Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan Assessing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The LRA in Kafia Kingi

The LRA in Kafia Kingi The suspension of the Ugandan army operation in the Central African Republic (CAR) following the overthrow of the CAR regime in March 2013 may have given some respite to the LRA, which by the first quarter of 2013 appeared to be at its weakest in its long history. As of May 2013, there were some 500 LRA members in numerous small groups scattered in CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Sudan. Of these 500, about half were combatants, including up to 200 Ugandans and 50 low-ranking fighters abducted primarily from ethnic Zande com- munities in CAR, DRC, and South Sudan. At least one LRA group, including Kony, was reportedly based near the Dafak Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) garrison in the disputed area of Kafia Kingi for over a year, until February or early March 2013.1 Reports of LRA presence in Kafia Kingi have been made since early 2010. A recent publication contained a detailed account of the history of LRA groups in the area complete with satellite imagery showing the location of a possible LRA camp at close proximity to a SAF garrison.2 In April 2013, Col. al Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ada, the official SAF spokesperson, told the Sudanese official news agency SUNA, ‘ the report [showing an alleged LRA camp in Kafia Kingi] is baseless and rejected,’ adding, ‘SAF has no interest in adopting or sheltering rebels from other countries.’3 But interviews with former LRA members who recently defected confirm that a large LRA group of over 100 people, including LRA leader Joseph Kony, spent about a year in Kafia Kingi. -

'When Will This End and What Will It Take?'

‘When will this end and what will it take?’ People’s perspectives on addressing the Lord’s Resistance Army conflict Logo using multiply on layers November 2011 Logo drawn as seperate elements with overlaps coloured seperately ‘ With all the armies of the world here, why isn’t Kony dead yet and the conflict over? When will this end and what will it take?’ Civil society leader, Democratic Republic of Congo CHAD SUDAN Birao Southern Darfur Kafia Kingi Sam-Ouandja Western Wau Zemongo Game Bahr-El-Ghazal CENTRAL Reserve AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC Haut-Mbomou Djemah Bria Western Equatoria Bambouti Ezo Obo Nzara Juba Zemio Yambio Bambari Mbomou Mboki Maridi Rafai Central Magwi Bangassou Bangui Banda Equatoria Bas-Uélé GARAMBA Yei Nimule Ango PARK Lake Doruma Kitgum Turkana Niangara Dungu Duru Arua Faradje Haut Uélé Gulu Lira Bunia Soroti LakeLake AlbertAlbert DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO UGANDA Kampala LRA area of operation after Operation Lightning Thunder LakeLake VictoriaVictoria end of 2008–11 LRA area of operation during the Juba talks 2006–08 RWANDA LRA area of operation during Operation Iron Fist 2002–05 0 150 300km BURUNDI TANZANIA © Conciliation Resources. This map is intended for illustrative purposes only. Borders, names and other features are presented according to common practice in the region. Conciliation Resources take no position on whether this representation is legally or politically valid. Disclaimer Acknowledgements This document has been produced with the Conciliation Resources is grateful to Frank financial assistance of the European Union van Acker who conducted the research and and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Uganda. contributed to the analysis in this report. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Dominic Ongwen's Domino Effect

DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT HOW THE FALLOUT FROM A FORMER CHILD SOLDIER’S DEFECTION IS UNDERMINING JOSEPH KONY’S CONTROL OVER THE LRA JANUARY 2017 DOMINIC ONGWEN’S DOMINO EFFECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Map: Dominic Ongwen’s domino effect on the LRA I. Kony’s grip begins to loosen 4 Map: LRA combatants killed, 2012–2016 II. The fallout from the Ongwen saga 7 Photo: Achaye Doctor and Kidega Alala III. Achaye’s splinter group regroups and recruits in DRC 9 Photo: Children abducted by Achaye’s splinter group IV. A fractured LRA targets eastern CAR 11 Graph: Abductions by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 Map: Attacks by LRA factions in eastern CAR, 2016 V. Encouraging defections from a fractured LRA 15 Graph: The decline of the LRA’s combatant force, 1999–2016 Conclusion 19 About The LRA Crisis Tracker & Contributors 20 LRA CRISIS TRACKER LRA CRISIS TRACKER EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since founding the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda in the late 1980s, Joseph Kony’s control over the group’s command structure has been remarkably durable. Despite having no formal military training, he has motivated and ruled LRA members with a mixture of harsh discipline, incentives, and clever manipulation. When necessary, he has demoted or executed dozens of commanders that he perceived as threats to his power. Though Kony still commands the LRA, the weakening of his grip over the group’s command structure has been exposed by a dramatic series of events involving former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen. In late 2014, a group of Ugandan LRA officers, including Ongwen, began plotting to defect from the LRA. -

Country Report Sudan at a Glance: 2003-04

Country Report June 2003 Sudan Sudan at a glance: 2003-04 OVERVIEW The peace process between the government and the leading southern rebel force, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, will be kept alive by international pressure, although little of substance will be agreed in the short term. A ceasefire remains in effect until the end of June, while talks have been suspended until July. A US presidential report to Congress on the commitment of the Sudanese government to peace avoided calling for sanctions, signalling US support for ongoing dialogue. A significant rise in oil exports and a recovery in non-oil exports in 2003 are expected to ensure strong real GDP growth of 5.9%, slowing marginally to 5.3% in 2004. The current-account deficit, however, will widen over the forecast period to US$1.74bn by end-2004 (9.6% of GDP). Key changes from last month Political outlook • With halting progress in the peace talks, the political outlook is dependent upon the continued commitment to negotiations. Many obstacles remain, not least the role of the opposition groups not included in the talks and the growing unrest in the west of the country. Economic policy outlook • The government will not veer from its commitment to IMF-led policies, although expenditure may stray beyond agreed limits. Economic policy will continue to centre on balancing the budget through subsidy cutting and raising taxes. These measures, combined with a revised oil price forecast, will result in a reduced budget deficit of SD5.5bn (US$21.1m; 0.1% of GDP) in 2003, which will then widen in 2004 to SD33bn. -

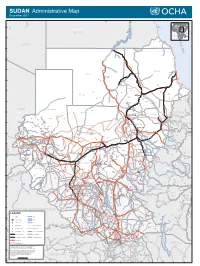

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media Relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #Defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic A

PRESS RELEASE Marina Modi Public &Media relations Officer [email protected] 0955950026 #defyhatenow: Mobilizing Civic Action against Hate Speech and Directed Social Media Incitement to Violence in South Sudan. Juba, 03 November 2017 #DEFYHATENOW WIKIPEDIA WORKSHOP #defyhatenow initiative will be training students from the University of Juba on writing and feeding /editing information about South Sudan on Wikipedia,the online global encyclopedia from 6- 9 November 2017. Objectives; 1. Empowering South Sudanese to have a global voice in national narratives and knowledge in the quest for lasting peace. 2. Generating more knowledge about other people-to-people peace-building issues. 3. Initiate a sustainable movement of South Sudanese Wikipedia writers/editors. Why Wikipedia? South Sudan is underrepresented at Wikipedia, the world's largest online encyclopedia. There are hardly 1.500 articles about South Sudanese subjects and most of them are just stubs, since even entries about many major towns and states only feature a couple of lines. While Wikipedia is one of the most used and visited websites, next to no content about South Sudan has been generated inside the country itself. Instead, most information about South Sudan has been created by outsiders. With regard to internal peace-making, #defyhatenow will be working with the student run #kefkum initiative to collaboratively edit, starting with a critical review of Wunlit conference and then create a comprehensive article on Wikipedia. As a pilot example, #defyhatenow has already edited the Wikipedia article about Deim Zubeir from a one-line stub to a multi-facetted overview. Deim Zubeir has recently been included on South Sudan's first tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage sites. -

2002-04-07 ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP On

ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON SUDAN Visit to Sudan 7th - 12th April 2002 Facilitated by Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children, Tearfund, and the British Embassy, Khartoum ASSOCIATE PARLIAMENTARY GROUP ON SUDAN Visit to Sudan 7th - 12th April 2002 Facilitated by Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children, Tearfund, and the British Embassy, Khartoum Associate Parliamentary Group on Sudan 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We visited Sudan between April 6th and 13th 2002 under the auspices of the Associate Parliamentary Group for Sudan accompanied by HM Ambassador to Sudan Richard Makepeace, Dan Silvey of Christian Aid and the Group co-ordinator Colin Robertson. Our grateful thanks go to Colin and Dan for their superb organisation, tolerance and patience, to Christian Aid, Oxfam GB, Save the Children and Tearfund for their financial and logistical support, and to Ambassador Makepeace for his unfailing courtesy, deep knowledge of the current situation and crucial introductions. Our visit to southern Sudan could not have gone ahead without the hospitality and support of Susan from Unicef in Rumbek and Julie from Tearfund at Maluakon. As well as being grateful to them and their organisations we are enormously impressed by their courage and commitment to helping people in such difficult and challenging circumstances. Thanks to the efforts of these and many others we were able to pack a huge number of meetings and discussions into a few days, across several hundred miles of the largest country in Africa. The primary purpose of our visit was to listen and learn. Everyone talked to us of peace, and of their ideas about the sort of political settlement needed to ensure that such a peace would be sustainable, with every part of the country developed for the benefit of all of its people. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 March 8, 2019

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 MARCH 8, 2019 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Insecurity in Yei results in unknown number of civilian deaths, prevents 15,000 5% 7% 20% people from receiving aid 7.1 million 7% Estimated People in South Health actors continue EVD awareness Sudan Requiring Humanitarian 10% and screening activities Assistance 19% 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan – WFP conducts first road delivery to 15% December 2018 central Unity 17% Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Health (17%) 6.5 million FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE Nutrition (15%) Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) February 2019 Shelter & Settlements (5%) USAID/FFP $398,226,647 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 1.9 million USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $624,967,8824 Estimated IDPs in BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE South Sudan SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 UN – January 31, 2019 84% 9% 5% U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,756,094,855 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE 191,238 Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases UNMISS – March 4, 2019 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Ongoing violence between Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GoRSS) and opposition forces near Central Equatoria State’s Yei area has displaced an estimated 2.3 million 7,400 people to Yei town since December and is preventing relief agencies from reaching Estimated Refugees and Asylum more than 15,000 additional people seeking safety outside of Yei, the UN reports. -

Utd^L. Dean of the Graduate School Ev .•^C>V

THE FASHODA CRISIS: A SURVEY OF ANGLO-FRENCH IMPERIAL POLICY ON THE UPPER NILE QUESTION, 1882-1899 APPROVED: Graduate ttee: Majdr Prbfessor ~y /• Minor Professor lttee Member Committee Member irman of the Department/6f History J (7-ZZyUtd^L. Dean of the Graduate School eV .•^C>v Goode, James Hubbard, The Fashoda Crisis: A Survey of Anglo-French Imperial Policy on the Upper Nile Question, 1882-1899. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December, 1971, 235 pp., bibliography, 161 titles. Early and recent interpretations of imperialism and long-range expansionist policies of Britain and France during the period of so-called "new imperialism" after 1870 are examined as factors in the causes of the Fashoda Crisis of 1898-1899. British, French, and German diplomatic docu- ments, memoirs, eye-witness accounts, journals, letters, newspaper and journal articles, and secondary works form the basis of the study. Anglo-French rivalry for overseas territories is traced from the Age of Discovery to the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, the event which, more than any other, triggered the opening up of Africa by Europeans. The British intention to build a railroad and an empire from Cairo to Capetown and the French dream of drawing a line of authority from the mouth of the Congo River to Djibouti, on the Red Sea, for Tied a huge cross of European imperialism over the African continent, The point of intersection was the mud-hut village of Fashoda on the left bank of the White Nile south of Khartoum. The. Fashoda meeting, on September 19, 1898, of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, representing France, and General Sir Herbert Kitchener, representing Britain and Egypt, touched off an international crisis, almost resulting in global war. -

Estimated Age

The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. Since 2003, we have published the calendar in a daily planner format that provides our consumers with a variety of information related to international terrorism, including wanted terrorists; terrorist group fact sheets; technical issue related to terrorist tactics, techniques, and procedures; and potential dates of importance that terrorists might consider when planning attacks. The cover of this year’s CT Calendar highlights terrorists’ growing use of social media and other emerging online technologies to recruit, radicalize, and encourage adherents to carry out attacks. This year will be the last hardcopy publication of the calendar, as growing production costs necessitate our transition to more cost- effective dissemination methods. In the coming years, NCTC will use a variety of online and other media platforms to continue to share the valuable information found in the CT Calendar with a broad customer set, including our Federal, State, Local, and Tribal law enforcement partners; agencies across the Intelligence Community; private sector partners; and the US public. On behalf of NCTC, I want to thank all the consumers of the CT Calendar during the past 12 years. We hope you continue to find the CT Calendar beneficial to your daily efforts. Sincerely, Nicholas J. Rasmussen Director The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. This edition, like others since the Calendar was first published in daily planner format in 2003, contains many features across the full range of issues pertaining to international terrorism: terrorist groups, wanted terrorists, and technical pages on various threat-related topics.