Annual Report 2017 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krautscheid Wird CDU-Generalsekretär

politik & �����������������Ausgabe���������� Nr. 273 � kommunikation politikszene 2.3. – 8.3.2010 �������������� Westerwelle holt Steiner Bundesaußenminister Guido Westerwelle will laut dem Nachrichtenmagazin „Spiegel“ Michael Steiner ����������������������������������������������(60) ins Auswärtige Amt nach Berlin holen. Dem zufolge soll Steiner, derzeit deutscher Botschafter in Rom, neuer Afghanistan-Beauftragter werden. Steiner, der früher außenpolitischer Berater des ehemali- �����������Bernd��������������������������������������������������� Mützelburg gen Bundeskanzlers Gerhard Schröders war, würde auf Bernd��������������������� Mützelburg folgen. �������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������2002 bis 2003 2003 bis 2007 2007 bis 2010�������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������Chef der Mission der Vereinten Vertreter der Bundesrepublik Botschafter der Bundesrepublik� ����������� �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������Nationen im Kosovo, UNMIK Deutschland bei den Vereinten Deutschland in Rom ����������������������������������������������������������Nationen in��������������������� Genf � Michael Steiner ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������Eggelmeyer leitet neue Abteilung im BMZ � ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: a Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-27-2014 Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives Murat Altuglu Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14071144 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Altuglu, Murat, "Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1565. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1565 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ELECTORAL RULES AND ELITE RECRUITMENT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE BUNDESTAG AND THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Murat Altuglu 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Murat Altuglu, and entitled Electoral Rules and Elite Recruitment: A Comparative Analysis of the Bundestag and the U.S. House of Representatives, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual -

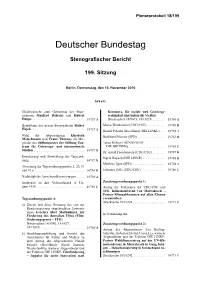

Plenarprotokoll 17/30

Plenarprotokoll 17/30 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 30. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 17. März 2010 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt I (Fortsetzung): Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) (CDU/CSU) 2744 C a) Zweite Beratung des von der Bundesregie- Dr. Lukrezia Jochimsen (DIE LINKE) . 2745 C rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Geset- Reiner Deutschmann (FDP) . 2746 B zes über die Feststellung des Bundes- haushaltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ 2010 (Haushaltsgesetz 2010) DIE GRÜNEN) . 2747 C (Drucksachen 17/200, 17/201) . 2705 A Siegmund Ehrmann (SPD) . 2748 C b) Beschlussempfehlung des Haushaltsaus- schusses zu der Unterrichtung durch die Namentliche Abstimmung . Bundesregierung: Finanzplan des Bundes 2749 B 2009 bis 2013 (Drucksachen 16/13601, 17/626) . 2705 B Ergebnis . 2752 C 9 Einzelplan 04 10 Einzelplan 05 Bundeskanzlerin und Bundeskanzleramt Auswärtiges Amt (Drucksachen 17/604, 17/623) . 2705 B (Drucksachen 17/605, 17/623) . 2749 C Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) . 2705 D Klaus Brandner (SPD) . 2749 C Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin . 2711 A Dr. Guido Westerwelle, Bundesminister AA . Dr. Gregor Gysi (DIE LINKE) . 2720 A 2754 B Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) . 2756 C Birgit Homburger (FDP) . 2725 A Herbert Frankenhauser (CDU/CSU) . 2758 B Renate Künast (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 2730 B Sven-Christian Kindler (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 2759 A Volker Beck (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 2734 C Klaus Brandner (SPD) . 2759 B Birgit Homburger (FDP) . 2734 D Kerstin Müller (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 2761 A Volker Kauder (CDU/CSU) . 2735 B Dr. h. c. Jürgen Koppelin (FDP) . 2761 C Dr. Barbara Hendricks (SPD) . 2736 B Dr. Rainer Stinner (FDP) . 2763 D Bernd Scheelen (SPD) . -

Bund Entlastet Kommunen Und Stärkt Den Ausbau Der

Landesgruppe Nordrhein-Westfalen Nr. 21/04.12.2014 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, Bund entlastet Kommunen und stärkt liebe Freunde, den Ausbau der Kindertagesbetreuung nach Vorlage des Gesetz- entwurfs zu Änderungen im Wasserhaushaltsgesetz be- Bereits in den vergangenen Legisla- züglich Fracking ist die un- turperioden hat der Bund Länder konventionelle Erdgasförde- und Kommunen umfassend entlas- rung erneut in den Mittel- tet. So wurde etwa mit der vollstän- punkt der Diskussion ge- rückt. digen Übernahme der laufenden In den beiden zurückliegenden Jahren habe ich Nettoausgaben für die Grundsiche- öffentlich stets meine klar ablehnende Haltung rung im Alter und bei Erwerbsmin- zu Fracking erklärt. Solange Restrisiken für derung bereits ein wesentlicher Bei- Mensch und Natur verbleiben, halte ich diese Technologie für nicht vertretbar. Es bestehen trag zur Verbesserung der kommu- zudem enorme Wissenslücken. Im vergangenen nalen Finanzsituation geleistet. Im Jahr konnte ich mit meinen CDU-Kollegen aus Jahr 2014 führt die letzte Stufe der Anhebung der Bundesbeteiligung von dem Münsterland, weiteren westfälischen 75 Prozent auf 100 Prozent zu einer Entlastung in Höhe von voraussicht- Kollegen und der bayerischen CSU darauf hinwirken, dass es erst gar nicht zur Vorlage lich rund 1,6 Milliarden Euro. Die Entlastung der Kommunen zählt auch eines entsprechenden Gesetzentwurfes kam. weiterhin zu den prioritären Maßnahmen des Bundes. Im Rahmen der Dem jetzt von den zuständigen Bundesminis- Verabschiedung des Bundesteilhabegesetzes sollen die Kommunen im tern Sigmar Gabriel und Dr. Barbara Hendricks Umfang von 5 Milliarden Euro jährlich von der Eingliederungshilfe entlas- vorliegenden Gesetzentwurf kann ich in dieser Form nur ablehnen. Ich habe sozusagen an tet werden. Bereits im Vorgriff darauf wird der Bund in den Jahren 2015 allen Infoveranstaltungen der letzten zwei Jahre bis 2017 die Kommunen in Höhe von 1 Milliarde Euro pro Jahr entlasten. -

16. Bundesversammlung Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12

16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12. Februar 2017 Gemeinsame Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages und des Bundesrates anlässlich der Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Berlin, 22. März 2017 Inhalt 4 16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 6 Rede des Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 16 Konstituierung der 16. Bundesversammlung 28 Bekanntgabe des Wahlergebnisses 34 Rede von Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 40 Gemeinsame Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages und des Bundesrates anlässlich der Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 42 Programm 44 Begrüßung durch den Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 48 Ansprache der Präsidentin des Bundesrates, Malu Dreyer 54 Ansprache des Bundespräsidenten a. D., Joachim Gauck 62 Eidesleistung des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 64 Ansprache des Bundespräsidenten Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier 16. Bundesversammlung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Berlin, 12. Februar 2017 Nehmen Sie bitte Platz. Sehr geehrter Herr Bundespräsident! Exzellenzen! Meine Damen und Herren! Ich begrüße Sie alle, die Mitglieder und Gäste, herzlich zur 16. Bundesversammlung im Reichstagsgebäude in Berlin, dem Sitz des Deutschen Bundestages. Ich freue mich über die Anwesenheit unseres früheren Bundesprä- sidenten Christian Wulff und des langjährigen österreichischen Bundespräsidenten Heinz Fischer. Seien Sie uns herzlich willkommen! Beifall Meine Damen und Herren, der 12. Februar ist in der Demokratiegeschichte unseres Landes kein auffälliger, aber eben auch kein beliebiger Tag. Heute vor genau 150 Jahren, am 12. Februar 1867, wurde ein Reichstag gewählt, nach einem in Deutschland nördlich der Mainlinie damals in jeder Hinsicht revolu- tionären, nämlich dem allgemeinen, gleichen Rede des Präsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert 6 und direkten Wahlrecht. Der Urnengang zum konstituierenden Reichstag des Norddeut- schen Bundes stützte sich auf Vorarbeiten der bekannte. -

Afd Vor Dem Großen Sprung

: rer . 3 nde rt S wa ie Zu llab ko rlin Be Das Ostpreußenblatt Einzelverkaufspreis: 2,50 Euro Nr. 37 – 13. September 2014 C5524 - PVST. Gebühr bezahlt U NABHÄNGIGE W OCHENZEITUNG FÜR D EUTSCHLAND DIES E WOCH E JAN HEITMANN : Total verbockt Aktuell er als Zuwanderer dem Warnung vor den eigenen WStaat durch die illegale Be - Leuten setzung eines öffentlichen Plat - Ex-US-Geheimdienstler zes ein „Einigungspapier“ schreiben der Kanzlerin 2 abringt, erhält dadurch weder einen Aufenthaltstitel noch eine Duldung. Diese Entscheidung Preuße n/ Berlin des Berliner Verwaltungsgerichts ist zu begrüßen, macht sie doch Zuwanderer: Berlin deutlich, dass sich der Staat letzt - kollabiert endlich nicht nötigen lässt. Das Erstaufnahme wegen des Urteil hat aber einen negativen Ansturms geschlossen 3 Beigeschmack, denn wieder ein - mal musste die Justiz richten, was die Politik total verbockt Hintergrund hat. Richtig wäre es gewesen, wenn der Senat den Platz sofort Kränkelnd, aber nicht durch die Polizei hätte räumen schwach und die nicht asylberechtigten China als Gewinner der Personen abschieben lassen, Ukraine-Krise 4 statt dort über lange Zeit einen rechtsfreien Raum zu dulden. Vor der EZB in Frankfurt: Tausende AfD-Anhänger demonstrieren gegen die Europolitik Bild: action press Die mit den Besetzern erzielte Deutschland Einigung kommt einer Kapitula - tion des Rechtsstaates gleich. Sparen à la Schäuble Den ehemaligen Oranien - Bundesbehörden und AfD vor dem großen Sprung platz-Besetzern, die durch die Ei - Infrastruktur müssen nigung nur vermeintlich Rechte wegen Sparvorgaben leiden 5 erworben haben, stehen nun der Die Landtagswahlen diesen Sonntag werden Deutschland verändern Rechtsweg und die Anrufung von Petitionsausschüssen sowie Ausland Der Siegeszug der AfD erscheint nach dem Bruch mit der SPD oder men-Partei, hieß es lange. -

Cherchez La Citoyenne! Bürger- Und Zivilgesellschaft Aus Geschlechterpolitischer Perspektive

Cherchez la Citoyenne! Bürger- und Zivilgesellschaft aus geschlechterpolitischer Perspektive FEMINA POLITICA 2 | 2007 Editorial INhalt EditorIAL ..................................................................................................... 7 SChWErPUNKT: Cherchez la Citoyenne! Bürger- und Zivilgesellschaft aus geschlechterpolitischer Perspektive ........9 EVa Maria HiNtErHUBEr. GaBriElE WildE Cherchez la Citoyenne! Eine Einführung in die Diskussion um „Bürger- und Zivilgesellschaft“ aus geschlechterpolitischer Perspektive ..................... 9 EVa SÄNGEr Umkämpfte Räume. Zur Funktion von Öffentlichkeit in Theorien der Zivilgesellschaft .................................................................................................... 18 adElHEid BiESECKEr. ClaUdia VoN BraUNMÜHl. CHriSTA WiCHtEriCH. UTA VoN WiNtErFEld Die Privatisierung des Politischen. Zu den Auswirkungen der doppelten Privatisierung .............................................................................................. 28 CHriStiNa StECKEr Ambivalenz der Differenz. Frauen zwischen bürgerschaftlichem Engagement, Erwerbsarbeit und Sozialstaat ..................................................................................... 41 GiSEla NOTZ „Das Museum greift gern auf die einsatzfreudigen Damen zurück.“ Bürgerschaftliches Engagement im Bereich von Kultur und Soziokultur ................... 53 aNNEttE ZiMMEr. HolGEr KriMMEr Does gender matter? Haupt- und ehrenamtliche Führungskräfte gemeinnütziger Organisationen ................................................................................. -

Abgeordnete Bundestag Ergebnisse

Recherche vom 27. September 2013 Abgeordnete mit Migrationshintergrund im 18. Deutschen Bundestag Recherche wurde am 15. Oktober 2013 aktualisiert WWW.MEDIENDIENST-INTEGRATION.DE Bundestagskandidaten mit Migrationshintergrund VIELFALT IM DEUTSCHEN BUNDESTAG ERGEBNISSE für die 18. Wahlperiode Im neuen Bundestag finden sich 37 Parlamentarier mit eigener Migrationserfahrung oder mindestens einem Elternteil, das eingewandert ist. Im Verhältnis zu den insgesamt 631 Sitzen im Parlament stammen somit 5,9 Prozent der Abgeordneten aus Einwandererfamilien. In der gesamten Bevölkerung liegt ihr Anteil mehr als dreimal so hoch, bei rund 19 Prozent. In der vorigen Legislaturperiode saßen im Bundestag noch 21 Abgeordnete aus den verschiedenen Parteien, denen statistisch ein Migrationshintergrund zugesprochen werden konnte. Im Vergleich zu den 622 Abgeordneten lag ihr Anteil damals lediglich bei 3,4 Prozent. Die Anzahl der Parlamentarier mit familiären Bezügen in die Türkei ist von fünf auf elf gestiegen. Mit Cemile Giousouf ist erstmals auch in der CDU eine Abgeordnete mit türkischen Wurzeln im Bundestag vertreten, ebenso wie erstmals zwei afrodeutsche Politiker im Parlament sitzen (Karamba Diaby, SPD und Charles M. Huber, CDU). Gemessen an der Anzahl ihrer Sitze im Parlament verzeichnen die LInken mit 12,5 Prozent und die Grünen mit 11,1 Prozent den höchsten Anteil von Abgeordneten mit Migrationshintergrund. Die SPD ist mit 13 Parlamentariern in reellen Zahlen Spitzenreiter, liegt jedoch im Verhältnis zur Gesamtzahl ihrer Abgeordneten (193) mit 6,7 -

Adressliste EU Betrb

ANSCHRIFTEN für die Mailing-Aktion in Sachen „EU-Betriebsbeschränkungsverordnung“ Präsident des Europäischen Parlaments (vorrausichtlich ab dem 18.01.2012) Herr Martin Schulz, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Deutsche Mitglieder im Verkehrausschuss des Europäischen Parlaments: Herr Dieter-Lebrecht Koch, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Herr Michael Cramer, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Herr Ismail Ertrug, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Herr Knut Fleckenstein, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Herrn Werner Kuhn, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Frau Gesine Meissner, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Herr Thomas Ulmer, MdEP Europäisches Parlament [email protected] Bundesminister für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung Herr Dr. Peter Ramsauer, MdB [email protected] Landtagsabgeordnete Mainz Wahlkreis 1: Frau Ulla Brede-Hoffmann [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Herr Gerd Schreiner [email protected] Herr Gunther Heinisch [email protected] [email protected] Herr Daniel Köbler [email protected] [email protected] Mainz Wahlkreis 2: Herr Wolfgang Reichel [email protected] [email protected] Frau Doris Ahnen [email protected] [email protected] Herr Dr. Rahim Schmidt [email protected] [email protected] Bundestagsabgeordnete: Frau Ute Granold [email protected] [email protected] Herr Michael Hartmann [email protected] [email protected] Herr Reiner Brüderle [email protected] Frau Tabea Rößner [email protected] [email protected] Europaparlamentarier aus Rheinland-Pfalz Frau Jutta Steinruck [email protected] Herr Kurt Lechner [email protected] Herr Dr. -

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17Th Session of the German Bundestag

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag Stephen Colby Woods University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Stephen Colby, "Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag" (2014). Honors Theses. 875. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/875 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JA, ICH WILL: FRAMING THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE DEBATE IN THE 17TH SESSION OF THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG 2014 By S. Colby Woods A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College University of Mississippi University of Mississippi May 2014 Approved: __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Ross Haenfler __________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen __________________________ Reader: Dr. Alice Cooper © 2014 Stephen Colby Woods ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION I would first like to thank the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for fostering my academic growth and development over the past four years. I want to express my sincerest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr.