ‘Celtic crosses’ 3:00–3:30 Elizabeth Cumming, Here Come the Rob Dunbar, Was there a Celtic Revival Celts! The Scottish National Pageant of in Canada? 1908 3:30–4:00 pm: Tea Panel 3 Panel 4 4:00–4:30 Stuart Eydmann, The harp as an Stuart Wallace, John Stuart Blackie and emblem of the Celtic Revival, with the Celtic Revival in Scotland particular reference to Scotland 4:30–5.15 John Purser, ‘The Lay of the Last Bernhard Maier, ‘Widening the Jacket’: Minstrel? Don’t count on it’: The Celtic John Stuart Blackie and Germany Revival in Scottish Classical Music 5:15–5:30: Break 5:30–6:30: Murdo Macdonald, The Art of the Scottish Celtic Revival Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery 7:00–8:30: Drinks reception and private view of A Wide New Kingdom: The Celtic Revival in Scotland, Talbot Rice Gallery. Friday 2 May 2014 10:00–11:00: Donald Meek, The Celtic Revival and the beginnings of Celtic scholarship in Scotland Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish -

Early Medieval Europe

Early Medieval Europe 1 Early Medieval Sites in Europe 2 Figure 16-2 Pair of Merovingian looped fibulae, from Jouy-le-Comte, France, mid-sixth century. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones, 4” high. Musée d’Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye. 3 Heraldic Motifs Figure 16-3 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial in Suffolk, England, ca. 625. Gold, glass, and cloisonné garnets, 7 1/2” long. British Museum, London. 4 5 Figure 16-4 Animal-head post, from the Viking ship burial, Oseberg, Norway, ca. 825. Wood, head 5” high. University Museum of National Antiquities, Oslo. 6 Figure 16-5 Wooden portal of the stave church at Urnes, Norway, ca. 1050–1070. 7 Figure 16-6 Man (symbol of Saint Matthew), folio 21 verso of the Book of Durrow, possibly from Iona, Scotland, ca. 660–680. Ink and tempera on parchment, 9 5/8” X 6 1/8”. Trinity College Library, Dublin. 8 Figure 16-1 Cross-inscribed carpet page, folio 26 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 9 Figure 16-7 Saint Matthew, folio 25 verso of the Lindisfarne Gospels, from Northumbria, England, ca. 698–721. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1 1/2” X 9 1/4”. British Library, London. 10 Figure 16-8 Chi-rho-iota (XPI) page, folio 34 recto of the Book of Kells, probably from Iona, Scotland, late eighth or early ninth century. Tempera on vellum, 1’ 1” X 9 1/2”. -

Memorandum Regarding the Fairweathers of Menmuir Parish

4- Ilh- it National Library of Scotland *B000448350* 7& A 7^ JUv+±aAJ icl^^ MEMORANDUM REGARDING THE FAIRWEATHER'S OF MENMUIR PARISH, FORFARSHIRE, AND OTHERS OF THE SURNAME, BY ALEXANDER FAIRWEATHER. EDITED, WITH NOTES, ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS, BY WILLIAM GERARD DON, M.D. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION LONDON : Dunbar & Co., 31, Marylebone Lane, W 1898. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memorandumregard1898fair CONTENTS I. Introductory. II. Of the Name in General. III. Of the Angus Fairweathers. APPENDICES. I. Kirriemuir Fairweathers. II. Intermarriage, Dons, Fairweathers, Leightons. III. Intermarriage, Leightons, Fairweathers. IV. Intermarriage, Smiths, Fairweathers. V. List of Fairweathers. VI. Fairweathers of Langhaugh. VII. Fairweathers Mill of Ballhall. VIII. Christian Names, Fairweathers. IX. Occupations, Fairweathers. — ; INTRODUCTORY. LEXANDER FAIRWEATHER, at one time Merchant in Kirriemuir, afterwards resident at Newport, Dundee, about the year 1874, wrote this Memorandum, or History ; to which he proudly affixed the following lines : " Our name and ancestry renowned or no, Free from dishonour, 'tis our pride to show." As his memorandum exists only in manuscript, and so might easily be lost, I proprose to re-edit it for printing ; with such notes, and corrections as I can furnish. Mr. Fairweather had sound literary tastes, and was a keen archaeologist and genealogist ; upon which subjects he brought to bear a considerable amount of critical acumen. The deep interest he took in everything connected with his family and surname naturally endeared him to all his kin while, unfailing geniality and lively intelligence, made him a wide circle of attached friends, ! ; 6 I only met him once, when he visited Jersey in 1876 where I happened to be quartered, with the Royal Artillery, and where he sought me out. -

1350 the Edinburgh Gazette, November 18,1870

1350 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 18,1870. Bridge over the Melgum, in place of the existing County of Forfar, in the waste-water course of the Ford and adjoining Foot Bridge. existing Crombie Reservoir of the Commissioners, 7. A portion of the said public road from Alyth at a point in the said waste-water course 55 yards, to and beyond Bridgend of Lintrathen, in the or thereabouts, measured along the said waste- aforesaid Parish of Lintrathen, and County of water course in an easterly direction from the Forfar, to be raised, such raising to commence at centre of the ridge-stone or overflow forming the a point in the said road 453 yards, or thereabouts, waste weir of the said Crombie Reservoir, which measured in an easterly direction along such road said Aqueduct, Conduit, or Line of Pipes will pass from the point where the westerly boundary of j from, in, through, or into the Parishes of Monikie the Wood known as the Craigyloch Wood joins and Carmyllie, or one of them, in the County of the said road, and thence extending in an easterly Forfar. direction 132 yards, or thereabouts, along the said 11. An Aqueduct, Conduit, or Line of Pipes, to road, where it will terminate. commence in the Parish of Carmyllie and County 8. An Aqueduct, Conduit, or Line of Pipes, to of Forfar, at an angle in the railing or fence commence in the Parish of Lintrathen and County forming the northern boundary of the land belong- of Forfar, in and out of the intended Reservoir ing to the Commissioners at the Crombie Reser- firstly before described, at a point -

Cycle Route 10

ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE STARTING POINT OathlawOathlaw N Forfar Loch Country Park AberlemnoAberlemno GRADE Moderate LENGTH PitkennedyPitkennedy 41km/25 miles APPROXIMATE TIME DubtonDubton 4-5 hours LunanheadLunanhead OS MAP RescobieRescobie 54 (Dundee & Montrose) ReswallieReswallie BalgaviesBalgavies START FORFARFORFAR MilldensMilldens GuthrieGuthrie BurnsideBurnside PitmuiesPitmuies KingsmuirKingsmuir DunnichenDunnichen LethamLetham CaldhameCaldhame IdivesIdives CraichieCraichie CYCLE ROUTE 00.71.42.1 KM © Crown copyright and database right 2021. All rights reserved. 100023404. ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE ROUTE DESCRIPTION A varied and entertaining ride that visits a number of historical sites. Starting at Forfar Loch Country Park, turn right and then take an immediate left onto Manor Street. Turn right onto Castle Street and then turn left at the T junction to Arbroath. Go straight on at the traffic lights and bear left to Brechin. Continue for 8.1km/4.9m to Aberlemno to visit the Pictish stones opposite the school. Retrace the route and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy after 100 metres. Continue for 0.9km/0.6m and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy. Turn left again after 0.1km. Continue for 2.8km/1.7m and turn left at the T junction. After 1km/0.6m, turn right. After a further 1km/0.6m, turn right at the T junction. After 4.1km/2.5m, go straight on at the crossroads crossing the B9113 to Balgavies. Turn right after 1.6km/1m. Turn right again at the T junction on to the A932. At the sign for Trumperton Tea Room, turn left. -

Angus Social Enterprise Network Directory of Members

ANGUS SOCIAL ENTERPRISE NETWORK DIRECTORY OF MEMBERS December 2019 Angus Carers Alison Myles www.anguscarers.org.uk [email protected] 01241 439157 CC 8 Grant Road, Arbroath, DD11 1JN Angus Cycle Hub Scott Francis www.anguscyclehub.co.uk [email protected] 01241 873500 CC 33 Market Place, Arbroath, DD11 1HR Angus Place Partnership Pippa Martin [email protected] C 07733 775603 Hospitalfield Trust, Arbroath, DD11 2NH Angus Upcycling Project Jeanette Gaul [email protected] CC 07594 223596 Strathmore Hall, John Street, Forfar, DD8 3EZ Angus Women’s Aid Anne Robertson Brown www.anguswomensaid.co.uk [email protected] CC 01241 439437 7 Lindsay Street, Arbroath, DD11 1RP Body Mind Soul Hub Morna Milton Webber www.bmshub.co.uk [email protected] C 07802 830631 Craigton House, Monikie, DD5 3QN Brechin Healthcare Group Dick Robertson www.brechinhealthcaregroup.org.uk [email protected] C c/o 16 Clerk Street, Brechin, DD9 6AE Bridges Coffee House Derek Marshall www.capstoneprojects.org.uk/bridges-coffee- [email protected] house 07950 026736 CC 42 Bank Street, Kirriemuir, DD8 4BG Caledonian Railway Jon Gill www.caledonianrailway.com [email protected] CC 07920 065579 The Station, Park Road, Brechin, DD9 7AF Care About Angus Mark Rogers www.careaboutangus.org.uk [email protected] CC 01241 797777 5 – 7 The Cross, Forfar, DD8 1BB Coaching in Communities Dawn Mullady See Facebook [email protected] A 07921 450172 1A Academy Street, Forfar, DD8 2HA -

{PDF EPUB} the Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Pictish Symbol Stones of Scotland by Iain Fraser ISBN 13: 9781902419534. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. An introduction gives an overview of work on the stones, and analyses the latest thinking as to their function and meaning. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. After twenty years working in the shipping industry in Asia and America, Iain Fraser returned home in 1994 to establish The Elephant House, a caf�-restaurant in the Old Town famed for its connection with a certain fictional boy wizard. The Pictish Symbolic Stones of Scotland. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read More. This is a revised and expanded version of the RCAHMS publication originally entitled Pictish Symbol Stones - a Handlist . It publishes the complete known corpus of Pictish symbol stones, including descriptions, photos and professional archaeological drawings of each. Read Less. Dyce Symbol Stones. Wonder at the mysterious carvings on a pair of Pictish stones, one featuring a rare ogham inscription . The Dyce symbol stones are on display in an enclosure at the ruined kirk of St Fergus in Dyce. The older of the two, probably dating from about AD 600, is a granite symbol stone depicting a swimming beast above a cluster of symbols. -

Angus, Scotland Fiche and Film

Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1841 Census Index 1891 Census Index Parish Registers 1851 Census Directories Probate Records 1861 Census Maps Sasine Records 1861 Census Indexes Monumental Inscriptions Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Non-Conformist Records Wills 1841 CENSUS INDEXES Index to the County of Angus including the Burgh of Dundee Fiche ANS 1C-4C 1851 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1851 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Auchterhouse (273) East Scotson Greenford Balbuchly Mid-Lioch East Lioch West Lioch Upper Templeton Lower Templeton Kirkton BonninGton Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Whitefauld East Mains Burnhead Gateside Newton West Mains Eastfields East Adamston Bronley Parish of Barry (274) Film 1851 Census ANS1 Parish of Brechin (275) Little Brechin Trinity Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Royal Burgh of Brechin Brechin Lock-Up House for the City of Brechin Brechin Jail Parish of Carmyllie (276) CarneGie Stichen Mosside Faulds Graystone Goat Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Dislyawn Milton Redford Milton of Conan Dunning Parish of Montrose (312) Film 1851 Census ANS 2 1861 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Aberlemno (269) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Airlie (270) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Arbirlot (271) Film ANS 269-273 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 12 Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Abroath (272) Parliamentary Burgh of Abroath Abroath Quoad Sacra Parish of Alley - Arbroath St. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen.