Pictographs in Northern Saskatchewan: Vision Quest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

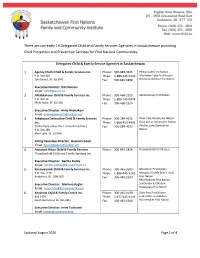

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Denison Mines Corp. Wheeler River Project Denison Mines Corp. Projet

UNPROTECTED/NON PROTÉGÉ ORIGINAL/ORIGINAL CMD: 19-H111 Date signed/Signé le : NOVEMBER 29, 2019 Request for a Commission Decision on Demande de décision de la the Scope of an Environmental Commission sur la portée d’une Assessment for évaluation environnementale pour ce qui suit Denison Mines Corp. Denison Mines Corp. Wheeler River Project Projet Wheeler River Hearing in writing based solely on Audience fondée uniquement sur des written submissions mémoires Scheduled for: Prévue pour : December 2019 Décembre 2019 Submitted by: Soumise par : CNSC Staff Le personnel de la CCSN e-Doc: 6005470 (WORD) e-Doc: 6016260 (PDF) 19-H111 UNPROTECTED/ NON PROTÉGÉ Summary Résumé This Commission member document Le présent document à l’intention des (CMD) pertains to a request for a decision commissaires (CMD) concerne une regarding: demande de décision au sujet de : . the scope of the factors to be taken into . la portée des éléments à prendre en account in the environmental compte dans l’évaluation assessment being conducted for the environnementale pour le projet Wheeler River Project Wheeler River The following actions are requested of the La Commission pourrait considérer prendre Commission: les mesures suivantes : . Determine the scope of the factors of . Déterminer la portée des éléments de the environmental assessment. l’évaluation environnementale. The following items are attached: Les pièces suivantes sont jointes : . regulatory basis for the . fondement réglementaire des recommendations recommandations . environmental assessment process map . diagramme du processus d’évaluation . disposition table of public and environnementale Indigenous groups’ comments on the . tableau des réponses aux commentaires project description for the Wheeler du public et des groupes autochtones River Project sur la description du projet Wheeler . -

Creighton-Flin Flon

Flin Flon Domain of Saskatchewan – Dataset Descriptions The Flin Flon domain hosts one of the most prolific Precambrian volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) districts in the world, with over 160 million tonnes of ore produced from at least 28 deposits in Saskatchewan and Manitoba since the start of the 20th century. Situated in the Reindeer Zone of the of the Trans-Hudson Orogen, rocks of this domain comprise dominantly metamorphosed and polydeformed volcanoplutonic terranes with subordinate siliciclastic sedimentary sequences. Volcanic rocks vary in composition throughout the domain and were originally emplaced in a variety of tectonic settings, including island arc(s), arc rift, ocean floor, and ocean pleateau. The VMS deposits are hosted primarily by Paleoproterozoic juvenile arc rocks in one of several defined lithotectonic assemblages. The datasets provided for this area are located within a ~12,000 km2 area of the Flin Flon Domain of Saskatchewan that contains several past producing base metal mines and a multitude of known mineral occurrences. The northern quarter of the area is underlain by exposed Precambrian Shield, whereas the southern three-quarters consists of Precambrian basement situated beneath up to 200 metres of undeformed, Phanerozoic sedimentary rocks. The sedimentary cover in this southern portion makes exploration of the Precambrian rocks particularly challenging. The datasets provided for this area consist of: (i) airborne geophysical survey data, and (ii) multiple GIS datasets from the exposed Precambrian Shield and/or the buried Precambrian basement and/or the Phanerozoic sedimentary cover. The geophysical data comprises digital data for 22 airborne surveys including industry-derived data submitted to the Saskatchewan Geological Survey through assessment work reports, and surveys funded by provincial and federal governments. -

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background Document La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Management Plan La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE# Lists of Tables and Figures................................................................................... ii Chapter 1 - The La Ronge Planning Area........................................................... 1 Chapter 2 - Ecological and Natural Resource Description............................... 4 2.1 Landscape Area Description..................................................... 4 2.1.1 Sisipuk Plain Landscape Area................................... 4 2.1.2 La Ronge Lowland Landscape Area.......................... 4 2.2 Forest Resources..................................................................... 4 2.3 Water Resources..................................................................... 5 2.4 Geology.................................................................................... 5 2.5 Wildlife Resources.................................................................... 6 2.6 Fish Resources......................................................................... 9 Chapter 3 - Existing Resource Uses and Values................................................11 3.1 Timber......................................................................................12 3.2 Non-Timber Forest Products......................................................13 -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

New Results from Mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan

Stratigraphy, Structure, and Silicification: New Results From Mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan Kate MacLachlan MacLachlan (2006): Stratigraphy, structure, and silicification: new results from mapping in the Flin Flon Mining Camp, Creighton, Saskatchewan; in Summary of Investigations Volume 2, 2006, Saskatchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Industry Resources, Misc. Rep. 2006-4.2, CD-ROM, Paper A-9, 25p. Abstract Two areas in the Flin Flon mining camp were mapped at a scale of 1:5000, one area between Douglas Lake and West Arm Road on the west limb of the Beaver Road Anticline, and the other on the peninsula between Green Lake and Phantom Lake. In the Douglas Lake area, mapping was undertaken in the hanging wall of the west-younging, felsic-dominated Myo member of the Flin Flon formation. Significant findings include, an extrusive felsic unit above the upper contact of the Myo member, abundant peperite at several stratigraphic levels, an up to 100 m wide zone of semi-conformable silicification, and pervasive sinistral shearing that post-dates the Phantom Intrusive Suite. In the Green Lake Peninsula area, three fault-bounded successions with opposing younging directions were recognized. The easternmost succession, east of the newly defined Burley Lake Fault (a modified version of the Phantom Lake Fault), is part of the west-younging Louis formation on the east limb of the Burley Lake Syncline. The east-younging succession between the Burley Lake and Green Lake faults comprises a large component of fine- grained mafic volcaniclastic rocks intercalated with aphyric and plagioclase ± pyroxene porphyritic flows, and is tentatively correlated with the Hidden formation. -

Athabasca Region

Northern Settlement of Brabant Lake Community Highlights Brabant, a community of 100 people, is located two driving hours north of La Ronge. Trapping, Athabasca tourism, and mining are the main industries of the area. This village is located in the breath- taking beauty of the Precambrian Shield.1 Boreal West Local Government Mayor and Council:2 Churchill Chairman: Rebecca Shirley Bueckert River Member: o Harriet Jean McKenzie o Peter McKenzie First Nations Presence: There are no First Nations (Reserves) in the immediate vicinity of Brabant. Nearest First Nations: o Grandmother’s Bay reserve of Lac La Ronge Indian Band (50 km) Central Tribal Council: P rince Albert Grand Council (PAGC) Demographics3 Brabant Lake North Saskatchewan Population 102 36, 557 1, 033, 381 Aboriginal population (%) 50 86% 15% Youth population, 15 to 29 Not available 9, 620 105, 240 Major Languages Cree, English Cree, Dene, English English, Michif Labour Force Participation Rate, 15+ (%) 20 50% 68% Employment Rate, 15+ (%) 10 40% 65% Unemployment Rate (%) 0 20% 6% Median family income: Not available $31,007 $58,563 Median earnings (persons 15+ years): Not available $18,449 $23,025 Population 25+ with a high school diploma (%) 0 16% 144, 475 Population 25+ with a trades, college, or 0 36% 303, 440 university certificate, diploma, or degree (%) Northern Settlement of Brabant Lake Economic Environment Key Industries – The mining industry is a large employer, with employees community and doing shifts “in and out” at the various northern mining surrounding area -

Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Lena May Seegerts Email: [email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306 845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Phone: 306 845-1427 Box 368 Fax: 306 845-1428 Turtleford, SK S0M 2Y0 Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD)

Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD) Camsell Uranium ´ Portage City Stony Lake Athasbasca Rapids Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park Cluff Lake Points Wollaston North Eagle Point Lake Airport McLean Uranium Mine Lake Cigar Lake Uranium Rabbit Lake Wollaston Mine Uranium Mine Lake McArthur River 955 Cree Lake Key Lake Uranium Reindeer Descharme Mine Lake Lake 905 Clearwater River Provincial Park Turnor 914 La Loche Lake Garson Black Lake Point Bear Creek Southend Michel Village St. Brabant George's Buffalo Hill Patuanak Narrows 102 Seabee 155 Gold Mine Santoy Missinipe Lake Gold Sandy Ile-a-la-crosse Pinehouse Bay Stanley Mission Wadin Little Bay Pelican Amyot Lac La Ronge Jans Bay La Plonge Provincial Park Narrows Cole Bay 165 La Ronge Beauval Air Napatak Keeley Ronge Tyrrell Lake Jan Lake Lake 55 Sturgeon-Weir Creighton Michel 2 Callinan Point 165 Dore Denare Lake Tower Meadow Lake Provincial Park Beach Beach 106 969 916 Ramsey Green Bay Weyakwin East 55 Sled Trout Lake Lake 924 Lake Little 2 Bear Lake 55 Prince Albert Timber National Park Bay Prince Albert Whelan Cumberland Little Bay Narrow Hills " Peck Fishing G X Delaronde National Park Provincial Park House NortLahke rLnak eTowns Northern Hamlets ...Northern Settlements 123 Creighton Black Point Descharme Lake 120 Noble's La Ronge Cole Bay Garson Lake 2 Point Dore Lake Missinipe # Jans Bay Sled Lake Ravendale Northern Villages ! Peat Bog Michel Village Southend ...Resort Subdivisions 55 Air Ronge Patuanak Stanley Mission Michel Point Beaval St. George's Hill Uranium -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Requirements Department of Geography

A GEOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF· THE COMMERCIAL FISHING INDUSTRY IN NORTHERN SASKATCHEWAN: AN EXAMPLE OF RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial FUlfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Geography by Gary Ronald Seymour Saskatoon, Saskatchewan . 1971. G.R. Seymour Acknowledgements The author is grateful to the many people in the Geography Department, University of Saskatchewan, in government and in the fishing industry who provided valuable information and advice in the preparation of this thesis. The author is particularly indebted to: Dr. J.H. I Richards and E.N. Shannon, Department of Geography, Univer�ity of Saskatchewan; G. Couldwell and P. Naftel, Fisheries Branch, Department of Natural Resources, Saskatchewan and F.M. Atton, Chief Biologist, Fisheries Branch, Department of Natural Resources, Saskatoon. Gratitude is also expressed to the Institute of Northern Studies, University of Saskatchewan whose financial assistance made collection of field data for this thesis possible. A special debt of gratitude is extended to my advisor, Dr. R.M. Bone of the Geography Department, University of Saskatchewan, whose willing direction and advice provided valuable assistance in the organization and writing of the thesis. i Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 II. THE RESOURCE BASE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 Factors Affecting Total Productivity •••••• 3 Methods of Commercial Fishing •••• • • • • • • 7 1) Summer -

Geology and Geochemistry of the Schist Lake Mine Area, Flin Flon, Manitoba (Part of NTS 63K12) by E.M Cole1, S.J

GS-2 Geology and geochemistry of the Schist Lake mine area, Flin Flon, Manitoba (part of NTS 63K12) by E.M Cole1, S.J. Piercey1,2 and H.L. Gibson1 Cole, E.M., Piercey, S.J. and Gibson, H.L. 2008: Geology and geochemistry of the Schist Lake mine area, Flin Flon, Manitoba (part of NTS 63K12); in Report of Activities 2008, Manitoba Science, Technology, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 18–28. Summary regarding the stratigraphic and The goal of this two-year research project is to temporal relationship between the characterize and describe the Schist Lake and Mandy main deposits — Callinan, Triple volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposits and their 7 and Flin Flon — and the Schist hostrocks, and to determine if these VMS deposits are Lake–Mandy deposits located just a few kilometres to the time-stratigraphic equivalent to those occurring in the south of the main camp. The objective of this research main Flin Flon camp. The first year of this project focused is to document the volcanic and structural setting of the on the area around the Schist Lake mine, where detailed Schist Lake and Mandy deposits, document the alteration lithofacies and alteration facies maps were completed, types associated with these deposits, and ultimately along with detailed field descriptions of each lithofacies. compare the Schist Lake and Mandy deposits with the The mine is hosted by a succession of mafic and felsic aforementioned current VMS deposits of the main Flin volcaniclastic rocks that were deposited in a basin envi- Flon camp. ronment. Geochemical