The Battle of Dunnichen, AD 685

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guthrie and Rescobie Guild

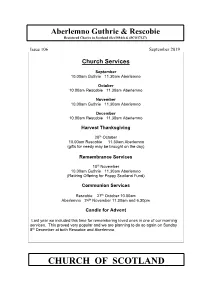

Aberlemno Guthrie & Rescobie Registered Charity in Scotland (Sco18944) & (SCO17327) Issue 106 September 2019 Church Services September 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno October 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno November 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno December 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno Harvest Thanksgiving 20th October 10.00am Rescobie 11.30am Aberlemno (gifts for needy may be brought on the day) Remembrance Services 10th November 10.00am Guthrie 11.30am Aberlemno (Retiring Offering for Poppy Scotland Fund) Communion Services Rescobie 27th October 10.00am Aberlemno 24th November 11.30am and 6.30pm Candle for Advent Last year we included this time for remembering loved ones in one of our morning services. This proved very popular and we are planning to do so again on Sunday 8th December at both Rescobie and Aberlemno. CHURCH OF SCOTLAND Guthrie August 2019 The Manse Dear Friends We are living at the moment in times of unprecedented political uncertainty. In such times it is important to hold fast to those values in life of which Paul wrote in his Letter to the Colossians; “So then, you must clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience. Be tolerant with one another and forgive one another….” In so many ways we are so fortunate to live and work in an area such as ours, aware of the circling year, of seedtime and harvest, nature and its wonder, and the value of community. We are daily reminded that amidst change and upheaval there are things that we can hold fast to, not least friendship, care and concern for others. -

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Report No 170/11

Agenda Item No Report No. 170/11 ANGUS COUNCIL INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES COMMITTEE 1 MARCH 2011 ANGUS LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN RESPONSE FROM INITIAL CONSULTATION AND KEY AGENCY ENGAGEMENT REPORT BY DIRECTOR OF INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES Abstract: This report provides Members with an overview of the response to the recent awareness raising and initial consultation exercise and outlines the next steps towards preparation of a Main Issues Report. 1 RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Committee note the range and scale of the response to the recent awareness raising and initial consultation exercise and how this will be progressed to produce a Local Development Plan. 2 INTRODUCTION 2.1 The Infrastructure Services Committee at their meeting of 24 August 2010 approved the commencement of the preparation of the first Angus Local Development Plan (LDP). The Committee also approved arrangements for initial awareness raising and stakeholder and community engagement, including the raising of issues and potential development sites for consideration during preparation of the Angus LDP Main Issues Report (Report No. 582/10 refers). 2.2 This report provides an overview of responses to initial consultation from those with an interest in the Angus LDP (including Key Agencies, landowners, developers, agents, community groups and the general public). 3 AWARENESS RAISING & INITIAL CONSULTATION Awareness Raising 3.1 Following Committee approval to commence the preparation of the Angus LDP Planning & Transport undertook to raise awareness of commencement of -

Ancient Origins of Lordship

THE ANCIENT ORIGINS OF THE LORDSHIP OF BOWLAND Speculation on Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norse and Brythonic roots William Bowland The standard history of the lordship of Bowland begins with Domesday. Roger de Poitou, younger son of one of William the Conqueror’s closest associates, Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, is recorded in 1086 as tenant-in-chief of the thirteen manors of Bowland: Gretlintone (Grindleton, then caput manor), Slatebourne (Slaidburn), Neutone (Newton), Bradeforde (West Bradford), Widitun (Waddington), Radun (Radholme), Bogeuurde (Barge Ford), Mitune (Great Mitton), Esingtune (Lower Easington), Sotelie (Sawley?), Hamereton (Hammerton), Badresbi (Battersby/Dunnow), Baschelf (Bashall Eaves). William Rufus It was from these holdings that the Forest and Liberty of Bowland emerged sometime after 1087. Further lands were granted to Poitou by William Rufus, either to reward him for his role in defeating the army of Scots king Malcolm III in 1091-2 or possibly as a consequence of the confiscation of lands from Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria in 1095. 1 As a result, by the first decade of the twelfth century, the Forest and Liberty of Bowland, along with the adjacent fee of Blackburnshire and holdings in Hornby and Amounderness, had been brought together to form the basis of what became known as the Honor of Clitheroe. Over the next two centuries, the lordship of Bowland followed the same descent as the Honor, ultimately reverting to the Crown in 1399. This account is one familiar to students of Bowland history. However, research into the pattern of land holdings prior to the Norman Conquest is now beginning to uncover origins for the lordship that predate Poitou’s lordship by many centuries. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-ROUSE. MA.Ren 1

2646 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-ROUSE. MA.Ren 1, HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Cherokees to sue for their interest in certain moneys of the tribe from which they were excluded. WEDNESDAY, March 1, 1899. The message also announced that the Senate had passed with amendments the bill (H. R. 9335) granting t-0 the Muscle Shoals The House met at 11 o'clock a. m. Prayer by the Chaplain, Rev. Power Company right to erect and construct canal and power HENRY N. COUDEN. stations at Muscle Shoals, Ala.; in which the concurrence of the The Journal of the proceedings of yesterday was read and ap House of Representatives was requested. proved. MESSA.GE FROM THE SENA.TE. SUNDRY CIVIL APPROPRIATION BILL, A message from the Senate, by Mr. PLATT, one of its clerks, Mr. CANNON. Mr. Speaker, I ask unanimous consent that announced that the Senate had passed with amendments a bill of the House nonconcur in all of the amendments of the Senate to the the following title; in which the concurrence of the House was sundry civil appropriation bill, ask for a committee of confer requested: ence on the disagreeing votes of the two Houses, and have the bill H. R. 12008. An act making appropriations for sundry civil ex printed with the Senate amendments numbered. penses of the Government for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1900, The SPEAKER. Is there objection to the request of the gen and for other purposes. tleman from Illinois? The message also announced that the Senate had passed without There was no objection. amendment·bills of the following titles: The SPEAKER appointed as conferees on the part of the House H. -

Cycle Route 10

ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE STARTING POINT OathlawOathlaw N Forfar Loch Country Park AberlemnoAberlemno GRADE Moderate LENGTH PitkennedyPitkennedy 41km/25 miles APPROXIMATE TIME DubtonDubton 4-5 hours LunanheadLunanhead OS MAP RescobieRescobie 54 (Dundee & Montrose) ReswallieReswallie BalgaviesBalgavies START FORFARFORFAR MilldensMilldens GuthrieGuthrie BurnsideBurnside PitmuiesPitmuies KingsmuirKingsmuir DunnichenDunnichen LethamLetham CaldhameCaldhame IdivesIdives CraichieCraichie CYCLE ROUTE 00.71.42.1 KM © Crown copyright and database right 2021. All rights reserved. 100023404. ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE ROUTE DESCRIPTION A varied and entertaining ride that visits a number of historical sites. Starting at Forfar Loch Country Park, turn right and then take an immediate left onto Manor Street. Turn right onto Castle Street and then turn left at the T junction to Arbroath. Go straight on at the traffic lights and bear left to Brechin. Continue for 8.1km/4.9m to Aberlemno to visit the Pictish stones opposite the school. Retrace the route and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy after 100 metres. Continue for 0.9km/0.6m and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy. Turn left again after 0.1km. Continue for 2.8km/1.7m and turn left at the T junction. After 1km/0.6m, turn right. After a further 1km/0.6m, turn right at the T junction. After 4.1km/2.5m, go straight on at the crossroads crossing the B9113 to Balgavies. Turn right after 1.6km/1m. Turn right again at the T junction on to the A932. At the sign for Trumperton Tea Room, turn left. -

Forfar G Letham G Arbroath

Timetable valid from 30th March 2015. Up to date timetables are available from our website, if you have found this through a search engine please visit stagecoachbus.com to ensure it is the correct version. Forfar G Letham G Arbroath (showing connections from Kirriemuir) 27 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 27 27C 27A 27 27 27 27 27 27 27A 27B 27 27 27 27 27 27 27 G Col Col NCol NSch Sch MTh Fri Kirriemuir Bank Street 0622 — 0740 0740 0835 0946 1246 1346 1446 — — — — 1825 1900 2115 2225 2225 Padanaram opp St Ninians Road 0629 — 0747 0747 0843 0953 1253 1353 1453 — — — — 1832 1907 2122 2232 2232 Orchardbank opp council offi ces — — 0752 0752 | | | | | — — — — | | | | | Forfar Academy — — | | | M M M M — 1555 — — | | | | | Forfar East High Street arr — — | | | 1003 1303 1403 1503 — | — — | | | | | Forfar New Road opp Asda — — M M M 1001 1301 1401 1501 1546 | 1646 — M M M M M Forfar East High Street arr 0638 — 0757 0757 0857 1002 1302 1402 1502 1547 | 1647 — 1841 1916 2131 2241 2241 Forfar East High Street dep 0647 0800 0805 0805 0905 1005 1305 1405 1505 1550 | 1655 1745 1845 1945 2155 2255 2255 Forfar Arbroath Rd opp Nursery 0649 0802 | 0807 0907 1007 1307 1407 1507 | | 1657 1747 1847 1947 2157 2257 2257 Forfar Restenneth Drive 0650 | M 0808 0908 1008 1308 1408 1508 M M 1658 1748 1848 1948 2158 2258 2258 Kingsmuir old school 0653 | 0809 0811 0911 1011 1311 1411 1511 1554 1604 1701 1751 1851 1951 2201 2301 2301 Dunnichen M | M M M M M M M M 1607 M M M M M M M Craichie village 0658 | 0814 0816 0916 1016 1316 1416 1516 1559 | 1706 1756 1856 1956 -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Introduction to the Abercorn Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION ABERCORN PAPERS November 2007 Abercorn Papers (D623) Table of Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................2 Family history................................................................................................................3 Title deeds and leases..................................................................................................5 Irish estate papers ........................................................................................................8 Irish estate and related correspondence.....................................................................11 Scottish papers (other than title deeds) ......................................................................14 English estate papers (other than title deeds).............................................................17 Miscellaneous, mainly seventeenth-century, family papers ........................................19 Correspondence and papers of the 6th Earl of Abercorn............................................20 Correspondence and papers of the Hon. Charles Hamilton........................................21 Papers and correspondence of Capt. the Hon. John Hamilton, R.N., his widow and their son, John James, the future 1st Marquess of Abercorn....................22 Political correspondence of the 1st Marquess of Abercorn.........................................23 Political and personal correspondence of the 1st Duke of Abercorn...........................26 -

Invisible Ink: the Recovery and Analysis of a Lost Text from the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1)

Invisible Ink: The Recovery and Analysis of a Lost Text from the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1) Introduction In a previous volume of this journal we surveyed a selection of the images and texts which can be recovered from the pages of the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1) when the manuscript and high-resolution images of it were subject to a series of digital analyses.1 The present discussion focuses on one page of the manuscript, fol. 40v. Although the space was once filled with text dating to just after the compilation of the Black Book, it was obliterated at some stage in the manuscript’s ‘cleansing’.2 In fact, it is possible that this page was erased more than once, and that the shadow of a large initial B which we initially believed to be the start of a second poem is instead evidence of palimpsesting.3 The particular exuberance of the erasure in the bottom quarter of the page may support this view. As it stands, faint traces of lines of text can be seen on the page in its original, digitised and facsimile forms;4 in fact, of these Gwenogvryn Evans’s facsimile preserves the most detail.5 Minims and the occasional complete letter are discernible, but on the whole the page is illegible. Nevertheless, enough of the text of this page is visible for it to feel tantalizingly recoverable, and the purpose of what follows is first to show what can be recovered using modern techniques 1 Williams, ‘The Black Book of Carmarthen: Minding the Gaps’, National Library of Wales Journal 36 (2017), 357–410. -

Angus, Scotland Fiche and Film

Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1841 Census Index 1891 Census Index Parish Registers 1851 Census Directories Probate Records 1861 Census Maps Sasine Records 1861 Census Indexes Monumental Inscriptions Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Non-Conformist Records Wills 1841 CENSUS INDEXES Index to the County of Angus including the Burgh of Dundee Fiche ANS 1C-4C 1851 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1851 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Auchterhouse (273) East Scotson Greenford Balbuchly Mid-Lioch East Lioch West Lioch Upper Templeton Lower Templeton Kirkton BonninGton Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Whitefauld East Mains Burnhead Gateside Newton West Mains Eastfields East Adamston Bronley Parish of Barry (274) Film 1851 Census ANS1 Parish of Brechin (275) Little Brechin Trinity Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Royal Burgh of Brechin Brechin Lock-Up House for the City of Brechin Brechin Jail Parish of Carmyllie (276) CarneGie Stichen Mosside Faulds Graystone Goat Film 1851 Census ANS 1 Dislyawn Milton Redford Milton of Conan Dunning Parish of Montrose (312) Film 1851 Census ANS 2 1861 CENSUS Angus Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Parish of Aberlemno (269) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Airlie (270) Film ANS 269-273 Parish of Arbirlot (271) Film ANS 269-273 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 12 Angus Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Abroath (272) Parliamentary Burgh of Abroath Abroath Quoad Sacra Parish of Alley - Arbroath St.