Doctoral Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nord Stream 2

Updated August 24, 2021 Russia’s Nord Stream 2 Natural Gas Pipeline to Germany Nord Stream 2, a natural gas pipeline nearing completion, is which accounted for about 48% of EU natural gas imports expected to increase the volume of Russia’s natural gas in 2020. Russian gas exports to the EU were up 18% year- export capacity directly to Germany, bypassing Ukraine, on-year in the first quarter of 2021. Factors behind reliance Poland, and other transit states (Figure 1). Successive U.S. on Russian supply include diminishing European gas Administrations and Congresses have opposed Nord Stream supplies, commitments to reduce coal use, Russian 2, reflecting concerns about European dependence on investments in European infrastructure, Russian export Russian energy and the threat of increased Russian prices, and the perception of many Europeans that Russia aggression in Ukraine. The German government is a key remains a reliable supplier. proponent of the pipeline, which it says will be a reliable Figure 1. Nord Stream Gas Pipeline System source of natural gas as Germany is ending nuclear energy production and reducing coal use. Despite the Biden Administration’s stated opposition to Nord Stream 2, the Administration appears to have shifted its focus away from working to prevent the pipeline’s completion to mitigating the potential negative impacts of an operational pipeline. Some critics of this approach, including some Members of Congress and the Ukrainian and Polish governments, sharply criticized a U.S.-German joint statement on energy security, issued on July 21, 2021, which they perceived as indirectly affirming the pipeline’s completion. -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations

September 2017 FEUTURE Online Paper No. 5 The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations Nona Mikhelidze, IAI Nicolò Sartori, IAI Oktay F. Tanrisever, METU Theodoros Tsakiris, ELIAMEP Online Paper No. 5 “The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU -Turkey Relations ” ABSTRACT The Turkey-Russia-EU energy triangle is a relationship of interdependence and strategic compromise. However, Russian support for secessionism and erosion of state autonomy in the Caucasus and Eurasia has proven difficult to reconcile for western European states despite their energy dependence. Yet, Turkey has enjoyed an enhanced bilateral relationship with Russia, augmenting its position and relevance in a strategic energy relationship with the EU. The relationship between Ankara and Moscow is principally based on energy security and domestic business interests, and has largely remained stable in times of regional turmoil. This paper analyses the dynamics of Ankara-Moscow cooperation in order to understand which of the three scenarios in EU –Turkey relations – conflict, cooperation or convergence – could be expected to develop bearing in mind that the partnership between Turkey and Russia has become unpredictable. The intimacy of Turkish-Russia energy relations and EU-Russian regional antagonism makes transactional cooperation on energy demand the most likely of future scenarios. A scenario in which both Brussels and Ankara will try to coordinate their relations with Russia through a positive agenda, in order to exploit the interdependence emerging within the “triangle”. ÖZET Türkiye Rusya ve AB arasındaki enerji üçgeni bir karşılıklı bağımlılık ve stratejik uzlaşma ilişkisidir. Ancak, her ne kadar Rusya’ya enerji bağımlılıkları olsa da, Batı Avrupalı devletler için Rusya’nın Kafkasya ve Avrasyadaki ayrılıkçılığa ve devlet özerkliğinin erozyonuna verdiği desteğin kabullenilmesinin zor olduğu ortaya çıkmıştır. -

Terrestrial Ecology

Chapter 11: Terrestrial Ecology URS-EIA-REP-204635 Table of Contents 11 Terrestrial Ecology ................................................................................... 11-1 11.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 11-1 11.2 Scoping ............................................................................................................ 11-1 11.2.1 ENVIID ................................................................................................ 11-2 11.2.2 Stakeholder Engagement ...................................................................... 11-2 11.2.3 Analysis of Alternatives ......................................................................... 11-4 11.3 Spatial and Temporal Boundaries ........................................................................ 11-4 11.3.1 Spatial Boundaries ................................................................................ 11-4 11.3.2 Temporal Boundaries .......................................................................... 11-11 11.4 Baseline Data .................................................................................................. 11-11 11.4.1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 11-11 11.4.2 Secondary Data .................................................................................. 11-11 11.4.3 Data Gaps .......................................................................................... 11-14 -

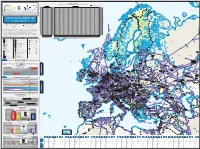

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

SCRSS Digest Spring 2011

Information Digest Spring 2011 Price £1.00 While it would be untrue to say that the Contents peoples of the union republics of the USSR were oppressed, national consciousness Russians and the Russian Language in was stifled. Languages and peoples had the Post-Soviet Space 1 been forcibly mixed together across a huge SCRSS News 4 territory equivalent to 15% of the globe. Soviet Memorial Trust Fund News 6 Following the Belovezha Accords, a new VTS for Russian and Soviet Studies 7 reality began to be built on this territory – Taking off into Space! 9 with sometimes unpredictable consequences. First Man in Space: Yuri Gagarin Visits the SCR, 13 July 1961 10 Geographically speaking, the republics of Reviews 11 the former Soviet Union formed four groups Listings 16 united by greater or lesser ethnic similarity, cultural and religious traditions: Baltic, East European, Transcaucasian and Central Asian2. What linked all these groups was having Moscow as the state capital, Russian Feature as the language of inter-ethnic communication and Russians constituting a significant proportion of the population of Russians and the Russian each republic. Attitudes towards this were ambiguous: if the Baltic peoples always felt Language in the Post- they had been forcibly annexed, the Soviet Space Georgians never considered themselves deceived or enslaved, having become part A personal view by Dr Nataliya of the Russian Empire voluntarily in the Rogozhina early 19th century. On 8 December 1991 the Agreement on the During the Soviet period a strict system Creation of the Commonwealth of existed by which every graduate of a higher Independent States (CIS) was signed by the educational institution was required to work heads of the three Soviet republics of for a three-year period wherever the Russia, Ukraine and Belorussia at the relevant ministry sent them. -

14 April 2020 Oil and Gas Sector of GEORGIA in the Transition Period

Teimuraz Gochitashvili Oil and Gas Sector of GEORGIA in the Transition Period TBILISI 2020 უაკ (UDC) 622.691 622.24 Teimuraz Gochitashvili OIL AND GAS SECTOR OF GEORGIA IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD Tbilisi, 2020 The publication deals with the current state of oil and gas sector, prospects for its development and energy security of Georgia; it also focuses on regional oil and gas potential, production and delivery prospects to the European market. Special attention is paid to the transit and inland transmission pipelines, their reliability and safety, preconditioning security of supply to local and European markets. It also highligths the issues of harmonization of Georgian energy legislation with the European one and institutional structures as well as the integration of the market into the single energy space, discussing the corresponding legal grounds. The information presented in this publication, including assessments of the current state of the sector and scenarios for the development of the natural gas market, reflects only the personal opinion of the author, is not related to his job responsibilities and not reproduce the views or positions of his employer or government bodies Editor - Dr. Teimuraz Javakhishvili Language Editor – Tekla Gabunia All rights reserved by the legislation of Georgia „Meridian“ Publishing House, 2020 ISBN 978-9941-25-866-4 2 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the help and support of my colleagues from Georgian Oil and Gas Corporation, including Dr. Soso Gudushauri, Dr. David Tsitsishvili. Ms. Liana Lomidze, Ms. Ia Goisashvili, Mr. Archil Dekanosidze, Mr. Suliko Tsintsadze, Mr. Irakli Chachibaia and others. I am also deeply indebted to many people, including those engaged in the energy sector of Georgia, who have discussed the issues in the publication. -

Central Asia Oil and Gas Industry - the External Powers’ Energy Interests in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Raimondi, Pier Paolo Working Paper Central Asia Oil and Gas Industry - The External Powers’ Energy Interests in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan Working Paper, No. 006.2019 Provided in Cooperation with: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) Suggested Citation: Raimondi, Pier Paolo (2019) : Central Asia Oil and Gas Industry - The External Powers’ Energy Interests in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, Working Paper, No. 006.2019, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM), Milano This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/211165 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

From South Stream to Turk Stream

FROM SOUTH STREAM TO TURK STREAM PROSPECTS FOR REROUTING OPTIONS AND FLOWS OF RUSSIAN GAS TO PARTS OF EUROPE AND TURKEY LUCA FRANZA VISITING ADDRESS POSTAL ADDRESS Clingendael 12 P.O. Box 93080 TEL +31 (0)70 - 374 67 00 2597 VH The Hague 2509 AB The Hague www.clingendaelenergy.com The Netherlands The Netherlands [email protected] CIEP PAPER 2015 | 05 CIEP is affiliated to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. CIEP acts as an independent forum for governments, non-governmental organizations, the private sector, media, politicians and all others interested in changes and developments in the energy sector. CIEP organizes lectures, seminars, conferences and roundtable discussions. In addition, CIEP members of staff lecture in a variety of courses and training programmes. CIEP’s research, training and activities focus on two themes: • European energy market developments and policy-making; • Geopolitics of energy policy-making and energy markets CIEP is endorsed by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, BP Europe SE- BP Nederland, Coöperatieve Centrale Raiffeisen-Boerenleenbank B.A. ('Rabobank'), Delta N.V., GDF SUEZ Energie Nederland N.V., GDF SUEZ E&P Nederland B.V., Eneco, EBN B.V., Essent N.V., Esso Nederland B.V., GasTerra B.V., N.V. Nederlandse Gasunie, Heerema Marine Contractors Nederland B.V., ING Commercial Banking, Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij B.V., N.V. NUON Energy, TenneT TSO B.V., Oranje-Nassau Energie B.V., Havenbedrijf Rotterdam N.V., Shell Nederland B.V., TAQA Energy B.V.,Total E&P Nederland B.V., Koninklijke Vopak N.V. -

MEI Report Template

Black Sea Connectivity and the South Caucasus Dr. Mamuka Tsereteli March 2021 @MEIFrontier • @MiddleEastInst • 1763 N St. NW, Washington D.C. 20036 Frontier Europe Initiative The Middle East Institute (MEI) Frontier Europe Initiative explores interactions between Middle East countries and their Frontier Europe neighbors – the parts of Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the Caucasus which form a frontier between Western Europe, Russia and the Middle East. The program examines the growing energy, trade, security and political relationships with the aim of developing greater understanding of the interplay between these strategically important regions. About the author Dr. Mamuka Tsereteli is a Non-resident Scholar with Frontier Europe Initiative and a Senior Fellow at Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at American Foreign Policy Council, based in Washington, DC. He has more than thirty years’ experience in academia, diplomacy, and business development. His expertise includes economic and energy security in Europe and Eurasia, political and economic risk analysis and mitigation strategies, and business development in the Black Sea-Caspian region. Photo by Vano Shlamov/ AFP via Getty Images Black Sea Connectivity and the South Caucasus There are growing political, security, trade, and economic interests for multiple actors in the Black Sea region. These actors include traditional Black Sea powers Russia and Turkey; Western-oriented young democracies Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Georgia; supra-national actors like the EU and NATO; the global super-power, the United States; the world’s fastest growing economic power, China; resource- rich countries in Central Asia, including Afghanistan; and of course Iran, which has demonstrated limited interest in the Black Sea in the past, but may become more active, as some recent statements and diplomatic efforts suggest following the change of administration in Washington. -

The U.S., Germany, and Nord Stream 2 U.S

PERSPECTIVE Russia poses a strategic challen- ge for both the United States and Germany, having increa- GLOBAL AND REGIONAL ORDER singly resorted to the use of force against its neighbors and of so-called »active measures« against Western democracies. In response, the U.S. and Euro- THE U.S., pe have imposed punitive eco- nomic sanctions on Moscow. GERMANY, AND Germany and the United States differ in their approaches to Rus- NORD STREAM 2 sia’s energy trade with Europe, giving rise to a potential stum- bling block over Nord Stream 2, an undersea natural gas pipeline between Russia and Germany that is now nearly complete. Matthew Rojansky December 2020 Threatened U.S. sanctions on entities involved in completion of the pipeline project have provoked strong opposition, even as opinion within Germany and Europe is divided over NS2. Both sides hope for resolution of this impasse with the arri val of a new U.S. administra - tion in 2021. GLOBAL AND REGIONAL ORDER THE U.S., GERMANY, AND NORD STREAM 2 U.S. Russia Policy For over half a century, Europe has imported natural gas Any hopes that the shared challenge of the COVID-19 pan- from the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation. This rela- demic in 2020 would bring an easing of these tensions were tionship of mutual dependency in the energy sphere has re- dashed with the outbreak of protests and violence in Bela- mained largely stable, despite tumultuous episodes in polit- rus and full-scale fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan, ical relations between East and West from the Cold War to as well as the attempted murder of opposition leader Alex- the present. -

Gazprom's “Pipeline Policy” in the Black Sea Region

Image Source: https://www.offshoreenergytoday.com/gazprom-turkstream-pipeline-installation- completed-ahead-of-schedule/ Gazprom’s “Pipeline Policy” in the Black Sea Region By Greta K. Wagner Student, University of Glasgow, Intern, The European Geopolitical Forum The Black Sea is often described as a strategic crossroads, which links east-west and north-south transport corridors. Particularly with regard to hydrocarbon resources, the Black Sea serves as a transit route between suppliers in Russia, the Caspian region, Central Asia and the Middle East and consumers in the European Union. Given its strategic importance, the Black Sea is an important puzzle piece for Russia’s “energy superpower” strategy. The Russian energy giant Gazprom has long been the spearhead of the Kremlin’s geopolitical ambitions on the international stage. In the Black Sea region, Gazprom’s “pipeline policy” pursues the triple objective of maintaining Russia’s leading role in the European energy markets, bypassing “uncooperative” transit countries, and expanding Moscow’s geopolitical reach in the neighborhood. Gazprom’s European Strategy Gazprom’s activities in the Black Sea region are part of the company’s pan-European strategy. As the European Union is seeking to diversify its energy supplies and liquefied natural gas (LNG) is increasingly competing with pipeline gas, Gazprom is under pressure to safeguard its commercial interests in Europe. To this end, Gazprom has been striving to reconfigure transport routes to Europe, by reducing the number of transit countries and establishing direct links to key markets such as Germany. The most prominent example of this strategy is the Nord Stream project, which connects the Russian city of Vyborg to the German city of Greifswald via offshore pipeline in the Baltic Sea, thus bypassing the traditional transit routes that run through Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, Czechia, and Slovakia.