Self-Analysis Ernest Krenek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tocc0298notes.Pdf

ERNST KRENEK AT THE PIANO: AN INTRODUCTION by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek was born on 23 August 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and grew up in a house that overlooked the original gravesites of Beethoven and Schubert. His parents hailed from Čáslav, in what was then Bohemia, but had moved to the city when his father, an officer in the commissary corps of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army, had received a posting there. Vienna, the self-styled ‘City of Music’, considered itself to be the well-spring of a musical tradition synonymous with the core values of western classical music, and so it was no matter that neither of Krenek’s parents was a practising musician of any stature: Ernst was exposed to music – and lots of it – from a very young age. Later in life he recalled with wonder the fact that ‘walking along the paths that Beethoven had walked, or shopping in the house in which Mozart had written “Don Giovanni”, or going to a movie across the street from where Schubert was born, belonged to the routine experiences of my childhood’.1 As befitting an officer’s son, Krenek received formal musical instruction from a young age, in particular piano lessons and instruction in music theory. The existence of a well-stocked music hire library in the city enabled him to become, by his mid-teens, acquainted with the entire standard Classical and Romantic piano literature of the day. His formal schooling coincidentally introduced Krenek to the literature of classical antiquity and helped ensure that his appreciation of this music would be closely associated in his own mind with his appreciation of western history and classical culture more generally. -

Krenek Ernest

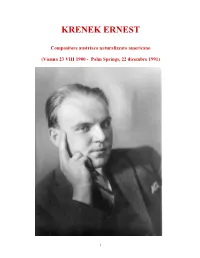

KRENEK ERNEST Compositore austriaco naturalizzato americano (Vienna 23 VIII 1900 - Palm Springs, 22 dicembre 1991) 1 Allievo dal 1916 al 1920 di F. Schreker all'Accademia musicale di Vienna, passò poi alla Hochschule fur Musik di Berlino, dove continuò gli studi con Schreker, ed entrò in proficuo contatto di lavoro con Busoni, A. Schnabel ed altri esponenti del mondo musicale della capitale tedesca. Sposata la figlia di Mahler, Anna (1923) si stabilì in Svizzera ma due anni dopo divorziò e dal 1925 al 1927, su invito di P. Bekker, fu nominato consigliere artistico dell'Opera di Kassel, mettendosi in luce con numerose composizioni teatrali e strumentali ed iniziando un'intensa attività pubblicistica come collaboratore musicale della "Frankfurter Zeitung" e dal 1933 della "Wiener Zeitung”. Ottenuto un successo di portata internazionale con l'opera Jonny spielt auf, dal 1928 si stabilì a Vienna dedicandosi quasi esclusivamente alla composizione, anche qui a contatto con gli ambienti artistici d'avanguardia (Berg, Webern, K. Kraus). Nel 1937 emigrò in America, dove nel 1939 ottenne una cattedra nel Vassar College di Poughkeepsie, presso New York. Dal 1945 ha avuto la cittadinanza americana. Dal 1942 al 1947 ha insegnato nell'Università di Saint Paul, stabilendosi poi a Los Angeles. Dopo la guerra rientrò spesso in Europa, per corsi di composizione, conferenze e concerti. Musicista assai sensibile ai più attuali problemi estetici e di linguaggio, il suo arco creativo rispecchia l'evoluzione spesso contraddittoria delle correnti dell'avanguardia musicale del secolo. L'insegnamento di Schreker lo ha avvicinato nella prima gioventù ad una sorta di espressionismo temperato in senso tardo-romantico, ma ben presto si liberò da quell'influenza per avvicinarsi alle più diverse esperienze musicali. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

The Happiest Years Sonatas for Violin Solo by Artur Schnabel and Eduard Erdmann

The Happiest Years Sonatas for Violin Solo by Artur Schnabel and Eduard Erdmann Judith Ingolfsson, Violin The Happiest Years Sonatas for Violin Solo by Artur Schnabel a nd Eduard Erdmann Judith Ingolfsson, Violin Artur Schnabel (1882–1951) Sonata for Violin Solo (1919) 01 I. Langsam, sehr frei und leidenschaftlich . (09'23) 02 II. In kräftig-fröhlichem Wanderschritt, durchweg sehr lebendig . (03'10) 03 III. Zart und anmutig, durchaus ruhig . (11'27) 04 IV. Äußerst rasch (Prestissimo) . (06'39) 05 V. Sehr langsame Halbe, mit feierlichem ernstem Ausdruck, doch stets schlicht . (15'58) Eduard Erdmann (1896–1958) Sonata for Violin Solo, Op. 12 (1921) 06 I. Ruhig – Fließend – Ruhig . (07'48) 07 II. Allegretto scherzando – Trio: Einfach, wie eine Volksweise . (04'17) 08 III. Langsam . (02'39) 09 IV. Lebendig . (03'44) Total Time . (65'11) The Happiest Years he years from 1919 to 1924 in Berlin,” Artur Schnabel told an audience of stu- dents in 1945, “were, musically, the most stimulating and perhaps the happiest I ever experienced.” During this brief period of his life, the great pianist chose to T play fewer concerts and devote more time to composing. He was “happy” com- posing and considered it “a kind of hobby, or love aff air.” He was not interested in the “value” of his compositions, rather in the “activity.” In 1919 the atmosphere in Berlin was turbulent. The loss of the First World War, the No- vember Revolution, and the subsequent establishment of the Weimar Republic had created social disparity. Although theaters, cinemas, and cabarets abounded, and literary and artis- tic life displayed great vitality, there remained a striking contrast between the neon lights of Kurfürstendamm and the impoverished working-class areas. -

Römische Chorlyrik

RÖMISCHE CHORLYRIK Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) durch die Philosophische Fakultät der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf vorgelegt von Claudia Damm aus Düsseldorf Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jochem Küppers Prof. Dr. Michael Reichel Mündliche Prüfungen: 26.01.2006, 09.02.2006 1 D 61 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagung............................................................................................................2 Einleitung................................................................................................................3 1. Chorlyrik in Griechenland.............................................................................9 1.1 Überblick über die Chorlyrik ...................................................................9 1.1.1 Vorbemerkungen zum Begriff ‚Lyrik’ ...........................................9 1.1.2 Die einzelnen Chorliedgattungen..............................................13 1.1.3 Die Hauptvertreter der Chorlieddichtung...................................25 1.2 Die Chöre im Kult und im Drama..........................................................35 1.2.1 Die Chöre im Kult .....................................................................35 1.2.2 Die Chöre im Drama.................................................................40 2. Römische Chorlieder in der Zeit vor Catull ...............................................66 2.1 Die vorliterarische Phase......................................................................66 -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

Claudia Maurer Zenck

Claudia Maurer Zenck Publikationsliste A: Bücher Verfolgungsgrund: „Zigeuner“. Unbekannte Musiker und ihr Schicksal im „Dritten Reich“ (= Antifaschistische Literatur und Exilliteratur – Studien und Texte, Bd. 25, hg. v. Verein zur Förderung und Erforschung der antifaschistischen Literatur), Wien: Verlag der Theodor Kramer Gesellschaft, 2016 Mozarts Così fan tutte: dramma giocoso und deutsches Singspiel. Frühe Abschriften und frühe Aufführungen, Schliengen: edition argus, 2007 Vom Takt. Untersuchungen zur Theorie und kompositorischen Praxis im ausgehenden 18. und beginnenden 19. Jahrhundert, Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 2001 Ernst Krenek – ein Komponist im Exil, Wien: Lafite, 1980 Versuch über die wahre Art, Debussy zu analysieren (= Berliner musikwissenschaftliche Arbeiten 8), München / Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1974 B: Editionen Ernst Krenek. Frühe Lieder für Gesang und Klavier, 3 Hefte, Wien: Universal Edition, 2015 (mit Einleitung, Textteil, Kritischem Bericht) Ernst Krenek - Briefwechsel mit der Universal Edition (1921-1941), 2 Teile, Köln / Weimar / Wien: Böhlau, 2010 „'...la di Ella inaudita finezza'. Zur Entstehung der Varianti. Briefwechsel Luigi Nono – Rudolf Kolisch 1954–1957/58“, in: Schönberg & Nono. A Birthday Offering to Nuria on May 7, 2002, hg. v. Anna Maria Morazzoni, Florenz: Olschki, 2002, S. 267–315 Ernst Krenek: Die amerikanischen Tagebücher 1937–1942. Dokumente aus dem Exil (Hg. u. Übers.), Wien / Köln / Weimar: Böhlau, 1992 Der hoffnungslose Radikalismus der Mitte. Briefwechsel Ernst Krenek – Friedrich T. Gubler 1928–1939 (Hg.), Wien / Köln: Böhlau, 1989 C: Herausgabe Younghi Pagh-Paan. Auf dem Weg zur musikalischen Symbiose, Mainz: Schott, 2020 (wird im Mai/Juni 2020 erscheinen) (zus. mit Gernot Gruber u. Matthias Schmidt:) Ernst Krenek – nicht nur Komponist (= Ernst Krenek Studien 7), Schliengen: edition argus, 2018 Musik, Bühne und Publikum. -

Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo

melbourne opera Part One of e Ring of the Nibelung WAGNER’S Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Richard Wagner Society (VIC) • Wagner Society (nsw) Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE) Fund melbourneopera.com Classic bistro wine – ethereal, aromatic, textural, sophisticated and so easy to pair with food. They’re wines with poise and charm. Enjoy with friends over a few plates of tapas. debortoli.com.au /DeBortoliWines melbourne opera WAGNER’S COMPOSER & LIBRETTIST RICHARD WAGNER First performed at Munich National Theatre, Munich, Germany on 22nd September 1869. Wotan BASS Eddie Muliaumaseali’i Alberich BARITONE Simon Meadows Loge TENOR James Egglestone Fricka MEZZO-SOPRANO Sarah Sweeting Freia SOPRANO Lee Abrahmsen Froh TENOR Jason Wasley Donner BASS-BARITONE Darcy Carroll Erda MEZZO-SOPRANO Roxane Hislop Mime TENOR Michael Lapina Fasolt BASS Adrian Tamburini Fafner BASS Steven Gallop Woglinde SOPRANO Rebecca Rashleigh Wellgunde SOPRANO Louise Keast Flosshilde MEZZO-SOPRANO Karen Van Spall Conductors Anthony Negus, David Kram FEB 5, 21 Director Suzanne Chaundy Head of Music Raymond Lawrence Set Design Andrew Bailey Video Designer Tobias Edwards Lighting Designer Rob Sowinski Costume Designer Harriet Oxley Set Build & Construction Manager Greg Carroll German Language Diction Coach Carmen Jakobi Company Manager Robbie McPhee Producer Greg Hocking AM MELBOURNE OPERA ORCHESTRA The performance lasts approximately 2 hours 25 minutes with no interval. Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and The role of Loge, performed by James Egglestone, is proudly supported by Expland (RISE) Fund – an Australian the Richard Wagner Society of Victoria. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0125 Notes

P ERNEST KRENEK: MUSIC FOR CHAMBER ORCHESTRA by Peter Tregear The Austrian-born composer Ernst Krenek (1900–91) has been described, with good reason, as a compositional ‘companion of the twentieth century’.1 Stretching over seventy years of productive life, his musical legacy encompasses most of the common forms of modern western art music, from string quartets and symphonies to opera and electronic music. Moreover, it engages with many of the key artistic movements of the day – from late Romanticism and Neo- classicism to abstract Expressionism and Post-modernism. The sheer scope of his music seems to reflect something profound about the condition of his turbulent times. The origins of Krenek’s extraordinary artistic disposition are to be found in the equally extraordinary circumstances into which he was born. He came to maturity in Vienna in the dying days of the First World War and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and, with its collapse in 1919, the cultural norms that had nurtured Vienna’s enviable musical reputation all but disappeared. In addition, by this time, new forms of transmission of mass culture, such as the wireless, gramophone and cinema, were transforming the ways and means by which cultural life could be both propagated and received. As an artist trying to come to terms with these changes, Krenek was doubly fortunate. Not only was he generally recognised as one of the most gifted composers of his generation; he was also an insightful thinker about music and its role in society. Right from the moment in 1921 when, in the face of growing tension between himself and his composition teacher Franz Schreker, he set out on a full-time career as a composer, he determined that he would be more than just as a passive reflector of the world around him; he would be both its witness and conscience. -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87392-5 - Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann, 1888-1976 Michael H. Kater Index More information Index 8 [Acht] Uhr-Blatt, Vienna, 56 Auguste Victoria, ex-queen of Portugal, 137 Abessynians, 273 Auguste Viktoria, Empress, 3, 9 Abravanel, Maurice, 207, 259–61, 287, 298 Austrian Honor Cross First Class, 278 Academy Awards, Hollywood, 232, 236 Austrian Republic, 44, 48, 51, 57, 64–66, 77, Adler, Friedrich, 38 85, 94, 97–99, 166, 307–8 Adolph, Paul, 110–11 Austrian State Theaters, 220 Adventures at the Lido, 234 Austrofascism, 94, 166–69, 308 Agfa company, 185 Aida, 266, 276 Bachur, Max, 15, 18–21, 28, 30–31, 33, Albert Hall, London, 117 42–43 Alceste, 269 Baker, Janet, 251 Alda, Frances, 68 Baker, Josephine, 94 Aldrich, Richard, 69 Baklanoff, Georges, 43 Alexander, king of Yugoslavia, 170 Ballin, Albert, 16, 30, 77, 304 Alice in Wonderland, 193 Balogh, Erno,¨ 147–49, 151, 158, 164, Alien Registration Act, 211 180–81 Allen, Fred, 230 Bampton, Rose, 183, 206, 245 Allen, Judith, 253 Banklin oil refinery, Santa Barbara, 212 Althouse, Paul, 174 Barnard College, Columbia University, New Altmeyer, Jeannine, 261 York, 151 Alvin Theater, New York, 204 Barsewisch, Bernhard von, 1, 13, 35, 285, Alwin, Karl, 102, 106–7, 189, 196 298, 302, 319n172, 343n269 American Committee for Christian German Barsewisch, Elisabeth von, nee´ Gans Edle zu Refugees, 211 Putlitz, 13, 82, 285, 295 American Legion, 68 Bartels, Elise, 11, 14 An die ferne Geliebte, 217 Barthou, Louis, 170 Anderson, Bronco Bill, 198 -

Poetik Und Dramaturgie Der Komischen Operette

9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Albert Gier ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette ‘ 9 Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen Romanische Literaturen und Kulturen hrsg. von Dina De Rentiies, Albert Gier und Enrique Rodrigues-Moura Band 9 2014 ‚ Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick Poetik und Dramaturgie der komischen Operette Albert Gier 2014 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de/ abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbibliothek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sons- tigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press Titelbild: Johann Strauß, Die Fledermaus, Regie Christof Loy, Bühnenbild und Kostüme Herbert Murauer, Oper Frankfurt (2011). Bild Monika Rittershaus. Abdruck mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Monika Rittershaus (Berlin). © University of Bamberg Press Bamberg 2014 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 1867-5042 ISBN: 978-3-86309-258-0 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-259-7 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-106760 Inhalt Einleitung 7 Kapitel I: Eine Gattung wird besichtigt 17 Eigentlichkeit 18; Uneigentliche Eigentlichkeit