Recent Ethnographic Research—Upper Churchill River Drainage, Saskatchewan, Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

True North // September 2017

True North // September 2017 cameco in northern saskatchewan Cameco partners with the Red Cross to support Pelican Narrows evacuees (p.2) WINTER Surviving off 2015 Land and Water Fond du Lac Canoe Quest is a Success Far From Home Red Cross and Cameco employees delivered baby strollers to young families from northeastern Saskatchewan while they were evacuated to Prince Albert and Saskatoon during the wildfires earlier this fall. “Once again, Cameco came through to help those Cameco proud to evacuated in northern Saskatchewan,” said Cindy support evacuees Fuchs, Vice-President of the Canadian Red Cross in during fires Saskatchewan. “We are so thankful for Cameco’s support – it makes a world of difference for people forced from their homes.” Wildfires forced more than 2,700 people from the Cree communities of Pelican Narrows and Sandy Bay in late August. The evacuation ban was lifted September 13. During that time evacuees stayed in Prince Albert and Saskatoon with the aid of the Red Cross. Cameco was proud to partner with the organization and provided baby strollers, movie passes and food to make the stay more comfortable. Cameco also contributed $25,000 to the Red Cross’s Red Gala. Proceeds from the gala help support disaster relief. source: Government of Saskatchewan Facebook page page 2 True North // September 2017 Fond du Lac Youth Canoe Quest imparts important traditional skills The participants in the Fond du Lac also visited the basecamp to perform, Toutsaint says the experience made Canoe Quest met with stunning as well as other members who wanted such an impression that the community sunrises for five days at the beginning to cheer the group along. -

Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: a Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan

University of Alberta Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: A Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan by Bryn Alan Politylo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Rural Sociology Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Bryn Alan Politylo Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Recently northwest Saskatchewan has seen a rapid push towards large-scale development corresponding with a shifting political economy in the province. For the rights- bearing Métis people of northwest Saskatchewan this shift significantly influences provincial environmental governance, which affects the agency of Métis people to participate in natural resource management and decision-making in the region. To examine the agency and power of Métis communities in provincial natural resource management and decision-making, qualitative methods and a comparative case study of three Métis communities were used to analyze and interpret the social spaces that Métis people occupy in provincial environmental governance. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Community Investment in the Pandemic: Trends and Opportunities

Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities Jonathan Huntington, Vice President Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations, Cameco January 6, 2021 A Cameco Safety Moment Recommended for the beginning of any meeting Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 2 Community investment in the pandemic: Trends • Demand - increase in requests • $1 million Cameco COVID Relief Fund: 581 applications, $17.5 million in requests • Immense competition for funding dollars • We supported 67 community projects across 40 different communities in SK Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 3 Successful applicants for Cameco COVID Relief Fund Organization Community Organization Community Children North Family Resource Center La Ronge The Generation Love Project Saskatoon Prince Albert Child Care Co-operative Association Prince Albert Lakeview Extended School Day Program Inc. Saskatoon Central Urban Metis Federation Inc. Saskatoon Delisle Elementary School -Hampers Delisle TLC Daycare Inc. Birch Hills English River First Nation English River Beauval Group Home (Shirley's Place) Beauval NorthSask Special Needs La Ronge Nipawin Daycare Cooperative Nipawin Leask Community School Leask Battlefords Interval House North Battleford Metis Central Western Region II Prince Albert Beauval Emergency Operations - Incident Command Beauval Global Gathering Place Saskatoon Northern Hamlet of Patuanak Patuanak Saskatoon YMCA Saskatoon Northern Settlement of Uranium City Uranium City -

Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects

TSX: CCO website: cameco.com NYSE: CCJ currency: Cdn (unless noted) 2121 – 11th Street West, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7M 1J3 Canada Tel: 306-956-6200 Fax: 306-956-6201 Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, April 30, 2020 . Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) is pleased to announce that the company is supporting 67 community projects in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan through its $1 million Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund. “There are so many communities and charitable groups hit hard by this pandemic, yet their services are needed now more than ever,” said Cameco president and CEO Tim Gitzel. “We are extremely happy to be able to help 67 of these organizations continue to do the vital work they do every day to keep people safe and supported through this unprecedented time.” Approved projects come from 40 Saskatchewan communities from Saskatoon to the province’s far north. A full listing can be found at the end of this release. Included in the support Cameco is providing are significant numbers of personal protective equipment (PPE) for northern Saskatchewan communities and First Nations – 10,000 masks, 7,000 pairs of gloves and 7,000 litres of hand sanitizer. Donations of supplies and money from nearly 100 Cameco employees augmented the company’s initial $1 million contribution. Cameco will move quickly to begin delivering this support to the successful applicants. “I’m proud of Cameco’s employees for stepping up yet again to support the communities where they live,” Gitzel said. “It happens every time we put out a call for help, a call for volunteers, a call to assist with any of our giving campaigns, and I can’t say enough about their generosity.” Announced on April 15, the Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund was open to applications from charities, not-for-profit organizations, town offices and First Nation band offices in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan that have been impacted by the pandemic. -

Bringing Technologies to Rural and Remote Communities

Bringing Technologies to Rural and Remote Communities DR. VERONICA MCKINNEY DIRECTOR, NORTHERN MEDICAL SERVICES U OF S HIGHLIGHTS IN MEDICINE 2018 6/28/2018 Speaker Disclosure I do not have an affiliation (financial or otherwise) with a pharmaceutical, medical device or communications organization I do not intend to make therapeutic recommendations for medications that have not received regulatory approval (i.e. “off-label” use of medication). 6/28/2018 Presentation Disclosure No financial or in-kind support was received from a commercial organization to develop this presentation. The speaker has not received any payment, funding or in- kind support from a commercial organization to present at this event. 6/28/2018 Learning Objectives Will be able to name 2 challenges to providing care in remote communities. Will be able to name 2 innovative technologies that can enable patient care from a distance. Will be able to name 2 advantages to using technology 6/28/2018 Introduction Saskatchewan – many rural and remote communities Some of the largest challenges exist in the Northern parts of our province/country Often are the homes of our First Nations, Inuit and Métis Reduced access to care E.g. Morbidity and mortality rates in women and children that rival those in third world countries 6/28/2018 Northern Medical Services Division within Dept. Academic Family Medicine, U of S Mandates: Primary Medical Care and Health Promotion Consultant Medical Care Public Health/Medical Health Officer Research Education Provide physician services to Northern half of the province (Northern SHA, Athabasca Health Authority) 6/28/2018 40,000 people -50% live on reserve 307,000 km2 >85 % Indigenous (FN, Metis) -65% First Nations >65% speak a language other than English as first language -Cree -Dene -Le Michief 6/28/2018 50% our population < 25 yoa Fewer Elderly Higher dependency ratio 8 Double the birth rate compared to general population 6/28/2018 Labour and Delivery More women are voting with their feet and staying in the community to deliver. -

Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority

Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority 2015- 16 Annual Report Cover photo “Bear Approaching” Green Lake This report is available in electronic format (PDF) online at www.kyrha.ca Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority Box 40, Buffalo Narrows, Saskatchewan S0M 0J0 Toll Free 1-866-274-8506 • Local (306) 235-2220 • Fax (306) 235-4604 www.kyrha.ca 2 Keewatin Yatthé Regional Health Authority 2015 - 16 Annual Report Wholistic Health of Keewatin Yatthé Health Region Residents 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal .............................................. 5 Healthy People, Healthy Communities ...................8 Introduction ........................................................... 6 Provincial Health Regions Map ..............................9 Population by Age Group ......................................11 Alignment with Strategic Direction Population Pyramid ..............................................11 Alignment ............................................................... 8 Occupied Private Dwelling Characteristics ...........11 Strategic Direction and Goals ................................ 9 Patient Safety Occurrences ..................................15 Factors ................................................................. 11 KYRHA Facilities Map ..........................................17 KYRHA Home-Care Coverage Map .....................19 KYRHA Overview Service Utilization .................................................30 Organizational Changes ...................................... 14 Patient Safety .......................................................15 -

Business Directory Listings Prepared May 14/2021

Business Directory Listings Prepared May 14/2021 A & A Logging Amachewespemawin Co-operative Assoc. Ltd. Box 157 Box 250 Green Lake, SK Stanley Mission, SK S0M 1B0 S0J 2P0 Location: Green Lake Location: Stanley Mission Contact: Art Laliberte Contact: Eva McKenzie, Acting Manager Tel: 306-832-2100 Tel: 306-635-2020 Fax: 306-832-2100 Fax: 306-635-2070 Description: Stump to dump & log hauling. Email: [email protected] Description: Retail store, Gas Bar, & Groceries. A & L Transport Box 155 Amachewespimawin Co-operative Restaurant Stony Rapids, SK Box 250 S0J 2R0 Stanley Mission, SK Location: Stony Rapids S0J 2P0 Contact: Morris Gabrush, Owner Location: Stanley Mission Tel: 306-439-2157 Contact: Pam McLeod, Manager Fax: 306-439-4992 Tel: 306-635-2093 Email: [email protected] Fax: 306-635-2070 Description: Trucking, Storage, Light Truck Rental Description: Chester Fried Chicken, fast food Units, Construction Equipment: Dozer, restaurant. Loader, Motor Grader, Rick Truck, Fuel Truck, Water Truck, Tractor/Skidder and Gravel Screener Amys Bar & Grill Motel Beauval, SK S0M 0G0 Aboriginal Headstart Location: Beauval Box 269 Contact: Mitch Beauval, SK Tel: 306-288-4700 S0M 0G0 Description: 7 room motel (satellite), Tavern & Off Location: Beauval Sale. Contact: Patty Gauthier Tel: 306-288-2274 Fax: 306-288-4502 Andys Store Email: [email protected] Box 58 Description: School for 3 & 4 year olds & parental Southend, SK support. S0J 2L0 Location: Southend Contact: Andy Park Als Place Motel Tel: 306-758-0001 Box 126 Fax: 306-758-0002 Stony Rapids, SK Description: Gas, diesel, grocery, confectionery, & S0J 2R0 ATM. Location: Stony Rapids Contact: Al Sayn Tel: 306-439-2057 Fax: 306-439-2047 Email: [email protected] Website: www.alsplace.ca Description: Deluxe guest rooms,restaurant. -

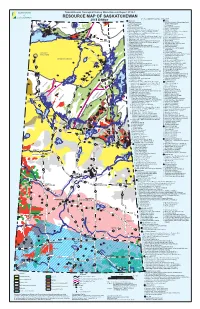

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14. -

About ENGLISH RIVER FIRST NATION

ENGLISH RIVER FIRST NATION About ENGLISH RIVER FIRST NATION The English River First Nation (ERFN) is comprised of seven different Reserves including: Cree Lake, Porter Island, Elak Dase, Knee Lake, Dipper Rapids, Wapachewunak, and LaPlonge. The home reserve is located in Patuanak, near the Churchill River. The river provides transportation and allows for fishing, hunting and gathering. It also provides economic opportunities for outfitting and tourism. English River First Nation is a Dene speaking community. HIGHLIGHTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ECONOMICS • On August 28, 1906, Chief William Apesis signed Treaty 10 on IN SASKATOON REGION behalf of English River First Nation. Land Holdings (Total) 135 acres • ERFN has a vibrant economy with many people owning their Rural Reserve (RM of Corman Park) 135 acres own businesses or being employed through the First Nation. Status: Partially developed. Further development options are • Des Nedhe Development, ERFN’s economic development being considered. entity, continues to create financial and economic Employment (On Reserve) opportunities for their members. Full Time, Part-Time, Seasonal Employee 535 • Tron Construction & Mining, which is owned and operated by Business Developments - Current Tron Construction & Mining ERFN, provides general contracting services for construction projects and maintenance contracts, as well as heavy earth Grasswood Travel and Business Centre Des Nedhe Development LP moving, electrical, mechanical, pipeline and environmental Grasswood Petro Canada cleanup for the mining sector. English River Property Management • ERFN also operates Grasswood Travel and Business Centre Minetec Mining Supply Company located just south of Saskatoon, which includes 80,000 square Mudjatik Thyssen Mining feet of office space, a gas bar and convenience store, two Business Developments - Proposed commercial strip malls, and other warehousing buildings. -

12Th Annual Report for the Period April 1St, 2013 to March 31St, 2014 Compiled by Michael Fulton, Educon Services Inc

KidsFirst NORTH Staff at August 2013 Retreat in Saskatoon 12th Annual Report For the period April 1st, 2013 to March 31st, 2014 Compiled by Michael Fulton, Educon Services Inc. Table of Contents Program Manager’s Foreword 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction and Background Information 6 Vision, Model Description and Guiding Principles Organization Chart and Personnel Goals and Accomplishments Challenges Health Regions, Communities Served and Population Home Visiting Supervision, Home Visitor and Program Support Summaries Agency Contracts and Services Significant Program Enhancements in 2013-14 Prenatal Families and Screening and Assessment Data Regional Reports 18 MCRRHA-Creighton/Denare Beach, Sandy Bay, La Ronge, Air Ronge and Pinehouse KYRHA-Buffalo Narrows, La Loche, Beauval, Green Lake and Ile-a-la-Crosse KTRHA-Cumberland House AHA-The Far North including Stony Rapids Community Development Report 27 Mental Health Reports 35 MCRRHA Region-Penny Frazer KYRHA Region-Dawnali Reimer Professional Development and Staff Training Report 40 Good News Stories from the Regions 49 Parenting and Family Supports Early Childhood Development and Learning Mental Health and Healthy Lifestyles Community Supports Program Manager’s Concluding Remarks 75 KidsFirst NORTH Addresses and Contact Information 76 2 Program Manager’s Foreword KidsFirst NORTH celebrates its 12th birthday this year. Looking back on the work we have done this past year we see that our focus on relationships, strengthening parents and family units and developing our program in our beautiful Northern Communities have been central to our work to growing great children and families. We are proud to serve the families in Northern Saskatchewan and love helping our families to be safe, secure, happy and healthy.