Pinehouse-Dipper Integrated Forest Land Use Plan Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

True North // September 2017

True North // September 2017 cameco in northern saskatchewan Cameco partners with the Red Cross to support Pelican Narrows evacuees (p.2) WINTER Surviving off 2015 Land and Water Fond du Lac Canoe Quest is a Success Far From Home Red Cross and Cameco employees delivered baby strollers to young families from northeastern Saskatchewan while they were evacuated to Prince Albert and Saskatoon during the wildfires earlier this fall. “Once again, Cameco came through to help those Cameco proud to evacuated in northern Saskatchewan,” said Cindy support evacuees Fuchs, Vice-President of the Canadian Red Cross in during fires Saskatchewan. “We are so thankful for Cameco’s support – it makes a world of difference for people forced from their homes.” Wildfires forced more than 2,700 people from the Cree communities of Pelican Narrows and Sandy Bay in late August. The evacuation ban was lifted September 13. During that time evacuees stayed in Prince Albert and Saskatoon with the aid of the Red Cross. Cameco was proud to partner with the organization and provided baby strollers, movie passes and food to make the stay more comfortable. Cameco also contributed $25,000 to the Red Cross’s Red Gala. Proceeds from the gala help support disaster relief. source: Government of Saskatchewan Facebook page page 2 True North // September 2017 Fond du Lac Youth Canoe Quest imparts important traditional skills The participants in the Fond du Lac also visited the basecamp to perform, Toutsaint says the experience made Canoe Quest met with stunning as well as other members who wanted such an impression that the community sunrises for five days at the beginning to cheer the group along. -

Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: a Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan

University of Alberta Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: A Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan by Bryn Alan Politylo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Rural Sociology Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Bryn Alan Politylo Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Recently northwest Saskatchewan has seen a rapid push towards large-scale development corresponding with a shifting political economy in the province. For the rights- bearing Métis people of northwest Saskatchewan this shift significantly influences provincial environmental governance, which affects the agency of Métis people to participate in natural resource management and decision-making in the region. To examine the agency and power of Métis communities in provincial natural resource management and decision-making, qualitative methods and a comparative case study of three Métis communities were used to analyze and interpret the social spaces that Métis people occupy in provincial environmental governance. -

Canoeingthe Clearwater River

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | The clearwater river To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 1-2 weeks canoeing the clearwater river 105 km History of the Clearwater River For years fur traders from the east tried in vain to find a route to Athabasca country. Things changed in 1778, when Peter Pond crossed The legendary Clearwater has it the 20 km Methye Portage from the headwaters of the east-flowing all—unspoiled wilderness, thrilling Churchill River to the eventual west-bound Clearwater River. Here whitewater, unparalleled scenery was the sought-after land bridge between the Hudson Bay and and inviting campsites with Arctic watersheds, opening up the vast Canadian north. Paddling the fishing outside the tent door. This Clearwater today, you not only follow in the wake of voyageurs with Canadian Heritage River didn’t their fur-laden birchbark canoes, but also a who’s who of northern merely play a role in history; it exploration, the likes of Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson, changed its very course. John Franklin and Peter Pond. Saskatoon Saskatoon Regina Regina • Canoeing Route • Vehicle Highway Broach Lake Patterson Lake n Forrest Lake Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 955 A T ALBER Fort McMurray Clearwater River Broach Lake Provincial Park Careen Lake Clearwater River Patterson Lake n Gordon Lake Forrest Lake La Loche Lac La Loche Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 155 Churchill Lake Peter Pond 955 Lake A SASKATCHEWAN Buffalo Narrows T ALBER Skull Canyon, Clearwater River Provincial Park. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Northern Recreation Grants Regulations

1 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS D-11.1 REG 3 The Northern Recreation Grants Regulations Repealed by Saskatchewan Regulations 27/97 (effective April 23, 1997). Formerly Chapter D-11.1 Reg 3* (effective June 8, 1983) as amended by Saskatchewan Regulations 92/83. *Note: The chapter number of this regulation originated in the now repealed Department of Culture and Recreation Act. NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 D-11.1 REG 3 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS Table of Contents 1 Title 2 Interpretation 3 Community program support grant 4 Recreation worker support grant 5 Regional grants 6 Special projects and leadership development 3 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS D-11.1 REG 3 CHAPTER D-11.1 REG 3 The Renewable Resources, Recreation and Culture Act Title 1 These regulations may be cited as The Northern Recreation Grants Regulations. Interpretation 2 In these regulations: (a) “council” means the elected council or governing body of a municipality; (b) “fiscal year” means the fiscal year of the Government of Saskatchewan in respect of which a grant is paid in accordance with these regulations; (c) “joint recreation board” means the recreation board established by a minimum of two municipalities which occupy adjacent geographic -

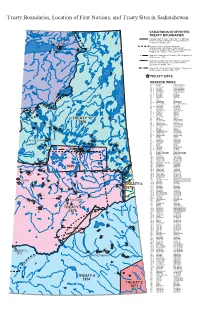

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Community Investment in the Pandemic: Trends and Opportunities

Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities Jonathan Huntington, Vice President Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations, Cameco January 6, 2021 A Cameco Safety Moment Recommended for the beginning of any meeting Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 2 Community investment in the pandemic: Trends • Demand - increase in requests • $1 million Cameco COVID Relief Fund: 581 applications, $17.5 million in requests • Immense competition for funding dollars • We supported 67 community projects across 40 different communities in SK Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 3 Successful applicants for Cameco COVID Relief Fund Organization Community Organization Community Children North Family Resource Center La Ronge The Generation Love Project Saskatoon Prince Albert Child Care Co-operative Association Prince Albert Lakeview Extended School Day Program Inc. Saskatoon Central Urban Metis Federation Inc. Saskatoon Delisle Elementary School -Hampers Delisle TLC Daycare Inc. Birch Hills English River First Nation English River Beauval Group Home (Shirley's Place) Beauval NorthSask Special Needs La Ronge Nipawin Daycare Cooperative Nipawin Leask Community School Leask Battlefords Interval House North Battleford Metis Central Western Region II Prince Albert Beauval Emergency Operations - Incident Command Beauval Global Gathering Place Saskatoon Northern Hamlet of Patuanak Patuanak Saskatoon YMCA Saskatoon Northern Settlement of Uranium City Uranium City -

Stanley Mission Saskatchewan Interview

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: MURDOCH CHARLES INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: STANLEY MISSION SASKATCHEWAN INTERVIEW LOCATION: STANLEY MISSION SASKATCHEWAN TRIBE/NATION: METIS LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DATE OF INTERVIEW: SEPTEMBER 14, 1976 INTERVIEWER: MURRAY DOBBIN INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: JOANNE GREENWOOD SOURCE: SASK. SOUND ARCHIVES PROGRAMME TAPE NUMBER: IH-357 DISK: TRANSCRIPT DISC 73 PAGES: 16 RESTRICTIONS: NONE MURDOCH CHARLES: Murdoch Charles is a trapper and prospector from Stanley Mission. He worked with Jim Brady for a short time. HIGHLIGHTS: - Jim Brady as a friend. - From his experience in the bush discusses Brady's disappearance. GENERAL COMMENTS: Murdoch Charles is a resident of Stanley and knew Jim slightly. Tells a few details of the mining operation at Nistowiak falls. Talks a bit about what a bushman would do if he was lost. INTERVIEW: Murray: I'm speaking to Murdoch Charles of Stanley Mission who was a friend of Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris. Murdoch, you worked with Jim when he was prospecting, is that right? Murdoch: That's right. One winter I went with him, went down the Churchill River close to Hudson Bay there. We were staking claims. That's after New Years. It was cold at that time. Murray: What year would that have been, do you remember? Murdoch: Gee, I couldn't remember. It was quite a ways. Murray: Sixties or fifties? Murdoch: Yeah, like that. Murray: Late 1950s maybe? Murdoch: Yeah. Murray: Could you describe Jim? What kind of man was he? How would you describe him? Murdoch: Well, the way he treated me, you know, he was a good man. And he never complained anything what we're doing. -

Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects

TSX: CCO website: cameco.com NYSE: CCJ currency: Cdn (unless noted) 2121 – 11th Street West, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7M 1J3 Canada Tel: 306-956-6200 Fax: 306-956-6201 Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund Supports 67 Community Projects Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, April 30, 2020 . Cameco (TSX: CCO; NYSE: CCJ) is pleased to announce that the company is supporting 67 community projects in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan through its $1 million Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund. “There are so many communities and charitable groups hit hard by this pandemic, yet their services are needed now more than ever,” said Cameco president and CEO Tim Gitzel. “We are extremely happy to be able to help 67 of these organizations continue to do the vital work they do every day to keep people safe and supported through this unprecedented time.” Approved projects come from 40 Saskatchewan communities from Saskatoon to the province’s far north. A full listing can be found at the end of this release. Included in the support Cameco is providing are significant numbers of personal protective equipment (PPE) for northern Saskatchewan communities and First Nations – 10,000 masks, 7,000 pairs of gloves and 7,000 litres of hand sanitizer. Donations of supplies and money from nearly 100 Cameco employees augmented the company’s initial $1 million contribution. Cameco will move quickly to begin delivering this support to the successful applicants. “I’m proud of Cameco’s employees for stepping up yet again to support the communities where they live,” Gitzel said. “It happens every time we put out a call for help, a call for volunteers, a call to assist with any of our giving campaigns, and I can’t say enough about their generosity.” Announced on April 15, the Cameco COVID-19 Relief Fund was open to applications from charities, not-for-profit organizations, town offices and First Nation band offices in Saskatoon and northern Saskatchewan that have been impacted by the pandemic. -

Bringing Technologies to Rural and Remote Communities

Bringing Technologies to Rural and Remote Communities DR. VERONICA MCKINNEY DIRECTOR, NORTHERN MEDICAL SERVICES U OF S HIGHLIGHTS IN MEDICINE 2018 6/28/2018 Speaker Disclosure I do not have an affiliation (financial or otherwise) with a pharmaceutical, medical device or communications organization I do not intend to make therapeutic recommendations for medications that have not received regulatory approval (i.e. “off-label” use of medication). 6/28/2018 Presentation Disclosure No financial or in-kind support was received from a commercial organization to develop this presentation. The speaker has not received any payment, funding or in- kind support from a commercial organization to present at this event. 6/28/2018 Learning Objectives Will be able to name 2 challenges to providing care in remote communities. Will be able to name 2 innovative technologies that can enable patient care from a distance. Will be able to name 2 advantages to using technology 6/28/2018 Introduction Saskatchewan – many rural and remote communities Some of the largest challenges exist in the Northern parts of our province/country Often are the homes of our First Nations, Inuit and Métis Reduced access to care E.g. Morbidity and mortality rates in women and children that rival those in third world countries 6/28/2018 Northern Medical Services Division within Dept. Academic Family Medicine, U of S Mandates: Primary Medical Care and Health Promotion Consultant Medical Care Public Health/Medical Health Officer Research Education Provide physician services to Northern half of the province (Northern SHA, Athabasca Health Authority) 6/28/2018 40,000 people -50% live on reserve 307,000 km2 >85 % Indigenous (FN, Metis) -65% First Nations >65% speak a language other than English as first language -Cree -Dene -Le Michief 6/28/2018 50% our population < 25 yoa Fewer Elderly Higher dependency ratio 8 Double the birth rate compared to general population 6/28/2018 Labour and Delivery More women are voting with their feet and staying in the community to deliver. -

From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Érudit Article "From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects" David M. Quiring Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 17, n° 1, 2006, p. 151-178. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/016106ar DOI: 10.7202/016106ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 10:21 From the Bush to the Village in Northern Saskatchewan: Contrasting CCF Community Development Projects DAVID M. QUIRING Abstract The election of the CCF in 1944 brought rapid change for the residents of northern Saskatchewan. CCF initiatives included encouraging northern aboriginals to trade their semi-nomadic lifestyles for lives in urban settings. The establishment of Kinoosao on Reindeer Lake provides an example of how CCF planners established new villages; community development processes excluded local people.