Requirements Department of Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

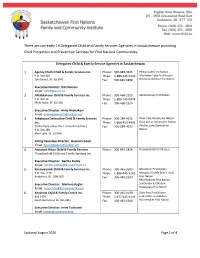

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Wollaston Road

WOLLASTON LAKE ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Biophysical Environment 4.0 Biophysical Environment 4.1 INTRODUCTION This section provides a description of the biophysical characteristics of the study region. Topics include climate, geology, terrestrial ecology, groundwater, surface water and aquatic ecology. These topics are discussed at a regional scale, with some topics being more focused on the road corridor area (i.e., the two route options). Information included in this section was obtained in full or part from direct field observations as well as from reports, files, publications, and/or personal communications from the following sources: Saskatchewan Research Council Canadian Wildlife Service Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board Reports Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History W.P. Fraser Herbarium Saskatchewan Environment Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre Environment Canada Private Sector (Consultants) Miscellaneous publications 4.2 PHYSIOGRAPHY Both proposed routes straddle two different ecozones. The southern portion is located in the Wollaston Lake Plain landscape area within the Churchill River Upland ecoregion of the Boreal Shield ecozone. The northern portion is located in the Nueltin Lake Plain landscape area within the Selwyn Lake Upland ecoregion of the Taiga Shield ecozone (Figure 4.1). (SKCDC, 2002a; Acton et al., 1998; Canadian Biodiversity, 2004; MDH, 2004). Wollaston Lake lies on the Precambrian Shield in northern Saskatchewan and drains through two outlets. The primary Wollaston Lake discharge is within the Hudson Bay Drainage Basin, which drains through the Cochrane River, Reindeer Lake and into the Churchill River system which ultimately drains into Hudson Bay. The other drainage discharge is via the Fond du Lac River to Lake Athabasca, and thence to the Arctic Ocean. -

Pictographs in Northern Saskatchewan: Vision Quest

PICTOGRAPHS IN NORTHERN SASKATCHEWAN: VISION QUEST AND PAWAKAN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon by Katherine A. Lipsett April, 1990 The author claims copyright. Use shall not be made of the material contained herein without proper acknowledgement, as indicated on the following page. The author has agreed that the Library, University of Saskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection. Moreover, the author has agreed that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesis. Copying or publication or any other use of the thesis for financial gain without approval by the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission is prohibited. Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N OWO i ABSTRACT Pictographs in northern Saskatchewan have been linked to the vision quest ritual by Rocky Cree informants. -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

MRBB4 Reportcol 2.7.6

Mackenzie River Basin State of the Aquatic Ecosystem Report 2003 8. Recent & Anticipated Developments Traditionally, state of the environment reports look back in time to assess the condition of the Industrial Developments environment and whether it has changed. However, there is also value in looking forward to anticipate what some of the major The Oil and Gas Industry environmental challenges will be in the coming The oil and gas industry will continue to expand years and to assess whether public and private in most jurisdictions in the Mackenzie River Basin. sector programs will be adequate to deal with Exploration, seismic activity, the development of those challenges. In this section of the report, new wells and pipeline expansions will continue in the Mackenzie River Basin Board examines the southern part of the basin. Exploration and some of the major industrial developments, seismic activity have increased in the Northwest environmental issues and initiatives that could Territories but have not yet reached the levels of affect the Mackenzie River Basin over the course the early 1970s. Land disturbance and the removal of the next few years. Specifically, it considers of vegetation are usually associated with these industrial developments that may occur in the activities. basin and public and private sector The proposed Mackenzie Gas Project (MGP) environmental initiatives. may stimulate further petroleum exploration and lead to development of gas reserves in the Mackenzie Delta and other parts of the western NWT. A major component of the MGP is a proposed pipeline that would move gas to southern markets 195 through the Mackenzie River Valley. -

The Cultural Ecology of the Chipewyan / by Donald Stewart Mackay.

ThE CULTURAL ECOLOGY OF TkE CBIPE%YAN UONALD STEhAkT MACKAY b.A., University of british Columbia, 1965 A ThESIS SUBMITTED IN PAhTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE HEObIRCMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the department of Sociology and Anthropology @ EONALD STECART MACKAY, 1978 SIMON F hAShR UNlVERSITY January 1978 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in, part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : Donald Stewart Mackay Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Cultural Ecology of the Chipewyan Examining Cormnit tee : Chairman : H. Sharp Senior Supervisor- - N. Dyck C.B. Crampton . Fisher Departme'nt of Biological Sciences / ,y/y 1 :, Date Approved: //!,, 1 U The of -- Cultural Ecology .- --------the Chipewyan ----- .- ---A <*PI-: (sign-ir ~re) - Donald Stewart Mackay --- (na~t) March 14, 1978. (date ) AESTRACT This study is concerned with the persistence of human life on the edge of the Canadian Barren Grounds. The Chipewyan make up the largest distinct linguistic and cultural group and are the most easterly among the Northern Athapaskan Indians, or Dene. Over many centuries, the Chipewyan have maintained a form of social life as an edge-of-the-forest people and people of the Barren Grounds to the west of Hudson Bay. The particular aim of this thesis is to attempt, through a survey of the ecological and historical 1iterature , to elucidate something of the traditional adaptive pattern of the Chipewyan in their explcitation of the subarc tic envirorient . Given the fragmentary nature of much of the historical evidence, our limited understanding of the subarctic environment, and the fact that the Chipewyan oecumene (way of looking at life) is largely denied to the modern observer, we acknowledge that this exercise in ecological and historical reconstruction is governed by serious hazards and limitations. -

Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Lena May Seegerts Email: [email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306 845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Phone: 306 845-1427 Box 368 Fax: 306 845-1428 Turtleford, SK S0M 2Y0 Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

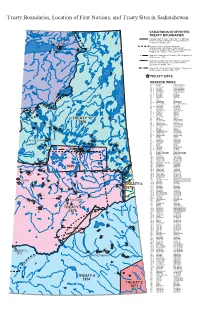

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Recording the Reindeer Lake

CONTEXTUALIZING THE REINDEER LAKE ROCK ART A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Perry Blomquist © Copyright Perry Blomquist, April 2011. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5B1 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT The rock art that is found in the region of Reindeer Lake, Saskatchewan is part of a larger category of rock art known as the Shield Rock Art Tradition. -

2017 Anglers Guide.Cdr

Saskatchewan Anglers’ Guide 2017 saskatchewan.ca/fishing Free Fishing Weekends July 8 and 9, 2017 February 17, 18 and 19, 2018 Minister’s Message I would like to welcome you to a new season of sport fishing in Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan's fishery is a priceless legacy, and it is the ministry's goal to maintain it in a healthy, sustainable state to provide diverse benefits for the province. As part of this commitment, a portion of all angling licence fees are dedicated to enhancing fishing opportunities through the Fish and Wildlife Development Fund (FWDF). One of the activities the FWDF supports is the operation of Scott Moe the Saskatchewan Fish Culture Station, which plays a Minister of Environment key role in managing a number of Saskatchewan's sport fisheries. To meet the province's current and future stocking needs, a review of the station's aging infrastructure was recently completed, with a multi-year plan for modernization and refurbishment to begin in 2017. In response to the ongoing threat of aquatic invasive species, the ministry has increased its prevention efforts on several fronts, including increasing public awareness, conducting watercraft inspections and monitoring high- risk waters. I ask everyone to continue their vigilance against the threat of aquatic invasive species by ensuring that your watercraft and related equipment are cleaned, drained and dried prior to moving from one body of water to another. Responsible fishing today ensures fishing opportunities for tomorrow. I encourage all anglers to do their part by becoming familiar with this guide and the rules and regulations that pertain to your planned fishing activity.