Quakers in Thirsk Monthly Meeting 1650-75," Quaker Studies: Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA Introduction

The Hambleton and Howardian Hills CAN DO (Cultural and Natural Development Opportunity) Partnership The CAN DO Partnership is based around a common vision and shared aims to develop: An area of landscape, cultural heritage and biodiversity excellence benefiting the economic and social well-being of the communities who live within it. The organisations and agencies which make up the partnership have defined a geographical area which covers the south-west corner of the North York Moors National Park and the northern part of the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The individual organisations recognise that by working together resources can be used more effectively, achieving greater value overall. The agencies involved in the CAN DO Partnership are – the North York Moors National Park Authority, the Howardian Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, English Heritage, Natural England, Forestry Commission, Environment Agency, Framework for Change, Government Office for Yorkshire and the Humber, Ryedale District Council and Hambleton District Council. The area was selected because of its natural and cultural heritage diversity which includes the highest concentration of ancient woodland in the region, a nationally important concentration of veteran trees, a range of other semi-natural habitats including some of the most biologically rich sites on Jurassic Limestone in the county, designed landscapes, nationally important ecclesiastical sites and a significant concentration of archaeological remains from the Neolithic to modern times. However, the area has experienced the loss of many landscape character features over the last fifty years including the conversion of land from moorland to arable and the extensive planting of conifers on ancient woodland sites. -

The Stables Crayke Lodge

The Stables Crayke Lodge The Stables Crayke Lodge Contact Details: Daytime Phone: 0*1+244 305162839405 E*a+singw0o1l2d3 Y*O+61 4T0H1 England £ 236.00 - £ 1,040.00 per week This splendid, first floor barn conversion is set in a lovely tranquil location, just two miles from the pretty market town of Easingwold and can sleep two people in one bedroom. Facilities: Room Details: Communications: Sleeps: 2 Broadband Internet 1 Double Room Entertainment: TV 1 Bathroom Heat: Open Fire Kitchen: Cooker, Dishwasher, Fridge Outside Area: Enclosed Garden Price Included: Linen, Towels Special: Cots Available © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 3 October 2021 The Stables Crayke Lodge Recommended Attractions 1. Goodwood Art Gallery, Historic Buildings and Monuments, Nature Reserve, Parks Gardens and Woodlands, Tours and Trips, Visitor Centres and Museums, Childrens Attractions, Zoos Farms and Wildlife Parks, Bistros and Brasseries, Cafes Coffee Shops and Tearooms, Horse Riding and Pony Trekking, Shooting and Fishing, Walking and Climbing Motor circuit, Stately Home, Racecourse, Aerodrome, Forestry, Chichester, PO18 0PX, West Sussex, Organic Farm Shop, Festival of Speed, Goodwood Revival England 2. Goodwood Races Festivals and Events, Horse Racing Under the family of the Duke of Richmond, Goodwood Races sits Chichester, PO18 0PS, West Sussex, only five miles north of the town of Chichester. England 3. Arundel Castle and Gardens Historic Buildings and Monuments, Parks Gardens and Woodlands This converted Castle and Stately Home is over 1000 years old, and Arundel, BN18 9AB, West Sussex, sits on the bank of the River Arun in West Sussex England 4. Chichester Cathedral Historic Buildings and Monuments, Tours and Trips This 900 Year Old Cathedral has been visited millions of times by Chichester, PO19 1PX, West Sussex, people of all faiths and denominations. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire Wenham, Leslie P. How to cite: Wenham, Leslie P. (1946) A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HISTORY OP RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIREc i. To all those scholars, teachers, henefactors and governors who, by their loyalty, patiemce, generosity and care, have fostered the learning, promoted the welfare and built up the traditions of R. S. Y. this work is dedicated. iio A HISTORY OF RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIRE Leslie Po Wenham, M.A., MoLitt„ (late Scholar of University College, Durham) Ill, SCHOOL PRAYER. We give Thee most hiomble and hearty thanks, 0 most merciful Father, for our Founders, Governors and Benefactors, by whose benefit this school is brought up to Godliness and good learning: humbly beseeching Thee that we may answer the good intent of our Founders, "become profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth, and at last be partakers of the Glories of the Resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Implementation

CHAPTER 15 - IMPLEMENTATION CHAPTER 15 IMPLEMENTATION 15.1 The policies and proposals contained in the Local Plan must be realistic and capable of being implemented within the plan period to 2006. The effectiveness of implementation depends on the buoyancy of the local economy; the resources available to those bodies active in Harrogate District and their commitment to achievement of the Local Plan’s objectives. 15.2 This chapter considers the bodies involved in the implementation of the Local Plan and the resources they have available for putting the plan into action. It goes on to put forward specific policies to assist in the work. THE PRIVATE SECTOR 15.3 Private individuals - This group includes owner occupiers, small traders and private landlords and landowners. Taken individually, decisions made by this group tend to be small in scale. However, when considered collectively, decisions made by private individuals can markedly influence the overall economy and environment of the plan area. 15.4 Private firms - This group ranges from large industrialists and developers who can significantly affect the appearance and function of an area with a single scheme to smaller firms whose combined activities are likely to have the greatest effect on the District’s social, economic and environmental well-being. THE PUBLIC SECTOR 15.5 Harrogate Borough Council - As the local planning authority, the Council has wide ranging powers to regulate development. Most of the policies in this Local Plan will be implemented through the Council’s use of these development control powers. The Council is also a significant landowner and investor due to the many services it provides. -

Land at the Old Quarry Monk Fryston Offers Invited

Land at The Old Quarry Monk Fryston Offers Invited Land/Potential Development Site – Public Notice – We act on behalf of the Parish Council / vendors in the sale of this approximately 2/3 acre site within the development area of Monk Fryston. Any interested parties are invited to submit best and final offers (conditional or unconditional) in writing (in a sealed envelope marked ‘Quarry Land, Monk Fryston’ & your name) to the selling agents before the 1st June 2014. Stephensons Estate Agents, 43 Gowthorpe, Selby, YO8 4HE, telephone 01757 706707. • Potential Development Site • Subject to Planning Permission • Approximately 2/3 Acre • Sought After Village Selby 01757 706707 www.stephensons4property.co.uk Estate Agents Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Land at The Old Quarry, Monk Fryston Potential development site (subject to planning permission). The site extends to approximately 2/3 acre and forms part of a former quarry, located in this much sought after village of Monk Fryston. With shared access off the Main Street/Leeds Road. The successful developer/purchaser may wish to consider the possibility of a further access off Lumby Lane/Abbeystone Way, which may be available via a third party (contact details can be provided by the selling agent). The site is conveniently located for easy vehicular access to the A1/M62 motorway network and commuting to many nearby regional centres such as York, Leeds, Doncaster and Hull etc. TO VIEW LOCAL AUTHORITY By appointment with the agents Selby office. Selby District Council Civic Centre LOCATION Portholme Road Located on the edge of this much sought after village of Monk Selby Fryston and being conveniently located for access to the A1/M62 YO8 4SB motorway network and commuting to many regional centres like Telephone 01757 705101 Leeds, Wakefield, Doncaster, Tadcaster, York and Selby etc. -

Being a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

The tJni'ers1ty of Sheffield Depaz'tient of Uistory YORKSRIRB POLITICS, 1658 - 1688 being a ThesIs submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by CIthJUL IARGARRT KKI August, 1990 For my parents N One of my greater refreshments is to reflect our friendship. "* * Sir Henry Goodricke to Sir Sohn Reresby, n.d., Kxbr. 1/99. COff TENTS Ackn owl edgements I Summary ii Abbreviations iii p Introduction 1 Chapter One : Richard Cromwell, Breakdown and the 21 Restoration of Monarchy: September 1658 - May 1660 Chapter Two : Towards Settlement: 1660 - 1667 63 Chapter Three Loyalty and Opposition: 1668 - 1678 119 Chapter Four : Crisis and Re-adjustment: 1679 - 1685 191 Chapter Five : James II and Breakdown: 1685 - 1688 301 Conclusion 382 Appendix: Yorkshire )fembers of the Coir,ons 393 1679-1681 lotes 396 Bibliography 469 -i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this thesis was supported by a grant from the Department of Education and Science. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield, particularly the History Department, for the use of their facilities during my time as a post-graduate student there. Professor Anthony Fletcher has been constantly encouraging and supportive, as well as a great friend, since I began the research under his supervision. I am indebted to him for continuing to supervise my work even after he left Sheffield to take a Chair at Durham University. Following Anthony's departure from Sheffield, Professor Patrick Collinson and Dr Mark Greengrass kindly became my surrogate supervisors. Members of Sheffield History Department's Early Modern Seminar Group were a source of encouragement in the early days of my research. -

The Old Rectory

The Old Rectory Oswaldwirk A magnificent Grade II listed country house with landscaped gardens, land and stunning views over the Howardian Hills The Old Rectory, Oswaldwirk, York, YO62 5XT Helmsley 4 miles, Thirsk 15 miles, York 19 miles, Harrogate 38 miles, Leeds 43 miles A wonderful tranquil setting, overlooking the Coxwold-Gilling Gap Features: Entrance hall Drawing room Sitting room Dining room Study with en-suite WC Breakfast kitchen Utility room Kitchen WC Cellars Master Bedroom with en-suite and dressing area 6 Further Bedrooms (2 en-suite) House Bathroom House shower room Landscaped gardens Triple garage Single garage Gym Workshop Barn Stables/Shoot Bothy with planning permission for residential accommodation: Kitchen, Open plan living and dining area, Bar, 2 WC’s In all about 29 acres The Property The Old Rectory is a stunning Grade II To the other end of the breakfast kitchen is listed Georgian house that is nestled on the a fabulous orangery which provides plenty south-facing bank of the Hambleton Hills, of space for dining and a seating area, overlooking the Coxwold-Gilling Gap. French doors open out on to a paved balcony The well-proportioned accommodation has which leads to steps down to the incredible been beautifully and sympathetically renovated terrace. Leading off from the breakfast kitchen to an exceedingly high standard to create an is the utility, also by Smallbone, this has an exceptional home which boasts elegant period exterior access to the front of the property and features and quality fixtures and fittings. -

Old Stores, Coxwold, York, YO61 4AB Guide Price £575,000

Old Stores, Coxwold, York, YO61 4AB Guide price £575,000 www.joplings.com A detached stone built house with numerous character features providing an idyllic family home bordering fields at the rear. Originally the village store the accommodation is flexible as planning permission has been given to use the original shop area as either office space or residential use. Located in the picturesque village of Coxwold and a short drive from Ampleforth the property exudes charm and is deceptively spacious. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS WET ROOM 2.09m x 1.47m (6'10" x 4'10") EN SUITE BATHROOM 2.00m x 2.74m (6'7" x 9'0") The property is located in the middle of the village opposite the well Part shower boarded and part tiled. Mira Sport shower. Hand wash basin Window to the side. Panelled bath with telephone style taps known' Fauconberg Arms'. There is ample parking to the front on a built into vanity unit. Chrome ladder style heated towel rail. Wall mirror incorporating shower fitment and side screen. Walls part tiled with cobbled area. Access to the rear is down the side. with swipe control lighting. Under floor heating. Recessed lighting. mosaic tiles. Pedestal hand wash basin. WC. Shaver point incorporating light. Exposed timbers. Radiator. DINING HALL 4.60m x 3.49m (15'1" x 11'5") FIRST FLOOR Timber front entrance door. Leaded window to the front with secondary OUTSIDE double glazing. Three radiators. Stairs to First Floor. LANDING LOUNGE 5.51m x 4.65m (18'1" x 15'3") Radiator. Window to the rear. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M. Tyler Index More Information Index 1381 Rising. See Peasants’ Revolt Alcuin, 123, 159, 171 Alexander Minorita of Bremen, 66 Abbo of Fleury, 169 Alexander the Great (Alexander III), 123–4, Abbreviatio chronicarum (Matthew Paris), 230, 233 319, 324 Alfred of Beverley, Annales, 72, 73, 78 Abbreviationes chronicarum (Ralph de Alfred the Great, 105, 114, 151, 155, 159–60, 162–3, Diceto), 325 167, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176–7, 183, 190, 244, Abelard. See Peter Abelard 256, 307 Abingdon Apocalypse, 58 Allan, Alison, 98–9 Adam of Usk, 465, 467 Allen, Michael I., 56 Adam the Cellarer, 49 Alnwick, William, 205 Adomnán, Life of Columba, 301–2, 422 ‘Altitonantis’, 407–9 Ælfflæd, abbess of Whitby, 305 Ambrosius Aurelianus, 28, 33 Ælfric of Eynsham, 48, 152, 171, 180, 306, 423, Amis and Amiloun, 398 425, 426 Amphibalus, Saint, 325, 330 De oratione Moysi, 161 Amra Choluim Chille (Eulogy of St Lives of the Saints, 423 Columba), 287 Aelred of Rievaulx, 42–3, 47 An Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh (Dudly De genealogia regum Anglorum, 325 Ferbisie or McCryushy), 291 Mirror of Charity, 42–3 anachronism, 418–19 Spiritual Friendship, 43 ancestral romances, 390, 391, 398 Aeneid (Virgil), 122 Andreas, 425 Æthelbald, 175, 178, 413 Andrew of Wyntoun, 230, 232, 237 Æthelred, 160, 163, 173, 182, 307, 311 Angevin England, 94, 390, 391, 392, 393 Æthelstan, 114, 148–9, 152, 162 Angles, 32, 103–4, 146, 304–5, 308, 315–16 Æthelthryth (Etheldrede), -

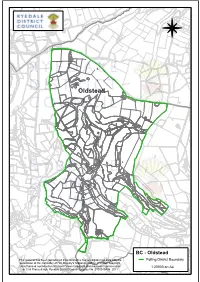

Oldstead Moor

High House Track 176.8m Quarry Hambleton High House Scawton Park (disused) Flassen Dale Cattle Grid Def Path (um) Track Byre Cottage The Pheasantry Path (um) Sinks 296.9m Stinging Gill The Rectory Stone 182.9m Reservoir (covered) Track Path (um) Track Track Path (um) Cold Kirby Moor 186.5m Hydraulic Ram (disused) Quarry (disused) Quarry (disused) 118.4m Scawton 291.7m Spreads Hill Top Farm Collects Track Flassen Dale 201.2m Hill Top Vicarage Farm Issues Track Cottages Quarry N Hydraulic Ram (disused) (disused) Def Brignal Gill Church Farm Issues Track St Mary's Church Track Path (um) 283.2m TCB Issues (DISUSED) BACK LANE Cleave Dike 207.6m Stables Old Rectory Track Doll Spring Pond Farm Sinks Farm Issues Issues Track Fircroft Track Rose Cottage W Stone Garth E Pond Quarry Track C Tk (disused) Track Hambleton House Leveret House Cliff Garbutt Farm Track Hare Inn (PH) Track Cleave Dike (course of) 273.4m Path (um) Cote Moor Track Flassen Gill Slack Path (um) The Granary Gill Bank 218.8m Flassen Gill S Cliff 242.3m Pond Scawton Moor House C Tk Track Hotel Plantation Posts Track Car Park Cliff Plantation 262.7m Pumping Station Def Hambleton Plantation Casten Dike Track CD Scawton Moor Plantation Def Waterfall Gill Slack Cleave Dike Lay-by Reservoir (covered) Car Path (um) Park CD Hambleton FW CP & ED Bdy Path (um) Hambleton Def Lodge Post 274.0m Def Posts ED & Ward Bdy National Park FW The FW Car Information Centre Hambleton Park 248.1m Stables Inn Path (um) Def Stone FW Post 232.3m Def 273.1m Picnic Area 269.3m FW A 170 Casten Cottage A -

Bailey & Battalion Court

BAILEY & BATTALION COURT HIGH QUALITY OFFICE BUILDINGS A1(M) J53/54 COLBURN BUSINESS PARK CATTERICK FOR SALE / TO LET NORTH YORKSHIRE DL9 4QL FLEXIBLE WORKSPACE FROM: 1,215 SQ FT (113 SQ M) TO 4,500 SQ FT (418 SQ M) www.colburnbusinesspark.co.uk Colburn Business Park LAST REMAINING UNITS TO A1(M) TERICK RD BAILEY COURT T BATTALION COURT A A6136 C TARGET TO RICHMOND NEWCASTLE 40 MILES INNOVATE 60 A167 A689 A6072 A178 A177 RIVER TEES NEWCASTLE 40 MILES A688 59 60 A167 A689 COLBURN BUSINESS PARK Bailey and Battalion Court provide a range of new high quality A6072 A178 suites and office buildings from 1215 sq ft to 4500 sq ft (113 sq m BARTON A177 A688 59 RIVER TEES A68 Bailey & Battalion Court are situated within Colburn Business to 418 sq m). Buildings are capable of being subdivided or STOCKTON-ON-TEES Park which is accessed off the A6136 Catterick Road and is combined and have been designed to meet56 the needs of the A68 56 58 A167 STOCKTON-ON-TEES MIDDLESBROUGH situated next to Catterick Garrison. The development is situated modern occupier. 58 A167 MIDDLESBROUGH A67 A66 A67 A66 approximately 1.5 miles from the A1(M), which has been A1(M) DARLINGTON All the buildings are arranged in Gladman’s acclaimedLORRY courtyard A67 A174 A1(M) DARLINGTON A174 recently subject to significant upgrading and in turn links DARLINGTON A66(M) STATION A67 design, set within a secure environment, providing PARKa practical B6275 DURHAM TEES DARLINGTON with both the regional and national transport networks. -

Land East of Cookson Way Brough with Saint Giles, Catterick North Yorkshire, DL9 4XG

Land East of Cookson Way Brough with Saint Giles, Catterick North Yorkshire, DL9 4XG Residential Development Opportunity Approximately 4.23 hectares (10.47 acres) with Outline Planning Permission for up to 107 new houses. www.thomlinsons.co uk Land East of Cookson Way, Brough With St Giles, Catterick, North Yorkshire, DL9 4XG Situation and Description Local Planning Authority The Village of Brough with St Giles is situated in the Richmondshire District Council desirable Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire Station Road within two miles of Catterick Garrison and five miles Richmond from the Yorkshire Dales market town of Richmond. North Yorkshire DL10 4JX It is an ideal base for commuting around the region, being within 2 miles from the A1(M) which gives direct [email protected] access to York (42 miles), Teesside (30 miles), Newcastle Tel 01748 829100 (47 miles), and Leeds (52 miles) with further motorway connections of the M62/M1 accessible in under an Planning Application Information hour. Northallerton railway station is within 14 miles, The site has been promoted by White Acre Estates giving connections, north to Darlington, Newcastle and Limited on behalf of the landowners. As part of Scotland and south to York and beyond. Both Leeds/ the application process, a comprehensive list of Bradford, Durham Tees Valley and Newcastle airports technical documents have been submitted to support are also within 50 miles. the application and ensure that the development Catterick offers a small number of shops, a pharmacy, is technically deliverable. The documents are public houses and take aways as well as the well known available to download from the website of the Sole race course.