Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Liberale Opmars

ANDRÉ VERMEULEN Boom DE LIBERALE OPMARS André Vermeulen DE LIBERALE OPMARS 65 jaar v v d in de Tweede Kamer Boom Amsterdam De uitgever heeft getracht alle rechthebbenden van de illustraties te ach terhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen dat uw rechten niet zijn gehonoreerd, dan kunt u contact opnemen met Uitgeverij Boom. Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonde ringen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the writtetj permission of the publisher. © 2013 André Vermeulen Omslag: Robin Stam Binnenwerk: Zeno isbn 978 90 895 3264 o nur 680 www. uitgeverij boom .nl INHOUD Vooraf 7 Het begin: 1948-1963 9 2 Groei en bloei: 1963-1982 55 3 Trammelant en terugval: 1982-1990 139 4 De gouden jaren: 1990-2002 209 5 Met vallen en opstaan terug naar de top: 2002-2013 De fractievoorzitters 319 Gesproken bronnen 321 Geraadpleegde literatuur 325 Namenregister 327 VOORAF e meeste mensen vinden politiek saai. De geschiedenis van een politieke partij moet dan wel helemaal slaapverwekkend zijn. Wie de politiek een beetje volgt, weet wel beter. Toch zijn veel boeken die politiek als onderwerp hebben inderdaad saai om te lezen. Uitgangspunt bij het boek dat u nu in handen hebt, was om de geschiedenis van de WD-fractie in de Tweede Kamer zodanig op te schrijven, dat het trekjes van een politieke thriller krijgt. -

De Rote Armee Fraktion in Het Nederlandse Parlementaire Debat

“Zoals bekend, zijn dat gewapende overvallers, misdadigers.” Infame Misdrijven: De Rote Armee Fraktion in het Nederlandse parlementaire debat Master Scriptie, History PCNI: Political Debate Niels Holtkamp S0954055 Begeleider: Prof. Dr. H. te Velde Universiteit Leiden 01 juli 2019 [email protected] +31654938262 Kort Rapenburg 6A 2311 GC Leiden 2 1 “Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft, mag zusehn, dass er nicht dabei zum Ungeheuer wird. Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse (1886) 1 Titel naar uitspraak van Marcus Bakker (CPN), Handelingen Tweede Kamer 1973 – 1974, 4 september, 4604. ‘Infame misdrijven’ naar Theo van Schaik (KVP), Handelingen Tweede Kamer 1975 – 1976 12 februari, 2806. Afbeelding voorblad: Ton Schuetz/ANP. De ravage rond een telefooncel in Amsterdam Osdorp, waar bij een arrestatie in 1977 twee RAF leden en drie agenten gewond raakten, door vuurwapens en een handgranaat. 3 Inhoudsopgave “Zoals bekend, zijn dat gewapende overvallers, misdadigers.” .................................... 1 Afkortingen .................................................................................................................... 4 Deel 1 ............................................................................................................................. 5 De Rote Armee Fraktion en het Nederlandse parlementaire debat ................................ 6 Historiografie ............................................................................................................ -

Lijst Van Gevallen En Tussentijds Vertrokken Wethouders Over De Periode 2002-2006, 2006-2010, 2010-2014, 2014-2018

Lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders Over de periode 2002-2006, 2006-2010, 2010-2014, 2014-2018 Inleiding De lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders verschijnt op de website van De Collegetafel als bijlage bij het boek Valkuilen voor wethouders, uitgegeven door Boombestuurskunde Den Haag. De lijst geeft een overzicht van alle gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders in de periode 2002 tot en met 2018. Deze lijst van gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders betreft de wethouders die vanwege een politieke vertrouwensbreuk tijdelijk en/of definitief ten val kwamen tijdens de collegeperiode (vanaf het aantreden van de wethouders na de collegevorming tot het einde van de collegeperiode) en van wethouders die om andere redenen tussentijds vertrokken of voor wie het wethouderschap eindigde voor het einde van de reguliere collegeperiode. De valpartijen van wethouders zijn in deze lijst benoemd als gevolg van een tijdelijke of definitieve politieke vertrouwensbreuk, uitgaande van het vertrekpunt dat een wethouder na zijn benoeming of wethouders na hun benoeming als lid van een college het vertrouwen heeft/hebben om volwaardig als wethouder te functioneren totdat hij/zij dat vertrouwen verliest dan wel het vertrouwen verliezen van de hen ondersteunende coalitiepartij(en). Of wethouders al dan niet gebruik hebben gemaakt van wachtgeld is geen criterium voor het opnemen van ten val gekomen wethouders in de onderhavige lijst. Patronen De cijfermatige conclusies en de geanalyseerde patronen in Valkuilen voor wethouders zijn gebaseerd op deze lijst van politiek (tijdelijk of definitief) gevallen en tussentijds vertrokken wethouders. De reden van het ten val komen of vertrek is in de lijst toegevoegd zodat te zien is welke bijvoorbeeld politieke valpartijen zijn. -

Rondom De Nacht Van Schmelzer Parlementaire Geschiedenis Van Nederland Na 1945

Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945 Deel 1, Het kabinet-Schermerhorn-Drees 24 juni 1945 – 3 juli 1946 door F.J.F.M. Duynstee en J. Bosmans Deel 2, De periode van het kabinet-Beel 3 juli 1946 – 7 augustus 1948 door M.D. Bogaarts Deel 3, Het kabinet-Drees-Van Schaik 7 augustus 1948 – 15 maart 1951 onder redactie van P.F. Maas en J.M.M.J. Clerx Deel 4, Het kabinet-Drees II 1951 – 1952 onder redactie van J.J.M. Ramakers Deel 5, Het kabinet-Drees III 1952 – 1956 onder redactie van Carla van Baalen en Jan Ramakers Deel 6, Het kabinet-Drees IV en het kabinet-Beel II 1956 – 1959 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Peter van der Heiden Deel 7,Hetkabinet-DeQuay 1959 – 1963 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Jan Ramakers Deel 8, De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963 – 1967 onder redactie van Peter van der Heiden en Alexander van Kessel Stichting Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Den Haag Stichting Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945, Deel 8 Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963-1967 PETER VAN DER HEIDEN EN ALEXANDER VAN KESSEL (RED.) Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis Auteurs: Anne Bos Charlotte Brand Jan Willem Brouwer Peter van Griensven PetervanderHeiden Alexander van Kessel Marij Leenders Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Hilde Reiding Met medewerking van: Mirjam Adriaanse Miel Jacobs Teun Verberne Jonn van Zuthem Boom – Amsterdam Afbeelding omslag: Cals verlaat de Tweede Kamer na de val van zijn kabinet in de nacht van 13 op 14 oktober 1966.[anp] Omslagontwerp: Mesika Design, Hilversum Zetwerk: Velotekst (B.L. -

Loe De Jong 1914-2005

boudewijn smits Loe de Jong 1914-2005 Historicus met een missie bijlagen 8 tot en met 11 Boom Amsterdam inhoud bijlage 8 NOTEN Inleiding 5 Hoofdstuk 1 7 Hoofdstuk 2 19 Hoofdstuk 3 35 Hoofdstuk 4 53 Hoofdstuk 5 70 Hoofdstuk 6 82 Hoofdstuk 7 100 Hoofdstuk 8 111 Hoofdstuk 9 119 Hoofdstuk 10 131 Hoofdstuk 11 141 Hoofdstuk 12 154 Hoofdstuk 13 166 Hoofdstuk 14 178 Hoofdstuk 15 190 Hoofdstuk 16 200 Hoofdstuk 17 215 Hoofdstuk 18 223 Hoofdstuk 19 234 Hoofdstuk 20 243 Hoofdstuk 21 256 Hoofdstuk 22 266 Hoofdstuk 23 272 Hoofdstuk 24 288 Hoofdstuk 25 301 Hoofdstuk 26 315 Hoofdstuk 27 327 Hoofstuk 28 339 Hoofstuk 29 350 Hoofdstuk 30 360 Slotbeschouwing 371 bijlage 9 english summery 373 bijlage 10 geÏnterVIEWDE Personen 383 bijlage 11 geraadPleegde arChieVen 391 bijlage 8 NOTEN inleiding 1 Ernst H. Kossmann, ‘Continuïteit en discontinuïteit in de naoorlogse geschiedenis van Nederland’, Ons Erfdeel 28, nr. 5 (1985): 659-668, aldaar 660. 2 Een ander monumentaal werk is A study of History (Oxford 1934-1961) van de Britse historicus Arnold Toynbee dat in to- taal 12 delen omvat en meer dan 7000 bladzijden telt. 3 De Jongs oeuvre telt bij benadering 46.500 bladzijden. Zijn journalistiek werk: 24.742 blz. Specificatie: De Groene Am- sterdammer (februari 1937-mei 1940), circa 8000 blz.; Radio Oranje (juli 1940-augustus 1945), inclusief de geallieerde strooibladen De Wervelwind en De Vliegende Hollander en vanaf de bevrijding, Herrijzend Nederland, circa 10.000 blz.; zijn verzetstitel Holland fights the Nazis (1940): 138 blz. en de vierdelige reeks Je maintiendrai (1940-1944) exclusief bijlagen: 1447 blz.; 21 jaar buitenlandrubriek Vrij Nederland (van 1949 tot 1969): 5000 blz. -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2000 Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2000 Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer J.J.M. Ramakers W.P. Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: a n i\ D en Haag Vormgeving omslag: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zervverk: Velotekst (B.I.. van Popcring), Den Haag Druk en afwerking: Wilco b.v., Amersfoort Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht n desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, dan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever. © 2000 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or anv other means without written permission from the publisher. isb n 90 iz 08860 7 ISSN 1566-5054 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 A rtikelen 11 Gerard Visscher, Staatkundige vernieuwing in de twintigste eeuw: vechten tegen de bierkaai? 12 Patrick van Schie, Pijnlijke principes. De liberalen en de grondwetsherziening van 1917 28 Bert van den Braak, Met de tijd meegegaan. Eerste Kamer van bolwerk van de Kroon tot bolwerk van de burgers 44 Peter van der Heiden en Jacco Pekelder, De mythe van de dualistische jaren vijftig 61 J.A. van Kemenade, Een partijloze democratie? 73 Menno de Bruyne, Parlement en monarchie: preuts of present? 83 Peter van der Heiden, ‘Uniek in de wereld, maar wel veel gezeur.’ Vijftig jaar parlementaire bemoeienis met de televisie 96 Egodocument 115 Paid van der Steen, ‘Het aldergrootste gruwlyck quaet.’ Onderwijsminister Cals en zijn mammoetgedicht (1961) 116 Interview s 127 Carla van Baaien en Jan Willem Brouwer, ‘Van levensbelang is het niet voor d66.’ Thom de Graaf over het monarchiedebat 128 Willem Breedveld, Het is mooi geweest met Paars. -

De Feiten in De Tijd Gezien Vanaf Mijn

Aantekenen Aan het Landelijk Parket Rotterdam T.a.v. mr. G.W. van der Brug Hoofdofficier van Justitie Posthumalaan 74, 3072 AG Rotterdam Datum: 27 februari 2011 Ons kenmerk: NCF/EKC/270211/AG Betreft: - A.M.L. van Rooij, ‟t Achterom 9, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - A.M.L. van Rooij, als acoliet voor de RK Kerk H. Martinus Olland (Sint-Oedenrode); - J.E.M. van Rooij van Nunen, ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Camping en Pensionstal „Dommeldal‟ (VOF), gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9-9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Van Rooij Holding B.V., gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode; - Ecologisch Kennis Centrum B.V., gevestigd op ‟t Achterom 9a, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode, - Philips Medical Systems Nederland B.V., namens deze safety manager A.M.L. van Rooij, Veenpluis 4-6, 5684 PC te Best: - Politieke partij De Groenen, namens deze A.M.L. van Rooij als lijsttrekker van De Groenen in Sint-Oedenrode, ‟t Achterom 9, 5491 XD, Sint-Oedenrode, - Verbeek, Erik, Seovacki Put 43, KR-34550, Pakrac (Kroatie) - No Cancer Foundation, Paul Bellefroidlaan 16, 3500 Hasselt (België) Strafaangifte tegen: - de Raad van State met Vice-President H.D. Tjeenk Willink - de Staat der Nederlanden als rechtspersoon - Frank Houben (CDA), kamerheer en persoonlijke vriend van Koningin Beatrix; - alle huidige ministers in Kabinet-Rutte, waaronder met name Minister P.H. Donner (CDA) van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties. - alle nog in leven zijnde ministers en staatsecretarissen vanaf kabinet De Quay (21 april 1962) tot op heden Kabinet Rutte. - alle voormalige en huidige betrokken ministers, staatssecretarissen, vertegenwoordigers van VROM-inspectie, Unie van Waterschappen, Vereniging van de Nederlandse Gemeenten, Interprovinciaal Overleg, Openbaar Ministerie, College van Procureurs- generaal die zich hebben verenigd in het BLOM. -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in De Politiek

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in de politiek Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Nieuwkomers in de politiek Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer P.G.T.W. van Griensven J.J.M. Ramakers W.R Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: Hollandse Hoogte Vormgeving omslag: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zetwerk: Wil van Dam, Utrecht Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © 2002, Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, clan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. isbn 90 12 09574 3 issn 1566-5054 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen 9 Paul Lucardie, Van profeten en zwepen, regeringspartners en volkstribunen. Een beschouwing over de opkomst en rol van nieuwe partijen in het Nederlandse poli tieke bestel 10 Koen Vossen, Dominees, rouwdouwers en klungels. Nieuwkomers in de Tweede Kamer 1918-1940 20 Marco Schikhof, Opkomst, ontvangst en ‘uitburgering’ van een nieuwe partij en een nieuwe politicus. Ds’ 70 en Wim Drees jr. 29 Anne Bos en Willem Breedveld, Verwarring en onvermogen. De pers, de politiek en de opkomst van Pim Fortuyn 39 Jos de Beus, Volksvertegenwoordigers van ver. -

University of Groningen Jelle Zal Wel Zien Harmsma, Jonne

University of Groningen Jelle zal wel zien Harmsma, Jonne DOI: 10.33612/diss.67125602 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Harmsma, J. (2018). Jelle zal wel zien: Jelle Zijlstra, een eigenzinnig leven tussen politiek en economie. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. https://doi.org/10.33612/diss.67125602 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 26-09-2021 Jelle zal wel zien Jelle zal wel zien_150x230_proefschrift.indd 1 31-10-18 17:41 Jelle zal wel zien_150x230_proefschrift.indd 2 31-10-18 17:41 Jelle zal wel zien Jelle Zijlstra, een eigenzinnig leven tussen politiek en economie Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnif cus prof. -

Expertise 2012 08

Praktisch visieblad voor hoger onderwijs jaargang 6 | oktober 2012 | 8 Marjon Aker over Academische Vrijheid Arne Horst over EduGroepen Thema: De toekomstige minister van Onderwijs 1 jaargang 6 | oktober 2012 | 8 jaargang 6 | oktober 2012 | 8 In dit nummer Colofon Voorwoord Over Expertise Uitgever Pagina 4 Al jaren horen we geluiden uit het hoger- Mathieu Moons De academische vrijheid onderwijsveld dat er behoefte is aan één [email protected] platform voor uitwisseling van kennis, ervaring, Wat wil je bereiken en het Almensch kerkje ideeën en methodieken. Die functie gaan we Vormgeving met Expertise, praktisch visieblad voor hoger Mevrouw Lynch, Eindhoven Pagina 9 onderwijs, vervullen. We willen een mooi blad De kop eraf... maken dat er toe doet door mensen aan het Druk met je boodschap? woord te laten die met belangrijke initiatieven puntscherp, Eindhoven Pagina 14 bezig zijn, die ergens over nagedacht hebben en met hun inzichten de wereld verder helpen. Abonnementen Monitor Vrouwelijke Hoogleraren Met ander nieuws dan het gangbare, met U kunt zich op Expertise abonneren door te Afgelopen zomer heb ik me vaak verbaasd over de boodschap Ik vraag me af welk effect de besluitvorming rondom de 2012 interesante visies, filosofisch getinte artikelen mailen naar [email protected]. die mensen uitspreken, zonder dat ze zich bewust zijn van het langstudeerdersboete op de ontwikkeling van studenten zal en inspirerende verhalen van mensen die het Prijzen: printversie: € 179,- excl. btw per jaar. effect van die boodschap. Een moeder in een speelgoedwinkel hebben. Welke boodschap ontvangen zij door het slingerbeleid Pagina 15 hoger onderwijs kennen en met commentaren Hiervoor ontvangt u: tien nummers in print, zegt tegen haar zoontje: ‘Alleen maar kijken met oogjes, niet met tijdens de politieke crisis? En is dat wel het effect dat politici willen Thema: de toekomstige minister op actuele ontwikkelingen. -

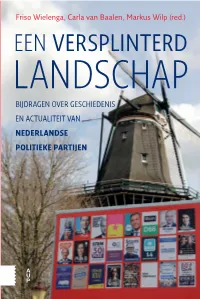

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Emotie in De Politiek

r - - Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis ^ 2003 Emotie in de politiek / Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2003 Emotie in de politiek Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Emotie in de politiek Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer P.G.T.W. van Griensven J.J.M. Ramakers W.R Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: Roel Rozenburg Vormgeving omslag en binnenwerk: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zetwerk: Wil van Dam, Utrecht Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © 2003, Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, dan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever (www.sdu.nl). Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. isbn 90 12 09 9 6 7 6 issn 15 6 6 -5 0 5 4 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen 11 Retnieg Aerts, Emotie in de politiek. Over politieke stijlen in Nederland sinds 1848 12 Rady B. Andeweg en Jacques Thomassen, Tekenen aan de wand? Kamerleden, kiezers en commentatoren over de kwaliteit van de parlementaire democratie in Nederland 26 Carla van Baaien, Cry if I want to? Politici in tranen 36 Ulla Jansz, Hartstocht en opgewondenheid. Kamerdebatten over mensenrechten in de koloniën rond 1850 47 Marij Leenders, ‘Gesol met de rechten van vervolgde mensen.’ Emoties in het asieldebat 1938-1999 57 Carla Hoetink, Als de hamer valt.