Before Albany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohawk River Watershed – HUC-12

ID Number Name of Mohawk Watershed 1 Switz Kill 2 Flat Creek 3 Headwaters West Creek 4 Kayaderosseras Creek 5 Little Schoharie Creek 6 Headwaters Mohawk River 7 Headwaters Cayadutta Creek 8 Lansing Kill 9 North Creek 10 Little West Kill 11 Irish Creek 12 Auries Creek 13 Panther Creek 14 Hinckley Reservoir 15 Nowadaga Creek 16 Wheelers Creek 17 Middle Canajoharie Creek 18 Honnedaga 19 Roberts Creek 20 Headwaters Otsquago Creek 21 Mill Creek 22 Lewis Creek 23 Upper East Canada Creek 24 Shakers Creek 25 King Creek 26 Crane Creek 27 South Chuctanunda Creek 28 Middle Sprite Creek 29 Crum Creek 30 Upper Canajoharie Creek 31 Manor Kill 32 Vly Brook 33 West Kill 34 Headwaters Batavia Kill 35 Headwaters Flat Creek 36 Sterling Creek 37 Lower Ninemile Creek 38 Moyer Creek 39 Sixmile Creek 40 Cincinnati Creek 41 Reall Creek 42 Fourmile Brook 43 Poentic Kill 44 Wilsey Creek 45 Lower East Canada Creek 46 Middle Ninemile Creek 47 Gooseberry Creek 48 Mother Creek 49 Mud Creek 50 North Chuctanunda Creek 51 Wharton Hollow Creek 52 Wells Creek 53 Sandsea Kill 54 Middle East Canada Creek 55 Beaver Brook 56 Ferguson Creek 57 West Creek 58 Fort Plain 59 Ox Kill 60 Huntersfield Creek 61 Platter Kill 62 Headwaters Oriskany Creek 63 West Kill 64 Headwaters South Branch West Canada Creek 65 Fly Creek 66 Headwaters Alplaus Kill 67 Punch Kill 68 Schenevus Creek 69 Deans Creek 70 Evas Kill 71 Cripplebush Creek 72 Zimmerman Creek 73 Big Brook 74 North Creek 75 Upper Ninemile Creek 76 Yatesville Creek 77 Concklin Brook 78 Peck Lake-Caroga Creek 79 Metcalf Brook 80 Indian -

"Smackdown on the Hudson" the Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany

"Smackdown on the Hudson" The Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany Lesson Procedures Essential question: How was the colony of New Netherland ruled by the Dutch West India Company and the patroons? Grade 7 Content Understandings, New York State Standards: Social Studies Standards This lesson covers European Exploration and Colonization of the Americas and Life in Colonial Communities, focusing on settlement patterns and political life in New Netherland. By studying the conflict between the Petrus Stuyvesant and the Brant van Slichtenhorst, students will consider the sources of historic documents and evaluate their reliability. Common Core Standards: Reading Standards By analyzing historic documents, students will develop essential reading, writing, and critical thinking skills. They will read and analyze informational texts and draw inferences from those texts. Students will explain what happened and why based on information from the readings. Additionally, as a class, students will discuss general academic and domain- specific words or phrases relevant to the unit. Speaking and Listening Standards Students will engage in group and teacher-led collaborative discussions, using textual evidence to pose hypotheses and respond to specific questions. They will also report to the class on their group’s assigned topic, explaining their ideas, analyses, and observations and citing reasons and evidence to support their claims. New Netherland Institute New Netherland Research Center "Smackdown on the Hudson" 2 Writing Standards To conclude this lesson, students write a letter to the editor of the Rensselaerwijck Times that draws evidence from informational texts and supports claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. Historical Context: In 1614, soon after the founding of the New Netherland Company (predecessor to the West India Company, est. -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

Risk Assessment: Asset Identification & Characterization

This Working Draft Submittal is a preliminary draft document and is not to be used as the basis for final design, construction or remedial action, or as a basis for major capital decisions. Please be advised that this document and associated deliverables have not undergone internal reviews by URS. SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: ASSET IDENTIFICATION & CHARACTERIZATION SECTION 3b - RISK ASSESSMENT: IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF ASSETS Overview An inventory of geo-referenced assets in Rensselaer County has been created in order to identify and characterize property and persons potentially at risk from the identified hazards. Understanding the type and number of hazards that exist in relation to known hazard areas is an important step in the process of formulating the risk assessment and quantifying the vulnerability of the municipalities that make up Rensselaer County. For this plan, six key categories of assets have been mapped and analyzed using GIS data provided by Rensselaer County, with some additional data drawn from other public sources: 1. Improved property: This category includes all developed properties according to parcel data provided by Rensselaer County and equalization rates from the New York State Office of Real Property Services. Impacts to improved properties are presented as a percentage of each community’s total value of improvements that may be exposed to the identified hazards. 2. Emergency facilities: This category covers all facilities dedicated to the management and response of emergency or disaster situations, and includes emergency operations centers (EOCs), fire stations, police stations, ambulance stations, shelters, and hospitals. Impacts to these assets are presented by tabulating the number of each type of facility present in areas that may be exposed to the identified hazards. -

Hudson Valley Community College

A.VII.4 Articulation Agreement: Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC) to College of Staten Island (CSI) Associate in Science in Business Administration (HVCC) to Bachelor of Science: International Business Concentration (CSI) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND A. SENDING AND RECEIVING INSTITUTIONS Sending Institution: Hudson Valley Community College Department: Program: School of Business and Liberal Arts Business Administration Degree: Associate in Science (AS) Receiving Institution: College of Staten Island Department: Program: Lucille and Jay Chazanoff School of Business Business: International Business Concentration Degree: Bachelor of Science (BS) B. ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS FOR SENIOR COLLEGE PROGRAM Minimum GPA- 2.5 To gain admission to the College of Staten Island, students must be skill certified, meaning: • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in a credit-bearing mathematics course of at least 3 credits • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in freshmen composition, its equivalent, or a higher-level English course Total transfer credits granted toward the baccalaureate degree: 63-64 credits Total additional credits required at the senior college to complete baccalaureate degree: 56-57 credits 1 C. COURSE-TO-COURSE EQUIVALENCIES AND TRANSFER CREDIT AWARDED HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND Credits Course Number & Title Credits Course Number & Title Credits Awarded CORE RE9 UIREM EN TS: ACTG 110 Financial Accounting 4 -

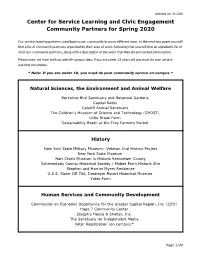

Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020

Updated Jan 16 2020 Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020 Our service learning partners contribute to our community in many different ways. In the next two pages you will find a list of community partners organized by their area of work. Following that you will find an alphabetic list of all of our community partners, along with a description of the work that they do and contact information. Please note, we have both on and off-campus sites. If you are under 18 years old you must do your service learning on campus. * Note: If you are under 18, you must do your community service on-campus * Natural Sciences, the Environment and Animal Welfare Berkshire Bird Sanctuary and Botanical Gardens Capital Roots Catskill Animal Sanctuary The Children’s Museum of Science and Technology (CMOST) Little Brook Farm Sustainability Booth at the Troy Farmers Market History New York State Military Museum– Veteran Oral History Project New York State Museum Hart Cluett Museum in Historic Rensselaer County Schenectady County Historical Society / Mabee Farm Historic Site Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence U.S.S. Slater DE 766, Destroyer Escort Historical Museum Yates Farm Human Services and Community Development Commission on Economic Opportunity for the Greater Capital Region, Inc. (CEO) Hope 7 Community Center Joseph’s House & Shelter, Inc. The Sanctuary for Independent Media Voter Registration (on campus)* Page 1/20 Updated Jan 16 2020 Literacy and adult education English Conversation Partners Program (on campus)* Learning Assistance Center (on campus)* Literacy Volunteers of Rensselaer County The RED Bookshelf Daycare, school and after-school programs, children’s activities Albany Free School Albany Police Athletic League (PAL), Inc. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT New York State Assembly Carl E. Heastie Speaker Committee on Environmental Conservation Steve Englebright Chairman THE ASSEMBLY CHAIRMAN STATE OF NEW YORK Committee on Environmental Conservation COMMITTEES ALBANY Education Energy Higher Education Rules COMMISSIONS STEVEN ENGLEBRIGHT 4th Assembly District Science and Technology Suffolk County Water Resource Needs of Long Island MEMBER Bi-State L.I. Sound Marine Resource Committee N.Y.S. Heritage Area Advisory Council December 15, 2017 Honorable Carl E. Heastie Speaker of the Assembly Legislative Office Building, Room 932 Albany, NY 12248 Dear Speaker Heastie: I am pleased to submit to you the 2017 Annual Report of the Assembly Standing Committee on Environmental Conservation. This report describes the legislative actions and major issues considered by the Committee and sets forth our goals for future legislative sessions. The Committee addressed several important issues this year including record funding for drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, increased drinking water testing and remediation requirements and legislation to address climate change. In addition, the Committee held hearings to examine water quality and the State’s clean energy standard. Under your leadership and with your continued support of the Committee's efforts, the Assembly will continue the work of preserving and protecting New York's environmental resources during the 2018 legislative session. Sincerely, Steve Englebright, Chairman Assembly Standing Committee on Environmental Conservation DISTRICT OFFICE: 149 Main Street, East Setauket, New York 11733 • 631-751-3094 ALBANY OFFICE: Room 621, Legislative Office Building, Albany, New York 12248 • 518-455-4804 Email: [email protected] 2017 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION Steve Englebright, Chairman Committee Members Deborah J. -

Freshwater Fishing: a Driver for Ecotourism

New York FRESHWATER April 2019 FISHINGDigest Fishing: A Sport For Everyone NY Fishing 101 page 10 A Female's Guide to Fishing page 30 A summary of 2019–2020 regulations and useful information for New York anglers www.dec.ny.gov Message from the Governor Freshwater Fishing: A Driver for Ecotourism New York State is committed to increasing and supporting a wide array of ecotourism initiatives, including freshwater fishing. Our approach is simple—we are strengthening our commitment to protect New York State’s vast natural resources while seeking compelling ways for people to enjoy the great outdoors in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. The result is sustainable economic activity based on a sincere appreciation of our state’s natural resources and the values they provide. We invite New Yorkers and visitors alike to enjoy our high-quality water resources. New York is blessed with fisheries resources across the state. Every day, we manage and protect these fisheries with an eye to the future. To date, New York has made substantial investments in our fishing access sites to ensure that boaters and anglers have safe and well-maintained parking areas, access points, and boat launch sites. In addition, we are currently investing an additional $3.2 million in waterway access in 2019, including: • New or renovated boat launch sites on Cayuga, Oneida, and Otisco lakes • Upgrades to existing launch sites on Cranberry Lake, Delaware River, Lake Placid, Lake Champlain, Lake Ontario, Chautauqua Lake and Fourth Lake. New York continues to improve and modernize our fish hatcheries. As Governor, I have committed $17 million to hatchery improvements. -

NY Excluding Long Island 2017

DISCONTINUED SURFACE-WATER DISCHARGE OR STAGE-ONLY STATIONS The following continuous-record surface-water discharge or stage-only stations (gaging stations) in eastern New York excluding Long Island have been discontinued. Daily streamflow or stage records were collected and published for the period of record, expressed in water years, shown for each station. Those stations with an asterisk (*) before the station number are currently operated as crest-stage partial-record station and those with a double asterisk (**) after the station name had revisions published after the site was discontinued. Those stations with a (‡) following the Period of Record have no winter record. [Letters after station name designate type of data collected: (d) discharge, (e) elevation, (g) gage height] Period of Station Drainage record Station name number area (mi2) (water years) HOUSATONIC RIVER BASIN Tenmile River near Wassaic, NY (d) 01199420 120 1959-61 Swamp River near Dover Plains, NY (d) 01199490 46.6 1961-68 Tenmile River at Dover Plains, NY (d) 01199500 189 1901-04 BLIND BROOK BASIN Blind Brook at Rye, NY (d) 01300000 8.86 1944-89 BEAVER SWAMP BROOK BASIN Beaver Swamp Brook at Mamaroneck, NY (d) 01300500 4.42 1944-89 MAMARONECK RIVER BASIN Mamaroneck River at Mamaroneck, NY (d) 01301000 23.1 1944-89 BRONX RIVER BASIN Bronx River at Bronxville, NY (d) 01302000 26.5 1944-89 HUDSON RIVER BASIN Opalescent River near Tahawus, NY (d) 01311900 9.02 1921-23 Fishing Brook (County Line Flow Outlet) near Newcomb, NY (d) 0131199050 25.2 2007-10 Arbutus Pond Outlet -

New York Fishing Regulations Guide: 2017-18

NEW YORK Freshwater FISHING 2017–18 O cial Volume 9, Issue No. 1 April 2017 Regulations Guide Fishing Lake Champlain www.dec.ny.gov Most regulations are in eect April 1, 2017 through March 31, 2018 Message from the Governor New York: A State of Angling Opportunity If you are an angler, you know how lucky you are to live in New York. The Empire State is unmatched in the quality and diversity of our fish species, and ranks fifth in the nation for total acreage of freshwater fishing locations. There are so many opportunities to get out and enjoy this important sport, and I have made it a priority to ensure that all New Yorkers have access to the State’s abundant fishing resources. That is why the NY is Open for Fishing and Hunting initiative has provided more than $4 million over the last three years to rehabilitate existing boat launches and construct new launches across the state. In addition, New York continues to make great progress toward our goal of establishing 50 new or improved land and water access sites. In 2016, we opened new universally accessible fishing piers and hand carry launches on the Esopus Creek in Ulster County and Looking Glass Pond in Schoharie County. We refurbished the Dunkirk Harbor Fishing Pier in Chautauqua County, which now provides access for users of all abilities to the outstanding fishing found in this area of Lake Erie. 2017 will see the opening of a brand new boat launch on Meacham Lake in Franklin County and updated facility on the northern end of Cayuga Lake. -

New York State Department of State

November 25, 2020 DEPARTMENT OF STATE Vol. XLII Division of Administrative Rules Issue 47 NEW YORK STATE REGISTER INSIDE THIS ISSUE: D Inland Trout Stream Fishing Regulations D Minimum Standards for Form, Content, and Sale of Health Insurance, Including Standards of Full and Fair Disclosure D Surge and Flex Health Coordination System Availability of State and Federal Funds Executive Orders Financial Reports State agencies must specify in each notice which proposes a rule the last date on which they will accept public comment. Agencies must always accept public comment: for a minimum of 60 days following publication in the Register of a Notice of Proposed Rule Making, or a Notice of Emergency Adoption and Proposed Rule Making; and for 45 days after publication of a Notice of Revised Rule Making, or a Notice of Emergency Adoption and Revised Rule Making in the Register. When a public hearing is required by statute, the hearing cannot be held until 60 days after publication of the notice, and comments must be accepted for at least 5 days after the last required hearing. When the public comment period ends on a Saturday, Sunday or legal holiday, agencies must accept comment through the close of business on the next succeeding workday. For notices published in this issue: – the 60-day period expires on January 24, 2021 – the 45-day period expires on January 9, 2021 – the 30-day period expires on December 5, 2020 ANDREW M. CUOMO GOVERNOR ROSSANA ROSADO SECRETARY OF STATE NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF STATE For press and media inquiries call: (518) 474-0050 For State Register production, scheduling and subscription information call: (518) 474-6957 E-mail: [email protected] For legal assistance with State Register filing requirements call: (518) 474-6740 E-mail: [email protected] The New York State Register is now available on-line at: www.dos.ny.gov/info/register.htm The New York State Register (ISSN 0197 2472) is published weekly. -

Episodes from a Hudson River Town Peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’S 4,200-Foot Slide Mountain, May Have Poked up out of the Frozen Terrain

1 Prehistoric Times Our Landscape and First People The countryside along the Hudson River and throughout Greene County always has been a lure for settlers and speculators. Newcomers and longtime residents find the waterway, its tributaries, the Catskills, and our hills and valleys a primary reason for living and enjoying life here. New Baltimore and its surroundings were formed and massaged by the dynamic forces of nature, the result of ongoing geologic events over millions of years.1 The most prominent geographic features in the region came into being during what geologists called the Paleozoic era, nearly 550 million years ago. It was a time when continents collided and parted, causing upheavals that pushed vast land masses into hills and mountains and complementing lowlands. The Kalkberg, the spiny ridge running through New Baltimore, is named for one of the rock layers formed in ancient times. Immense seas covered much of New York and served as collect- ing pools for sediments that consolidated into today’s rock formations. The only animals around were simple forms of jellyfish, sponges, and arthropods with their characteristic jointed legs and exoskeletons, like grasshoppers and beetles. The next integral formation event happened 1.6 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch when the Laurentide ice mass developed in Canada. This continental glacier grew unyieldingly, expanding south- ward and retreating several times, radically altering the landscape time and again as it traveled. Greene County was buried. Only the highest 5 © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany 6 / Episodes from a Hudson River Town peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’s 4,200-foot Slide Mountain, may have poked up out of the frozen terrain.