Afrin Under Turkish Control: Political, Economic and Social Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

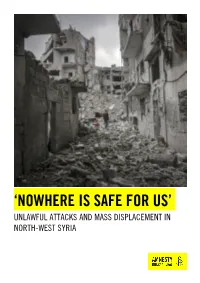

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

45 the RESURRECTION of SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS by Ro

THE RESURRECTION OF SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS By Rodi Hevian* This article examines the current political landscape of the Kurdish region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played in the ongoing Syrian civil war, and intra-Kurdish relations. For many years, the Kurds in Syria were Iraqi Kurdistan to Afrin in the northwest on subjected to discrimination at the hands of the the Turkish border. This article examines the Ba’th regime and were stripped of their basic current political landscape of the Kurdish rights.1 During the 1960s and 1970s, some region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played Syrian Kurds were deprived of citizenship, in the ongoing conflict, and intra-Kurdish leaving them with no legal status in the relations. country.2 Although Syria was a key player in the modern Kurdish struggle against Turkey and Iraq, its policies toward the Kurds there THE KURDS IN SYRIA were in many cases worse than those in the neighboring countries. On the one hand, the It is estimated that there are some 3 million Asad regime provided safe haven for the Kurds in Syria, constituting 13 percent of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syria’s 23 million inhabitants. They mostly Kurdish movements in Iraq fighting Saddam’s occupy the northern part of the country, a regime. On the other hand, it cracked down on region that borders with Iraqi Kurdistan to the its own Kurds in the northern part of the east and Turkey to the north and west. There country. Kurdish parties, Kurdish language, are also some major districts in Aleppo and Kurdish culture and Kurdish names were Damascus that are populated by the Kurds. -

The Syrian Crisis: an Analysis of Neighboring Countries' Stances

POLICY ANALYSIS The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Series: Policy Analysis Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. ____________________________ The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non-Arab researchers. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies PO Box 10277 Street No. 826, Zone 66 Doha, Qatar Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651 www.dohainstitute.org Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Lebanese Position toward the Syrian Revolution 1 Factors behind the Lebanese stances 8 Internationally 14 Domestically 14 The Jordanian Stance 15 Regional and International Influences 18 The Syrian Revolution and the Arab Levant 22 NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES’ STANCES ON SYRIA Introduction The Arab Levant region has significant geopolitical importance in the global political map, particularly because of its diverse ethnic and religious identities and the complexity of its social and political structures. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “Torpedoed” by the West? By Adam Larson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, May 02, 2013 Theme: US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA Since the perplexing conflict in Syria first broke out two years ago, the Western powers’ assistance to the anti-government side has been consistent, but relatively indirect. The Americans and Europeans lay the mental, legal, diplomatic, and financial groundwork for regime change in Syria. Meanwhile, Arab/Muslim allies in Turkey and the Persian Gulf are left with the heavy lifting of directly supporting Syrian rebels, and getting weapons and supplementary fighters in place. The involvement of the United States in particular has been extremely lackluster, at least in comparison to its aggressive stance on a similar crisis in Libya not long ago. Hopes of securing major American and allied force, preferrably a Libya-style “no-fly zone,” always leaned most on U.S. president Obama’s announcement of December 3, 2012, that any use of chemical weapons (CW) by the Assad regime – or perhaps their simple transfer – will cross a “red line.” And that, he implied, would trigger direct U.S. intervention. This was followed by vague allegations by the Syrian opposition – on December 6, 8, and 23 – of government CW attacks. [1] Nothing changed, and the allegations stopped for a while. However, as the war entered its third year in mid-March, 2013, a slew of new allegations came flying in. This started with a March 19 attack on Khan Al-Assal, a contested western district of Aleppo, killing a reported 25-31 people. -

Turkey Orchestrating Violence Beyond Borders

TURKEY: ORCHESTRATING VIOLENCE BEYOND BORDERS By RETHINKING Mohammed Sami POLICY BRIEF Middle East Analyst January 2020 SECURITY IN 2020 SERIES INTRODUCTION KEY TAKEAWAYS In late December 2019, the Tripoli based-UN backed- • Turkey continues its deployment of Government of National Accord (GNA) appealed for Syrian rebels to Libya. Turkey to intervene in Libya. As a response, the Turkish rd Parliament held an emergency session on January 3 , • Syrian rebels are deployed with attractive 2020, and voted to authorize President Recep Tayep Er- salaries to fight in Libya. dogan to deploy Turkish troops to Libya. Soon after, the deployment of troops materialized. However, not only • The selection process of rebels was based were Turkish military forces deployed but Syrian rebels on a specific criterion. from northern Syria too. In recent months, Turkey’s military activities, such as its expatriation of Syrian ref- • Private military contractors played a role in ugees to their war-torn country and the deployment of preparing and deploying Syrian rebels to Turkish-backed Syrian rebels to fight along the GNA in Libya. Libya, pose serious risks of escalation in the region. While the European Union remains committed to fund its Facility for Refugees in Turkey, these activities re- local activists, partners, and local population, this pol- quire greater scrutiny on its financial support provided icy brief explores Turkey’s deployment of Syrian rebels to Turkey. Based on first-hand data collected through to Libya, its deportation of refugees to Syria and ques- interviews conducted by the BIC research team with tions the implications these developments have on the EU’s Facility for Refugees in Turkey. -

Cooperation on Turkey's Transboundary Waters

Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Status Report commissioned by the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety F+E Project No. 903 19 226 Oktober 2005 Imprint Authors: Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Project management: Adelphi Research gGmbH Caspar-Theyß-Straße 14a D – 14193 Berlin Phone: +49-30-8900068-0 Fax: +49-30-8900068-10 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.adelphi-research.de Publisher: The German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety D – 11055 Berlin Phone: +49-01888-305-0 Fax: +49-01888-305 20 44 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bmu.de © Adelphi Research gGmbH and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, 2005 Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters i Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 1.1 Motive and main objectives ........................................................................................1 1.2 Structure of this report................................................................................................3 2 STRATEGIC ROLE OF WATER RESOURCES FOR THE TURKISH ECONOMY..........5 2.1 Climate and water resources......................................................................................5 2.2 Infrastructure development.........................................................................................7 -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

Syria SITREP Map 07

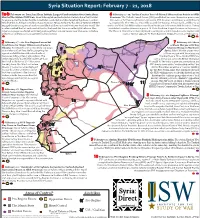

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Download the Information Brochure

INVENTORY OF SHARED WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN ASIA INVENTORY OF SHARED WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN ASIA AbOuT ThE Inventory The Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia is the first effort led by the united Nations to catalogue and characterize transboundary surface and groundwater resources in the Middle East. It is a desk study AbOuT ESCWA by the united Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural The united Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) Resources (bGR), which has been developed in close consultation with is one of the five Regional Commissions of the united Nations Secretariat. It national, regional and international experts. Through the inter-governmental focuses on cross-sectoral approaches for achieving sustainable development Committee on Water Resources and nominated focal points, ESCWA member and integrated natural resources management by informing regional policies, countries have actively participated in the preparation of this Inventory, dialogue and cooperation. ESCWA comprises Arab countries in Western Asia including the identification of shared basins, the compilation of information and North Africa: bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, and the review of chapters. Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the united Arab Emirates and Yemen. The Inventory follows a standardized structure, with 9 surface water chapters and 17 groundwater chapters that systematically address hydrology, hydrogeology, water resources development and use, international water AbOuT bGR agreements and transboundary water management efforts. The chapters cover all rivers and groundwater resources shared between and by Arab bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (bGR) is the German countries in the Middle East.