Coulton Mill Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

Land Stillington Road Brandsby, York, Yo61

LAND STILLINGTON ROAD BRANDSBY, YORK, YO61 4RT 1.80 ACRES (0.73 HA) of GRASSLAND WITH GOOD ACCESS & ROAD FRONTAGE This sale presents an excellent opportunity to purchase a well sheltered paddock situated near Brandsby, approximately eleven miles north of York. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY AS A WHOLE York Auction Centre, Murton, York YO19 5GF Tel: 01904 489731 Fax: 01904 489782 Email: [email protected] LOCATION: SPORTING AND MINERAL RIGHTS: The land is located south of the village of Brandsby, As far as they are owned, they are included in the sale. and is approximately 11 miles north of the York outer ring road. LOCAL AUTHORITY: Hambleton District Council, Stone Cross, DIRECTIONS: Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL6 2UU. Tel: 0845 Take the B1363 heading north from York and 1211555. continue until you reach Stillington. Continue north on the B1363 out of Stillington, through Marton Abbey PLANS, AREAS AND SCHEDULES: and towards Brandsby for approximately 2.8 miles. The plans provided and areas stated in these sales The land on is located on the right and is indicated by particulars are for guidance only and are subject to our Stephenson and Son ‘For Sale’ board. verification with the title deeds. THE LAND: VIEWING: The land comprises 1.80 acres (0.73 hectares) or Strictly by appointment only with the Selling Agents thereabouts of agricultural land and is currently down 01904 489731 / [email protected]. to grass. The land falls within the Dunkeswisk series as Interested parties are asked to contact Bill Smith on slowly permeable seasonally waterlogged fine loamy 07894 697759/ 01904 489731 or email: and fine loamy over clayey soils associated with similar [email protected]. -

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter August 2014

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter August 2014 Welcome to the Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter Well. Is this a perfect summer? After all the rain, it's so good to see that the farmers, the crops, all our plants and little animals are benefitting from the warmth. Lets hope the sun stays out for the August car boot sale, the tennis matches and the market - all of which feature in this issue. And how fine that the Worsley’s are celebrating 450 years of living in Hovingham, and the school is about to sound the trumpet for their 150th anniversary. Enjoy this sunny issue. Margaret Bell Contributions for the June issue are welcome. Please send them to [email protected] by 15th Sept 2013 Newsletter NOW available in COLOUR for friends and family, anywhere around the world D o w n l o ad f r o m o u r w eb si t e w w w . h o vi n gh am . o rg. u k o r su bsc r i b e by e m ai l t o n ew sl et t er @ h o v i n gh am . o r g. u k Hovingham features in world premiere at Ryedale Festival The Ryedale Festival opening concert featured Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s (b.1980) world premier of her ‘Ryedale Concerto’. She says she was “particularly inspired by the Howardian Hills, Castle Howard and the wonderful North Yorkshire Moors railway”; and the three movements track those domains. “The first movement describes a walk around Hovingham, along the Ebor Way, seeing Ampleforth Abbey in the distance, visiting Stonegrave village and the Minster there. -

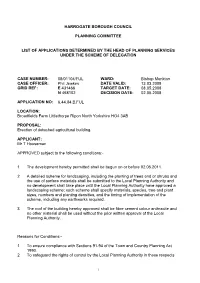

Harrogate Borough Council Planning Committee List of Applications Determined by the Head of Planning Services Under the Scheme O

HARROGATE BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE LIST OF APPLICATIONS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF PLANNING SERVICES UNDER THE SCHEME OF DELEGATION CASE NUMBER: 08/01104/FUL WARD: Bishop Monkton CASE OFFICER: Phil Jewkes DATE VALID: 13.03.2008 GRID REF: E 431466 TARGET DATE: 08.05.2008 N 468102 DECISION DATE: 02.05.2008 APPLICATION NO: 6.44.84.B.FUL LOCATION: Broadfields Farm Littlethorpe Ripon North Yorkshire HG4 3AB PROPOSAL: Erection of detached agricultural building. APPLICANT: Mr T Houseman APPROVED subject to the following conditions:- 1 The development hereby permitted shall be begun on or before 02.05.2011. 2 A detailed scheme for landscaping, including the planting of trees and or shrubs and the use of surface materials shall be submitted to the Local Planning Authority and no development shall take place until the Local Planning Authority have approved a landscaping scheme; such scheme shall specify materials, species, tree and plant sizes, numbers and planting densities, and the timing of implementation of the scheme, including any earthworks required. 3 The roof of the building hereby approved shall be fibre cement colour anthracite and no other material shall be used without the prior written approval of the Local Planning Authority. Reasons for Conditions:- 1 To ensure compliance with Sections 91-94 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. 2 To safeguard the rights of control by the Local Planning Authority in these respects 1 and in the interests of amenity. 3 In the interests of visual amenity. JUSTIFICATION FOR GRANTING CONSENT The proposed farm building would relate to and complement the existing farm buildings and would not have any significant detrimental impact on the open countryside. -

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter December 2019

The Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter December 2019 Welcome to the Hovingham and Scackleton Newsletter It’s nearly Christmas ……. and there is plenty to do over the next few weeks, featured below. Whether you still need to do Christmas shopping at one of our fabulous December markets, or are in need of some uplifting Christmas spirit from one of the Carol singing events! This year, we are also fortunate to have the tree recycling on offer again in January. There are plenty of regular articles and updates in this edition of the Newsletter. You won’t be surprised to learn that October has been an exceedingly wet month. So, enjoy reading. Wishing you all a happy, healthy Christmas & New Year. Nicole Robson Keep those stories coming to newsletter @hovingham.org.uk - Next edition copy deadline is 20th January 2020 Contact: [email protected] or (01653)-628364 Published and © 2019 by The Hovingham & Scackleton Newsletter Group. Views are not necessarily those of Group or Parish Council Hovingham Chapel Christmas Services 2 On Sunday 15th December we will hold our Carol Service at 10.30am in Hovingham Methodist Chapel with the service led by Rev Brian Shackleton. We look forward to welcoming anyone who wishes to join us. On Sunday 22nd December there will be an Ecumenical Village Carol Service at 6.30pm at The Worsley Arms Hotel with Rev Ken Gowland and Rev Martin Allwood. All welcome. Sue Goodwill th Carol Concert - 7 December CONCERT FOR ADVENT & CHRISTMAS - WITH CAROLS and AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION AMPLEFORTH and RYEDALE CONCERT CHOIR th pm S a t u r d a y 7 D e c e m b e r 5 All Saints’ Church, Hovingham TICKETS £10 each (Includes mulled wine and mince pies, children under 16 years free) Tickets available at Hovingham Village Shop, (01653) 628386 or 628922, or at the door In aid of All Saints’ Church Repair Fund Recycle your ‘real’ Christmas Trees for a ‘greener’ Christmas Please bring your real Christmas Trees (up to 6” (15cm) diameter trunk), to the seating area in the Village Hall Car Park, after 7th and before 13th January 2020. -

Yearsley Moor Archaeological Project 2009–2013 Over 4000 Years of History

Yearsley Moor Archaeological Project 2009–2013 Over 4000 years of history 1 Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. 3 List of Tables .................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 5 1. Preamble .................................................................................................................... 6 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 7 The wider climatic context ........................................................................................... 7 The wider human context ............................................................................................ 7 Previously recorded Historic Monuments for Yearsley Moor ....................................... 9 3. Individual Projects ..................................................................................................... 10 3a. Report of the results of the documentary research.............................................. 11 3b The barrows survey .............................................................................................. 28 3c Gilling deer park: the park pale survey ................................................................. 31 3d The Yearsley–Gilling -

Change & Reform Brandsby

To whom belongs the land: Change and Reform on a North Riding Estate 1889 to 1914. Hugh Charles Fairfax-Cholmeley inherited the Brandsby and Stearsby estate in 1889, at the age of 25. The Cholmeleys had held Brandsby since the mid 1500s and from 1885 the remnants of the Fairfax estate in Gilling and Coulton were added. This estate was in the North Riding of Yorkshire: Hugh was squire for 51 years from April 1889 to April 1940. This is the story of the reform programme he implemented from 1889 up to 1914, in a climate of diminishing agricultural returns. During his time the estate was transformed, socially and structurally, and a quiet revolution in farming practices began, which has continued in the following years. He continued to work in the service of agricultural reform in Brandsby and district up to his death in 1940 at the age of 76 through times of increasing hardship. At the end of the nineteenth century, the ‘Land Question’ was much discussed: the distribution of land ownership and social and political privileges were being questioned and were expressed in Liberal policies.1 Squire Hugh believed that it was his job to manage the land under his control in the interests of all those who depended on it and ultimately for the benefit of the nation. As will be shown below, Hugh looked for open discussion as to what government policy on land management should be, but pending any change, he held firmly to his beliefs. From early in his tenure, Hugh recognised that the days of the gentry living in style off the land were over. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

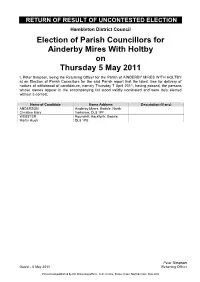

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale -

Of Land at Yearsley, Easingwold, York

104.40 ACRES (42.25 HECTARES) OF LAND AT YEARSLEY, EASINGWOLD, YORK A valuable block of commercial arable land capable of cereals, root cropping or grassland situated between the villages of Brandsby and Yearsley, approximately 5 miles from Easingwold and 16 miles from York. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY PRICE GUIDE : £950,000 - £1,000,000 General Information Services: The property is connected to mains water with one trough metered from Yearsley village, and a second trough metered from the road to the East, opposite Intake Lodge. Situation: The land lies just to the East of Yearsley and less than one mile N orth West of Brandsby. Schedule: The postcode for Yearsley is YO61 4SL. SCHEDULE OF AREAS : The Council road between the villages of Brandsby and Yearsley adjoins the Eastern boundary, and Brandsby is on the B1363 from York to Helmsley. Field Gross Area Eligible Area Claimed Acerage Description: Number (Ha) (Ha) Area (Ha) A single field in a ring fence divided into two parcel numbers for Basic Payment purposes. Field 8404 is gently sloping South facing arable land which is free draining. Classified as SE5874 -8404 102.77 41.59 41.59 41.55 grade 3 it is predominantly in the Rivington 1 Soil Series being a well drained course loam SE5873 -5592 1.63 0.66 0.65 0.65 soil over sandstone. 104.40 ac 104.38 ac 42.20 ha TOTAL AREA Parcel number 5592 is a small area of permanent grassland. (42.25 ha) (42.24 ha) Basic Payment Scheme: Sporting and Mineral Rights: The land is registered for the purposes of the Basic Payment Scheme and the sale includes The Sporting and Mineral Rights are in hand and included in the sale. -

FEARBY Conservation Area Character Appraisal

FEARBY Conservation Area Character Appraisal Approved 26 January 2011 Fearby Conservation Area Character Appraisal - Approved January 2011 p. 33 Contents Page 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Planning policy framework ............................................................................................ 2 3 Historic development & archaeology............................................................................. 3 4 Location & landscape setting ........................................................................................ 5 5. Landscape character .................................................................................................... 6 6. The form & character of buildings ................................................................................11 7. Character area analysis ............................................................................................. 16 Map 1: Historic development ........................................................................................... 21 Map 2: Conservation Area boundary .............................................................................. 22 Map 3: Analysis & concepts ............................................................................................. 23 Map 4: Landscape analysis ............................................................................................ -

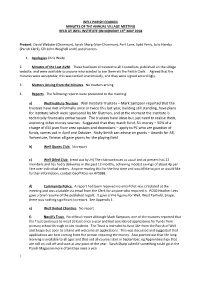

Mark Sampson Reported That the Trustees Have Met

WELL PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL VILLAGE MEETING HELD AT WELL INSTITUTE ON MONDAY 14th MAY 2018 Present: David Webster (Chairman), Sarah Sharp (Vice-Chairman), Avril Lane, Sydd Perry, Julia Hamby (Parish Clerk), Cllr John Weighell and 6 parishioners. 1. Apologies Chris Wade 2. Minutes of the Last AVM. These had been circulated to all Councillors, published on the village website, and were available to anyone who wanted to see them via the Parish Clerk. Agreed that the minutes were acceptable; this was carried unanimously, and they were signed accordingly. 3. Matters Arising from the Minutes. No matters arising 4. Reports. The following reports were presented to the meeting: a) Well Institute Trustees. Well Institute Trustees – Mark Sampson reported that the trustees have met informally once or twice this last year, building still standing, have plans for Institute which were sponsored by Mr Glatman, and at the moment the Institute is technically financially embarrassed. The trustees have ideas but just need to realise them, exploring other money sources. Suggested that they match fund, SIL money – 50% of a charge of £55 psm floor area upstairs and downstairs – apply to PC who are guardian of funds, comes out in April and October. Nicky Smith can advise on grants – Awards for All, Yorventure, Tarmac all gave grants for the playing field b) Well Quoits Club. No report c) Well Oiled Club. (read out by JH) The club continues as usual and at present has 22 members and has had 5 deliveries in the past 12 months, achieving modest savings of about 4p per litre over individual orders.