Leah Dorion-Paquin Side a 0.0 Leah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uranium City, Black Lake, Camsell Portage, Fond Du Lac, Stony Rapids, and Wollaston/Hatchet Lake

CanNorth 2015 AthabascaUranium Working City Group Environmental Monitoring Program ABOUT THE AWG PROGRAM The Athabasca Working Group (AWG) environmental monitoring program began in the Athabasca region of northern Saskatchewan in 2000. The program provides residents with opportunities to test the environment around their communities for parameters that could come from uranium mining and milling operations. These parameters can potentially be spread by water flowing from lakes near the uranium operations, and small amounts may also be spread through the air. In order to address local residents’ concerns, lakes, rivers, plants, wildlife, and air quality are tested each yeah near the northern communities of Uranium City, Black Lake, Camsell Portage, Fond du Lac, Stony Rapids, and Wollaston/Hatchet Lake. The types of plants and animals selected, the locations chosen for sampling, and the sample collections were carried out by, or with the help of, northern community members. The purpose of this brochure is to inform the public of the 2015 environmental monitoring program results in the Uranium City area. STUDY AREA Water, sediment, and fish were sampled from a reference site and a potential exposure site in the Uranium City area in 2015. Fredette Lake was chosen as the reference site because it is not influenced by uranium operations. Black Bay of Lake Athabasca (Black Bay) is referred to as the potential exposure site because it is located downstream of the active uranium operations in northern Saskatchewan. Air quality is monitored at two locations near the community of Uranium City and plant and wildlife samples are collected each year near the community when available. -

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description

Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Denison Mines Corp. May 2019 WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Wheeler River Project Provincial Technical Proposal and Federal Project Description Project Summary English – Page ii French – Page x Dene – Page xx Cree – Page xxviii PAGE i WHEELER RIVER PROJECT TECHNICAL PROPOSAL & PROJECT DESCRIPTION Summary Wheeler River Project The Wheeler River Project (Wheeler or the Project) is a proposed uranium mine and processing plant in northern Saskatchewan, Canada. It is located in a relatively undisturbed area of the boreal forest about 4 km off of Highway 914 and approximately 35 km north-northeast of the Key Lake uranium operation. Wheeler is a joint venture project owned by Denison Mines Corp. (Denison) and JCU (Canada) Exploration Company Ltd. (JCU). Denison owns 90% of Wheeler and is the operator, while JCU owns 10%. Denison is a uranium exploration and development company with interests focused in the Athabasca Basin region of northern Saskatchewan, Canada with a head office in Toronto, Ontario and technical office in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Historically Denison has had over 50 years of uranium mining experience in Saskatchewan, Elliot Lake, Ontario, and in the United States. Today, the company is part owner (22.5%) of the McClean Lake Joint Venture which includes the operating McClean Lake uranium mill in northern Saskatchewan. To advance the Project, Denison is applying an innovative approach to uranium mining in Canada called in situ recovery (ISR). The use of ISR mining at Wheeler means that there will be no need for a large open pit mining operation or multiple shafts to access underground mine workings; no workers will be underground as the ISR process is conducted from surface facilities. -

True North // September 2017

True North // September 2017 cameco in northern saskatchewan Cameco partners with the Red Cross to support Pelican Narrows evacuees (p.2) WINTER Surviving off 2015 Land and Water Fond du Lac Canoe Quest is a Success Far From Home Red Cross and Cameco employees delivered baby strollers to young families from northeastern Saskatchewan while they were evacuated to Prince Albert and Saskatoon during the wildfires earlier this fall. “Once again, Cameco came through to help those Cameco proud to evacuated in northern Saskatchewan,” said Cindy support evacuees Fuchs, Vice-President of the Canadian Red Cross in during fires Saskatchewan. “We are so thankful for Cameco’s support – it makes a world of difference for people forced from their homes.” Wildfires forced more than 2,700 people from the Cree communities of Pelican Narrows and Sandy Bay in late August. The evacuation ban was lifted September 13. During that time evacuees stayed in Prince Albert and Saskatoon with the aid of the Red Cross. Cameco was proud to partner with the organization and provided baby strollers, movie passes and food to make the stay more comfortable. Cameco also contributed $25,000 to the Red Cross’s Red Gala. Proceeds from the gala help support disaster relief. source: Government of Saskatchewan Facebook page page 2 True North // September 2017 Fond du Lac Youth Canoe Quest imparts important traditional skills The participants in the Fond du Lac also visited the basecamp to perform, Toutsaint says the experience made Canoe Quest met with stunning as well as other members who wanted such an impression that the community sunrises for five days at the beginning to cheer the group along. -

Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: a Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan

University of Alberta Politics, Power, and Environmental Governance: A Comparative Case Study of Three Métis Communities in Northwest Saskatchewan by Bryn Alan Politylo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Rural Sociology Department of Resource Economics and Environmental Sociology ©Bryn Alan Politylo Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Recently northwest Saskatchewan has seen a rapid push towards large-scale development corresponding with a shifting political economy in the province. For the rights- bearing Métis people of northwest Saskatchewan this shift significantly influences provincial environmental governance, which affects the agency of Métis people to participate in natural resource management and decision-making in the region. To examine the agency and power of Métis communities in provincial natural resource management and decision-making, qualitative methods and a comparative case study of three Métis communities were used to analyze and interpret the social spaces that Métis people occupy in provincial environmental governance. -

Uranium City

Community Meeting Record January 29 – Feb 1, 2019 Uranium City – January 29, 2019 Attendees • Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) o Ian Wilson o David Sanscartier o Chris Reid o Robyn Morris o John Sprague o Jennifer Brown • Mina Patel (Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC)) • Jaynine McCrea (Fond du Lac Nuna Joint Venture (FDLNJV)) • Dean Classen (Uranium City Contracting (UCC)) • Kyle Remus (QMPoints) • Glen Strong (QMPoints) • Emily Jones (Translator) Agenda 1. Prayer 2. Lunch 3. Video 4. Satellite Sites (David) 5. Uranium City Contracting (Dean) 6. Gunnar Overview (Chris) 7. Gunnar Other Site Aspects (Chris) 8. Gunnar Other Site Aspects (QMPoints) 9. Gunnar Tailings (Robyn) 10. Gunnar Tailings (Jaynine) 11. Lorado (Ian) 12. Photo Contest (John) 13. CNSC (Mina) 14. Prize Draws and Close Discussion Satellite Sites Q. Looking at the criteria you have for workers on the project, do you have criteria for a certain number of or percentage of women? A. There is nothing specific, but the wording states that the process is to be all inclusive and non- discriminatory. Q. What about the criteria for equipment usage? Is that including Indigenous? A. It is not specific to Indigenous. The second point is for the equipment, not the operator. 1 Community Meeting Record January 29 – Feb 1, 2019 Q. How is the gamma survey done? Is it on contact? A. The survey is done one meter above the ground. Q. How much soil is required to cover the gamma spots? What is required for protection? A. We are putting 30-50 cm over the hot spots, which is more than enough. -

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT AID 539 Mining and Access Roads

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT AID 539 Mining and Access Roads.—In 1951 the Department of Mines undertook a program of road construction in the mineralized areas of the province, to open them for prospecting and development and to facilitate the actual operation of mining enterprises. When the importance of this program in its relation to the whole development of northern Ontario became apparent, the Government decided that its scope should be widened and, with that end in view, an interdepartmental committee was set up early in 1955 to decide on matters of policy and to determine the locations and priorities of the proposed roads. The Minister of Mines sits on this committee with the Ministers of Lands and Forests, of Treasury, of Highways and of Reform Institutions. The Department of Highways supervises the construction of all access roads. Certain roads may be subsidized while others may be financed solely by Department of Mines funds. The sum of $1,500,000 a year has been made available for such projects. Manitoba.—The Mines Branch of the Manitoba Department of Mines and Natural Resources offers five main services of assistance to the mining industry: maintenance, by the Mining Recorder's offices at Winnipeg and The Pas, of all records essential to the granting and retention of titles to every mineral location in Manitoba; compilation, by the geological staff of the Branch, of historical and current information pertinent to mineral occurrences of interest and expansion of this information by a continuing program of geological mapping; enforcement of mine safety regulations and, by collaboration with industry, introduction of new practices such as those concerned with mine ventilation and the training of mine rescue crews which contribute to the health and welfare of mine workers; and maintenance of a chemical and assay laboratory to assist the prospector and the professional man in the classification of rocks and minerals and the evaluation of mineral occurrences. -

1675 Uranium City Final.Indd

AAWGWG 22013013 UUraniumranium CityCity AAthabascathabasca WorkingWorking GroupGroup CanNorth EEnvironmentalnvironmental MonitoringMonitoring ProgramProgram ABOUT THE AWG PROGRAM TheThe AthabascaAthabasca WorWorkingking GGrouproup (A(AWG)WG) eenvironmentalnvironmental monmonitoringitoring program bbeganegan iinn tthehe year 2000 andand pprovidesrovides rresidentsesidents wwithith oopportunitiespportunities to test tthehe enenvironmentvironment aaroundround ttheirheir comcommunitiesmunities forfor parametersparameters ththatat ccouldould ccomeome ffromrom uuraniumranium mminingining aandnd mmillingilling operatiooperations.ns. TheThesese pparametersarameters can potentiallypotentially bbee sspreadpread by watwaterer fflowinglowing ffromrom llakesakes nnearear tthehe uraniuuraniumm ooperations,perations, anandd ssmallmall amountsamounts maymay aalsolso bebe spreadspread tthroughhrough tthehe aiair.r. IInn oorderrder ttoo aaddressddress llocalocal rresidents’esidents’ coconcerns,ncerns, llakes,akes, rivers,rivers, pplants,lants, wwildlife,ildlife, aandnd aairir quaqualitylity aarere ttestedested nnearear tthehe nnorthernorthern ccommunitiesommunities ooff Uranium City, BlackBlack Lake,Lake, CamsellCamsell Portage,Portage, FFond-du-Lac,ond-du-Lac, SStonytony RaRapids,pids, aandnd WWollastonollaston LaLake/Hatchetke/Hatchet LaLake.ke. TheThe ttypesypes ooff plantsplants and anianimalsmals sselected,elected, tthehe llocationsocations chchosenosen fforor samsampling,pling, aandnd tthehe sasamplemple collectionscollections werewere carriedcarried -

Canoeingthe Clearwater River

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | The clearwater river To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 1-2 weeks canoeing the clearwater river 105 km History of the Clearwater River For years fur traders from the east tried in vain to find a route to Athabasca country. Things changed in 1778, when Peter Pond crossed The legendary Clearwater has it the 20 km Methye Portage from the headwaters of the east-flowing all—unspoiled wilderness, thrilling Churchill River to the eventual west-bound Clearwater River. Here whitewater, unparalleled scenery was the sought-after land bridge between the Hudson Bay and and inviting campsites with Arctic watersheds, opening up the vast Canadian north. Paddling the fishing outside the tent door. This Clearwater today, you not only follow in the wake of voyageurs with Canadian Heritage River didn’t their fur-laden birchbark canoes, but also a who’s who of northern merely play a role in history; it exploration, the likes of Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson, changed its very course. John Franklin and Peter Pond. Saskatoon Saskatoon Regina Regina • Canoeing Route • Vehicle Highway Broach Lake Patterson Lake n Forrest Lake Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 955 A T ALBER Fort McMurray Clearwater River Broach Lake Provincial Park Careen Lake Clearwater River Patterson Lake n Gordon Lake Forrest Lake La Loche Lac La Loche Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 155 Churchill Lake Peter Pond 955 Lake A SASKATCHEWAN Buffalo Narrows T ALBER Skull Canyon, Clearwater River Provincial Park. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Northern Recreation Grants Regulations

1 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS D-11.1 REG 3 The Northern Recreation Grants Regulations Repealed by Saskatchewan Regulations 27/97 (effective April 23, 1997). Formerly Chapter D-11.1 Reg 3* (effective June 8, 1983) as amended by Saskatchewan Regulations 92/83. *Note: The chapter number of this regulation originated in the now repealed Department of Culture and Recreation Act. NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 D-11.1 REG 3 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS Table of Contents 1 Title 2 Interpretation 3 Community program support grant 4 Recreation worker support grant 5 Regional grants 6 Special projects and leadership development 3 NORTHERN RECREATION GRANTS D-11.1 REG 3 CHAPTER D-11.1 REG 3 The Renewable Resources, Recreation and Culture Act Title 1 These regulations may be cited as The Northern Recreation Grants Regulations. Interpretation 2 In these regulations: (a) “council” means the elected council or governing body of a municipality; (b) “fiscal year” means the fiscal year of the Government of Saskatchewan in respect of which a grant is paid in accordance with these regulations; (c) “joint recreation board” means the recreation board established by a minimum of two municipalities which occupy adjacent geographic -

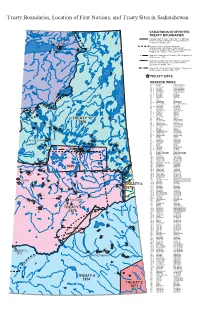

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Community Investment in the Pandemic: Trends and Opportunities

Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities Jonathan Huntington, Vice President Sustainability and Stakeholder Relations, Cameco January 6, 2021 A Cameco Safety Moment Recommended for the beginning of any meeting Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 2 Community investment in the pandemic: Trends • Demand - increase in requests • $1 million Cameco COVID Relief Fund: 581 applications, $17.5 million in requests • Immense competition for funding dollars • We supported 67 community projects across 40 different communities in SK Community investment in the pandemic: trends and opportunities (January 6, 2021) 3 Successful applicants for Cameco COVID Relief Fund Organization Community Organization Community Children North Family Resource Center La Ronge The Generation Love Project Saskatoon Prince Albert Child Care Co-operative Association Prince Albert Lakeview Extended School Day Program Inc. Saskatoon Central Urban Metis Federation Inc. Saskatoon Delisle Elementary School -Hampers Delisle TLC Daycare Inc. Birch Hills English River First Nation English River Beauval Group Home (Shirley's Place) Beauval NorthSask Special Needs La Ronge Nipawin Daycare Cooperative Nipawin Leask Community School Leask Battlefords Interval House North Battleford Metis Central Western Region II Prince Albert Beauval Emergency Operations - Incident Command Beauval Global Gathering Place Saskatoon Northern Hamlet of Patuanak Patuanak Saskatoon YMCA Saskatoon Northern Settlement of Uranium City Uranium City