Change & Reform Brandsby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Stillington Road Brandsby, York, Yo61

LAND STILLINGTON ROAD BRANDSBY, YORK, YO61 4RT 1.80 ACRES (0.73 HA) of GRASSLAND WITH GOOD ACCESS & ROAD FRONTAGE This sale presents an excellent opportunity to purchase a well sheltered paddock situated near Brandsby, approximately eleven miles north of York. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY AS A WHOLE York Auction Centre, Murton, York YO19 5GF Tel: 01904 489731 Fax: 01904 489782 Email: [email protected] LOCATION: SPORTING AND MINERAL RIGHTS: The land is located south of the village of Brandsby, As far as they are owned, they are included in the sale. and is approximately 11 miles north of the York outer ring road. LOCAL AUTHORITY: Hambleton District Council, Stone Cross, DIRECTIONS: Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL6 2UU. Tel: 0845 Take the B1363 heading north from York and 1211555. continue until you reach Stillington. Continue north on the B1363 out of Stillington, through Marton Abbey PLANS, AREAS AND SCHEDULES: and towards Brandsby for approximately 2.8 miles. The plans provided and areas stated in these sales The land on is located on the right and is indicated by particulars are for guidance only and are subject to our Stephenson and Son ‘For Sale’ board. verification with the title deeds. THE LAND: VIEWING: The land comprises 1.80 acres (0.73 hectares) or Strictly by appointment only with the Selling Agents thereabouts of agricultural land and is currently down 01904 489731 / [email protected]. to grass. The land falls within the Dunkeswisk series as Interested parties are asked to contact Bill Smith on slowly permeable seasonally waterlogged fine loamy 07894 697759/ 01904 489731 or email: and fine loamy over clayey soils associated with similar [email protected]. -

Yearsley Moor Archaeological Project 2009–2013 Over 4000 Years of History

Yearsley Moor Archaeological Project 2009–2013 Over 4000 years of history 1 Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. 3 List of Tables .................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 5 1. Preamble .................................................................................................................... 6 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 7 The wider climatic context ........................................................................................... 7 The wider human context ............................................................................................ 7 Previously recorded Historic Monuments for Yearsley Moor ....................................... 9 3. Individual Projects ..................................................................................................... 10 3a. Report of the results of the documentary research.............................................. 11 3b The barrows survey .............................................................................................. 28 3c Gilling deer park: the park pale survey ................................................................. 31 3d The Yearsley–Gilling -

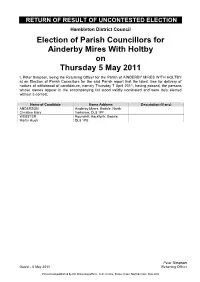

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale -

Of Land at Yearsley, Easingwold, York

104.40 ACRES (42.25 HECTARES) OF LAND AT YEARSLEY, EASINGWOLD, YORK A valuable block of commercial arable land capable of cereals, root cropping or grassland situated between the villages of Brandsby and Yearsley, approximately 5 miles from Easingwold and 16 miles from York. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY PRICE GUIDE : £950,000 - £1,000,000 General Information Services: The property is connected to mains water with one trough metered from Yearsley village, and a second trough metered from the road to the East, opposite Intake Lodge. Situation: The land lies just to the East of Yearsley and less than one mile N orth West of Brandsby. Schedule: The postcode for Yearsley is YO61 4SL. SCHEDULE OF AREAS : The Council road between the villages of Brandsby and Yearsley adjoins the Eastern boundary, and Brandsby is on the B1363 from York to Helmsley. Field Gross Area Eligible Area Claimed Acerage Description: Number (Ha) (Ha) Area (Ha) A single field in a ring fence divided into two parcel numbers for Basic Payment purposes. Field 8404 is gently sloping South facing arable land which is free draining. Classified as SE5874 -8404 102.77 41.59 41.59 41.55 grade 3 it is predominantly in the Rivington 1 Soil Series being a well drained course loam SE5873 -5592 1.63 0.66 0.65 0.65 soil over sandstone. 104.40 ac 104.38 ac 42.20 ha TOTAL AREA Parcel number 5592 is a small area of permanent grassland. (42.25 ha) (42.24 ha) Basic Payment Scheme: Sporting and Mineral Rights: The land is registered for the purposes of the Basic Payment Scheme and the sale includes The Sporting and Mineral Rights are in hand and included in the sale. -

Howardian Hills AONB Annex , Item

HOWARDIAN HILLS AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY TEXT-ONLY VERSION MANAGEMENT PLAN 2014 – 2019 the need to manage ecosystems in an integrated fashion, linking goals on wildlife, water, soil and landscape, and working at a scale that respects natural systems. This management plan also makes the important connection between people and nature. I am pleased to hear that local communities have been central to the development of the plan, and will be at the heart of its delivery. From volunteers on nature conservation projects, to businesses working to promote sustainable tourism, it’s great to hear of the enthusiasm and commitment of the local people who hold their AONBs so dear. Ministerial Foreword AONBs are, and will continue to be, landscapes of change. Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) are some of our finest Management plans such as this are vital in ensuring these changes landscapes. They are cherished by residents and visitors alike and are for the better. I would like to thank all those who were involved in allow millions of people from all walks of life to understand and bringing this plan together and I wish you every success in bringing it connect with nature. to fruition. I am pleased to see that this management plan demonstrates how AONB Partnerships can continue to protect these precious environments despite the significant challenges they face. With a changing climate, the increasing demands of a growing population and in difficult economic times, I believe AONBs represent just the sort of community driven, collaborative approach needed to ensure our natural environment is maintained for generations to come. -

The Stone House, Brandsby, York YO61 4RJ

The Stone House, Brandsby, York YO61 4RJ Estate Agents Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers The Stone House, 1 Rectory Corner, Brandsby YO61 4RJ A 3 bedroomed semi -detached village property with glorious far reaching rural views 2 Formal Reception Rooms Gated Driveway & Single Garage Farmhouse Style Dining Kitchen Larger Than Average Lawned Front Garden 3 Bedrooms, Bathroom & Washroom Delightful Rural Location & Glorious Views LPG Radiator CH & Double Glazing No Onward Chain Easingwold 5 .0 miles York –Clifton Moor 12 miles Guide Price : £325 ,000 Helmsley 9.5 miles Thirsk 14 miles An impressive 3 bedroomed semi -detached stone built period property believed to have been built in 1919 enjoying an enviable elevated position on the fringes of the village affording glorious far reaching rural views across the surrounding countryside. A hallway leads off to a formal dining room with feature fireplace and a 20’6” long sitting room with open fire and rural views. The dining kitchen provides an opportunity to update, replace and restyle to taste and currently features a range of base and wall units complemented by freestanding appliance space, walk-in storage cupboard and access out to the rear garden . The 1 st floor landing leads off to 3 good sized bedrooms (smallest of which being 9’0” x 8’5”) and a house bathroom complemented by a separate washroom/wc. Other internal features of note include LPG fired radiator central heating, double glazing to all bar 1 window, stunning open views from the 2 largest bedrooms and painted period doors throughout. Externally there is a gated driveway that provides parking and access to a larger than average detach ed garage (18’0”x12’6”) , fuel store and a small paved patio garden. -

The Hayloft, Brandsby Street, Crayke, Yo61 4Tb £1,275 Per Calendar Month the Hayloft, Brandsby Street, Crayke, Yo61 4Tb

THE HAYLOFT, BRANDSBY STREET, CRAYKE, YO61 4TB £1,275 PER CALENDAR MONTH THE HAYLOFT, BRANDSBY STREET, CRAYKE, YO61 4TB Mileages: York - 14 miles, Easingwold - 3 miles (Distances Approximate) Enjoying a delightful position within this highly popular and historic village, with delightful gardens, far reaching farmland views and within walking distance of the village school and local public house The Hayloft is an attractive double fronted 3 bedroomed period cottage, recently refurbished and providing spacious and well appointed accommodation with BRAND NEW fittings and worthy of an internal inspection to fully appreciate With UPVC double glazing and oil fired central heating Staircase Reception Hall, Cloakroom/WC, Sitting room, Kitchen with Dining area, Utility room First Floor Landing, Master Bedroom, En Suite Shower room, 2 further Bedrooms, Family Bathroom/WC Large garage, car port, enclosed gardens An out-built oak framed PORCH shields a EN SUITE SHOWER ROOM with walk-in shower composite entrance door opening to a cubicle, wash hand basin and WC. STAIRCASE RECEPTION HALL with wood grain flooring and useful understairs store cupboard. BEDROOM 2 (10'2 x 9'). CLOAKROOM with pedestal wash hand basin BEDROOM 3 (14'4 x 13'7). A through room with and tiled splashback and low suite WC. fine views towards farmland, window to the front elevation and exposed ceiling beam. The SITTING ROOM is a through room, with windows to the front overlooking the period FAMILY BATHROOM with white suite comprising houses fronting Brandsby Street and windows to shaped and panelled bath with shower over and the rear overlooking the generous gardens shower screen, low suite WC and vanity basin. -

The Story of the Abbey Land

Ampleforth Journal 46:1 (1941) 1 & 89; also 47:1 (1942) 21 & 170; and 48:2 (1943) 65 THE STORY OF THE ABBEY LAND Abbot Bede Turner [Maps to accompany this paper are not yet ready] B E F O R E 1 8 0 2 ROM THE ELEVENTH CENTURY TO 1887 the township of Ampleforth had three divisions: Ampleforth St Peter’s; Ampleforth Oswaldkirk; and Ampleforth Birdforth. FThe Ordnance maps published before 1887 show the portions which belong to each division. The claims of each division are made clear by the large grants of the Ampleforth Common, to the Vicar of Ampleforth, the Rector of Oswaldkirk, and to the Rev Croft for Birdforth. The Abbey Title Deeds and the Enclosure Award are the chief sources referred to in this story. The Award is written on ‘23 skins’ with the map of the Common attached. It was signed at Northallerton on the 27th day of January, 1810 by Edward Cleaver, Esq, of Nunnington, and William Dawson, Esq, of Tadcaster, the two gentlemen appointed by the Crown to carry out the enclosure. It was also signed by Thomas Hornsby of Wombleton, Land Surveyor, and by William Lockwood of Easingwold, Attorney. Large portions of the Common were allotted to the Rev Antony Germayne, Vicar of Ampleforth in part for tithes of old enclosure: to the Rev John Pigott, Rector of Oswaldkirk in part for tithes of old enclosure: to the Rev Robert Croft as Lessee for the tithes of old enclosure: to the Prebendal Lord’s rights in St Peter’s: to John Smith, Esq of Ampleforth and to George Sootheran of Ampleforth Outhouses, as Lords of the Manor of Ampleforth in the Oswaldkirk parish. -

The Brandsby Mission

Ampleforth Journal 44:2 (1939) 114-130 THE BRANDSBY MISSION Y I 1HE following is an attempt to trace such records as exist of the priests who served Brandsby from penal times up A to April 1934, when the last Mass was said in the house of Mr W. RadclifFe. It has been impossible to form anything like a complete history because throughout no official record has been kept. Accordingly, it has only been possible to put to gether such scattered evidence as exists of priests who have served the mission there. It may be well to mention at the outset where this evidence is to be found. From 1820 up to 1923 a baptismal register was kept at Brandsby. This gives the names of priests who have served the mission on occasion, but it does not follow that they were the regular chaplains at the time when they signed the register. In some cases we know that they were not. The Catholic population being so small there are sometimes gaps of several years in which there are no entries, and it is impossible to say who may have been serving the mission. For the years covered by the registers I have only been able to give some account of the priests whose signatures occur. For the period before the register began, the evidence is still more scanty and consists of scattered references among documents published by the Catholic Records Society and elsewhere. I believe I have mentioned all those which deal with the mission at Brandsby, but they form no complete record. -

Village Link August 2020 Print

Message from Revd Liz Hassall When was the last time you had to book for a church service? They build churches pretty big so usually capacity isn’t a problem, even for our busiest services at Christmas. We are all learning now that, despite the size of the buildings, once you allow for 2m social distancing space is very limited. I am really pleased, however, that some church services are beginning again so those who don’t have internet access can join us. You will find details in the centre pages. Please note that we really do need you to book a place and you can do that by contacting the relevant churchwarden. If you can’t get to a service, do continue to join us online at http:// bylandchurches.net. Each Sunday there is a service or other resources there. During the summer holidays we are giving our video-editor a break so there may be some weeks without a local videoed service. Please contact me if you would like to help with video and sound editing in the autumn. Training provided! The challenges of getting out of lockdown have brought home to me more deeply the possible consequences of my actions. When spending time with people, it is so important to consider their safety, to mask up, to distance, to be aware that others may be more vulnerable. This is a very practical outworking of the Christian commandment to love your neighbour as yourself. As things continue to change, I hope we can recover many of the celebrations and gatherings that mark the changing seasons. -

Stillington Village History Group

Stillington The Life of a North Yorkshire Village Produced by the members of the Stillington Village History Group Editor - Dr Alan Kirkwood Project Co-ordinator - Christine Cookman Contents Acknowledgements 2 1 Introduction Alan Kirkwood 3 2 The Early History Alan Kirkwood 4 3 Round and about the Parish Helen Vester 6 4 A Working Village Gillian Sanderson 9 5 Stillington People Pete Morgan 12 6 The Big House Christine Cookman 15 7 Church and Chapel Christine Cookman 17 8 Images of Stillington The Village History Group 18 9 Stillington Country Geoff Bruce 21 10 Farming Life Elizabeth Logan 24 11 'You don't see banties ...' Christine Cookman 27 12 Stillington at War Peter Milburn 28 13 Learning and Playing Christine Cookman 32 14 Village Life The Village History Group 36 15 Into the Third Millennium Alan Kirkwood 40 First Printed May 2000 This Edition Produced November 2006 1 Acknowledgements The Group would like to acknowledge the generous assistance given by the staff of the Durham Light Infantry Museum, Easingwold Library, Green Howards Museum, Northallerton County Archive, West Yorkshire Museum and York Reference Library. They would also like to thank the holders of the following sources - School Log Books for the National School, the Wesleyan School and the Council School, School Registers, Annual Report of Inspectors 1899, Minutes of Council School 1907-1982, School Correspondence, Correspondence and Minute Books for Village Hall and Playing Fields, Parish Magazines (C & F Hutchinson) The printing of this book would not have been possible without help from the North Yorkshire County Council Millennium Fund, the Awards For All Lottery Grant for Local Groups and the Stillington Millennium Fund. -

Minutes of Brandsby-Cum-Stearsby Parish Council Meeting Held in the Cholmeley Hall on Monday 6 March at 7.30Pm

MINUTES OF BRANDSBY-CUM-STEARSBY PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE CHOLMELEY HALL ON MONDAY 6 MARCH AT 7.30PM Present: Mr R Machin (Chairman) Mr M Waite Mr J Ward Mr R Pearson Adams Mrs C Patmore The Clerk 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Mrs C Cookman (HDC) 2. MINUTES OF THE LAST PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 20 OCTOBER 2016 The Minutes having been circulated to the councillors prior to the meeting were approved and signed by the Chairman as a true record. 3. MATTERS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 3.1 Steps leading from the main road to the Cholmeley Hall & the gate at the entrance to Cholmeley Hall. The steps and gate have been repaired by Mr Richard Ward at no charge. 3.2 Defibrillator for the village See any other business. 3.3 Masonry bees in the Cholmeley Hall No progress to report. 3.4 Speed Concerns The Clerk has received an email from Jamie the Community Speed Watch Co-ordinator for NY police. A new scheme that is being launched across North Yorkshire, designed to support local communities and improve road safety by allowing residents to address speed concerns in their local area with the support of NY Police. Following the concerns in Brandsby CWS has determined this to be the most suitable outcome. Volunteers would be required from local residents. The Clerk was asked to get more information before considering this action. 4. PLANNING APPLICATIONS The following plans have been received from Hambleton District Council: - PROPOSAL: Removal of existing vehicular access and construction of new replacement access.