Highway Rail Grade Crossing Collision Near Sycamore, South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classic Trains' 2014-2015 Index

INDEX TO VOLUMES 15 and 16 All contents of publications indexed © 2013, 2014, and 2015 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Waukesha, Wis. CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2014 through Winter 2015 (8 issues) ALL ABOARD! (1 issue) 876 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are commonly identified; if there is no common identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country name. ABBREVIATIONS: Sp = Spring Classic Trains, Su = Summer Classic Trains, Fa = Fall Classic Trains, Wi = Winter Classic Trains; AA! = All Aboard!; 14 = 2014, 15 = 2015. Albany & Northern: Strange Bedfellows, Wi14 32 A Bridgeboro Boogie, Fa15 60 21st Century Pullman, Classics Today, Su15 76 Abbey, Wallace W., obituary, Su14 9 Alco: Variety in the Valley, Sp14 68 About the BL2, Fa15 35 Catching the Sales Pitchers, Wi15 38 Amtrak’s GG1 That Might Have Been, Su15 28 Adams, Stuart: Finding FAs, Sp14 20 Anderson, Barry: Article by: Alexandria Steam Show, Fa14 36 Article by: Once Upon a Railway, Sp14 32 Algoma Central: Herding the Goats, Wi15 72 Biographical sketch, Sp14 6 Through the Wilderness on an RDC, AA! 50 Biographical sketch, Wi15 6 Adventures With SP Train 51, AA! 98 Tracks of the Black Bear, Fallen Flags Remembered, Wi14 16 Anderson, Richard J. -

HO-Scale #562 in HO-Scale – Page 35 by Thomas Lange Page 35

st 1 Quarter 2021 Volume 11 Number 1 _____________________________ On the Cover of This Issue Table Of Contents Thomas Lange Models a NYC Des-3 Modeling A NYC DES-3 in HO-Scale #562 In HO-Scale – Page 35 By Thomas Lange Page 35 Modeling The Glass Train By Dave J. Ross Page 39 A Small Midwestern Town Along A NYC Branchline By Chuck Beargie Page 44 Upgrading A Walthers Mainline Observation Car Rich Stoving Shares Photos Of His By John Fiscella Page 52 Modeling - Page 78 From Metal to Paper – Blending Buildings on the Water Level Route By Bob Shaw Page 63 Upgrading A Bowser HO-Scale K-11 By Doug Kisala Page70 Kitbashing NYCS Lots 757-S & 766-S Stockcars By Dave Mackay Page 85 Modeling NYC “Bracket Post” Signals in HO-Scale By Steve Lasher Page 89 Celebrating 50 Years as the Primer Railroad Historical Society NYCentral Modeler From the Cab 5 Extra Board 8 What’s New 17 The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information NYCSHS RPO 23 about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue NYCSHS Models 78 features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related Observation Car 100 models and layouts. The objective of the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. [email protected] NYCentral Modeler 1st Qtr. 2021 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. -

National Transportation Safety Board Investigative Hearing

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 06/15/2018 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2018-12846, and on FDsys.gov BILLING CODE: 7533-01-P National Transportation Safety Board Investigative Hearing Two recent Amtrak (National Railroad Passenger Corporation) accidents have motivated this investigative hearing: first, an Amtrak overspeed derailment in a 30 mph curve that occurred in DuPont, Washington, and, second, an Amtrak head-on collision with a standing freight train in Cayce, South Carolina. The first accident occurred on December 18, 2017, at 7:33 a.m., Pacific standard time, and involved southbound Amtrak passenger train 501, consisting of a leading and trailing locomotive, a power car, 10 passenger railcars, and a luggage car. Train 501 was traveling at 78 mph when it derailed from a highway overpass near DuPont, Washington. The train was on its first regular passenger service trip on a single main track (Lakewood subdivision) at milepost (MP) 19.86. The lead locomotive, the power car, and two passenger railcars derailed onto Interstate 5. Fourteen highway vehicles came into contact with the derailed equipment. At the time of the accident, 77 passengers, 5 Amtrak employees, and a Talgo Incorporated technician were on the train.1 Of these individuals, 3 passengers were killed and 62 passengers and crewmembers were injured. Eight individuals in highway vehicles were also injured. The damage is estimated to be more than $40 million. At the time of the accident, the temperature was 48°F, the wind was from the south at 9 mph, and the visibility was 10 miles in light rain. -

Description of the Niagara Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE NIAGARA QUADRANGLE. By E. M. Kindle and F. B. Taylor.a INTRODUCTION. different altitudes, but as a whole it is distinctly higher than by broad valleys opening northwestward. Across northwestern GENERAL RELATIONS. the surrounding areas and is in general bounded by well-marked Pennsylvania and southwestern New York it is abrupt and escarpments. i nearly straight and its crest is about 1000 feet higher than, and The Niagara quadrangle lies between parallels 43° and 43° In the region of the lower Great Lakes the Glaciated Plains 4 or 5 miles back from the narrow plain bordering Lake Erie. 30' and meridians 78° 30' and 79° and includes the Wilson, province is divided into the Erie, Huron, and Ontario plains From Cattaraugus Creek eastward the scarp is rather less Olcott, Tonawanda, and Lockport 15-minute quadrangles. It and the Laurentian Plateau. (See fig. 2.) The Erie plain abrupt, though higher, and is broken by deep, narrow valleys thus covers one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's sur extending well back into the plateau, so that it appears as a line face, an area, in that latitude, of 870.9 square miles, of which of northward-facing steep-sided promontories jutting out into approximately the northern third, or about 293 square miles, the Erie plain. East of Auburn it merges into the Onondaga lies in Lake Ontario. The map of the Niagara quadrangle shows escarpment. also along its west side a strip from 3 to 6 miles wide comprising The Erie plain extends along the base of the Portage escarp Niagara River and a small area in Canada. -

I for Off Season Travel

Vol. 5, No. 2 February 15, 1978 Bargain Excursion Fares Offered I For Off Season Travel Amtrak is offering bargain fares on tickets are 33 per cent off regular Harrisburg through Pittsburgh to all 21 routes beginning January 31, with round-trip coach fares and may be us other stations on both routes. Harris savings up to 46 per cent off regular ed within 32 days of the first travel burg fares apply to points west only. fares. Still other excursion fares go date. Night Owl fares will not apply Silver Meteor, Silver Star and Pal into effect February 10. from February 17-20 or March 18-26. metto - Round-trip coach excursion The excursion fares, most of which Broadway Limited and National fares already in effect for New York apply only to round-trip coach travel, Limited - Passengers on both routes Florida and Baltimore/Washington are intended to boost ridership during may take advantage of a seven-day Florida passengers will remain in ef the late winter and spring months, round-trip coach excursion fare for fect until October 29. Passengers usually a light travel period. only $5 more than the one-way fare. from New York to any Florida So me of the fares are new while The excursion fare applies between destination pay only $109 for a others are extensions of fares already end point cities, and stations from round-trip coach ticket, while pas- in effect, or rein statements of fares which expired last November. Most of the discounted fares are not of Gareliek Named Executive Vice President fered during holiday periods such as the Washington's Birthday or Easter Martin Garelick, vi ce president of with traditional railroad organiza weekends. -

May Santa Fe's Chief Bring You and Your Family Love and Hope at This

DECEMBER 21, 2020 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 40 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 12 May Santa Fe’s Chief bring you and your family Love and Hope at this time of celebration and in the New Year! 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough 24 Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..……………….… Savery Moore Club Photographer………………………….…. Joe Dumas Guest Contributor……………………………… Paul Beck The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2020 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 40 ■■■■■ NUMBER 12 ■■■■■ DECEMBER 2020 CLUB OFFICERS President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson BILL OF LADING Treasurer………………....Will Baker Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner ...... ……. … .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Contests ................ …............3 Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’22) ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘22) Editor’s Notes. …...........…..10 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’21) Form 19 Calendar…………..3 …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘21) Members ............... …….......11 Memories .............. ………....3 ON THE COVER: Santa Fe’s Chief storms up Potpourri .............. -

Amtrak Passenger Train 501 Derailment Dupont, Washington December 18, 2017

Amtrak Passenger Train 501 Derailment DuPont, Washington December 18, 2017 Accident Report NTSB/RAR-19/01 PB2019-100807 National Transportation Safety Board NTSB/RAR-19/01 PB2019-100807 Notation 58913 Report Date: May 21, 2019 Railroad Accident Report Amtrak Passenger Train 501 Derailment DuPont, Washington December 18, 2017 National Transportation Safety Board 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2019. Amtrak Passenger Train 501 Derailment, DuPont, Washington, December 18, 2017. NTSB/RAR-19/01. Washington, DC. Abstract: On December 18, 2017, at 7:34 a.m. Pacific standard time, southbound Amtrak (National Railroad Passenger Corporation) passenger train 501, consisting of 10 passenger railcars, a power railcar, a baggage railcar, and a locomotive at either end, derailed from a bridge near DuPont, Washington. When the train derailed, it was on its first revenue service run on a single main track (Lakewood Subdivision) at milepost 19.86. There was one run for special guests the week before the accident. Several passenger railcars fell onto Interstate 5 and hit multiple highway vehicles. At the time of the accident, 77 passengers, 5 Amtrak employees, and a Talgo, Inc., technician were on the train. Of these individuals, 3 passengers were killed, and 57 passengers and crewmembers were injured. Additionally, 8 individuals in highway vehicles were injured. The damage is estimated to be more than $25.8 million. The accident investigation focused on the following issues: individual agency responsibilities in preparation for inaugural service, multiagency participation in preparation for inaugural service, Amtrak safety on a host railroad, implementation of positive train control, training and qualifying operating crews, crashworthiness of the Talgo equipment, survival factors and emergency design of equipment, and multiagency emergency response. -

Passenger Timetable Weer 31,1005 Passenger Timetable Hiner 31,1905

passenger timetable Weer 31,1005 passenger timetable Hiner 31,1905 ' 161111'10'11BI ifillitilf"31111111 • .•:: 1...••••••-• Syracuse Utica aoloals 111•44 ALBANY DETROIT Kalamazoo Schenectady Springfield aeons gun BOSTON Erie Poughkeepsie Worcester CHICAGO South Bend CLEVELANI NEW YORK Indianapolis Anderson 00001, Columbus 00111.1.11Terre Haute Dayton mattoon ST. LOUIS CINCINNATI Enjoy allall of the comforts of Central's SLEEPERCOACHES Only $7.00 plus low coach fare! A private room by day.. .a bedroom by nigh' SOME TYPICAL ECONOMY Sleepercoaches combine comfort and economy for SLEEPERCOACH FARES your travel convenience. For business or for family travel, (Include one-way coach fare and Sleepercoaches offer all of these important features. single room charge) • Pay only low coach fare plus modest flat room charge ($7.00 single, $12.60 double) Boston to Chicago $54.85 • Privacy and comfort New York to Detroit $39.54 • Dining and Lounge car service New York to Chicago $49.16 • Central's money-saving Family Fare Plan Cleveland to New York $33.96 , All-weather schedules Next time you plan a trip, be sure to ask your • Single or double rooms New York Central ticket agent or your travel agent • Washstand and toilet in every room for full details on Sleepercoach service available • Special infant accommodations locally. Sleepercoaches now serve New York, • Reduced fares for round hips Chicago, Boston, Rochester, Buffalo, Erie, • To and from the West Cleveland, Toledo, Springfield (Mass.), and Detroit. (371). NEW seo CrI,ITWAL. GOING SOMEWHERE? CHECK YOUR TIMETABLE! Your New York Central timetable has the travel tips to make your trip easier—and more fun, too. -

INDEX to VOLUMES 17 and 18

INDEX TO VOLUMES 17 and 18 CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2016 through Winter 2017 (8 issues) 768 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article usually are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are commonly identified; if there is no common identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country name. ABBREVIATIONS: Sp = Spring Classic Trains, Su = Summer Classic Trains, Fa = Fall Classic Trains, Wi = Winter Classic Trains All contents of publications indexed © 2016, and 2017 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Waukesha, Wis. Milwaukee’s Lost Lakefront Landmark (C&NW), Wi16 91 A B PRR’s Giant One-Day Terminal, Su17 107 Santa Fe Outpost With a Future (Escondido, Calif.), Sp16 91 ACF: See American Car & Foundry Baldwin Locomotive Works: Seashore Lines’ Greatest Monument (Atlantic City), Su16 107 Aerial photos: See Bird’s-Eye View Prosperity Special: Symbol of the 1920s, Wi16 32 Burger, Chris: Alcoa Terminal: Baltimore & Ohio: Articles by: Southern Exposure, Fa16 41 B&O Steam Bows Out in Southern Ohio, Sp17 46 Artistic License, Wi17 -

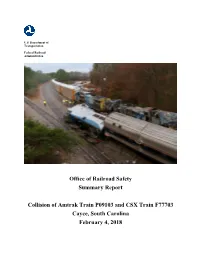

Office of Railroad Safety Summary Report Collision of Amtrak Train

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Summary Report Collision of Amtrak Train P09103 and CSX Train F77703 Cayce, South Carolina February 4, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On Sunday, February 4, 2018, at 2:27 a.m., EST1, stationary CSX Transportation (CSX) freight train F77703 (Train 1) was struck by southbound National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) passenger train P09103 (Train 2) in the Silica storage track at Milepost (MP) S 367.1. The accident occurred on the CSX Columbia Subdivision in Dixiana, South Carolina2. Dixiana is an unincorporated community south of Cayce, South Carolina, in Lexington County. Train 2 encountered a misaligned switch at MP S 366.9 while traveling 57 mph. Train 2 was directed into the Silica storage track where Train 1 was parked, and struck Train 1 at a recorded 50 mph. The Engineer and Conductor of Train 1 were killed in the collision. The Assistant Conductor, 6 on-board Passenger Service Attendants, 122 passengers on Train 1, and the Conductor of Train 2 were also injured. Estimated damages to track and equipment in the accident was $17,336,899. The normal method of operation on the Columbia Subdivision is a Traffic Control System (TCS), which utilizes color light signals to authorize movement in both directions. On the day of the accident, CSX was in the middle of a three-day signal suspension for signal system upgrades. An active signal system would have likely prevented Train 2 from entering the block where the switch was misaligned. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) investigation determined the probable cause of the accident was the crew of Train 1 leaving the switch at MP S 366.9 improperly lined for the storage track. -

Trains in the Adirondacks

Environmental Impact of Trains in the Adirondacks Item Type Other Authors Busch, Ali; Varin, Zoey Download date 29/09/2021 20:57:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/899 Allison Busch and Zoey Varin Trains in the Adirondacks- an Environmental Timeline. Early 1800s- Clinton County’s main mode of transportation and shipping was by steam boat, saw mills usually close to the water for easy transport of goods. 1833- Earliest account of “The Great Ausable Railroad Company.” 1852 to 1868 – Railroad line is built connecting Montreal to Plattsburgh. Mid 1800s- D&H railroad burrows 439 foot tunnel under fort Ticonderoga 1868 to 1875 – railroad built connecting Plattsburgh to Ausable River Station 1874- 40 mile run from Whitehall to port henry opens 1875 to 1878 – railroad connecting “Plattsburgh Junction” to mainline D&H(Delaware & Hudson) to Port Henry 1875-1st train in Plattsburgh 1878- NYS o A few weeks after the first train entered Plattsburgh a train filled with first time riders hits and kills a cow (press republican) o Trains Run on coal . Coal is imported from Virginia coal mines. 1878 – Railroad connecting Plattsburgh and Dannemora is built. This railroad was used to transport prisoners, as well as fuel and supplies, to Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora 1878 to 1894 – railroad built connecting “Chateaugay Junction” to Chateaugay RR. 1880- lumber companies have exhausted the supply of large pines and spruce trees located near bodies of water for easy transport. Allison Busch and Zoey Varin o Lumber companies were able to utilize the trains to transport their goods and were not restricted to staying by large bodies of water. -

HQ-2018-1250 Final.Pdf

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Accident and Analysis Branch Accident Investigation Report HQ-2018-1250 Amtrak P09103 Collision Cayce, South Carolina February 4, 2018 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report, including this one, made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. U.S. Department of Transportation FRA File #HQ-2018-1250 Federal Railroad Administration FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT SYNOPSIS On February 4, 2018, at 2:27 a.m., EST, CSX Transportation (CSX) freight train F77703 (Train 1) was struck head-on by southbound National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) passenger train P09103 (Train 2) in the Silica side track at Milepost (MP) S 367.1. The accident occurred on the CSX Columbia Subdivision in Dixiana, South Carolina. Dixiana is an unincorporated community south of Cayce, South Carolina, in Lexington County. A signal suspension was in effect in the accident area for signal system upgrades. The locomotive and six cars in Train 2 were derailed. The Engineer and Conductor of Train 2 were fatally injured. The Assistant Conductor, 6 on-board Passenger Service Attendants, and 122 passengers were injured on Train 2. The Conductor on Train 1 was also injured. Estimated damages to track and equipment involved in the accident was $17,336,899. An active signal system would have likely prevented Train 2 from entering the block where the switch was misaligned. The weather conditions at the time of this collision were cloudy, dark, and 39 °F.