Geospatial Analysis of Controls on Subglacial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

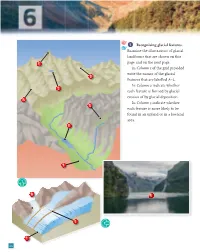

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Calving Processes and the Dynamics of Calving Glaciers ⁎ Douglas I

Earth-Science Reviews 82 (2007) 143–179 www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Calving processes and the dynamics of calving glaciers ⁎ Douglas I. Benn a,b, , Charles R. Warren a, Ruth H. Mottram a a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, KY16 9AL, UK b The University Centre in Svalbard, PO Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Norway Received 26 October 2006; accepted 13 February 2007 Available online 27 February 2007 Abstract Calving of icebergs is an important component of mass loss from the polar ice sheets and glaciers in many parts of the world. Calving rates can increase dramatically in response to increases in velocity and/or retreat of the glacier margin, with important implications for sea level change. Despite their importance, calving and related dynamic processes are poorly represented in the current generation of ice sheet models. This is largely because understanding the ‘calving problem’ involves several other long-standing problems in glaciology, combined with the difficulties and dangers of field data collection. In this paper, we systematically review different aspects of the calving problem, and outline a new framework for representing calving processes in ice sheet models. We define a hierarchy of calving processes, to distinguish those that exert a fundamental control on the position of the ice margin from more localised processes responsible for individual calving events. The first-order control on calving is the strain rate arising from spatial variations in velocity (particularly sliding speed), which determines the location and depth of surface crevasses. Superimposed on this first-order process are second-order processes that can further erode the ice margin. -

A Globally Complete Inventory of Glaciers

Journal of Glaciology, Vol. 60, No. 221, 2014 doi: 10.3189/2014JoG13J176 537 The Randolph Glacier Inventory: a globally complete inventory of glaciers W. Tad PFEFFER,1 Anthony A. ARENDT,2 Andrew BLISS,2 Tobias BOLCH,3,4 J. Graham COGLEY,5 Alex S. GARDNER,6 Jon-Ove HAGEN,7 Regine HOCK,2,8 Georg KASER,9 Christian KIENHOLZ,2 Evan S. MILES,10 Geir MOHOLDT,11 Nico MOÈ LG,3 Frank PAUL,3 Valentina RADICÂ ,12 Philipp RASTNER,3 Bruce H. RAUP,13 Justin RICH,2 Martin J. SHARP,14 THE RANDOLPH CONSORTIUM15 1Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 2Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA 3Department of Geography, University of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland 4Institute for Cartography, Technische UniversitaÈt Dresden, Dresden, Germany 5Department of Geography, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada E-mail: [email protected] 6Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA 7Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 8Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden 9Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria 10Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 11Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA 12Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 13National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA 14Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 15A complete list of Consortium authors is in the Appendix ABSTRACT. The Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) is a globally complete collection of digital outlines of glaciers, excluding the ice sheets, developed to meet the needs of the Fifth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for estimates of past and future mass balance. -

Glaciers and Their Significance for the Earth Nature - Vladimir M

HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE – Vol. IV - Glaciers and Their Significance for the Earth Nature - Vladimir M. Kotlyakov GLACIERS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE EARTH NATURE Vladimir M. Kotlyakov Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Keywords: Chionosphere, cryosphere, glacial epochs, glacier, glacier-derived runoff, glacier oscillations, glacio-climatic indices, glaciology, glaciosphere, ice, ice formation zones, snow line, theory of glaciation Contents 1. Introduction 2. Development of glaciology 3. Ice as a natural substance 4. Snow and ice in the Nature system of the Earth 5. Snow line and glaciers 6. Regime of surface processes 7. Regime of internal processes 8. Runoff from glaciers 9. Potentialities for the glacier resource use 10. Interaction between glaciation and climate 11. Glacier oscillations 12. Past glaciation of the Earth Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Past, present and future of glaciation are a major focus of interest for glaciology, i.e. the science of the natural systems, whose properties and dynamics are determined by glacial ice. Glaciology is the science at the interfaces between geography, hydrology, geology, and geophysics. Not only glaciers and ice sheets are its subjects, but also are atmospheric ice, snow cover, ice of water basins and streams, underground ice and aufeises (naleds). Ice is a mono-mineral rock. Ten crystal ice variants and one amorphous variety of the ice are known.UNESCO Only the ice-1 variant has been – reve EOLSSaled in the Nature. A cryosphere is formed in the region of interaction between the atmosphere, hydrosphere and lithosphere, and it is characterized bySAMPLE negative or zero temperature. CHAPTERS Glaciology itself studies the glaciosphere that is a totality of snow-ice formations on the Earth's surface. -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Contribution of Lake-Effect Snow to the Catskill Mountains Snowpack

74th EASTERN SNOW CONFERENCE Ottawa, Ontario, CANADA 2017 Contribution of Lake-Effect Snow to the Catskill Mountains Snowpack DOROTHY K. HALL,1,2 NICOLO E. DIGIROLAMO,3 ALLAN FREI4 ABSTRACT Meltwater from snow that falls in the Catskill Mountains in southern New York contributes to reservoirs that supply drinking water to approximately nine million people in New York City. Using the NOAA National Ice Center’s Interactive Multisensor Snow and Ice Mapping System (IMS) 4km snow maps, we have identified at least 32 lake-effect (LE) storms emanating from Lake Erie and/or Lake Ontario that deposited snow in the Catskill/Delaware Watershed in the Catskill Mountains of southern New York State between 2004 and 2017. This represents a large underestimate of the contribution of LE snow to the Catskills snowpack because many of the LE snowstorms are not visible in the IMS snow maps when they travel over snow-covered terrain. Most of the LE snowstorms that we identified originate from Lake Ontario but quite a few originate from both Erie and Ontario, and a few from Lake Erie alone. Using satellite, meteorological and reanalysis data we identify conditions that contributed to LE snowfall in the Catskills. Clear skies following some of the storms permitted measurement of the extent of snow cover in the watershed using multiple satellite sensors. IMS maps tend to overestimate the extent of snow compared to MODerate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Landsat- derived snow-cover extent maps. Using this combination of satellite and meteorological data, we can begin to quantify the important contribution of LE snow to the Catskills Mountain snowpack. -

Edges of Ice-Sheet Glaciology

Important Things Ice Sheets Do, but Ice Sheet Models Don’t Dr. Robert Bindschadler Chief Scientist Hydrospheric and Biospheric Sciences Laboratory NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [email protected] I’ll talk about • Why we need models – from a non-modeler • Why we need good models – recent observations have destroyed confidence in present models • Recent ice-sheet surprises • Responsible physical processes “…understanding of (possible future rapid dynamical changes in ice flow) is too limited to assess their likelihood or provide a best estimate or an upper bound for sea level rise.” IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Summary for Policy Makers (2007) Future Sea Level is likely underestimated A1B IPCC AR4 (2007) Ice Sheets matter Globally Source: CReSIS and NASA Land area lost by 1-meter rise in sea level Impact of 1-meter sea level rise: Source: Anthoff et al., 2006 Maldives 20th Century Greenland Ice Sheet Sea level Change (mm/a) -1 0 +1 accumulation 450 Gt/a melting 225 Gt/a ice flow 225 Gt/a Approximately in “mass balance” 21st Century Greenland Ice Sheet Sea level Change (mm/a) -1 0 +1 accumulation melting ice flow Things could get a little better or a lot worse Increased ice flow will dominate the future rate of change A History Lesson • Less ice in HIGH SEA LEVEL Less warmer ice climates • Ice sheets More shrink faster LOW ice than they TEMPERATURE WARM grow • Sea level change is not COLD THEN NOW smooth Time Decreasing Mass Balance (Source: Luthcke et al., unpub.) Greenland Ice Sheet Mass Balance GREENLAND (Source: IPCC FAR) Antarctic Ice Sheet Mass Balance ANTARCTICA (Source: IPCC FAR) Pace of ice sheet changes have astonished experts is the common agent behind these changes Ice sheets HATE water! Fastest Flow at the Edges Interior: 1000’s meters thick and slow Perimeter: 100’s meters thick and fast Source: Rignot and Thomas Response time and speed of perturbation propagation are tied directly to ice flow speed 1. -

Ilulissat Icefjord

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1149.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ilulissat Icefjord DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: DENMARK CRITERIA: N (i) (iii) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (i): The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of a stage in the Earth’s history: the last ice age of the Quaternary Period. The ice-stream is one of the fastest (19m per day) and most active in the world. Its annual calving of over 35 cu. km of ice accounts for 10% of the production of all Greenland calf ice, more than any other glacier outside Antarctica. The glacier has been the object of scientific attention for 250 years and, along with its relative ease of accessibility, has significantly added to the understanding of ice-cap glaciology, climate change and related geomorphic processes. Criterion (iii): The combination of a huge ice sheet and a fast moving glacial ice-stream calving into a fjord covered by icebergs is a phenomenon only seen in Greenland and Antarctica. Ilulissat offers both scientists and visitors easy access for close view of the calving glacier front as it cascades down from the ice sheet and into the ice-choked fjord. The wild and highly scenic combination of rock, ice and sea, along with the dramatic sounds produced by the moving ice, combine to present a memorable natural spectacle. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Located on the west coast of Greenland, 250-km north of the Arctic Circle, Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord (40,240-ha) is the sea mouth of Sermeq Kujalleq, one of the few glaciers through which the Greenland ice cap reaches the sea. -

Crag-And-Tail Features on the Amundsen Sea Continental Shelf, West Antarctica

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on November 30, 2016 Crag-and-tail features on the Amundsen Sea continental shelf, West Antarctica F. O. NITSCHE1*, R. D. LARTER2, K. GOHL3, A. G. C. GRAHAM4 & G. KUHN3 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 4College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) On parts of glaciated continental margins, especially the inner leads to its characteristic tapering and allows formation of the sec- shelves around Antarctica, grounded ice has removed pre-existing ondary features. Multiple, elongated ridges in the tail could be sedimentary cover, leaving subglacial bedforms on eroded sub- related to the unevenness of the top of the ‘crags’. Secondary, strates (Anderson et al. 2001; Wellner et al. 2001). While the smaller crag-and-tail features might reflect variations in the under- dominant subglacial bedforms often follow a distinct, relatively lying substrate or ice-flow dynamics. uniform pattern that can be related to overall trends in palaeo- While the length-to-width ratio of crag-and-tail features in this ice flow and substrate geology (Wellner et al. 2006), others are case is much lower than for drumlins or elongate lineations, the more randomly distributed and may reflect local substrate varia- boundary between feature classes is indistinct. -

Glacial Processes and Landforms-Transport and Deposition

Glacial Processes and Landforms—Transport and Deposition☆ John Menziesa and Martin Rossb, aDepartment of Earth Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada; bDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Introduction 2 2 Towards deposition—Sediment transport 4 3 Sediment deposition 5 3.1 Landforms/bedforms directly attributable to active/passive ice activity 6 3.1.1 Drumlins 6 3.1.2 Flutes moraines and mega scale glacial lineations (MSGLs) 8 3.1.3 Ribbed (Rogen) moraines 10 3.1.4 Marginal moraines 11 3.2 Landforms/bedforms indirectly attributable to active/passive ice activity 12 3.2.1 Esker systems and meltwater corridors 12 3.2.2 Kames and kame terraces 15 3.2.3 Outwash fans and deltas 15 3.2.4 Till deltas/tongues and grounding lines 15 Future perspectives 16 References 16 Glossary De Geer moraine Named after Swedish geologist G.J. De Geer (1858–1943), these moraines are low amplitude ridges that developed subaqueously by a combination of sediment deposition and squeezing and pushing of sediment along the grounding-line of a water-terminating ice margin. They typically occur as a series of closely-spaced ridges presumably recording annual retreat-push cycles under limited sediment supply. Equifinality A term used to convey the fact that many landforms or bedforms, although of different origins and with differing sediment contents, may end up looking remarkably similar in the final form. Equilibrium line It is the altitude on an ice mass that marks the point below which all previous year’s snow has melted. -

Year Book of the Holland Society of New-York

w r 974.7 PUBLIC LIBRARY M. L, H71 FORT WAYNE & ALLEM CO., IND. 1916 472087 SENE^AUOGV C0L.L-ECT!0N EN COUNTY PUBLIC lllllilllllilll 3 1833 01147 7442 TE^R BOOK OF The Holland Society OF New Tork igi6 PREPARED BY THE RECORDING SECRETARY Executive Office 90 West Street new york city Copyright 1916 The Holland Society of New York : CONTENTS DOMINE SELYNS' RECORDS: PAGE Introduction I Table of Contents 2 Discussion of Previous Editions 10 Text 21 Appendixes 41 Index 81 ADMINISTRATION Constitution 105 By-Laws 112 Badges 116 Accessions to Library 123 MEMBERSHIP: 472087 Former Officers 127 Committees 1915-16 142 List of Members 14+ Necrology 172 MEETINGS: Anniversary of Installation of First Mayor and Board of Aldermen 186 Poughkeepsie 199 Smoker 202 Hudson County Branch 204 Banquet 206 Annual Meeting 254 New Officers, 1916 265 In Memoriam 288 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Gerard Beekman—Portrait Frontispiece New York— 1695—Heading Cut i Selyns' Seal— Initial Letter i Dr. James S. Kittell— Portrait 38 North Church—Historic Plate 43 Map of New York City— 1695 85 Hon. Francis J. Swayze— Portrait 104 Badge of the Society 116 Button of the Society 122 Hon. William G. Raines—Portrait 128 Baltus Van Kleek Homestead—Heading Cut. ... 199 Eagle Tavern at Bergen—Heading Cut 204 Banquet Layout 207 Banquet Ticket 212 Banquet Menu 213 Ransoming Dutch Captives 213 New Amsterdam Seal— 1654 216 New York City Seal— 1669 216 President Wilson Paying Court to Father Knick- erbocker 253 e^ c^^ ^ 79c^t'*^ C»€^ THE HOLLAND SOCIETY TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction. Description and History of the Manuscript Volume. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ...............................................................