Britain Italy and the Early Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi Italia, Primer ministro (1993-1994) y presidente de la República (1999-2006) Duración del mandato: 18 de Maig de 1999 - de de Nacimiento: Livorno, provincia de Livorno, región de Toscana, 09 de Desembre de 1920 Defunción: Roma, región de Lacio, 16 de Setembre de 2016</p> Partido político: sin filiación Professió: Funcionario de banca Resumen http://www.cidob.org 1 of 3 Biografía Cursó estudios en Pisa en su Escuela Normal Superior, por la que se diplomó en 1941, y en su Universidad, por la que en 1946 obtuvo una doble licenciatura en Derecho y Letras. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial sirvió en el Ejército italiano y tras la caída de Mussolini en 1943 estuvo con los partisanos antinazis. En 1945 militó en el Partido de Acción de Ferruccio Parri, pero pronto se desvinculó de cualquier organización política. En 1946 entró a trabajar por la vía de oposiciones en el Banco de Italia, institución donde desarrolló toda su carrera hasta la cúspide. Sucesivamente fue técnico en el departamento de investigación económica (1960-1970), jefe del departamento (1970-1973), secretario general del Banco (1973-1976), vicedirector general (1976-1978), director general (1978-1979) y, finalmente, gobernador (1979-1993). Considerado un economista de formación humanista, Ciampi salvaguardó la independencia del banco del Estado y se labró una imagen de austeridad y apego al trabajo. Como titular representó a Italia en las juntas de gobernadores de diversas instituciones financieras internacionales. Con su elección el 26 de abril de 1993 por el presidente de la República Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (por primera vez sin consultar a los partidos) para reemplazar a Giuliano Amato, Ciampi se convirtió en el primer jefe de Gobierno técnico, esto es, no adscrito a ninguna formación, desde 1945, si bien algunos líderes políticos insistieron en sus simpatías democristianas. -

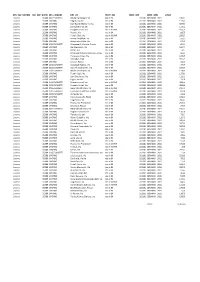

Lista Location English.Xlsx

LOCATIONS LIST Postal City Name Address Code ABANO TERME 35031 DIBRA KLODIANA VIA GASPARE GOZZI 3 ABBADIA SAN SALVATORE 53021 FABBRINI CARLO PIAZZA GRAMSCI 15 ABBIATEGRASSO 20081 BANCA DI LEGNANO VIA MENTANA ACCADIA 71021 NIGRO MADDALENA VIA ROMA 54 ACI CATENA 95022 PRINTEL DI STIMOLO PRINCIPATO VIA NIZZETI 43 ACIREALE 95024 LANZAFAME ALESSANDRA PIAZZA MARCONI 12 ACIREALE 95024 POLITI WALTER VIA DAFNICA 104 102 ACIREALE 95024 CERRA DONATELLA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE 143 ACIREALE 95004 RIV 6 DI RIGANO ANGELA MARIA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE II 69 ACQUAPENDENTE 01021 BONAMICI MANUELA VIA CESARE BATTISTI 1 ACQUASPARTA 05021 LAURETI ELISA VIA MARCONI 40 ACQUEDOLCI 98076 MAGGIORE VINCENZO VIA RICCA SALERNO 43 ACQUI TERME 15011 DOC SYSTEM VIA CARDINAL RAIMONDI 3 ACQUI TERME 15011 RATTO CLAUDIA VIA GARIBALDI 37 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND CORSO BAGNI 102 106 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND VIA AMENDOLA 31 ACRI 87041 MARCHESE GIUSEPPE ALDO MORO 284 ADRANO 95031 LA NAIA NICOLA VIA A SPAMPINATO 13 ADRANO 95031 SANTANGELO GIUSEPPA PIAZZA UMBERTO 8 ADRANO 95031 GIULIANO CARMELA PIAZZA SANT AGOSTINO 31 ADRIA 45011 ATTICA S R L RIVIERA GIACOMO MATTEOTTI 5 ADRIA 45011 SANTINI DAVIDE VIA CHIEPPARA 67 ADRIA 45011 FRANZOSO ENRICO CORSO GIUSEPPE MAZZINI 73 AFFI 37010 NIBANI DI PAVONE GIULIO AND C VIA DANZIA 1 D AGEROLA 80051 CUOMO SABATO VIA PRINCIPE DI PIEMONTE 11 AGIRA 94011 BIONDI ANTONINO PIAZZA F FEDELE 19 AGLIANO TERME 14041 TABACCHERIA DELLA VALLE VIA PRINCIPE AMEDEO 27 29 AGNA 35021 RIVENDITA N 7 VIA MURE 35 AGRIGENTO -

Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy

Dr. Francesco Gallo OUTSTANDING FAMILIES of Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy from the XVI to the XX centuries EMIGRATION to USA and Canada from 1880 to 1930 Padua, Italy August 2014 1 Photo on front cover: Graphic drawing of Aiello of the XVII century by Pietro Angius 2014, an readaptation of Giovan Battista Pacichelli's drawing of 1693 (see page 6) Photo on page 1: Oil painting of Aiello Calabro by Rosario Bernardo (1993) Photo on back cover: George Benjamin Luks, In the Steerage, 1900 Oil on canvas 77.8 x 48.9 cm North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the Elizabeth Gibson Taylor and Walter Frank Taylor Fund and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.12 2 With deep felt gratitude and humility I dedicate this publication to Prof. Rocco Liberti a pioneer in studying Aiello's local history and author of the books: "Ajello Calabro: note storiche " published in 1969 and "Storia dello Stato di Aiello in Calabria " published in 1978 The author is Francesco Gallo, a Medical Doctor, a Psychiatrist, a Professor at the University of Maryland (European Division) and a local history researcher. He is a member of various historical societies: Historical Association of Calabria, Academy of Cosenza and Historic Salida Inc. 3 Coat of arms of some Aiellese noble families (from the book by Cesare Orlandi (1734-1779): "Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti compendiose notizie", Printer "Augusta" in Perugia, 1770) 4 SUMMARY of the book Introduction 7 Presentation 9 Brief History of the town of Aiello Calabro -

Media E Informazione - Lunedi 1 E Martedì 2 Giugno 2020 (N

1 Università IULM Osservatorio su comunicazione pubblica, public branding e trasformazione digitale Direttore scientifico: prof. Stefano Rolando ([email protected]) Comunicazione e situazione di crisi https://www.iulm.it/it/sites/osservatorio-comunicazione-in-tempo-di-crisi/comunicare-in-tempo-di-crisi Media e informazione - Lunedi 1 e Martedì 2 giugno 2020 (n. 90-n.91) Rallentamento Il 2 giugno del 1946, attraverso referendum istituzionale, gli italiani scelsero di porre fine alla forma monarchica del Paese, anche a causa della commistione con il ventennio fascista, optando per la forma repubblicana. Con 12.182.855 voti, il 54,3% dei votanti scelse la Repubblica, con 10.362.709, il 45,7% dei votanti scelse la Monarchia. L’affluenza fu dell’89,08%. Solo l’11% degli italiani scelse l’astensione. La carta geo-politica dell’Italia fu molto segnata da quel voto: il centro-nord ebbe una dominante di voto repubblicano, il centro-sud e isole ebbe una dominante di voto monarchico. Il governo in carica fino a fine 1945 presieduto dall’azionista Ferruccio Parri e il successivo presieduto dal dc Alcide De Gasperi prepararono l’insediamento dell’Assemblea costituente che – con le presidenze del socialista Giuseppe Saragat e poi del comunista Umberto Terracini – si insediò il 26 giugno del 1946 e terminò i suoi lavori, un mese dopo la promulgazione in G.U. della Costituzione repubblicana, il 31 gennaio del 1948. Nel frattempo il Paese fu governato con tre mandati consecutivi dall’esecutivo presieduto da De Gasperi. Alla Costituente la DC ebbe il 35,2% dei voti, i socialisti il 20,7%, i comunisti il 18,9%, i liberali il 6,8%, i “qualunquisti” il 5,3%, i repubblicani il 4,4% gli azionisti l’1,5%. -

Sandro Pertini

Sandro Pertini Alessandro Pertini è nato a Stella (Savona) il 25 settembre 1896. Laureato in giurisprudenza e in scienze sociali. Coniugato con Carla Voltolina. Ha partecipato alla prima guerra mondiale; ha intrapreso la professione forense e, dopo la prima condanna a otto mesi di carcere per la sua attività politica, nel 1926 è condannato a cinque anni di confino. Sottrattosi alla cattura, si è rifugiato a Milano e successivamente in Francia, dove ha chiesto e ottenuto asilo politico, lavorando a Parigi. Anche in Francia ha subito due processi per la sua attività politica. Tornato in Italia nel 1929, è stato arrestato e nuovamente processato dal tribunale speciale per la difesa dello Stato e condannato a 11 anni di reclusione. Scontati i primi sette, è stato assegnato per otto anni al confino: ha rifiutato di impetrare la grazia anche quando la domanda è stata firmata da sua madre. Tornato libero nell'agosto 1943, è entrato a far parte del primo esecutivo del Partito socialista. Catturato dalla SS, è stato condannato a morte. La sentenza non ha luogo. Nel 1944 è evaso dal carcere assieme a Giuseppe Saragat, ed ha raggiunto Milano per assumere la carica di segretario del Partito Socialista nei territori occupati dal Tedeschi e poi dirigere la lotta partigiana: è stato insignito della Medaglia d'Oro. Conclusa la lotta armata, si è dedicato alla vita politica e al giornalismo. E' stato eletto Segretario del Partito Socialista Italiano di unità proletaria nel 1945. E' stato eletto Deputato all'Assemblea Costituente. E' stato eletto Senatore della Repubblica nel 1948 e presidente del relativo gruppo parlamentare. -

Italiani in Jugoslavia

10 febbraio 2008 Giornata del ricordo: italiani in Jugoslavia In occasione della quarta Giornata del ricordo, la Fondazione memoria della deportazione e l’Istituto nazionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione in Italia (Insmli) invitano a partecipare alla presentazione del libro L’occupazione allegra: gli italiani in Jugoslavia 1941-1943 (Carocci editore). Opera del giovane storico torinese Eric Gobetti, il volume ricostruisce la vicenda di un conflitto totale, guerra civile fra opposte fazioni e nazionalità jugoslave e guerra di liberazione contro gli occupanti. Tutt’altro che “allegra”, la presenza militare italiana fu caratterizzata da terribili stragi e violente rappresaglie contro i civili ma anche da un tentativo di mantenere il controllo del territorio attraverso la collaborazione di mediatori locali, sia serbi che croati. Gobetti ricostruisce questo quadro complesso attraverso lo studio di due realtà locali, le regioni di Knin e Mostar, facenti parte dello Stato collaborazionista croato. Da queste basi, utilizzando fonti documentarie sia italiane sia jugoslave, l’autore prova a rispondere ad alcuni interrogativi fondamentali che riguardano la debolezza del sistema d’occupazione italiano, la capacità dei partigiani jugoslavi di battere forze preponderanti, l’origine del mito degli italiani brava gente. Il libro sarà presentato giovedì 7 febbraio 2008 alle ore 17.30 presso la Fondazione memoria della deportazione, Biblioteca Archivio "Pina e Aldo Ravelli", via Dogana 3, Milano (02 87383240, [email protected]). Insieme all’autore saranno presenti il professor Luigi Ganapini (Università di Bologna, Fondazione Isec) e il professor Marco Cuzzi, autore di L'occupazione italiana della Slovenia 1941-1943 (SME Ufficio Storico). Istituto nazionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione in Italia viale Sarca 336, palazzina 15 - 20126 Milano, tel. -

Criticism of “Fascist Nostalgia” in the Political Thought of the New Right

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS WRATISLAVIENSIS No 3866 Studia nad Autorytaryzmem i Totalitaryzmem 40, nr 3 Wrocław 2018 DOI: 10.19195/2300-7249.40.3.6 JOANNA SONDEL-CEDARMAS ORCID: 0000-0002-3037-9264 Uniwersytet Jagielloński Criticism of “fascist nostalgia” in the political thought of the New Right The seizure of power by the National Liberation Committee on 25th April, 1945 and the establishment of the republic on 2nd June, 1946 constituted the symbolic end to Mussolini’s dictatorship that had lasted for more than 20 years. However, it emerged relatively early that fascism was not a defi nitively closed chapter in the political and social life of Italy. As early as June of 1946, after the announcement of a presidential decree granting amnesty for crimes committed during the time of the Nazi-Fascist occupation between 1943 and 1945, the country saw a withdrawal from policies repressive towards fascists.1 Likewise, the national reconciliation policy gradually implemented in the second half of the 1940s by the government of Alcide De Gasperi, aiming at pacifying the nation and fostering the urgent re- building of the institution of the state, contributed to the emergence of ambivalent approaches towards Mussolini’s regime. On the one hand, Italy consequently tried to build its institutional and political order in clear opposition towards fascism, as exemplifi ed, among others, by a clause in the Constitution of 1947 that forbade the establishment of any form of fascist party, as well as the law passed on 20th June, 1 Conducted directly after the end of WW II, the epurazione action (purifi cation) that aimed at uprooting fascism, was discontinued on 22nd June 1946, when a decree of president Enrico De Nicola granting amnesty for crimes committed during the Nazi-Fascist occupation of Italy between 1943–1945 was implemented. -

Monitoraggio Gennaio 2021.Pdf

DES_IMP_DISTRIB COD_IMP_DISTRIB DES_COMUNE DES_VIA PARTE_IMP MESE_ISPE MESE_ISPE2 LUNGH Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Alcide De Gasperi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 108,54 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fulgidi, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,83 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Don David Albertario, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 659,93 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Carabinieri, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,18 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Giorgio La Pira, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 185,25 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Rossini, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 68,70 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fratelli Gigli, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 258,57 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Enrico Bartelloni, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 55,55 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Alessandro Volta, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 67,65 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Di Vittorio, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 81,15 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO San Francesco, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 100,71 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Azzati, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 9,12 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia, Largo rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 66,16 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Francesco Crispi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 127,26 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO D'Azeglio, Scali rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 301,29 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Cavour, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 34,07 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Romita, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 37,79 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Niccolò Machiavelli, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 -

Sanela Schmid Deutsche Und Italienische Besatzung Im Unabhängigen Staat Kroatien Bibliotheks- Und Informationspraxis

Sanela Schmid Deutsche und italienische Besatzung im Unabhängigen Staat Kroatien Bibliotheks- und Informationspraxis Herausgegeben von Klaus Gantert und Ulrike Junger Band 66 Sanela Schmid Deutsche und italienische Besatzung im Unabhängigen Staat Kroatien 1941 bis 1943/45 Publiziert mit Unterstützung des Schweizerischen Nationalfonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. ISBN 978-3-11-062031-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-062383-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-062036-8 Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952843 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110623833 © 2020 Sanela Schmid, publiziert von Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Dieses Buch ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com, https:// www.doabooks.org und https://www.oapen.org Einbandabbildung: © Znaci.net. Deutsche Einheiten, die im Juni 1943 von den Italienern das Kommando über die Stadt Mostar erhalten. Typesetting: bsix information exchange GmbH, Braunschweig Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Für meine Großeltern, Mina und Jusuf Bešlagić Vorwort Dieses Buch ist die überarbeitete Fassung meiner Dissertation, die im November 2011 von der Universität Bern angenommen wurde. Es konnte nur entstehen, weil mich sehr viele Personen dabei unterstützt haben. Ihnen allen gilt mein aufrichtiger Dank. Zu allererst ist meine Doktormutter, Marina Cattaruzza, zu nennen, die an mich und das Thema geglaubt und das ganze Projekt mit Klug- heit, Scharfsinn und Witz über die Jahre begleitet hat. -

Italy's Atlanticism Between Foreign and Internal

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S ATLANTICISM BETWEEN FOREIGN AND INTERNAL POLITICS Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: In spite of being a defeated country in the Second World War, Italy was a founding member of the Atlantic Alliance, because the USA highly valued her strategic importance and wished to assure her political stability. After 1955, Italy tried to advocate the Alliance’s role in the Near East and in Mediterranean Africa. The Suez crisis offered Italy the opportunity to forge closer ties with Washington at the same time appearing progressive and friendly to the Arabs in the Mediterranean, where she tried to be a protagonist vis a vis the so called neo- Atlanticism. This link with Washington was also instrumental to neutralize General De Gaulle’s ambitions of an Anglo-French-American directorate. The main issues of Italy’s Atlantic policy in the first years of “centre-left” coalitions, between 1962 and 1968, were the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy as a result of the Cuban missile crisis, French policy towards NATO and the EEC, Multilateral [nuclear] Force [MLF] and the revision of the Alliance’ strategy from “massive retaliation” to “flexible response”. On all these issues the Italian government was consonant with the United States. After the period of the late Sixties and Seventies when political instability, terrorism and high inflation undermined the Italian role in international relations, the decision in 1979 to accept the Euromissiles was a landmark in the history of Italian participation to NATO. -

"Sulla Scissione Socialdemocratica Del 1947"

"SULLA SCISSIONE SOCIALDEMOCRATICA DEL 1947" 26-04-2018 - STORIE & STORIE La storiografia politica é ormai compattamente schierata nel giudicare validi, anche perché - cosí si dice - confermati dalla storia, i motivi che, nel gennaio 1947, portarono alla scissione detta „di Palazzo Barberini", che l´11 gennaio di quell´anno diede vita alla socialdemocrazia italiana. Il PSIUP (1), che era riuscito a riunire nello stesso partito tutte le "anime" del socialismo italiano, si spacco´ allora in due tronconi: il PSI di Nenni e il PSDI (2) di Saragat. I due leader, nel corso del precedente congresso di Firenze dell´ 11-17 aprile1946, avevano pronunciato due discorsi che, per elevatezza ideologica e per tensione ideale, sono degni di figurare nella storia del socialismo, e non solo di quello italiano. Il primo, Nenni, aveva marcato l´accento sulla necessitá di salvaguardare l´unitá della classe lavoratrice, in un momento storico in cui i tentativi di restaurazione capitalista erano ormai evidenti; il secondo aveva messo l´accento sulla necessitá di tutelare l´autonomia socialista, l´unica capace di costruire il socialismo nella democrazia, in un momento in cui l´ombra dello stalinismo si stendeva su tutta l´Europa centrale e orientale. Pochi mesi dopo, si diceva, la drammatica scissione tra „massimalisti" e „riformisti" (3), che la storia, o meglio, gli storici, avrebbero poi giudicato necessaria e lungimirante, persino provvidenziale. Essi, infatti, hanno dovuto registrare il trionfo del riformismo, ormai predicato anche dai nipotini di Togliatti e dagli italoforzuti. „Il termine riformista é oggi talmente logorato dall´uso, dall´abuso e dal cattivo uso, che ha perso ogni significato" (4). -

Sergio Mattarella

__________ Marzo 2021 Indice cronologico dei comunicati stampa SEZIONE I – DIMISSIONI DI CORTESIA ......................................................................... 9 Presidenza Einaudi...........................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Gronchi ..........................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Segni ..............................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Saragat.........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Leone ...........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Pertini ..........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Cossiga ........................................................................................................................11 Presidenza Ciampi .........................................................................................................................11 Presidenza Mattarella ....................................................................................................................11 SEZIONE II – DIMISSIONI EFFETTIVE ........................................................................