Sterne Und Weltraum 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

July 2020 in This Issue Online Readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 Click on Images an Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for Hyperlinks

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Recent back issues: http://moon.scopesandscapes.com/tlo_back.html July 2020 In This Issue Online readers, ALPO Conference November 6-7, 2020 2 Lunar Calendar July 2020 3 click on images An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 for hyperlinks. Observations Received 4 By the Numbers 7 Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 4 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 9 Call For Observations Focus-On 9 Focus-On Announcement 10 2020 ALPO The Walter H. Haas Observer’s Award 11 Sirsalis T, R. Hays, Jr. 12 Long Crack, R. Hill 13 Musings on Theophilus, H. Eskildsen 14 Almost Full, R. Hill 16 Northern Moon, H. Eskildsen 17 Northwest Moon and Horrebow, H. Eskildsen 18 A Bit of Thebit, R. Hill 19 Euclides D in the Landscape of the Mare Cognitum (and Two Kipukas?), A. Anunziato 20 On the South Shore, R. Hill 22 Focus On: The Lunar 100, Features 11-20, J. Hubbell 23 Recent Topographic Studies 43 Lunar Geologic Change Detection Program T. Cook 120 Key to Images in this Issue 134 These are the modern Golden Days of lunar studies in a way, with so many new resources available to lu- nar observers. Recently, we have mentioned Robert Garfinkle’s opus Luna Cognita and the new lunar map by the USGS. This month brings us the updated, 7th edition of the Virtual Moon Atlas. These are all wonderful resources for your lunar studies. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

GRAIL Gravity Observations of the Transition from Complex Crater to Peak-Ring Basin on the Moon: Implications for Crustal Structure and Impact Basin Formation

Icarus 292 (2017) 54–73 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus GRAIL gravity observations of the transition from complex crater to peak-ring basin on the Moon: Implications for crustal structure and impact basin formation ∗ David M.H. Baker a,b, , James W. Head a, Roger J. Phillips c, Gregory A. Neumann b, Carver J. Bierson d, David E. Smith e, Maria T. Zuber e a Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912, USA b NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA c Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA d Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA e Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: High-resolution gravity data from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission provide Received 14 September 2016 the opportunity to analyze the detailed gravity and crustal structure of impact features in the morpho- Revised 1 March 2017 logical transition from complex craters to peak-ring basins on the Moon. We calculate average radial Accepted 21 March 2017 profiles of free-air anomalies and Bouguer anomalies for peak-ring basins, protobasins, and the largest Available online 22 March 2017 complex craters. Complex craters and protobasins have free-air anomalies that are positively correlated with surface topography, unlike the prominent lunar mascons (positive free-air anomalies in areas of low elevation) associated with large basins. -

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center South Carolina Department of Natural Resources http://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/sertc/ Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center Invertebrate Literature Library (updated 9 May 2012, 4056 entries) (1958-1959). Proceedings of the salt marsh conference held at the Marine Institute of the University of Georgia, Apollo Island, Georgia March 25-28, 1958. Salt Marsh Conference, The Marine Institute, University of Georgia, Sapelo Island, Georgia, Marine Institute of the University of Georgia. (1975). Phylum Arthropoda: Crustacea, Amphipoda: Caprellidea. Light's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. R. I. Smith and J. T. Carlton, University of California Press. (1975). Phylum Arthropoda: Crustacea, Amphipoda: Gammaridea. Light's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. R. I. Smith and J. T. Carlton, University of California Press. (1981). Stomatopods. FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Eastern Central Atlantic; fishing areas 34,47 (in part).Canada Funds-in Trust. Ottawa, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, by arrangement with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, vols. 1-7. W. Fischer, G. Bianchi and W. B. Scott. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Volume II. Final report to the Minerals Management Service. J. M. Uebelacker and P. G. Johnson. Mobile, AL, Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Volume III. Final report to the Minerals Management Service. J. M. Uebelacker and P. G. Johnson. Mobile, AL, Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. -

Science Concept 3: Key Planetary

Science Concept 6: The Moon is an Accessible Laboratory for Studying the Impact Process on Planetary Scales Science Concept 6: The Moon is an accessible laboratory for studying the impact process on planetary scales Science Goals: a. Characterize the existence and extent of melt sheet differentiation. b. Determine the structure of multi-ring impact basins. c. Quantify the effects of planetary characteristics (composition, density, impact velocities) on crater formation and morphology. d. Measure the extent of lateral and vertical mixing of local and ejecta material. INTRODUCTION Impact cratering is a fundamental geological process which is ubiquitous throughout the Solar System. Impacts have been linked with the formation of bodies (e.g. the Moon; Hartmann and Davis, 1975), terrestrial mass extinctions (e.g. the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary extinction; Alvarez et al., 1980), and even proposed as a transfer mechanism for life between planetary bodies (Chyba et al., 1994). However, the importance of impacts and impact cratering has only been realized within the last 50 or so years. Here we briefly introduce the topic of impact cratering. The main crater types and their features are outlined as well as their formation mechanisms. Scaling laws, which attempt to link impacts at a variety of scales, are also introduced. Finally, we note the lack of extraterrestrial crater samples and how Science Concept 6 addresses this. Crater Types There are three distinct crater types: simple craters, complex craters, and multi-ring basins (Fig. 6.1). The type of crater produced in an impact is dependent upon the size, density, and speed of the impactor, as well as the strength and gravitational field of the target. -

On Lucian's Hyperanthropos and Nietzsche's Übermensch

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections Spring 2013 Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Parodic Style: On Lucian’s Hyperanthropos and Nietzsche’s Übermensch Babette Babich Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Continental Philosophy Commons, German Literature Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, "Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Parodic Style: On Lucian’s Hyperanthropos and Nietzsche’s Übermensch" (2013). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 56. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article DIOGENES Diogenes 58(4) 58 –74 Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Parodic Copyright © ICPHS 2012 Reprints and permissions: Style: On Lucian’s Hyperanthropos sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0392192112467410 and Nietzsche’s Übermensch dio.sagepub.com Babette Babich Fordham University, New York City Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s Empedocles I here undertake to read Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke -

Observing the Lunar Libration Zones

Observing the Lunar Libration Zones Alexander Vandenbohede 2005 Many Look, Few Observe (Harold Hill, 1991) Table of Contents Introduction 1 1 Libration and libration zones 3 2 Mare Orientale 14 3 South Pole 18 4 Mare Australe 23 5 Mare Marginis and Mare Smithii 26 6 Mare Humboldtianum 29 7 North Pole 33 8 Oceanus Procellarum 37 Appendix I: Observational Circumstances and Equipment 43 Appendix II: Time Stratigraphical Table of the Moon and the Lunar Geological Map 44 Appendix III: Bibliography 46 Introduction – Why Observe the Libration Zones? You might think that, because the Moon always keeps the same hemisphere turned towards the Earth as a consequence of its captured rotation, we always see the same 50% of the lunar surface. Well, this is not true. Because of the complicated motion of the Moon (see chapter 1) we can see a little bit around the east and west limb and over the north and south poles. The result is that we can observe 59% of the lunar surface. This extra 9% of lunar soil is called the libration zones because the motion, a gentle wobbling of the Moon in the Earth’s sky responsible for this, is called libration. In spite of the remainder of the lunar Earth-faced side, observing and even the basic task of identifying formations in the libration zones is not easy. The formations are foreshortened and seen highly edge-on. Obviously, you will need to know when libration favours which part of the lunar limb and how much you can look around the Moon’s limb. -

Investigations of Water-Bearing Environments on the Moon and Mars

Investigations of Water-Bearing Environments on the Moon and Mars by Julie Mitchell A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2017 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Philip R. Christensen, Chair James F. Bell III Steven Desch Hilairy E. Hartnett Mark Robinson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 ABSTRACT Water is a critical resource for future human missions, and is necessary for understanding the evolution of the Solar System. The Moon and Mars have water in various forms and are therefore high-priority targets in the search for accessible extraterrestrial water. Complementary remote sensing analyses coupled with laboratory and field studies are necessary to provide a scientific context for future lunar and Mars exploration. In this thesis, I use multiple techniques to investigate the presence of water- ice at the lunar poles and the properties of martian chloride minerals, whose evolution is intricately linked with liquid water. Permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) at the lunar poles may contain substantial water ice, but radar signatures at PSRs could indicate water ice or large block populations. Mini-RF radar and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Narrow Angle Camera (LROC NAC) products were used to assess block abundances where radar signatures indicated potential ice deposits. While the majority of PSRs in this study indicated large block populations and a low likelihood of water ice, one crater – Rozhdestvenskiy N – showed indirect indications of water ice in its interior. Chloride deposits indicate regions where the last substantial liquid water existed on Mars. Major ion abundances and expected precipitation sequences of terrestrial chloride brines could provide context for assessing the provenance of martian chloride deposits. -

September 2020 the Lunar Observer by the Numbers

A publication of the Lunar Section of ALPO Edited by David Teske: [email protected] 2162 Enon Road, Louisville, Mississippi, USA Back issues: http://www.alpo-astronomy.org/ September 2020 In This Issue Check out 2020 ALPO Conference Announcement 2 Lunar Calendar August 2020 3 the ALPO An Invitation to Join ALPO 3 Observations Received 4 Virtual By the Numbers 6 Conference Submission Through the ALPO Image Achieve 7 When Submitting Observations to the ALPO Lunar Section 8 Page 2 Call For Observations Focus-On 8 Focus-On Announcement 9 Little Brother, R. Hill 10 Taruntius, Craters, Domes and Many Rilles, D. Teske 11 Another Dream Bridge in the Shore of Mare Crisium, A. Anunziato 12 Online readers, North of Brahe, R. Hill 15 click on images Carrel, a Copernican Crater in Mare Tranquillitatis, A. Anunziato 16 for hyperlinks The Ends, R. Hill 17 Detection and Identification of Two Rille-like Features South of Crater Linnè G. R. Lena and KC Pau 18 From Philosopher to Bay of Rainbows, R. Hill 24 The Lunar 100, A. Anunziato 25 Focus-On, Lunar Targets 21-30, J. Hubbell 26 Recent Topographic Studies 48 Pico, R. H. Hays, Jr. 60 Messier and Messier A, R. H. Hays, Jr. 64 Silberschlag and Rima Ariadaeus, R. H. Hays, Jr. 80 Ariadaeus and Sosigenes A, R. H. Hays, Jr. 81 Lunar Geographic Change Detection Program, T. Cook 110 Key to Images in this Issue 118 Warm greetings to all. This issue marks my first year of editing The Lunar Observer. It amazes me all the high quality lunar work that is sent in for publication. -

Image Map of the Moon

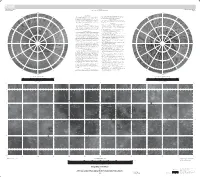

U.S. Department of the Interior Prepared for the Scientific Investigations Map 3316 U.S. Geological Survey National Aeronautics and Space Administration Sheet 1 of 2 180° 0° 5555°° –55° Rowland 150°E MAP DESCRIPTION used for printing. However, some selected well-known features less that 85 km in diameter or 30°E 210°E length were included. For a complete list of the IAU-approved nomenclature for the Moon, see the This image mosaic is based on data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Wide Angle 330°E 6060°° Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature at http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. For lunar mission C l a v i u s –60°–60˚ Camera (WAC; Robinson and others, 2010), an instrument on the National Aeronautics and names, only successful landers are shown, not impactors or expended orbiters. Space Administration (NASA) Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft (Tooley and others, 2010). The WAC is a seven band (321 nanometers [nm], 360 nm, 415 nm, 566 nm, 604 nm, 643 nm, and 689 nm) push frame imager with a 90° field of view in monochrome mode, and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS B i r k h o f f Emden 60° field of view in color mode. From the nominal 50-kilometer (km) polar orbit, the WAC This map was made possible with thanks to NASA, the LRO mission, and the Lunar Recon- Scheiner Avogadro acquires images with a 57-km swath-width and a typical length of 105 km. At nadir, the pixel naissance Orbiter Camera team. The map was funded by NASA's Planetary Geology and Geophys- scale for the visible filters (415–689 nm) is 75 meters (Speyerer and others, 2011).