Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: a Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Denison Mines Corp. May 2019 WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Project Summary English – Page ii French – Page x Dene – Page xx Cree – Page xxviii PAGE i WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Summary Wheeler River Project The Wheeler River Project (Wheeler or the Project) is a proposed uranium mine and processing plant in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is located in a relatively undisturbed area of the boreal forest about 4 km off of Highway 914 and approximately 35 km north-northeast of the Key Lake uranium operation. Wheeler is a joint venture project owned by Denison Mines Corp. (Denison) and JCU (Canada) Exploration Company Ltd. (JCU). Denison owns 90% of Wheeler and is the operator, while JCU owns 10%. Denison is a uranium exploration and development company with interests focused in the Athabasca Basin region of northern Saskatchewan, Canada with a head office in Toronto, Ontario and technical office in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Historically Denison has had over 50 years of uranium mining experience in Saskatchewan, Elliot Lake, Ontario, and in the United States. Today, the company is part owner (22.5%) of the McClean Lake Joint Venture which includes the operating McClean Lake uranium mill in northern Saskatchewan. To advance the Project, Denison is applying an innovative approach to uranium mining in Canada called in situ recovery (ISR). The use of ISR mining at Wheeler means that there will be no need for a large open pit mining operation or multiple shafts to access underground mine workings; no workers will be underground as the ISR process is conducted from surface facilities. -

True North // September 2017

True North // September 2017 cameco in northern saskatchewan Cameco partners with the Red Cross to support Pelican Narrows evacuees (p.2) WINTER Surviving off 2015 Land and Water Fond du Lac Canoe Quest is a Success Far From Home Red Cross and Cameco employees delivered baby strollers to young families from northeastern Saskatchewan while they were evacuated to Prince Albert and Saskatoon during the wildfires earlier this fall. “Once again, Cameco came through to help those Cameco proud to evacuated in northern Saskatchewan,” said Cindy support evacuees Fuchs, Vice-President of the Canadian Red Cross in during fires Saskatchewan. “We are so thankful for Cameco’s support – it makes a world of difference for people forced from their homes.” Wildfires forced more than 2,700 people from the Cree communities of Pelican Narrows and Sandy Bay in late August. The evacuation ban was lifted September 13. During that time evacuees stayed in Prince Albert and Saskatoon with the aid of the Red Cross. Cameco was proud to partner with the organization and provided baby strollers, movie passes and food to make the stay more comfortable. Cameco also contributed $25,000 to the Red Cross’s Red Gala. Proceeds from the gala help support disaster relief. source: Government of Saskatchewan Facebook page page 2 True North // September 2017 Fond du Lac Youth Canoe Quest imparts important traditional skills The participants in the Fond du Lac also visited the basecamp to perform, Toutsaint says the experience made Canoe Quest met with stunning as well as other members who wanted such an impression that the community sunrises for five days at the beginning to cheer the group along. -

Canoeingthe Clearwater River

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | The clearwater river To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 1-2 weeks canoeing the clearwater river 105 km History of the Clearwater River For years fur traders from the east tried in vain to find a route to Athabasca country. Things changed in 1778, when Peter Pond crossed The legendary Clearwater has it the 20 km Methye Portage from the headwaters of the east-flowing all—unspoiled wilderness, thrilling Churchill River to the eventual west-bound Clearwater River. Here whitewater, unparalleled scenery was the sought-after land bridge between the Hudson Bay and and inviting campsites with Arctic watersheds, opening up the vast Canadian north. Paddling the fishing outside the tent door. This Clearwater today, you not only follow in the wake of voyageurs with Canadian Heritage River didn’t their fur-laden birchbark canoes, but also a who’s who of northern merely play a role in history; it exploration, the likes of Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson, changed its very course. John Franklin and Peter Pond. Saskatoon Saskatoon Regina Regina • Canoeing Route • Vehicle Highway Broach Lake Patterson Lake n Forrest Lake Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 955 A T ALBER Fort McMurray Clearwater River Broach Lake Provincial Park Careen Lake Clearwater River Patterson Lake n Gordon Lake Forrest Lake La Loche Lac La Loche Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 155 Churchill Lake Peter Pond 955 Lake A SASKATCHEWAN Buffalo Narrows T ALBER Skull Canyon, Clearwater River Provincial Park. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

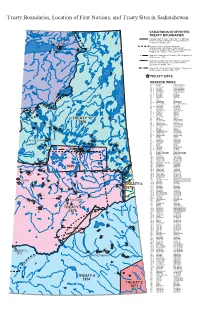

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Community Investment in the Pandemic: Trends and Opportunities

Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities Jonathan Huntington, Vice President Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations, Cameco January 6, 2021 A Cameco Safety Moment Recommended for the beginning of any meeting Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 2 Community investment in the pandemic: Trends • Demand - increase in requests • $1 million Cameco COVID Relief Fund: 581 applications, $17.5 million in requests • Immense competition for funding dollars • We supported 67 community projects across 40 different communities in SK Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 3 Successful applicants for Cameco COVID Relief Fund Organization Community Organization Community Children North Family Resource Center La Ronge The Generation Love Project Saskatoon Prince Albert Child Care Co-operative Association Prince Albert Lakeview Extended School Day Program Inc. Saskatoon Central Urban Metis Federation Inc. Saskatoon Delisle Elementary School -Hampers Delisle TLC Daycare Inc. Birch Hills English River First Nation English River Beauval Group Home (Shirley's Place) Beauval NorthSask Special Needs La Ronge Nipawin Daycare Cooperative Nipawin Leask Community School Leask Battlefords Interval House North Battleford Metis Central Western Region II Prince Albert Beauval Emergency Operations - Incident Command Beauval Global Gathering Place Saskatoon Northern Hamlet of Patuanak Patuanak Saskatoon YMCA Saskatoon Northern Settlement of Uranium City Uranium City -

Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects

TSX: CCO website: cameco.com NYSE: CCJ currency: Cdn (unless noted) 2121 – 11th Street West, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7M 1J3 Canada Tel: 306-956-6200 Fax: 306-956-6201 Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, April 30, 2020 . Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) is pleased to announce that the company is supporting 67 community projects in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan through its $1 million Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund. “There are so many communities and charitable groups hit hard by this pandemic, yet their services are needed now more than ever,” said Cameco president and CEO Tim Gitzel. “We are extremely happy to be able to help 67 of these organizations continue to do the vital work they do every day to keep people safe and supported through this unprecedented time.” Approved projects come from 40 Saskatchewan communities from Saskatoon to the province’s far north. A full listing can be found at the end of this release. Included in the support Cameco is providing are significant numbers of personal protective equipment (PPE) for northern Saskatchewan communities and First Nations – 10,000 masks, 7,000 pairs of gloves and 7,000 litres of hand sanitizer. Donations of supplies and money from nearly 100 Cameco employees augmented the company’s initial $1 million contribution. Cameco will move quickly to begin delivering this support to the successful applicants. “I’m proud of Cameco’s employees for stepping up yet again to support the communities where they live,” Gitzel said. “It happens every time we put out a call for help, a call for volunteers, a call to assist with any of our giving campaigns, and I can’t say enough about their generosity.” Announced on April 15, the Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund was open to applications from charities, not-for-profit organizations, town offices and First Nation band offices in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan that have been impacted by the pandemic. -

SPSA Annual Report 2020-21

Letters of Transmittal .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Agency Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 SPSA COVID-19 Response Highlights ............................................................................................................................. 6 Progress in 2020-21 ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 Strategy: Reduce the impact of emergencies by increasing community preparedness ................................ 8 Strategy: Prevent and mitigate emergencies through planning and partnerships ...................................... 10 Strategy: Deliver seamless public safety services......................................................................................... 12 Strategy: Enhance technology supports for public safety service providers and citizens ............................ 14 Strategy: Ensure the SPSA is a centre of excellence, providing programs and services that meet client needs ............................................................................................................................................................ 17 Strategy: Foster a safe, high-performing organization and -

The Night Sky

Tthën (Dëne) Acâhkosak (Cree) The Night Sky Shaun Nagy La Loche Community School La Loche, SK, Canada A unit in the series: Rekindling Traditions: Cross-Cultural Science and Technology Units Series Editor Glen Aikenhead University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK, Canada Tthën © College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada, 2000. You may freely adapt, copy, and distribute this material provided you adhere to the following conditions: 1. The copies are for educational purposes only. 2. You are not selling this material for a profit. You may, however, charge the users the cost of copying and/or reasonable administrative and overhead costs. 3. You will pay Cancopy for any content identified as “printed with Cancopy permission” in the normal way you pay Cancopy for photocopying copyrighted material. You are not allowed to adapt, copy, and distribute any of this material for profit without the written permission of the editor. Requests for such permission should be mailed to: Dr. Glen S. Aikenhead, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, 28 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 0X1, Canada. Tthën CURRICULUM CONNECTION Grades 8-11, astronomy OVERVIEW Aboriginal cosmology is validated through learning about the night sky from an Aboriginal point of view. This provides the context for learning astronomy concepts from Western science. Both knowledge systems, Aboriginal and Western, are explicitly acknowledged. Experiential learning is highlighted in both domains in this unit. Duration: about 2 to 3 weeks. FUNDING The CCSTU -

Phase 1 Geoscientific Desktop Preliminary Assessment, Terrain and Remote Sensing Study

Phase 1 Geoscientific Desktop Preliminary Assessment, Terrain and Remote Sensing Study NORTHERN VILLAGE OF PINEHOUSE, SASKATCHEWAN APM-REP-06144-0060 NOVEMBER 2013 This report has been prepared under contract to the NWMO. The report has been reviewed by the NWMO, but the views and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NWMO. All copyright and intellectual property rights belong to the NWMO. For more information, please contact: Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East, Sixth Floor Toronto, Ontario M4T 2S3 Canada Tel 416.934.9814 Toll Free 1.866.249.6966 Email [email protected] www.nwmo.ca PHASE 1 DESKTOP GEOSCIENTIFIC PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT TERRAIN AND REMOTE SENSING STUDY NORTHERN VILLAGE OF PINEHOUSE, SASKATCHEWAN November 2013 Prepared for: G.W. Schneider, M.Sc., P.Geo. Golder Associates Ltd. 6925 Century Ave, Suite 100 Mississauga, Ontario Canada L5N 7K2 Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East 6th Floor Toronto, Ontario Canada M4T 2S3 NWMO Report Number: APM-REP-06144-0060 Prepared by: D.P. van Zeyl, M.Sc. L.A. Penner, M.Sc., P.Eng., P.Geo. J.D. Mollard and Associates (2010) Limited 810 Avord Tower, 2002 Victoria Avenue Regina, Saskatchewan Canada S4P 0R7 Terrain Report, Pinehouse, Saskatchewan November 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In March 2012, the Northern Village of Pinehouse, Saskatchewan, expressed interest in continuing to learn more about the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) nine-step site selection process, and requested that a preliminary assessment be conducted to assess the potential suitability of the Pinehouse area for safely hosting a deep geological repository (Step 3). -

From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Érudit Article "From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects" David M. Quiring Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 17, n° 1, 2006, p. 151-178. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/016106ar DOI: 10.7202/016106ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 10:21 From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects DAVID M. QUIRING Abstract The election of the CCF in 1944 brought rapid change for the residents of northern Saskatchewan. CCF initiatives included encouraging northern aboriginals to trade their semi-nomadic lifestyles for lives in urban settings. The establishment of Kinoosao on Reindeer Lake provides an example of how CCF planners established new villages; community development processes excluded local people. -

Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority

Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority 2015- 16 Annual Report Cover photo “Bear Approaching” Green Lake This report is available in electronic format (PDF) online at www.kyrha.ca Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority Box 40, Buffalo Narrows, Saskatchewan S0M 0J0 Toll Free 1-866-274-8506 • Local (306) 235-2220 • Fax (306) 235-4604 www.kyrha.ca 2 Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority 2015 - 16 Annual Report Wholistic Health of Keewatin Yatthé Health Region Residents 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal .............................................. 5 Healthy People, Healthy Communities ...................8 Introduction ........................................................... 6 Provincial Health Regions Map ..............................9 Population by Age Group ......................................11 Alignment with Strategic Direction Population Pyramid ..............................................11 Alignment ............................................................... 8 Occupied Private Dwelling Characteristics ...........11 Strategic Direction and Goals ................................ 9 Patient Safety Occurrences ..................................15 Factors ................................................................. 11 KYRHA Facilities Map ..........................................17 KYRHA Home-Care Coverage Map .....................19 KYRHA Overview Service Utilization .................................................30 Organizational Changes ...................................... 14 Patient Safety .......................................................15