VIRGIL and the MONUMENTS (Lecture Given to a Joint Meeting Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dawn in Erewhon"

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences December 2007 Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Patrick Dillon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Dillon, Patrick, "Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon"" 10 December 2007. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23. Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Abstract In "The Dawn in Erewhon", the concluding novella of Tatlin!, Guy Davenport explores the myth of Orpheus in the context of two storylines: Adriaan van Hovendaal, a thinly veiled version of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an updated retelling of Samuel Butler's utopian novel Erewhon. Davenport tells the story in a disjunctive style and uses the Orpheus myth as a symbol to refer to a creative sensibility that has been lost in modern technological civilization but is recoverable through art. Keywords Charles Bernstein, Bernstein, Charles, English, Guy Davenport, Davenport, Orpheus, Tatlin, Dawn in Erewhon, Erewhon, ludite, luditism Comments Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 Dimensions of Erewhon The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport’s “The Dawn in Erewhon” Patrick Dillon Introduction: The Assemblage Style Although Tatlin! is Guy Davenport’s first collection of fiction, it is the work of a fully mature artist. -

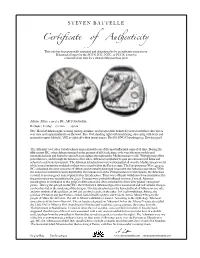

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

The Shield of Heracles (Hes

chapter 4 The Shield of Heracles (Hes. Sc. 139–320) 4.1 Introduction The next extant ekphrasis in ancient Greek Literature is found in the pseudo- Hesiodic Shield. The Shield is a small-scale epic poem of 480 hexameters, named after its central section which deals with Heracles’ shield. The poem is usually dated to the first third of the sixth century BC. It narrates an episode from the life of Heracles: the killing of Cycnus, a son of Ares. Heracles is por- trayed throughout the poem in a positive light: Zeus has fathered Heracles as a protector against ruin for gods and for men (ὥς ῥα θεοῖσιν / ἀνδράσι τ’ ἀλφηστῇσιν ἀρῆς ἀλκτῆρα φυτεύσαι, 28–29).1 By killing Cycnus, who robs travellers on their way to Delphi, Heracles lives up to this purpose. The poem is generally regarded as a product of an oral tradition.2 The fact that the Shield is oral poetry has consequences for its understanding. Thus, the idea that the Shield is a mere imitation of Achilles’ shield in Il. 18.478–608— a verdict that goes back to Aristophanes of Byzantium—must be rejected.3 It is doubtful whether in the sixth century BC fixed texts of the Iliad existed, to which another text, that of the Shield, could refer.4 This is very much a Hellenis- tic point of view. Rather, it is more plausible that both texts came into being in a still-fluid oral tradition, which contained certain stock formulae and themes.5 One common element in the tradition might well have been a shield ekphrasis, which could serve as a showpiece of the poet.6 The poet of the Shield has indeed composed his shield ekphrasis as a show- piece: Heracles’ shield is noisier, more sensational, more gruesome, but above all bigger than Achilles’ shield. -

"Works Cited." Experiencing Hektor: Character in the . London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017

Kozak, Lynn. "Works Cited." Experiencing Hektor: Character in the . London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 281–298. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 5 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474245470.0009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 5 October 2021, 20:46 UTC. Copyright © Lynn Kozak 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. W o r k s C i t e d Abad-Santos , A. ( 2016 ), ‘ Negan has fi nally arrived on Th e Walking Dead. Here’s why he’s so important. ’ vox.com , 3 April . Available online: http://www.vox.com/2016/4/3/ 11353504/walking- dead-negan Adams , E. ( 2015 ) ‘ Game of Th rones (newbies) : “ Hardhome” ’, A.V. Club , 31 May . Available online: http://www.avclub.com/tvclub/game- thrones-newbies- hardhome-220153 Ahl , F. ( 1989 ), ‘ Homer, Vergil, and complex narrative structures in Latin epic: an essay ’, Illinois Classical Studies, 14 ( 1/2 ): 1–31 . Alden , M. ( 2000 ), Homer Beside Himself: Para-Narratives in the I l i a d , O x f o r d : O x f o r d University Press . Alexiou , M. ( 1974 ), Th e Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition , O x f o r d : O x f o r d U n i v e r s i t y Press . Allen , R. C. ( 2004 ), ‘ Making Sense of Soaps ’, in Th e Television Studies Reader , e d s R . C . H i l l a n d A n n e t t e H i l l , R o u t l e d g e . -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

The Shields of Achilles and Aeneas: the Worlds Portrayed by Homer and Vergil

Vanessa Peters The Shields of Achilles and Aeneas: The Worlds Portrayed by Homer and Vergil The epic simile is a common device in epic poetry; it forms a relationship between two un- likely things and causes one to be viewed through the lens of the other. Unlike a normal simile, an epic simile has a fully developed vehicle that reflects the complexity back on the tenor; that is, an epic sim- ile, in its increased length and depth, can have layers of complexity that a normal simile cannot. The shield of Achilles (Hom. Il. 18.558-709) in Book 18 of Homer’s Iliad and the shield of Aeneas (Verg. Aen. 8.738-858) in book 8 of Vergil’s Aeneid are examples of epic similes, in which the poet takes the role of the god who forges the shield and can comment on society unobtrusively.1 These shields convey different perspectives of Greek and Roman society. Whereas Homer shows the world of peace in con- trast to the world of war to illustrate the tragedy of the Iliad, Vergil expresses Roman triumphalism to glorify Rome and her people. Book 18 of the Iliad marks a turning point in the epic. In it, Achilles decides to return to bat- tle in order to avenge Patroclus’ death by killing Hector. Since he has lost his armour to the enemy, his mother Thetis, knowing that his fate is sealed, beseeches Hephaestus to forge him a new set (Il. 18.534). The god agrees to her request and sets out to work, creating a magnificent shield for Achilles to wear in battle. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica

ARCTOS Acta Philologica Fennica VOL. LI HELSINKI 2017 INDEX Heikki Solin Rolf Westman in Memoriam 9 Ria Berg Toiletries and Taverns. Cosmetic Sets in Small 13 Houses, Hospitia and Lupanaria at Pompeii Maurizio Colombo Il prezzo dell'oro dal 300 al 325/330 41 e ILS 9420 = SupplIt V, 253–255 nr. 3 Lee Fratantuono Pallasne Exurere Classem: Minerva in the Aeneid 63 Janne Ikäheimo Buried Under? Re-examining the Topography 89 Jari-Matti Kuusela & and Geology of the Allia Battlefield Eero Jarva Boris Kayachev Ciris 204: an Emendation 111 Olli Salomies An Inscription from Pheradi Maius in Africa 115 (AE 1927, 28 = ILTun. 25) Umberto Soldovieri Una nuova dedica a Iuppiter da Pompei e l'origine 135 di L. Ninnius Quadratus, tribunus plebis 58 a.C. Divna Soleil Héraclès le premier mélancolique : 147 Origines d'une figure exemplaire Heikki Solin Analecta epigraphica 319–321 167 Holger Thesleff Pivotal Play and Irony in Platonic Dialogues 179 De novis libris iudicia 220 Index librorum in hoc volumine recensorum 277 Libri nobis missi 283 Index scriptorum 286 Arctos 51 (2017) 63–88 PALLASNE EXURERE CLASSEM: MINERVA IN THE AENEID Lee Fratantuono The goddess Minerva is a key figure in the theology of Virgil's Aeneid, though there has been relatively little written to explicate all of the scenes in the epic in which she plays a part or receives a reference.1 The present study seeks to provide a commentary on every mention of Pallas Athena/Minerva in Virgil's poetic corpus, with the intention of illustrating how the goddess plays a crucial role in the unfolding drama of the transition from a Trojan to an Italian identity for the future Rome, and in particular how the Volscian heroine Camilla serves as a mortal incarnation of the Minerva who was a patroness of battles and the military arts. -

Homer's Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon

Homer’s Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon Epic and Mythology The Homeric Epics are probably the oldest Greek literary texts that we have,1 and their subject is select episodes from the Trojan War. The Iliad deals with a short period in the tenth year of the war;2 the Odyssey is set in the period covered by Odysseus’ return from the war to his homeland of Ithaca, beginning with his departure from Calypso’s island after a 7-year stay. The Trojan War was actually the material for a large body of legend that formed a major part of Greek myth (see Introduction). But the narrative itself cannot be taken as a mythographic one, unlike the narrative of Hesiod (see ch. 1.3) - its purpose is not to narrate myth. Epic and myth may be closely linked, but they are not identical (see Introduction), and the distance between the two poses a particular difficulty for us as we try to negotiate the the mythological material that the narrative on the one hand tells and on the other hand only alludes to. Allusion will become a key term as we progress. The Trojan War, as a whole then, was the material dealt with in the collection of epics known as the ‘Epic Cycle’, but which the Iliad and Odyssey allude to. The Epic Cycle however does not survive except for a few fragments and short summaries by a late author, but it was an important source for classical tragedy, and for later epics that aimed to fill in the gaps left by Homer, whether in Greek - the Posthomerica of Quintus of Smyrna (maybe 3 c AD), and the Capture of Troy of Tryphiodoros (3 c AD) - or in Latin - Virgil’s Aeneid (1 c BC), or Ovid’s ‘Iliad’ in the Metamorphoses (1 c AD).