“For King of Jerusalem Is Your Name”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

Annual Report 2016-17

The Schechter Institutes, Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 מכון שכטר למדעי היהדות The Schechter Institutes, Inc. is a not for profit (501-c-3) organization dedicated to the advancement of pluralistic Jewish education. The Schechter Institutes, Inc. provides support to four non-profit organizations based in Jerusalem, Israel and forms an educational umbrella that includes: ■ Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, the largest M.A. program in Jewish Studies in Israel with 500 Israeli students and more than 1600 graduates. ■ Schechter Rabbinical Seminary is the international rabbinical school of Masorti Judaism, serving Israel, Europe and the Americas. ■ TALI Education Fund offers a pluralistic Jewish studies program to 48,000 children in 325 Israeli secular public schools and kindergartens. ■ Midreshet Yerushalayim provides Jewish education to Jewish communities throughout Ukraine. ■ Midreshet Schechter offers adult Jewish education Bet Midrash frameworks throughout Israel. ■ Neve Schechter-Legacy Heritage Center for Jewish Culture in Neve Zedek draws 15,000 Tel Avivans every year to concerts, classes, cultural events and art exhibits. Written and edited by Linda Price Photo Credits: Felix Doktor, Olivier Fitoussi, Avi Hayun, Moriah Karsagi-Aharon, Jorge Novominsky, Linda Price, Matan Shitrit, Ben Yagbes, Yossi Zamir Graphic Design: Stephanie and Ruti Design Shavua Tov | A Good Week @ Schechter Table of Contents Letters from the Chair and the President 2 A Good Week @ Schechter 4 Schechter Institute Graduate School 10 Scholarship for the Community -

NATIONS UNIES Dietr

NATIONS UNIES Dietr. GENERALE ASSEMB1f.E CONSE Il A/36/m 0 E s É c u F . - A S!14400 GÉNÉRALE ORIGINAL : ANGLAIS ASSEMBLEEGENERALE CONSEIL DE SECURITE Trente-sixième session Trente-sixième année Points 31 et Gir de la liste préliminairex QUESTION DE PALESTINE RAZPORT DU COMITE SPECIAL CHARGE D'ENQUETER SUR LES PRATIQUES ISRAELIENNES AFFECTANT LES DROITS DE L'HOMME DE LA POPULATION DES TERRITOIRES OCCUPES Lettre datée du 10 mars 1981, adressée au Secrétaire &&a1 par le Représentant permanent de la Jordanie auprès de l'Organisation des Nations Unies J'ai l'honneur de vous transmettre ci-joint, comme EI. le rabbin Moshe Hirsch m'en a prié dans une lettre datée du 8 mars 1981, le message qu'il vous adresse au nom de "NeLurei Karta" de Jérusalem, au sujet du comportement sauvage et sacrilège des forces de sécurité sionistes, qui, le 7 mars 1981, ont violemment assailli sans provucation des centaines de juifs orthodoxes sans défense dans l'enceinte sacrée de leur synagogue et du Yeshiva Toldos Aharon, dans l'ancien quartier Mea Shearim-Batei Ungarin, qui jouxte plusieurs quartiers arabes et coexiste avec eux dans la fraternit6. Mor.breux sont les citryene de Jérusalem - et j'en suis - qui ont toujours éprouv6 & 1'6gard des adeptes sin&cs du judaïsme un sentiment d'affinité et l'estisx et le respect dus & des gens qui se vouent aane faillir & servir, par lcal.m3 paPslee et par leurs actes, rande religion et leur8 nobles trwditicns. C, sont depuis d*innombrables &ifrntions, le8 derniers d~~~it~ire$ de l'authentique tradition judatque. -

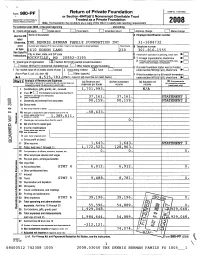

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF I

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I • or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2 00 8 For calendar year 2008 , or tax year beginning , and ending R ('hark au that annh, F__l Ind,sl return F__] 9:m2l rahirn I-1 e,nonnorl ratnrn 1 1 Adrlrocc nhanno hI,mn ,.h^nno Name of Use the IRS foundation A Employer identification number label Otherwise , HE DENNIS BERMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 31-1684732 print Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number or type . 5410 EDSON LANE 220 301-816-1555 See Specific City or town, state , and ZIP code Instructions . C If exemption application is pending , check here OCKVILLE , MD 20852-319 5 D 1- Foreign organizations , check here ► 2. Foreignrganrzatac meetingthe85%test, H Check tYPtype oorganization 0X Section 501 (c)( 3 ) exempt Pprivate foundation check heere and atttach computation Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foun dation status was termina ted I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method OX Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) = Other (specify ) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis) ► $ 4 , 515 , 783 . -

FROM VISION to REALITY Celebrating 50 Years of Excellence in Torah and Technology JCT Perspective

FROM VISION TO REALITY Celebrating 50 Years of Excellence in Torah and Technology JCT Perspective Rosh Hashanah 5780 September 2019 Vol. 23 COMMENTARY Jerusalem College JCT’s future and Jerusalem’s future: an of Technology – inextricable connection Lev Academic Center As I reflect on the significance of JCT’s 50th anniversary, I’m reminded of a different milestone President that occurred two years ago: the 50th anniversary Prof. Chaim Sukenik of a reunified Jerusalem. Rabbinic Head th Rav Yosef Zvi Rimon Just like Jerusalem’s 50 , JCT’s 50th serves not only Rector as a time to celebrate, but as an unmistakable call Prof. Kenneth Hochberg to action. It is time to create a more equitable socioeconomic reality for all Director General residents of Israel’s eternal capital. Yosef Zeira Jerusalem has long been the poorest of Israel’s major cities — largely Vice President Stuart Hershkowitz because it has the country’s highest concentration of Arabs and Haredim, communities with disproportionately high poverty rates. Editor Rosalind Elbaum As Jerusalem is the center of the Jewish world, it is incumbent upon the Copy Editor Jewish people to help ensure a brighter future for vulnerable populations J Cubed Communications in this city. That imperative is at the heart of JCT’s institutional mission. Content Editor Debbie Ross Alongside 52 years of a reunified Jerusalem, JCT’s 50 years are defined by Staff our inspiring work to endow Israel’s underserved populations with the Ronit Kullok gifts of academia and employment. Indeed, from the Haredi community Tzipporah Eisen to Ethiopian-Israelis, JCT has pioneered academic solutions to acute Photography employment conundrums. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08810-8 — Jewish Radical Ultra-Orthodoxy Confronts Modernity, Zionism and Women's Equality Motti Inbari Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08810-8 — Jewish Radical Ultra-Orthodoxy Confronts Modernity, Zionism and Women's Equality Motti Inbari Index More Information Index Adler Benzion, 37 Ba’al Shem Tov, 106, 108, 119 Adler Naftali, 10 Baal, 102, 204 Admor of Sanz, 155 Baer Yitzhak, 178 Admor of Shinava, 121, 125 Bais Ruchel, 157 Agron Gershon, 86 Balfour Declaration, 17, 21, 24, 26, 41, Agudat Yisrael, 6, 13, 16, 21–2, 27–30, 39, 102, 141 42–3, 45, 52–7, 59–60, 72–3, 77, 91, Bar Kochva Revolt, 219 95, 98, 103, 109, 111–15, 117, 131, Bar Yochai Rabbi Shimon, 106, 108, 122, 183 138, 141, 147–9, 151, 156–7, 162, Batei Ungarin, 51 182, 184, 186, 199–201 Becker Kurt, 143–4 Council of Torah Sages, 59 Beis Ruchel, 199 Ahavat Yisrael, 197 Beis Yaacov, 54, 56, 72, 113, 157 Alfandri Shlomo Eliezer, 103–11, 124–7, Beit Iksa village, 32, 36–7 183 Ben David Ruth, 18, 32, 59–61, 65, 71, 171 Aliyat neshama, 193 Yossele Schumacher Affair, 60 Alliance Israélite Universelle, 110 Ben David Uriel, 60 Alter Avraham Mordechai (“The Gerrer Ben Gurion David, 28, 60 Rebbe”), 7, 18, 27, 94, 102, 111–15, Ben Shalom Yisrael, 210, 212, 222 126 Ben Zvi Yitzhak, 28, 111 Alter Itzhak Meir (“the Rim”), 97 Benedict Yechiel, 88 Alter Yehuda Leib, 97 Bengis Zelig Reuven, 162 Altshuler Mor, 96, 105 Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, 144–5, Amital Yehuda, 224 147–8 Antiochus, 216, 221 Bernstein Moshe Leib, 26 Apostate, 40, 42, 117, 185 Black Bureau, 10 Arab option, 26, 29, 70 Blau Amram, 2, 15, 17, 28, 33, 36, 38–9, Arab Revolt, 38–9, 105 44, 70–3, 77–80, 83–4, 91–2, 188, -

Herod's Western Palace in Jerusalem: Some New Insights

ELECTRUM * Vol. 26 (2019): 53–72 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.19.003.11206 www.ejournals.eu/electrum HEROD’S WESTERN PALACE IN JERUSALEM: SOME NEW INSIGHTS Orit Peleg-Barkat The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Abstract: Despite Josephus’ detailed description of Herod’s palace built on the Southwestern Hill of Jerusalem in Bellum Judaicum, book 5, only scant archaeological remains from its substructure were revealed so far, and only few scholars have attempted reconstructing its plan and decora- tion. A group of monumental Ionic columns, alongside a sculpted head of a lion, found in the Southwestern Hill in the vicinity of the supposed location of the palace, seems to have originated from the palace complex, attesting to its grandeur and unique character. Combining this evidence with Josephus’ description and our vast knowledge of Herod’s palatial architecture, based on ex- cavated palace remains in other sites, such as Jericho, Herodium, Masada, Caesarea Maritima and Machaerus, allows us to present a clearer picture of the main palace of this great builder. Keywords: Jerusalem, Second Temple Period, King Herod, Flavius Josephus, Architectural Dec- oration, Roman Architecture, Royal Ideology. Introduction Amongst the client kings1 of the early Roman Empire, Herod, King of Judaea (37–4 BCE), is unmistakably the best known to scholarship, thanks to the detailed historical testimony of Josephus2 and the rich and well-preserved archaeological remains from his immense building program. These remains belong to a large array of sites and structures that he built within his kingdom, as well as beyond its boundaries, including entire cit- ies, palace complexes, fortifications and fortresses, temples and temeni, theatres and hippodromes, bathhouses, mausolea, harbours, paved streets, and more.3 Most dominant 1 The term “client-king” is used here for reasons of convenience. -

The Jewish Observer

AN18-MINUTE-A-OAY LEARNING PROGRAM T}Je RLeINMAN ebITION For people on the go. For people who make their minutes count. For people who want the stimulation of classic Torah sources every single day. Even if you have a regular learning seder, A Daily Dose will add more learning and excitement to your day - every day! Every volume will provide 4 weeks of provocative and enjoyable Daily Doses of Torah study. Over the course of the year, there will be 13 four-week volumes - plus a fourteenth volume on the Festivals. The Daily Dose of Torah will enrich your day - every single day of the year. For a free Preview Sample of a full week, go to your local Judaica bookstore, call our office at 1-800 MESORAH, or visit our website: ww_~~{!.ar_t~crqIJ.co.r!l.!_(f_ajly~_q~~-· The Patrons of The Umud YomVA Daily Dose of Torah initiative are Elly and Brochie Kleinman. Dedications of individual volumes are available - especially appropriate for weeks of a yahrzeit or anniversaries. Now available: Volume 1 - Bereishis, Noach, Lech Lecha, Vayeira SPECIAL INTRODUCTORY PRICE: $9.99 Convenient and portable 5Y2 - x 8% - page size / hardcover/ 208 pages. ··-----·-·.... --- ----··---------- -- .. ·-------~·- ----·--·------·-·--- IN THIS ISSUE THE JEWISH OBSERVER {ISSN) 002.1·6615 IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY, EXCIOl'T JULY & AUGUST AND A COMBINED ISSUE FOR LESSONS FROM LEBANON JANllAIW/fEBRUARY, BY THE AGIJDATH ISltAEL Of AMERICA, 42. BROADWAY, NEW YORK, NY 10004, 7 INTRODUCTION PE!llOOICA!.S POSTAGE PAil) IN NEW YORK. NY. S\JBSCR!f'TION S2.5.00/YEAR; 8 THE FOOTSTEPS OF MOSH/ACH, 2. -

Jerusalem Reborn By: Rabbi Jeremy Rosen

Jerusalem reborn by: Rabbi Jeremy Rosen The Jerusalem I first came to in 1958 was a very different and much smaller town than the Jerusalem of nearly one million it is today. There was no Old City. It was cut off by the Wall, the one built by the Jordanians on parts of the demilitarized ceasefire zone, to keep the Old City out of bounds to Jews. The Jordanians had destroyed the Jewish Quarter and expelled its population for the first time since a once more enlightened Islam got rid of the Crusaders in 1187 CE. The New Jerusalem extended westward in all directions. Despite the different areas and suburbs, it was intimate and warm. Long before Zionism, pious Jews came to live in Jerusalem and inhabited the Jewish Quarter in the Old City. In the nineteenth century as numbers increased they began to build suburbs outside the walls. Sephardi Jews came from Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent and Persia. The Ashkenazim from Eastern Europe. They built buildings that clustered around courtyards, markets and wells. Looking inward protectively, like walled cities against marauding enemies and robbers. To the North lay the Ultra-Orthodox area of Meah Shearim called “A hundred- fold,” not “A hundred gates” (Genesis 26.12). It was built in 1874 to provide more salubrious housing than the cramped Hebrew Quarters in the Old City. But also for the poor and the elderly. There within its boundaries lay Batei Polin, houses for Polish Jews, built in 1891, and Batei Ungarin 1891 for Hungarians and Batei Varsha in 1894. If initially they were a big improvement over the cramped Old city, by the time I arrived in the 1950’s they were showing their age, overcrowded and badly maintained. -

Nurse-Nurse-WEB.Pdf

01 אגף 02זיו של בית החולים ביקור חולים ב־1939, אוסף ספריית הקונגרס )American Colony (Jerusalem Ziv Wing, Bikur Cholim Hospital, 1939, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, American Colony (Jerusalem( زيف وينغ، مستشفى بيكور حوليم، 1939، مكتبة الكونغرس، واشنطن العاصمة، الكولونية األمريكية )القدس) לשושנה אדלשטיין To Shoshana Adelestein لشوشانا إدلشتاين תנועה ציבורית الحركة العامة Public MoveMent 27 מיכל היימן ميخال هايمن Michal heiMan 31 איה בן רון آية بن رون aya ben Ron 38 כרם נאטור كرم ناطور KaRaM natouR 42 רן סלפק ران سالباك Ran SlaPaK 46 יורי קופר يوري كوبر yuRi KuPeR 50 נלי אגסי نيلي اغاسي nelly agaSSi 54 רעות אסימיני رعوت اسيميني Reut aSiMini 58 גדעון גכטמן غدعون غخطمان gideon gechtMan 62 יסמין ורדי ياسمين فاردي JaSMin vaRdi 66 הדסה גולדויכט هداسا جولدفيخت hadaSSa goldvicht 70 קבוצת המבחנה مجموعة أنبوب االختبار the teStube gRouP 74 תומר ספיר تومر سبير toMeR SaPiR 78 שרון בלבן شارون بلبان ShaRon balaban 82 מורן לי יקיר موران لي يكير MoRan lee yaKiR 86 אנדי ארנוביץ أندي أرنوفيتش andi aRnovitz 90 חן כהן حين كوهين chen cohen 94 מראה הצבה InstallatIon vIew شكل العمل اإلنشائي 05 צילום: שניר קציר Photo: Snir Kazir تصوير: سنير كتسير מראה הצבה InstallatIon vIew شكل العمل اإلنشائي 06 צילום: שניר קציר Photo: Snir Kazir تصوير: سنير كتسير מראה הצבה InstallatIon vIew شكل العمل اإلنشائي 07 צילום: שניר קציר Photo: Snir Kazir تصوير: سنير كتسير חילוץ Rescue إنقاذ 08תינוקות בעריסות תנועה ואחיות מטפלות ציבוריתבבית חולים ביקור חולים, MoveMentירושלים. 1940Public-1950. באדיבות יד בן צביحركة جماهيرية Infants in cribs with nurses in Bikur Cholim Hospital, Jerusalem, 1950-1940. -

Kol Mevaseret 5780

קול Kol מבשרת Mevaseret A Compilation of Insights and Analyses of Torah Topics by the students of MICHLELET MEVASERET YERUSHALAYIM Jerusalem, 5780 Editors in Chief: Sophie Frankenthal ● Tali Gershov ● Jessica Zemble Editorial Staff: Tamar Eisenberg ● Aliza Mandelbaum Aliza Pfeffer ● Rena Rush ● Rina Soffer Devora Weintraub ● Sara Weiss ● Maya Wind Faculty Advisor: Rabbi Eliezer Lerner © 2020 / 5780 – All rights reserved Printed in Israel מכללת מבשרת ירושלים Michlelet Mevaseret Yerushalayim Rabbi David Katz, Director Mrs. Sharon Isaacson, Asst. Director Mrs. Sarah Dena Katz, Asst. Director Derech Chevron 60 Jerusalem 93513 Tel: (02) 652-7257 / US Tel: (212) 372-7226 Fax: (02) 652-7162 / US Fax: (917)-793-1047 [email protected] U.S. Mailing Address 500 W. Burr Blvd Suite #47 Teaneck, NJ 07666 www.mevaseret.org/mmy HaDaF Typesetting [email protected] CONTENTS Letter from the Editors ............................................7 Introduction Rabbi David Katz ................................................... 9 תנ"ך A Two-Way Street: A Message of Shir HaShirim Shoshana Berger.................................................. 15 Self, Service, and Servitude: Servant Leadership Throughout Tanach Sophie Frankenthal .............................................. 21 ויראת מאלקיך Tali Gershov ........................................................ 31 Eishet Potiphar and Esther HaMalka Eliana Hirsch ....................................................... 37 Haftarat Miketz – Mishpat Shlomo Riva Krishtul....................................................... -

Jerusalem, Producedannuallybythejerusaleminstituteforpolicyresearch

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research The Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research (formerly the Jerusalem Institute 2016 for Israel Studies) is the leading institute in Israel for the study of Jerusalem’s JERUSALEM complex reality and unique social fabric. Established in 1978, the Institute focuses on the unique challenges facing Jerusalem in our time and provides extensive, in-depth knowledge for policy makers, academia, and the general public. FACTS AND TRENDS The work of the Institute spans all aspects of the city: physical and urban planning, social and demographic issues, economic and environmental Maya Choshen, Michal Korach, Dafna Shemer challenges, and questions arising from the geo-political status of Jerusalem. AND TRENDS JERUSALEM FACTS Its many years of multi-disciplinary work have afforded the Institute a unique perspective that allows it to expand its research and address complex challenges confronting Israeli society in a comprehensive manner. These challenges include urban, social, and strategic issues; environmental and sustainability challenges; and innovation and financing. Jerusalem: Facts and Trends provides a concise, up-to-date picture of the current state of affairs and trends of change in the city across a wide range of issues: population, employment, education, tourism, construction, and other areas. The main source of data for the publication is The Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem, produced annually by the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. M. Choshen, M. Korach, D. Shemer M. Choshen, Korach, 461 2016 מכון ירושלים JERUSALEM למחקרי מדיניות Jerusalem Institute for Policy Reaserch INSTITUTE FOR POLICY 20 Radak st., Jerusalem 9218604 Tel +972-2-563-0175 Fax +972-2-5639814 Email [email protected] WWW.JIIS.ORG RESEARCH JERUSALEM INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2016 The State of the City and Changing Trends Maya Choshen, Michal Korach, Dafna Shemer Jerusalem, 2016 PUBLICATION NO.