Alamo Area Experience Plan Update with Historic Annotations Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The French Texans

Texans One and All The French Texans Although a French flag of some sort is represented in “six flags over Tex- as” displays, France never—in any sense of political control or official claims—flew a flag over Texas and never gave her own citizens strong reasons for emigration. However, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, did make one foray west of the drainage of the Mississippi, and General Charles Lallemand did lead a short-lived military colony into East Texas. France, in the New World, was more interested in trade than settlement and was often distracted by continental European problems. The nation was neither equipped for colonial ventures nor had that much interest Revised 2013 in the western Gulf of Mexico. Nevertheless, in 1685 the young Sieur de La Salle landed at Matagorda Bay, Texas, some 600 miles west of his target: the Mississippi River. The few colonists he brought were to found a colony at the mouth of the Mississippi, to which France did have a claim, and thus tie down France's claims that, for a time, stretched from Canada to the Gulf—in theory. Encountering storms and perhaps suffering from bad navigation, the ships found the Spanish coast. Navigation in those days could determine, with an exactness of perhaps 30 miles on a good day, Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle position north and south. But the day was not good, and the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico stretches more east and west. In those days, east and west positions on a rotating globe were hard to determine. -

The Philip Nolan Expeditions When They First Heard of His Actions, Spanish Officials Thought That Philip Nolan Was Searching for Wealth

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 3 Unrest and Revolution Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1. The Spanish feared U.S. agents were active in Texas. • Philip Nolan 2. Mexico began a fight for independence in 1810. • filibusters 3. Filibusters and rebels tried to take control of Texas. • Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla Why It Matters Today • José Gutiérrez de Lara In the late 1700s some U.S. citizens fought to free Texas • Republican Army of the North and Mexico from Spain. Use current events sources to • siege find information about U.S. involvement in foreign • Battle of Medina conflicts today. • James Long TEKS: 2D, 17C, 19A, The Story Continues 19B, 21B, 21D, 21E, 22D To Philip Nolan, the mustangs roaming the Texas plains gleamed like gold. Horses were valuable items, and in Texas, myNotebook they ran free. All you had to do was catch them. Nolan Use the annotation became a mustanger, capturing wild horses in Texas and Text Guide: “Teaching” text shouldtools never in go yourbeyond thiseBook guide on any side. driving them to Louisiana. There he sold them at a hefty to take notes on the struggle for Mexi- profit. Then Spanish officials heard rumors of a U.S. plot can independence to invade northern New Spain. Was Nolan a U.S. spy? and its effects in Texas. The Philip Nolan Expeditions When they first heard of his actions, Spanish officials thought that Philip Nolan was searching for wealth. Nolan, a U.S. citizen, had first Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: come to Texas in 1791 as a mustang trader. -

The Siege & Battle of the Alamo

The Siege & Battle of the Alamo It is often difficult for visitors who come to the Alamo to imagine that a historic battle took place here. The buildings and streets hide one of the nation’s most important battlefields. I’d like to take you back to that time when the Alamo was a Texian fort deep in Mexican Texas. Hopefully when I’ve finished you will have a better understanding of why so many people have a feeling of reverence for the Alamo and the men who died here. Texas was in revolt 1836. Within months of General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s becoming president in 1833, he instructed the Mexican Congress to throw out the Federal Constitution and established a Centralist government with himself as its leader. While Santa Anna proclaimed himself the “Napoleon of the West,” his opponents had other names for him like tyrant, despot, and dictator. Most Anglo-Texans, or Texians as they were called, had tried to support the Mexican government after coming to Texas. Accepting Mexican citizenship and the Roman Catholic religion seemed small concessions for the chance to purchase land for 12 cents an acre. For the Mexican government, the plan to colonize Texas with Americans actually proved too successful when an 1829 census revealed that Texians outnumbered Tejanos, or Mexican-Texans, nearly ten to one. Distrust grew on both sides. Many Texians believed themselves underrepresented in Mexico City and asked for separate statehood from Coahuila. Mexican officials saw this as a prelude to independence and began to crack down on Texas, strengthening military garrisons at key towns. -

Lone Star Chemistry Soluxons

Lone Star Chemistry Soluons Lone Star Chemistry Soluons iBook: hps://itunes.apple.com/us/book/lone-star-chemistry-soluons/id635036317?mt=11 Abstract Calling all nave Texans and those who got here as fast as you could! A notable bull rider once said, "It ain't braggin', if it's true!" This class explores the facts, ficon, and folklore of Texas as they relate to the study of chemistry. The stories imparted serve to make chemistry engaging and you'll get to leave with all the bragging rights that make Texas and Texans extraordinary. We do get to have our cake and eat it, too! What Startd in Texas # Has Changed te World# Part I Emeritus College Spring 2015 Diana Mason, PhD, ACSF (rered) Professor Emeritus, Department of Chemistry University of North Texas April 14, 2015 IntroducAon • Interests – Research – Chemistry Educaon – Teaching – Chemistry – Service – Chemical Demonstraons; Teacher PD • Passion – Texas history – facts, ficon, and folklore Schedule • April 14: Texas on the World’s Stage • April 16: Early Statehood • April 21: 1880s to the Moon (Celebraon!) • April 23: Texas Today Texas Enters the World’s Stage 1. Braggin’ or True? Flags over Texas • Spain • France • 3 Nacogdoches flags • Mexico • Republic of Texas • Republic of Rio Grande • Confederate States of America • United States Spain’s Flag over Texas Flew over Texas from 1529 to 1684 France’s Flag over Texas Flew over Texas 1684 to 1689 Fort Saint Louis Fort St. Louis • French colony established 1685 – Near present-day Arenosa Creek and Matagorda Bay – By explorer Robert Cavelier de la Salle • Intended to sele: mouth of Mississippi River • Colony survived unl 1688 – Inez, Texas later developed here Houston County San Francisco de la Espada • 1689: First mission within the boundaries of Spanish Texas – Between Trinity and Red Rivers near Augusta in Houston County • Spanish authories found remnants of French selement – Fort St. -

Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan April2006 United States Department of the Interior FISH AND Wll...DLIFE SERVICE P.O. Box 1306 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 In Reply Refer To: R2/NWRS-PLN JUN 0 5 2006 Dear Reader: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is proud to present to you the enclosed Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) for the Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge). This CCP and its supporting documents outline a vision for the future of the Refuge and specifies how this unique area can be maintained to conserve indigenous wildlife and their habitats for the enjoyment of the public for generations to come. Active community participation is vitally important to manage the Refuge successfully. By reviewing this CCP and visiting the Refuge, you will have opportunities to learn more about its purpose and prospects. We invite you to become involved in its future. The Service would like to thank all the people who participated in the planning and public involvement process. Comments you submitted helped us prepare a better CCP for the future of this unique place. Sincerely, Tom Baca Chief, Division of Planning Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Sherman, Texas Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Planning Region 2 500 Gold SW Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Comprehensive conservation plans provide long-term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. -

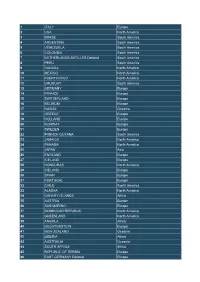

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Texas Life Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 3 Texas Life Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1. Most people in the Republic of Texas lived on farms or • land speculators ranches, though some lived in towns. • denominations 2. Games, literature, and art provided leisure activities. • circuit riders 3. Churches and schools were social centers. • academies Why It Matters Today • Th é o d o r e G e n t i l z Education was a major concern for people in the Republic. Use current events sources to learn about education in the United States and other countries today. TEKS: 4A, 9A, 19B, 19D, 21B, 22D The Story Continues Before making their journey to Texas, many immigrants myNotebook read a book by David Woodman Jr. called Guide to Texas Use the annotation Emigrants. This handy guide had many tips. He advised tools in your eBook to take notes on settlers to bring a reliable rifle and a strong dog. Woodman life in Texas during offered one other important recommendation. “It would be Bleed Art Guide: the period of the All bleeding art should be extended fully to the bleed guide. Republic. best to carry tents . for covering, until the house is built.” Woodman also said it was important to bring farming tools, a wagon, and comfortable clothing. Farming, Towns, and Transportation Most Texans, whether long-time residents or new immigrants, were Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: Folios, annos, standards, non-bleeding art, etc. should farmers and ranchers, although their farms varied widely in size. -

Chapter 10: the Alamo and Goliad

The Alamo and Goliad Why It Matters The Texans’ courageous defense of the Alamo cost Santa Anna high casualties and upset his plans. The Texas forces used the opportunity to enlist volunteers and gather supplies. The loss of friends and relatives at the Alamo and Goliad filled the Texans with determination. The Impact Today The site of the Alamo is now a shrine in honor of the defenders. People from all over the world visit the site to honor the memory of those who fought and died for the cause of Texan independence. The Alamo has become a symbol of courage in the face of overwhelming difficulties. 1836 ★ February 23, Santa Anna began siege of the Alamo ★ March 6, the Alamo fell ★ March 20, Fannin’s army surrendered to General Urrea ★ March 27, Texas troops executed at Goliad 1835 1836 1835 1836 • Halley’s Comet reappeared • Betsy Ross—at one time • Hans Christian Andersen published given credit by some first of 168 stories for making the first American flag—died 222 CHAPTER 10 The Alamo and Goliad Compare-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you compare and contrast the Alamo and Goliad—two important turning points in Texas independence. Step 1 Fold a sheet of paper in half from side to side. Fold it so the left edge lays about 1 2 inch from the right edge. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold it into thirds. Step 3 Unfold and cut the top layer only along both folds. This will make three tabs. Step 4 Label as shown. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

LOTS of LAND PD Books PD Commons

PD Commons From the collection of the n ^z m PrelingerTi I a JjibraryJj San Francisco, California 2006 PD Books PD Commons LOTS OF LAND PD Books PD Commons Lotg or ^ 4 I / . FROM MATERIAL COMPILED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE OF TEXAS BASCOM GILES WRITTEN BY CURTIS BISHOP DECORATIONS BY WARREN HUNTER The Steck Company Austin Copyright 1949 by THE STECK COMPANY, AUSTIN, TEXAS All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper. PRINTED AND BOUND IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PD Books PD Commons Contents \ I THE EXPLORER 1 II THE EMPRESARIO 23 Ml THE SETTLER 111 IV THE FOREIGNER 151 V THE COWBOY 201 VI THE SPECULATOR 245 . VII THE OILMAN 277 . BASCOM GILES PD Books PD Commons Pref<ace I'VE THOUGHT about this book a long time. The subject is one naturally very dear to me, for I have spent all of my adult life in the study of land history, in the interpretation of land laws, and in the direction of the state's land business. It has been a happy and interesting existence. Seldom a day has passed in these thirty years in which I have not experienced a new thrill as the files of the General Land Office revealed still another appealing incident out of the history of the Texas Public Domain. -

1872: Survivors of the Texas Revolution

(from the 1872 Texas Almanac) SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. The following brief sketches of some of the present survivors of the Texas revolution have been received from time to time during the past year. We shall be glad to have the list extended from year to year, so that, by reference to our Almanac, our readers may know who among those sketches, it will be seen, give many interesting incidents of the war of the revolution. We give the sketches, as far as possible, in the language of the writers themselves. By reference to our Almanac of last year, (1871) it will be seen that we then published a list of 101 names of revolutionary veterans who received the pension provided for by the law of the previous session of our Legislature. What has now become of the Pension law? MR. J. H. SHEPPERD’S ACCOUNT OF SOME OF THE SURVIVORS OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION. Editors Texas Almanac: Gentlemen—Having seen, in a late number of the News, that you wish to procure the names of the “veteran soldiers of the war that separated Texas from Mexico,” and were granted “pensions” by the last Legislature, for publication in your next year’s Almanac, I herewith take the liberty of sending you a few of those, with whom I am most intimately acquainted, and now living in Walker and adjoining counties. I would remark, however, at the outset, that I can give you but little information as to the companies, regiments, &c., in which these old soldiers served, or as to the dates, &c., of their discharges. -

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek by Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes

The Historical Narrative of San Pedro Creek By Maria Watson Pfeiffer and David Haynes [Note: The images reproduced in this internal report are all in the public domain, but the originals remain the intellectual property of their respective owners. None may be reproduced in any way using any media without the specific written permission of the owner. The authors of this report will be happy to help facilitate acquiring such permission.] Native Americans living along San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River 10,000 years ago were sustained by the swiftly flowing waterways that nourished a rich array of vegetation and wildlife. This virtual oasis in an arid landscape became a stopping place for Spanish expeditions that explored the area in the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was here that Governor Domingo Terán de los Ríos, accompanied by soldiers and priests, camped under cottonwood, oak, and mulberry trees in June 1691. Because it was the feast of Saint Anthony de Padua, they named the place San Antonio.1 In April 1709 an expedition led by Captain Pedro de Aguirre, including Franciscan missionaries Fray Isidro Félix de Espinosa and Fray Antonio Buenventura Olivares, visited here on the way to East Texas to determine the possibility of establishing new missions there. On April 13 Espinosa, the expedition’s diarist, wrote about a lush valley with a plentiful spring. “We named it Agua de San Pedro.” Nearby was a large Indian settlement and a dense growth of pecan, cottonwood, cedar elm, and mulberry trees. Espinosa recorded, “The river, which is formed by this spring, could supply not only a village, but a city, which could easily be founded here.”2 When Captain Domingo Ramón visited the area in 1716, he also recommended that a settlement be established here, and within two years Viceroy Marqués de Valero directed Governor Don Martín de Alarcón to found a town on the river.