Yearsley Moor Archaeological Project 2009–2013 Over 4000 Years of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

The Old Rectory

The Old Rectory Oswaldwirk A magnificent Grade II listed country house with landscaped gardens, land and stunning views over the Howardian Hills The Old Rectory, Oswaldwirk, York, YO62 5XT Helmsley 4 miles, Thirsk 15 miles, York 19 miles, Harrogate 38 miles, Leeds 43 miles A wonderful tranquil setting, overlooking the Coxwold-Gilling Gap Features: Entrance hall Drawing room Sitting room Dining room Study with en-suite WC Breakfast kitchen Utility room Kitchen WC Cellars Master Bedroom with en-suite and dressing area 6 Further Bedrooms (2 en-suite) House Bathroom House shower room Landscaped gardens Triple garage Single garage Gym Workshop Barn Stables/Shoot Bothy with planning permission for residential accommodation: Kitchen, Open plan living and dining area, Bar, 2 WC’s In all about 29 acres The Property The Old Rectory is a stunning Grade II To the other end of the breakfast kitchen is listed Georgian house that is nestled on the a fabulous orangery which provides plenty south-facing bank of the Hambleton Hills, of space for dining and a seating area, overlooking the Coxwold-Gilling Gap. French doors open out on to a paved balcony The well-proportioned accommodation has which leads to steps down to the incredible been beautifully and sympathetically renovated terrace. Leading off from the breakfast kitchen to an exceedingly high standard to create an is the utility, also by Smallbone, this has an exceptional home which boasts elegant period exterior access to the front of the property and features and quality fixtures and fittings. -

Land Stillington Road Brandsby, York, Yo61

LAND STILLINGTON ROAD BRANDSBY, YORK, YO61 4RT 1.80 ACRES (0.73 HA) of GRASSLAND WITH GOOD ACCESS & ROAD FRONTAGE This sale presents an excellent opportunity to purchase a well sheltered paddock situated near Brandsby, approximately eleven miles north of York. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY AS A WHOLE York Auction Centre, Murton, York YO19 5GF Tel: 01904 489731 Fax: 01904 489782 Email: [email protected] LOCATION: SPORTING AND MINERAL RIGHTS: The land is located south of the village of Brandsby, As far as they are owned, they are included in the sale. and is approximately 11 miles north of the York outer ring road. LOCAL AUTHORITY: Hambleton District Council, Stone Cross, DIRECTIONS: Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL6 2UU. Tel: 0845 Take the B1363 heading north from York and 1211555. continue until you reach Stillington. Continue north on the B1363 out of Stillington, through Marton Abbey PLANS, AREAS AND SCHEDULES: and towards Brandsby for approximately 2.8 miles. The plans provided and areas stated in these sales The land on is located on the right and is indicated by particulars are for guidance only and are subject to our Stephenson and Son ‘For Sale’ board. verification with the title deeds. THE LAND: VIEWING: The land comprises 1.80 acres (0.73 hectares) or Strictly by appointment only with the Selling Agents thereabouts of agricultural land and is currently down 01904 489731 / [email protected]. to grass. The land falls within the Dunkeswisk series as Interested parties are asked to contact Bill Smith on slowly permeable seasonally waterlogged fine loamy 07894 697759/ 01904 489731 or email: and fine loamy over clayey soils associated with similar [email protected]. -

Trade Directories 1822-23 & 1833-4 North Yorkshire, Surnames

Trade Directories 1822-23 & 1833-4 North Yorkshire, surnames beginning with P-Q DATE SNAME FNAME / STATUS OCCUPATIONS ADDITIONAL ITEMS PLACE PARISH or PAROCHIAL CHAPELRY 1822-1823 Page Thomas farmer Cowton North Gilling 1822-1823 Page William victualler 'The Anchor' Bellmangate Guisborough 1822-1823 Page William wood turner & line wheel maker Bellmangate Guisborough 1833-1834 Page William victualler 'The Anchor' Bellmangate Guisborough 1833-1834 Page Nicholas butcher attending Market Richmond 1822-1823 Page William Sagon attorney & notary agent (insurance) Newbrough Street Scarborough 1822-1823 Page brewer & maltster Tanner Street Scarborough 1822-1823 Paley Edmund, Reverend AM vicar Easingwold Easingwold 1833-1834 Paley Henry tallow chandler Middleham Middleham 1822-1823 Palliser Richard farmer Kilvington South Kilvington South 1822-1823 Palliser Thomas farmer Kilvington South Kilvington South 1822-1823 Palliser William farmer Pickhill cum Roxby Pickhill 1822-1823 Palliser William lodging house Huntriss Row Scarborough 1822-1823 Palliser Charles bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Charles bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Henry grocery & sundries dealer Ingram Gate Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser James bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser James bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser John jnr engraver Finkle Street Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser John snr clock & watch maker Finkle Street Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser Michael whitesmith Kirkgate Jackson's Yard Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Robert watch & clock maker Finkle -

Old Stores, Coxwold, York, YO61 4AB Guide Price £575,000

Old Stores, Coxwold, York, YO61 4AB Guide price £575,000 www.joplings.com A detached stone built house with numerous character features providing an idyllic family home bordering fields at the rear. Originally the village store the accommodation is flexible as planning permission has been given to use the original shop area as either office space or residential use. Located in the picturesque village of Coxwold and a short drive from Ampleforth the property exudes charm and is deceptively spacious. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS WET ROOM 2.09m x 1.47m (6'10" x 4'10") EN SUITE BATHROOM 2.00m x 2.74m (6'7" x 9'0") The property is located in the middle of the village opposite the well Part shower boarded and part tiled. Mira Sport shower. Hand wash basin Window to the side. Panelled bath with telephone style taps known' Fauconberg Arms'. There is ample parking to the front on a built into vanity unit. Chrome ladder style heated towel rail. Wall mirror incorporating shower fitment and side screen. Walls part tiled with cobbled area. Access to the rear is down the side. with swipe control lighting. Under floor heating. Recessed lighting. mosaic tiles. Pedestal hand wash basin. WC. Shaver point incorporating light. Exposed timbers. Radiator. DINING HALL 4.60m x 3.49m (15'1" x 11'5") FIRST FLOOR Timber front entrance door. Leaded window to the front with secondary OUTSIDE double glazing. Three radiators. Stairs to First Floor. LANDING LOUNGE 5.51m x 4.65m (18'1" x 15'3") Radiator. Window to the rear. -

Change & Reform Brandsby

To whom belongs the land: Change and Reform on a North Riding Estate 1889 to 1914. Hugh Charles Fairfax-Cholmeley inherited the Brandsby and Stearsby estate in 1889, at the age of 25. The Cholmeleys had held Brandsby since the mid 1500s and from 1885 the remnants of the Fairfax estate in Gilling and Coulton were added. This estate was in the North Riding of Yorkshire: Hugh was squire for 51 years from April 1889 to April 1940. This is the story of the reform programme he implemented from 1889 up to 1914, in a climate of diminishing agricultural returns. During his time the estate was transformed, socially and structurally, and a quiet revolution in farming practices began, which has continued in the following years. He continued to work in the service of agricultural reform in Brandsby and district up to his death in 1940 at the age of 76 through times of increasing hardship. At the end of the nineteenth century, the ‘Land Question’ was much discussed: the distribution of land ownership and social and political privileges were being questioned and were expressed in Liberal policies.1 Squire Hugh believed that it was his job to manage the land under his control in the interests of all those who depended on it and ultimately for the benefit of the nation. As will be shown below, Hugh looked for open discussion as to what government policy on land management should be, but pending any change, he held firmly to his beliefs. From early in his tenure, Hugh recognised that the days of the gentry living in style off the land were over. -

Agenda for the Monthly Meeting of Potto Parish Council to Be Held on Monday, 21 January 2008 at 7.15 Pm in the Village Hall

AGENDA FOR THE MONTHLY MEETING OF POTTO PARISH COUNCIL TO BE HELD ON MONDAY, 21 JANUARY 2008 AT 7.15 PM IN THE VILLAGE HALL Meeting open to the public 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meetings held on 19 November and 17 December 2007 3. Police Report and Neighbourhood Watch. Crime statistics from NY Police 4. Planning Decisions of Hambleton District Council a. Alterations and extensions to 3 Cooper Close to form ancillary accommodation, as amended by plan received by HDC on 3 December for Mr & Mrs Harper. Approved, subject to conditions. 07/03399/FUL 5. Planning Applications a. Two storey extension to Potto Grange for Mr & Mrs Rogers 07/03646/FUL plus Application for Listed Building Consent for two storey extension 07/03648/LBC b. Alterations and extensions to Longlands, Gold Gate Lane for Mr K M Fox. 07/03775/FUL 6. Matters arising from last month’s meeting a. Footpaths b. Parish Plan c. Trees d. No Cold Calling zone e. Parish Government Conference, Scarborough 7-9 March f. CE Electric leaflets and posters g. Planning meeting with Mr Cann, Head of Development 7. Reports from County and District Councillors 8. Finance 9. Village Hall 10. Correspondence a. Hambleton District Council – Hambleton LDF draft Affordable Housing Supplementary Planning document. b. North York Moors National Park Authority – LDF Core Strategy and Development Policies document – Submission Version c. YLCA – e mail Launch of Consultation on Historic Pubs d. YLCA – e mail Power to Appoint in the new Local Government Act 2007 e. Ms A Madden – e mail YRCC Village Halls f. -

Hambleton Local Plan Local Plan Publication Draft July 2019

Hambleton Local Plan Local Plan Publication Draft July 2019 Hambleton...a place to grow Foreword iv 1 Introduction and Background 5 The Role of the Local Plan 5 Part 1: Spatial Strategy and Development Policies 9 2 Issues shaping the Local Plan 10 Spatial Portrait of Hambleton 10 Key Issues 20 3 Vision and Spatial Development Strategy 32 Spatial Vision 32 Spatial Development Strategy 35 S 1: Sustainable Development Principles 35 S 2: Strategic Priorities and Requirements 37 S 3: Spatial Distribution 41 S 4: Neighbourhood Planning 47 S 5: Development in the Countryside 49 S 6: York Green Belt 54 S 7: The Historic Environment 55 The Key Diagram 58 4 Supporting Economic Growth 61 Meeting Hambleton's Employment Requirements 61 EG 1: Meeting Hambleton's Employment Requirement 62 EG 2: Protection and Enhancement of Employment Land 65 EG 3: Town Centre Retail and Leisure Provision 71 EG 4: Management of Town Centres 75 EG 5: Vibrant Market Towns 79 EG 6: Commercial Buildings, Signs and Advertisements 83 EG 7: Rural Businesses 85 EG 8: The Visitor Economy 89 5 Supporting Housing Growth 91 Meeting Hambleton's Housing Need 91 HG 1: Housing Delivery 93 HG 2: Delivering the Right Type of Homes 96 HG 3: Affordable Housing Requirements 100 HG 4: Housing Exception Schemes 103 HG 5: Windfall Housing Development 107 HG 6: Gypsies, Travellers and Travelling Showpeople 109 Hambleton Local Plan: Publication Draft - Hambleton District Council 1 6 Supporting a High Quality Environment 111 E 1: Design 111 E 2: Amenity 118 E 3: The Natural Environment 121 E -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

Quakers in Thirsk Monthly Meeting 1650-75," Quaker Studies: Vol

Quaker Studies Volume 9 | Issue 2 Article 6 2005 Quakers in Thirsk onM thly Meeting 1650-75 John Woods [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Woods, John (2005) "Quakers in Thirsk Monthly Meeting 1650-75," Quaker Studies: Vol. 9: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES 912 (2005) [220-233] WOODS QUAKERS INTHIRSK MONTHLY MEETING 1650-75 221 ISSN 1363-013X part of the mainly factual records of sufferings, subject to the errors and mistakes that occur in recording. Further work of compilation, analysis, comparison and contrast with other areas is needed to supplement this narra tive and to interpret the material in a wider context. This interim cameo can serve as a contribution to the larger picture. QUAKERS IN THIRSK MONTHLY MEETING 1650-75 The present study investigates the area around Thirsk in Yorkshire and finds evidence that gives a slightly different emphasis from that of Davies. Membership of the local community is apparent, but, because the evidence comes from the account of the sufferings of Friends following their persecution John Woods for holding meetings for worship in their own homes, when forbidden to meet in towns, it shows that the sustained attempt in this area during the decade to prevent worship outside the Established Church did not prevent the Malton,North Yorkshire,England 1660-70 holding of Quaker Meetings for worship in the area. -

Delegated List , Item 42. PDF 44 KB

RYEDALE DISTRICT COUNCIL APPLICATIONS DETERMINED BY THE DEVELOPMENT CONTROL MANAGER IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE SCHEME OF DELEGATED DECISIONS 10th February 2020 1. Application No: 19/01111/LBC Decision: Approval Parish: Normanby Parish Meeting Applicant: Mrs Julie Gill Location: Bridge House Farm Main Street Normanby Kirkbymoorside North Yorkshire YO62 6RH Proposal: Conversion, extensions and alterations of barns and outbuildings to form wedding venue to include the creation of guest accommodation, ceremony room and reception room _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Application No: 19/01126/FUL Decision: Approval Parish: Allerston Parish Council Applicant: Mr Mark Benson Location: The Old Station Main Street Allerston Pickering North Yorkshire YO18 7PG Proposal: Change of use, conversion and alterations to eastern part of station building to form 1no. two bedroom self catering holiday let with associated parking _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Application No: 19/01129/FUL Decision: Approval Parish: Habton Parish Council Applicant: Mr & Mrs N Speakman Location: Manor Farm Ryton Rigg Road Ryton Malton North Yorkshire YO17 6RY Proposal: Change of use, conversion and alterations to agricultural building to form 2no. three bedroom dwellings including the demolition of modern agricultural buildings with associated parking _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 4. -

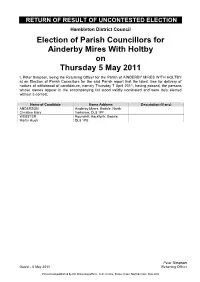

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale