From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uranium City, Black Lake, Camsell Portage, Fond Du Lac, Stony Rapids, and Wollaston/Hatchet Lake

CanNorth 2015 AthabascaUranium Working City Group Environmental Monitoring Program ABOUT THE AWG PROGRAM The Athabasca Working Group (AWG) environmental monitoring program began in the Athabasca region of northern Saskatchewan in 2000. The program provides residents with opportunities to test the environment around their communities for parameters that could come from uranium mining and milling operations. These parameters can potentially be spread by water flowing from lakes near the uranium operations, and small amounts may also be spread through the air. In order to address local residents’ concerns, lakes, rivers, plants, wildlife, and air quality are tested each yeah near the northern communities of Uranium City, Black Lake, Camsell Portage, Fond du Lac, Stony Rapids, and Wollaston/Hatchet Lake. The types of plants and animals selected, the locations chosen for sampling, and the sample collections were carried out by, or with the help of, northern community members. The purpose of this brochure is to inform the public of the 2015 environmental monitoring program results in the Uranium City area. STUDY AREA Water, sediment, and fish were sampled from a reference site and a potential exposure site in the Uranium City area in 2015. Fredette Lake was chosen as the reference site because it is not influenced by uranium operations. Black Bay of Lake Athabasca (Black Bay) is referred to as the potential exposure site because it is located downstream of the active uranium operations in northern Saskatchewan. Air quality is monitored at two locations near the community of Uranium City and plant and wildlife samples are collected each year near the community when available. -

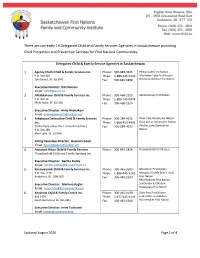

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Wollaston Road

WOLLASTON LAKE ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Biophysical Environment 4.0 Biophysical Environment 4.1 INTRODUCTION This section provides a description of the biophysical characteristics of the study region. Topics include climate, geology, terrestrial ecology, groundwater, surface water and aquatic ecology. These topics are discussed at a regional scale, with some topics being more focused on the road corridor area (i.e., the two route options). Information included in this section was obtained in full or part from direct field observations as well as from reports, files, publications, and/or personal communications from the following sources: Saskatchewan Research Council Canadian Wildlife Service Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board Reports Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History W.P. Fraser Herbarium Saskatchewan Environment Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre Environment Canada Private Sector (Consultants) Miscellaneous publications 4.2 PHYSIOGRAPHY Both proposed routes straddle two different ecozones. The southern portion is located in the Wollaston Lake Plain landscape area within the Churchill River Upland ecoregion of the Boreal Shield ecozone. The northern portion is located in the Nueltin Lake Plain landscape area within the Selwyn Lake Upland ecoregion of the Taiga Shield ecozone (Figure 4.1). (SKCDC, 2002a; Acton et al., 1998; Canadian Biodiversity, 2004; MDH, 2004). Wollaston Lake lies on the Precambrian Shield in northern Saskatchewan and drains through two outlets. The primary Wollaston Lake discharge is within the Hudson Bay Drainage Basin, which drains through the Cochrane River, Reindeer Lake and into the Churchill River system which ultimately drains into Hudson Bay. The other drainage discharge is via the Fond du Lac River to Lake Athabasca, and thence to the Arctic Ocean. -

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Denison Mines Corp. May 2019 WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Project Summary English – Page ii French – Page x Dene – Page xx Cree – Page xxviii PAGE i WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Summary Wheeler River Project The Wheeler River Project (Wheeler or the Project) is a proposed uranium mine and processing plant in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is located in a relatively undisturbed area of the boreal forest about 4 km off of Highway 914 and approximately 35 km north-northeast of the Key Lake uranium operation. Wheeler is a joint venture project owned by Denison Mines Corp. (Denison) and JCU (Canada) Exploration Company Ltd. (JCU). Denison owns 90% of Wheeler and is the operator, while JCU owns 10%. Denison is a uranium exploration and development company with interests focused in the Athabasca Basin region of northern Saskatchewan, Canada with a head office in Toronto, Ontario and technical office in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Historically Denison has had over 50 years of uranium mining experience in Saskatchewan, Elliot Lake, Ontario, and in the United States. Today, the company is part owner (22.5%) of the McClean Lake Joint Venture which includes the operating McClean Lake uranium mill in northern Saskatchewan. To advance the Project, Denison is applying an innovative approach to uranium mining in Canada called in situ recovery (ISR). The use of ISR mining at Wheeler means that there will be no need for a large open pit mining operation or multiple shafts to access underground mine workings; no workers will be underground as the ISR process is conducted from surface facilities. -

True North // September 2017

True North // September 2017 cameco in northern saskatchewan Cameco partners with the Red Cross to support Pelican Narrows evacuees (p.2) WINTER Surviving off 2015 Land and Water Fond du Lac Canoe Quest is a Success Far From Home Red Cross and Cameco employees delivered baby strollers to young families from northeastern Saskatchewan while they were evacuated to Prince Albert and Saskatoon during the wildfires earlier this fall. “Once again, Cameco came through to help those Cameco proud to evacuated in northern Saskatchewan,” said Cindy support evacuees Fuchs, Vice-President of the Canadian Red Cross in during fires Saskatchewan. “We are so thankful for Cameco’s support – it makes a world of difference for people forced from their homes.” Wildfires forced more than 2,700 people from the Cree communities of Pelican Narrows and Sandy Bay in late August. The evacuation ban was lifted September 13. During that time evacuees stayed in Prince Albert and Saskatoon with the aid of the Red Cross. Cameco was proud to partner with the organization and provided baby strollers, movie passes and food to make the stay more comfortable. Cameco also contributed $25,000 to the Red Cross’s Red Gala. Proceeds from the gala help support disaster relief. source: Government of Saskatchewan Facebook page page 2 True North // September 2017 Fond du Lac Youth Canoe Quest imparts important traditional skills The participants in the Fond du Lac also visited the basecamp to perform, Toutsaint says the experience made Canoe Quest met with stunning as well as other members who wanted such an impression that the community sunrises for five days at the beginning to cheer the group along. -

Creighton-Flin Flon

Flin Flon Domain of Saskatchewan – Dataset Descriptions The Flin Flon domain hosts one of the most prolific Precambrian volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) districts in the world, with over 160 million tonnes of ore produced from at least 28 deposits in Saskatchewan and Manitoba since the start of the 20th century. Situated in the Reindeer Zone of the of the Trans-Hudson Orogen, rocks of this domain comprise dominantly metamorphosed and polydeformed volcanoplutonic terranes with subordinate siliciclastic sedimentary sequences. Volcanic rocks vary in composition throughout the domain and were originally emplaced in a variety of tectonic settings, including island arc(s), arc rift, ocean floor, and ocean pleateau. The VMS deposits are hosted primarily by Paleoproterozoic juvenile arc rocks in one of several defined lithotectonic assemblages. The datasets provided for this area are located within a ~12,000 km2 area of the Flin Flon Domain of Saskatchewan that contains several past producing base metal mines and a multitude of known mineral occurrences. The northern quarter of the area is underlain by exposed Precambrian Shield, whereas the southern three-quarters consists of Precambrian basement situated beneath up to 200 metres of undeformed, Phanerozoic sedimentary rocks. The sedimentary cover in this southern portion makes exploration of the Precambrian rocks particularly challenging. The datasets provided for this area consist of: (i) airborne geophysical survey data, and (ii) multiple GIS datasets from the exposed Precambrian Shield and/or the buried Precambrian basement and/or the Phanerozoic sedimentary cover. The geophysical data comprises digital data for 22 airborne surveys including industry-derived data submitted to the Saskatchewan Geological Survey through assessment work reports, and surveys funded by provincial and federal governments. -

Pictographs in Northern Saskatchewan: Vision Quest

PICTOGRAPHS IN NORTHERN SASKATCHEWAN: VISION QUEST AND PAWAKAN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon by Katherine A. Lipsett April, 1990 The author claims copyright. Use shall not be made of the material contained herein without proper acknowledgement, as indicated on the following page. The author has agreed that the Library, University of Saskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection. Moreover, the author has agreed that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesis. Copying or publication or any other use of the thesis for financial gain without approval by the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission is prohibited. Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N OWO i ABSTRACT Pictographs in northern Saskatchewan have been linked to the vision quest ritual by Rocky Cree informants. -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: a Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan

University of Alberta Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: A Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan by Bryn Alan Politylo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Rural Sociology Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Bryn Alan Politylo Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Recently northwest Saskatchewan has seen a rapid push towards large-scale development corresponding with a shifting political economy in the province. For the rights- bearing Métis people of northwest Saskatchewan this shift significantly influences provincial environmental governance, which affects the agency of Métis people to participate in natural resource management and decision-making in the region. To examine the agency and power of Métis communities in provincial natural resource management and decision-making, qualitative methods and a comparative case study of three Métis communities were used to analyze and interpret the social spaces that Métis people occupy in provincial environmental governance. -

Uranium City

Community Meeting Record January 29 – Feb 1, 2019 Uranium City – January 29, 2019 Attendees • Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) o Ian Wilson o David Sanscartier o Chris Reid o Robyn Morris o John Sprague o Jennifer Brown • Mina Patel (Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC)) • Jaynine McCrea (Fond du Lac Nuna Joint Venture (FDLNJV)) • Dean Classen (Uranium City Contracting (UCC)) • Kyle Remus (QMPoints) • Glen Strong (QMPoints) • Emily Jones (Translator) Agenda 1. Prayer 2. Lunch 3. Video 4. Satellite Sites (David) 5. Uranium City Contracting (Dean) 6. Gunnar Overview (Chris) 7. Gunnar Other Site Aspects (Chris) 8. Gunnar Other Site Aspects (QMPoints) 9. Gunnar Tailings (Robyn) 10. Gunnar Tailings (Jaynine) 11. Lorado (Ian) 12. Photo Contest (John) 13. CNSC (Mina) 14. Prize Draws and Close Discussion Satellite Sites Q. Looking at the criteria you have for workers on the project, do you have criteria for a certain number of or percentage of women? A. There is nothing specific, but the wording states that the process is to be all inclusive and non- discriminatory. Q. What about the criteria for equipment usage? Is that including Indigenous? A. It is not specific to Indigenous. The second point is for the equipment, not the operator. 1 Community Meeting Record January 29 – Feb 1, 2019 Q. How is the gamma survey done? Is it on contact? A. The survey is done one meter above the ground. Q. How much soil is required to cover the gamma spots? What is required for protection? A. We are putting 30-50 cm over the hot spots, which is more than enough. -

New Results from Mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan

Stratigraphy, Structure, and Silicification: New Results From Mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan Kate MacLachlan MacLachlan (2006): Stratigraphy, structure, and silicification: new results from mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan; in Summary of Investigations Volume 2, 2006, Saskatchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Industry Resources, Misc. Rep. 2006-4.2, CD-ROM, Paper A-9, 25p. Abstract Two areas in the Flin Flon mining camp were mapped at a scale of 1:5000, one area between Douglas Lake and West Arm Road on the west limb of the Beaver Road Anticline, and the other on the peninsula between Green Lake and Phantom Lake. In the Douglas Lake area, mapping was undertaken in the hanging wall of the west-younging, felsic-dominated Myo member of the Flin Flon formation. Significant findings include, an extrusive felsic unit above the upper contact of the Myo member, abundant peperite at several stratigraphic levels, an up to 100 m wide zone of semi-conformable silicification, and pervasive sinistral shearing that post-dates the Phantom Intrusive Suite. In the Green Lake Peninsula area, three fault-bounded successions with opposing younging directions were recognized. The easternmost succession, east of the newly defined Burley Lake Fault (a modified version of the Phantom Lake Fault), is part of the west-younging Louis formation on the east limb of the Burley Lake Syncline. The east-younging succession between the Burley Lake and Green Lake faults comprises a large component of fine- grained mafic volcaniclastic rocks intercalated with aphyric and plagioclase ± pyroxene porphyritic flows, and is tentatively correlated with the Hidden formation. -

MRBB4 Reportcol 2.7.6

Mackenzie River Basin State of the Aquatic Ecosystem Report 2003 8. Recent & Anticipated Developments Traditionally, state of the environment reports look back in time to assess the condition of the Industrial Developments environment and whether it has changed. However, there is also value in looking forward to anticipate what some of the major The Oil and Gas Industry environmental challenges will be in the coming The oil and gas industry will continue to expand years and to assess whether public and private in most jurisdictions in the Mackenzie River Basin. sector programs will be adequate to deal with Exploration, seismic activity, the development of those challenges. In this section of the report, new wells and pipeline expansions will continue in the Mackenzie River Basin Board examines the southern part of the basin. Exploration and some of the major industrial developments, seismic activity have increased in the Northwest environmental issues and initiatives that could Territories but have not yet reached the levels of affect the Mackenzie River Basin over the course the early 1970s. Land disturbance and the removal of the next few years. Specifically, it considers of vegetation are usually associated with these industrial developments that may occur in the activities. basin and public and private sector The proposed Mackenzie Gas Project (MGP) environmental initiatives. may stimulate further petroleum exploration and lead to development of gas reserves in the Mackenzie Delta and other parts of the western NWT. A major component of the MGP is a proposed pipeline that would move gas to southern markets 195 through the Mackenzie River Valley.