Thesis Itself Are Univocal in Their Argumentations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joop Den Uyl Special in Argus.Pdf

Kok Joop steekt banaan in de fik Pagina 32 Jaargang 1, nummer 20 12 december 2017 Verschijnt tweewekelijks Losse nummers € 3, – Joop den Uyl, staatsman Dertig jaar na zijn dood komt Joop den Uyl tot leven in een speciale uitneembare bijlage. Socialist die de utopie niet kon missen. De constante in zijn politieke denken. Maar ook: de grootvader, de wanhopige, de ontroerende, de rechtlijnige, de lompe, de onbevangen figuur. Minister Bram Stemerdink over Joops afschuwelijkste momenten. Fotografen kiezen hun meest l e z veelzeggende plaat. t n e De gesneefde biograaf doet een boekje m t open. En nog veel meer. n e c n i v De volgende Argus verschijnt op 9 januari. o t o Vandaar dit extra dikke nummer. f 2017, alvast een terugblik: Rutte misleidt met belasting- voordeel. Leeuwarden koketteert met met beroemdheden die hun heil elders zochten. Oudere werknemers vertrouwen de zaak niet meer. Pagina 2-4 Belastingdeal Verkeerde onderzoekers vonden niks. Pagina 5 Zimbabwe: Wat Sally deed, liet Grace na. Pagina 6 Cyaankali Toneelstukje Praljak houdt conflict levend. Pagina 7 Philipp Blom Gaan! Alarm waar geen speld De niet te missen film. De tussen te krijgen is. overtuigende expo. Het Pagina 28 meest kersterige concert. Het verrassende boek. Word abonnee: Voortaan: Argus-tips. www.argusvrienden.nl Pagina 29 2017 12 december 2017 / 2 12 december 2017 / 3 Zes vaste medewerkers van Argus’ De dode mus van Rutte III binnenlandpagina’s kregen de Think global, vraag: Wat vind jij het meest door FLIP DE KAM hele begrotingsoverschot uit het act local basispad te ‘verjubelen’. opmerkelijke van 2017? et is domweg onmogelijk op het basispad stijgen de col - door NICO HAASBROEK donut - één gebeurtenis te noemen lectieve lasten in de komende kabi - model for - Hdie economie en over - netsperiode met vijf miljard euro. -

Ford, Kissinger, NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns, NATO

File scanned from the National Security Adviser's Memoranda of Conversation Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 0 MEMoRANDUM • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON ~/NODIS MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: NATO Secretary General Joseph Luns NATO Deputy Secretary General Pansa Cedronio Assistant Secretary General for Defense Planning and Policy Colin Hum.phreys Am.bassador Andre de Staercke, Belgium. Ambassador Arthur Menzies, Canada Am.bassador Ankar Svart, Denm.ark Am.bassador Francois de Rose, France Am.bassador Franz Krapf, Germ.any Am.bassador Byron Theodoropoulos, Greece Am.bassador Tom.as Tom.asson, Iceland Am.bassador Felice Catalano, Italy Am.bassador Marcel Fischback, Luxem.bourg Am.bassador A. K. F. (Karel) Hartogh, Netherlands Am.bassador Rolf Busch, Norway Am.bassador Joao de Freitas Cruz, Portugal Am.bas sador Orhan Eralp, Turkey Am.bassador Sir Edward Peck, United Kingdom. Am.bassador David K. E. Bruce, United States The President Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State Jam.es R. Schlesinger, Secretary of Defense Donald Rum.sfeld, Assistant to the President Brent Scowcroft, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Mfairs Robert Goldwin, Special Consultant to the President H. Allan Holm.es, Director, Office of NATO and Atlantic Political-Military Mfairs, Departm.ent of State A. Denis Clift~ Staff Mem.ber, National Security Council~ DATE AND TIME: June 19, 1975 4:05 - 5:02 p. m.. PLACE: The Cabinet Room. The White House ~/NODIS s-ECR:g:rI NODIS - z SUBJECT: President's Meeting with Permanent Representatives to the North Atlantic Council President: (Having gone around the table to greet each participant individually) Won't you all please sit down. -

1 WITTEVEEN, Hendrikus Johannes (Known As Johan Or Johannes), Dutch Politician and Fifth Managing Director of the International

1 WITTEVEEN, Hendrikus Johannes (known as Johan or Johannes), Dutch politician and fifth Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) 1973-1978, was born 12 June 1921 in Den Dolder and passed away 23 April 2019 in Wassenaar, the Netherlands. He was the son of Willem Gerrit Witteveen, civil engineer and Rotterdam city planner, and Anna Maria Wibaut, leader of a local Sufi centre. On 3 March 1949 he married Liesbeth Ratan de Vries Feijens, piano teacher, with whom he had one daughter and three sons. Source: www.imf.org/external/np/exr/chron/mds.asp Witteveen spent most of his youth in Rotterdam, where his father worked as director of the new office for city planning. His mother was the daughter of a prominent Social-Democrat couple, Floor Wibaut and Mathilde Wibaut-Berdenis van Berlekom, but politically Witteveen’s parents were Liberal. His mother was actively involved in the Dutch Sufi movement, inspired by Inayat Khan, the teacher of Universal Sufism. Sufism emphasizes establishing harmonious human relations through its focus on themes such as love, harmony and beauty. Witteveen felt attracted to Sufism, which helped him to become a more balanced young person. At the age of 18 the leader of the Rotterdam Sufi Centre formally initiated him, which led to his lifelong commitment to, and study of, the Sufi message. After attending public grammar school, the Gymnasium Erasmianum, Witteveen studied economics at the Netherlands School of Economics between 1939 and 1946. The aerial bombardment of Rotterdam by the German air force in May 1940 destroyed the city centre and marked the beginning of the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany. -

De Parallelle Levens Van Hans En Hans

De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans Door Roelof Bouwman - 16 januari 2021 Geplaatst in Boeken Het is nog maar nauwelijks voorstelbaar, maar tot ver in de jaren negentig van de vorige eeuw verschenen in Nederland nauwelijks biografieën. Terwijl je in Britse, Amerikaanse, Duitse en Franse boekwinkels struikelde over de vuistdikke levensbeschrijvingen van historische kopstukken als Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Konrad Adenauer en Charles de Gaulle, hadden Nederlandse historici nauwelijks belangstelling voor het biografische genre. Over de meeste grote vaderlanders – van Johan Rudolf Thorbecke tot Multatuli, van Anton Philips tot Aletta Jacobs en van koningin Wilhelmina tot Joseph Luns – bestond geen enkel fatsoenlijk boek. Het verloop van de geschiedenis, zo hoorde je Nederlandse historici vaak beweren, wordt niet bepaald door personen, maar door processen: industrialisatie, (de)kolonisatie, verzuiling, democratisering, emancipatie, enzovoorts. Daarnaast werd de weerzin tegen biografieën gevoed door de protestantse angst – in Nederland wijdverbreid – voor het ‘ophemelen’ van individuen. Van feministische zijde kwam daar nog de afkeer bij tegen geschiedschrijving met ‘grote mannen’ in de hoofdrol. Al met al een dodelijke cocktail. Maar nu: een tsunami van biografieën Inmiddels is alles anders. Het anti-biografische klimaat is de afgelopen vijfentwintig jaar dermate drastisch omgeslagen dat het bijvoorbeeld moeilijk is geworden om een prominente, twintigste-eeuwse Wynia's week: De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans | 1 De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans politicus te noemen wiens leven nog níet is geboekstaafd. De oud-premiers Abraham Kuyper, Dirk Jan de Geer en Joop den Uyl maar ook VVD-boegbeeld Neelie Kroes en D66-prominent Hans Gruijters kregen zelfs twee keer een biografie. -

Rondom De Nacht Van Schmelzer Parlementaire Geschiedenis Van Nederland Na 1945

Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945 Deel 1, Het kabinet-Schermerhorn-Drees 24 juni 1945 – 3 juli 1946 door F.J.F.M. Duynstee en J. Bosmans Deel 2, De periode van het kabinet-Beel 3 juli 1946 – 7 augustus 1948 door M.D. Bogaarts Deel 3, Het kabinet-Drees-Van Schaik 7 augustus 1948 – 15 maart 1951 onder redactie van P.F. Maas en J.M.M.J. Clerx Deel 4, Het kabinet-Drees II 1951 – 1952 onder redactie van J.J.M. Ramakers Deel 5, Het kabinet-Drees III 1952 – 1956 onder redactie van Carla van Baalen en Jan Ramakers Deel 6, Het kabinet-Drees IV en het kabinet-Beel II 1956 – 1959 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Peter van der Heiden Deel 7,Hetkabinet-DeQuay 1959 – 1963 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Jan Ramakers Deel 8, De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963 – 1967 onder redactie van Peter van der Heiden en Alexander van Kessel Stichting Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Den Haag Stichting Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945, Deel 8 Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963-1967 PETER VAN DER HEIDEN EN ALEXANDER VAN KESSEL (RED.) Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis Auteurs: Anne Bos Charlotte Brand Jan Willem Brouwer Peter van Griensven PetervanderHeiden Alexander van Kessel Marij Leenders Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Hilde Reiding Met medewerking van: Mirjam Adriaanse Miel Jacobs Teun Verberne Jonn van Zuthem Boom – Amsterdam Afbeelding omslag: Cals verlaat de Tweede Kamer na de val van zijn kabinet in de nacht van 13 op 14 oktober 1966.[anp] Omslagontwerp: Mesika Design, Hilversum Zetwerk: Velotekst (B.L. -

Bezinning Op Het Buitenland

Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) Bezinning op het buitenland Het Nederlands buitenlands beleid Zijn de traditionele ijkpunten van het naoorlogse Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid in een onzekere wereld nog up to date? In hoeverre kan het bestaande buitenlandse beleid van Nederland nog gebaseerd worden op de traditionele consensus rond de drie beginselen van (1) trans-Atlantisch veiligheidsbeleid, (2) Europese economische integratie volgens de communautaire methode, en (3) ijveren voor versterking van de internationale (rechts)orde en haar multilaterale instellingen? Is er sprake van een teloorgang van die consensus en verwarring over de nieuwe werkelijkheid? Recente internationale ontwikkelingen op veiligheidspolitiek, economisch, financieel, monetair en institutioneel terrein, als mede op het gebied van mensenrechten en Duco Hellema, Mathieu Segers en Jan Rood (red.) ontwikkelingssamenwerking, dagen uit tot een herbezinning op de kernwaarden en uitgangspunten van het Nederlandse buitenlandse beleid. Het lijkt daarbij urgent een dergelijke herbezinning nu eens niet louter ‘van buiten naar binnen’, maar ook andersom vorm te geven. Het gaat derhalve niet alleen om de vraag wat de veranderingen in de wereld voor gevolgen (moeten) hebben voor het Nederlandse buitenlands beleid. Ook dient nagegaan te worden in hoeverre de Nederlandse perceptie van de eigen rol in de internationale politiek (nog) adequaat is. In verlengde hiervan zijn meer historische vragen te stellen. In hoeverre is daadwerkelijk sprake van constanten in het -

Frits Bolkestein Is Een Leergierig Ventje Van Veertien Jaar En

1 HET BEGIN: 1948-1963 rits Bolkestein is een leergierig ventje van veertien jaar en zit in de tweede klas van het prestigieuze Barlaeus Gymnasium Fin Amsterdam, Neelie Kroes speelt in Rotterdam op de kleu terschool, niet met poppen maar met houten vrachtautootjes, en ook Hans Wiegel vermaakt zich nog in de zandbak, terwijl Ed Nijpels nog geboren moet worden. Terwijl deze kinderen nog geen flauwe notie hebben van de roem die zij later in politiek en bestuur zullen vergaren, loopt de 21-jarige Schilleman Overwa ter het Amsterdamse Centraal Station uit. Het is zaterdag 24 ja nuari 1948. De snijdende en harde oostenwind maakt het met een paar graden boven nul onaangenaam koud. Gevoelstemperatuur min vijf, zouden we nu zeggen. De jongeman uit het Zuid-Hol- landse dorpje Strijen trekt zijn kraag hoog op, steekt zijn handen diep in zijn jaszakken en loopt naar de halte van lijn 1. De tram staat gelukkig al klaar en negen haltes verder stapt hij uit op het Leidseplein. Overwater heeft van tevoren goed geïnformeerd hoe hij bij Theater Bellevue moet komen; hij kent de hoofdstad niet. Het is gaan sneeuwen, grote, natte vlokken, en dat zal nog uren zo doorgaan. Gelukkig hoeft hij niet ver te lopen. Hij wandelt langs hotel-restaurant Americain, slaat rechts af de Leidselcade op en betreedt even later het zalencomplex waar ruim twaalf jaar eerder Max Euwe wereldkampioen schaken is geworden tegen de Rus Aljechin. 9 Een week daarvoor is O ver water voor het eerst van zijn leven in Amsterdam. Zijn Partij van de Vrijheid (PvdV) heeft er ver gaderd over samenwerking met het Comité-Oud. -

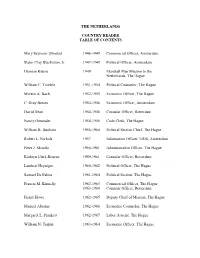

The Netherlands Country Reader Table of Contents

THE NETHERLANDS COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mary Seymour Olmsted 1946-1949 Commercial Officer, Amsterdam Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 194 -1949 Political Officer, Amsterdam Herman Kleine 1949 Marshall Plan Mission to the Netherlands, The Hague (illiam C. Trimble 1951-1954 Political Counselor, The Hague Morton A. Bach 1952-1955 ,conomic Officer, The Hague C. -ray Bream 1954-1956 ,conomic Officer, Amsterdam .avid .ean 1954-1956 Consular Officer, 0otterdam Nancy Ostrander 1954-1956 Code Clerk, The Hague (illiam B. .unham 1956-1961 Political Section Chief, The Hague 0obert 2. Nichols 195 Information Officer, 4SIS, Amsterdam Peter J. Skoufis 1958-1961 Administrative Officer, The Hague Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1959-1961 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 2ambert Heyniger 1961-1962 Political Officer, The Hague Samuel .e Palma 1961-1964 Political Section, The Hague 6rancis M. Kinnelly 1962-1963 Commercial Officer, The Hague 1963-1964 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 6isher Ho8e 1962-1965 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Manuel Abrams 1962-1966 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Margaret 2. Plunkett 1962-196 2abor Attach:, The Hague (illiam N. Turpin 1963-1964 ,conomic Officer, The Hague .onald 0. Norland 1964-1969 Political Officer, The Hague ,mmerson M. Bro8n 1966-19 1 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Thomas J. .unnigan 1969-19 2 Political Counselor, The Hague J. (illiam Middendorf, II 1969-19 3 Ambassador, Netherlands ,lden B. ,rickson 19 1-19 4 Consul -eneral, 0otterdam ,ugene M. Braderman 19 1-19 4 Political Officer, Amsterdam 0ay ,. Jones 19 1-19 2 Secretary, The Hague (ayne 2eininger 19 4-19 6 Consular / Administrative Officer, 0otterdam Martin Van Heuven 1932-194 Childhood, 4trecht 19 5-19 8 Political Counselor, The Hague ,lizabeth Ann Bro8n 19 5-19 9 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Victor 2. -

Economic Structuralism Examined, a Case Study

Economic Structuralism Examined, a Case Study: Interest Groups and Dutch European Policy in the Fifties Bachelor Thesis of: Stefan Bekedam Student number: 3378438 22 June 2011 Supervisor: Mathieu Segers STATEMENT OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 4 1.1 FOREIGN POLICY AND ECONOMICS. ...................................................................... 5 1.2 STRUCTURE AND HYPOTHESIS ................................................................................ 6 1.3 METHOD ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 EPISTEMOLOGICAL QUESTIONS .............................................................................. 7 1.5 SETTING THE SCENE ................................................................................................... 9 1.6 BENELUX...................................................................................................................... 11 2. COAL AND STEEL ....................................................................................... 14 2.1 THE LAUNCH OF THE SCHUMAN PLAN ............................................................... 14 2.2 DUTCH REACTION ..................................................................................................... 14 2.3 ECONOMIC DIFFICULTIES ....................................................................................... 16 2.4 THE STIKKER PLAN .................................................................................................. -

US Authorities 2360. Note for the File on Meeting of the Secretary

US authorities 2360. Note for the file on meeting of the Secretary General with the United States Secretary of State Rogers on 9 December 1971 during the Ministerial meeting ( 9 December 1971) ENG 2361. Memorandum for the file by Secretary General Luns on a meeting with President Nixon on 31 January 1972 (5 February 1972) ENG 1610. United States Permanent Representative on the North Atlantic Council. Letters by President Nixon and Secretary of State W. Rogers to Secretary General Joseph Luns on Nixon’s visits to China and USSR (14 March 1972) ENG 1660. Various correspondences between US Permanent Representative to NATO and later Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld and Secretary General Luns (1973- 1980) ENG 2367. Memorandum for the file by Director of Secretary General’s Private Office Mr. Van Campen on visit of the Secretary General to the United States on 11-14 April 1973 and his meetings with Secretary of the Treasury Mr. Shultz, Secretary of State Mr. Rogers and Secretary of Defence Mr. Richardson (April 1973) ENG 2369-1. Memorandum for the file by Director of Secretary General’s Private Office Mr. Van Campen on visit of the Secretary General to Canada and the United States 7-14 April 1973 and his meeting with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (16 April 1973) ENG 2368-1. Memorandum for the file by Secretary General Luns on his meeting with President Nixon of 12 April 1973 (17 April 1973) ENG 2369-2. Memorandum for the file by Secretary General Luns on his meeting with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger on 9 June 1973 (9 June 1973) ENG 2368-2. -

Tracing the Treaties of the EU (March 2012)

A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon — Tracing the treaties of the EU (March 2012) Caption: This brochure, produced by the General Secretariat of the Council and published in March 2012, looks back at the history of European integration through the treaties, from the Treaty of Paris to the Treaty of Lisbon. Source: General Secretariat of the Council. A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon – Tracing the treaties of the European Union. Publications Offi ce of the European Union. Luxembourg: March 2012. 55 p. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/librairie/PDF/QC3111407ENC.pdf. Copyright: (c) European Union, 1995-2013 URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/a_union_of_law_from_paris_to_lisbon_tracing_the_treaties_of_the_eu_march_2012-en- 45502554-e5ee-4b34-9043-d52811d422ed.html Publication date: 18/12/2013 1 / 61 18/12/2013 CONSILIUM EN A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon Tracing the treaties of the European Union GENERAL SECRETARIAT COUNCIL THE OF 1951–2011: 60 YEARS A UNION OF LAW THE EUROPEAN UNION 2010011 9 December 2011 THE TREATIES OF Treaty of Accession of Croatia,ratification in progress 1 December 2009 Lisbon Treaty, 1 January 2007 THE EUROPEAN UNION Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania, Treaty establishing a Constitution29 for October Europe, 2004 signed on did not come into force Lisbon: 13 December 2007 CHRON BOJOTUJUVUJPO $PVODJMCFDPNFT Treaty of Accession of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, t ЅF&VSPQFBO 1 May 2004 CFUXFFOUIF&VSPQFBO Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia, t - BXNBLJOH QBSJUZ -

Persona Non Grata

Persona non grata Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Persona non grata. Papieren Tijger, Breda 1996 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003pers02_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 5 Revenge is a kind of wild justice, which the more man's nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out. Francis Bacon Willem Oltmans, Persona non grata 7 Voorwoord In 1994 ben ik 41 jaar journalist. In dit boek is in een notedop beschreven hoe ik 38 jaar door de overheid en de inlichtingendiensten ben geterroriseerd in opdracht van Joseph Luns, nadat hij ongelijk kreeg in de kwestie Nieuw Guinea, precies zoals ik hem had voorspeld. Al in 1958 vluchtte ik naar de VS waar de achtervolging, zoals geheime documenten in 1991 zouden bewijzen, onverminderd werd voortgezet. Het uiteindelijke doel van mijn vijand was niet alleen om mijn werk als journalist onmogelijk te maken, maar om mij uiteindelijk tot de bedelstaf te brengen. Mijn ouders hadden me voldoende fondsen nagelaten, zodat ik deze ongelijke strijd tot 1990 heb kunnen volhouden. Toen vluchtte ik opnieuw, ditmaal naar Zuid-Afrika, maar ook daar werd de terreur voortgezet. In 1992 ging ik gedwongen naar Amsterdam terug en probeer me in een studio van zes bij zes in de Jordaan staande te houden van een minimumuitkering van 1.240 gulden per maand. Mijn vrienden hebben me sedert jaren geadviseerd me niet langer aan de regels te houden waar de overheid nooit anders heeft gedaan dan mijn rechten als burger en journalist met voeten te treden. Maar dan is er altijd weer de homunculus, het kleine mannetje in mijn brein, door Leibnitz eens omschreven als de demon of de kabouter, die me influistert ‘Doe anderen niet aan wat zij jou aandoen’.