Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

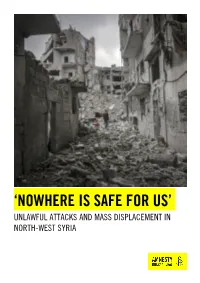

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts. -

The 12Th Annual Report on Human Rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013)

The 12th annual report On human rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013) January 2014 January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Arbitrary detention and Enforced Disappearances 11 Besiegement: slow-motion genocide 14 Violations committed against health and the health sector 17 The conditions of Syrian refugees 23 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 27 Violations committed against freedom of the press 31 Violations committed against houses of worship 39 The targeting of historical and archaeological sites 44 Legal and legislative amendments 46 References 47 About SHRC 48 The 12th annual report on human rights in Syria (January 2013 – December 2013) Introduction The year 2013 witnessed a continuation of grave and unprecedented violations committed against the Syrian people amidst a similarly shocking and unprecedented silence in the international community since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. Throughout the year, massacres were committed on almost a daily basis killing more than 40.000 people and injuring 100.000 others at least. In its attacks, the regime used heavy weapons, small arms, cold weapons and even internationally prohibited weapons. The chemical attack on eastern Ghouta is considered a landmark in the violations committed by the regime against civilians; it is also considered a milestone in the international community’s response to human rights violations Throughout the year, massacres in Syria, despite it not being the first attack in which were committed on almost a daily internationally prohibited weapons have been used by the basis killing more than 40.000 regime. The international community’s response to the crime people and injuring 100.000 drew the international public’s attention to the atrocities others at least. -

CTC Sentinel 6:8 (2013)

AUGUST 2013 . SPECIAL ISSUE . VOL 6 . ISSUE 8 Contents Syria: A Wicked Problem for All By Bryan Price INTRODUCTION 1 Syria: A Wicked Problem for All By Bryan Price SPECIAL REPORTS 4 Turkey’s Tangled Syria Policy By Hugh Pope 9 Israel’s Response to the Crisis in Syria By Arie Perliger 11 Iran’s Unwavering Support to Assad’s Syria By Karim Sadjadpour 14 Hizb Allah’s Gambit in Syria By Matthew Levitt and Aaron Y. Zelin 18 The Battle for Qusayr: How the Syrian Regime and Hizb Allah Tipped the Balance By Nicholas Blanford 23 The Non-State Militant Landscape in Syria By Aron Lund 28 From Karbala to Sayyida Zaynab: Iraqi Fighters in Syria’s Shi`a Militias By Phillip Smyth 32 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Syrian rebels stand guard as protesters wave Islamist flags during an anti-regime demonstration in Aleppo in March 2013. - AFP/Getty n august 26, 2013, Secretary from those that were truly “wicked.”3 In of State John Kerry called their interpretation, wicked problems the recent use of chemical feature innumerable causes, are weapons outside of Damascus tough to adequately describe, and by O“undeniable” and a “moral obscenity.”1 definition have no “right” answers. This is the latest chapter in an already In fact, solutions to wicked problems complex civil war in Syria, a crisis are impossible to objectively evaluate; About the CTC Sentinel that Kerry’s predecessor called a rather, it is better to evaluate solutions The Combating Terrorism Center is an “wicked problem” for the U.S. foreign to these problems as being shades of independent educational and research policy establishment.2 That term good and bad.4 institution based in the Department of Social was introduced 40 years ago by two Sciences at the United States Military Academy, professors of urban planning who were By anyone’s account, the Syrian civil West Point. -

BACKGROUNDER Rebel Groups in Northern Aleppo Province

Jeffrey Bolling BACKGROUNDER August 29, 2012 REBEL GROUps IN NOrthERN ALEppO PROVINCE n August 5, 2012, BBC World News reported over 20,000 Syrian troops massed around Aleppo, Oready to move into rebel-occupied districts of the city in what has become one of the largest military operations of the ongoing Syrian conflict.1 Until recently, rebel activity in Aleppo, Syria’s largest city and primary commercial hub, had been largely overshadowed by clashes elsewhere in the country.2 Despite the overwhelming media attention given to Homs and Damascus, the ongoing showdown between rebel and regime forces in Aleppo City is rooted in the months-old conflict in Aleppo’s northern countryside. The development of the major rebel units of the Kilis Major Hamadeen has kept Corridor, a string of outlying towns that straddle the a low profile, appearing Aleppo-Gaziantep highway connecting Turkey to only to make official northern Syria, sheds light on the current battle for announcements for the Ahrar Aleppo. The armed opposition’s willingness to come al-Shamal Brigade or the together in increasingly large and ambitious unit Aleppo Military Council.4 hierarchies has augmented rebel ability to resist the Hamadeen’s statements Assad regime. Between March and August 2012, Aleppo are devoid of personal rebel groups have resisted major regime offensives and information and ideological MAJOR MOHAMMED HAMADEEN, LEADER OF AHRAR AL-SHAMAL; coordinated large scale counteroffensives in the Kilis affiliation. Unlike rebel SOURCE: YOUTUBE Corridor and al-Bab, a town 40 kilometers east of Aleppo leaders in other parts of Syria, City. These rebel successes have exposed the limits of the whose strong personalities often occupy a central place regime’s ability to project force outside of major urban in the public portrayal of their units’ identities, this low centers. -

The New Salafi Politics October 16, 2012 KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/GETTYIMAGES KHALIL POMEPS Briefings 14 Contents

arab uprisings The New Salafi Politics October 16, 2012 KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/GETTYIMAGES KHALIL POMEPS Briefings 14 Contents A New Salafi Politics . 6 The Salafi Moment . 8 The New Islamists . 10 Democracy, Salafi Style . 14 Who are Tunisia’s Salafis? . 16 Planting the seeds of Tunisia’s Ansar al Sharia . 20 Tunisia’s student Salafis . 22 Jihadists and Post-Jihadists in the Sinai . 25 The battle for al-Azhar . 28 Egypt’s ‘blessed’ Salafi votes . 30 Know your Ansar al-Sharia . 32 Osama bin Laden and the Saudi Muslim Brotherhood . 34 Lebanon’s Salafi Scare . 36 Islamism and the Syrian uprising . 38 The dangerous U .S . double standard on Islamist extremism . 48 The failure of #MuslimRage . 50 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index A new Salafi politics http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2012/10/12/a_new_salafi_politics The Salafi Moment http://www .foreignpolicy .com/articles/2012/09/12/the_salafi_moment The New Islamists http://www .foreignpolicy -

ICT Jihadi Monitoring Group

ICT Jihadi Monitoring Group PERIODIC REVIEW Bimonthly Report Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites The First Half of November 2013 International Institute for Counter Terrorism (ICT) Additional resources are available on the ICT Website: www.ict.org.il Highlights This report summarizes notable events discussed on jihadist Web forums during the first half of November 2013. Following are the main points covered in the report: The killing of Hakimullah-Mehsud, leader of the Taliban-Pakistan, provokes calls from jihadist elements to launch reprisals against the United States. At this stage, it is unclear if his replacement will continue talks with the Pakistani government or increase the organization’s terrorist activities. The rivalry between jihadist groups in Syria continues, including reciprocal killings by each side. Evidence from the arena of jihad in Syria indicates that violence is also being used against civilians. Each group, including opposition forces and Islamic organizations, emphasizes the corruption of the others, sometimes with regard to the West’s support of some of the groups. The Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham threatens to launch reprisals against Kurdish members of secular movements, such as the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), and against Kurdish security and intelligence officials, because of their cooperation with Bashar al-Assad’s regime and their role in the war against terrorism. In addition, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham announces that it is going to launch reprisals against the Badr Martyrs Brigade because of its operations against the mujahideen and Sunni civilians in Syria. The discourse among visitors to jihadist Web forums concerns the current operational strategy of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and Al-Sham, which is to expand an Islamic state by acting against three strategic threats – the Crusaders, the Shi’ites and the secular camp. -

Euphrates Shield Developments in Six Months

February 2017 www.jusoor.co Analytical Report 0 Euphrates Shield Developments in six months Analytical Report Euphrates Shield Developments in six months www.jusoor.co Analytical Report 1 Euphrates Shield Developments in six months www.jusoor.co Analytical Report 2 contents Introduction .................................................................................. 3 First: the course and achievement ............................................... 3 1- Military Theme .................................................................... 3 -The second phase .................................................................. 4 -The third phase ...................................................................... 5 2- The Service Theme .............................................................. 6 1-Health:Turkish health ministry opened the hospital of Jarablus on 25/9/2016 (about a month after the start of Euphrates Shield operation). .................................................. 6 2-Aids and services: ............................................................... 6 3-The infrastructure: ............................................................... 6 4-Education: ........................................................................... 7 5-Security: .............................................................................. 7 Second: Stances and Reactions .................................................... 7 1-Internationa reactions ............................................................ 7 2-Local reactions ..................................................................... -

Militär Utveckling Och Territoriell Kontroll I Syriens 14 Provinser

TEMARAPPORT 2017-01-12, version 1.0 Militär utveckling och territoriell kontroll i Syriens 14 provinser Bakgrundsbilden ska: - vara fri att använda - ha bra/hög upplösning - fylla hela rutan 27 - 04 - L04 2016 L04 Lifos Temarapport: Militär utveckling och territoriell kontroll i Syriens 14 provinser Om rapporten Denna rapport är skriven i enlighet med EU:s allmänna riktlinjer för framtagande av landinformation (2008). Den är en opartisk presentation av tillförlitlig och relevant landinformation avsedd för handläggning av migrationsärenden. Rapporten bygger på noggrant utvalda informationskällor. Alla källor refereras med undantag för beskrivning av allmänna förhållanden eller där Lifos expert är en källa, vilket i så fall anges. För att få en så fullständig bild som möjligt bör rapporten inte användas exklusivt som underlag i samband med avgörandet av ett enskilt ärende utan tillsammans med andra källor. Informationen i rapporten återspeglar inte Migrationsverkets officiella ståndpunkt i en viss fråga och Lifos har ingen avsikt att genom rapporten göra politiska eller rättsliga ställningstaganden. Temarapport: Militär utveckling och territoriell kontroll i Syriens 14 provinser 2017-01-12, version 1.0 Lifos – Center för landinformation och landanalys inom migrationsområdet © Migrationsverket (Swedish Migration Agency), 2017 Publikationen kan laddas ner från http://lifos.migrationsverket.se 2017-01-12, version 1.0 2 (49) Lifos Temarapport: Militär utveckling och territoriell kontroll i Syriens 14 provinser Innehåll 1. English summary ................................................................................... -

The Larger Battle for Aleppo

THE LARGER BATTLE FOR ALEPPO THE REMOVAL OF US TROOPS FROM SYRIA AND THE STRUGGLE FOR PROVINCIAL ALEPPO JUNE 2019 BY CONNOR KUSILEK U.S. Soldier near Manbij, Syria. Source: U.S. Department of Defense. Staff Sgt. Timothy R. Koster, June 2018. THE LARGER BATTLE FOR ALEPPO THE REMOVAL OF US TROOPS FROM SYRIA AND THE STRUGGLE FOR PROVINCIAL ALEPPO EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Aleppo city has fallen. The Assad Regime has re-imposed its authority over eastern Aleppo. However, the relevancy of the Aleppo Governorate is no less diminished. As the war enters its eighth year, the majority of fighting has shifted north where the many actors have gathered to determine the fate of their claimed territories. Under the control of various militaries, both foreign and domestic, the nearly six million inhabitants of the region are left with little control over who governs them and how. This paper initially served as a response to US President Donald Trump’s announcement that American troops would be removed from Syria. Since then, it has grown into a larger project examining the many actors at play in the governorate, their motives and positions, and the effect US withdrawal will have on the existing balance of power. This paper attempts to detail the reality on the ground and provide insight into the complex nature of a war with shifting alliances and foreign proxies that provides little voice for the civilians who suffer most. Any lasting peace will have to guarantee the free return of all displaced people and equal political representation of all communities in the Governorate of Aleppo, including Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmen. -

Security Council Distr.: General 22 May 2014

United Nations S/2014/365 Security Council Distr.: General 22 May 2014 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the implementation of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014) I. Introduction 1. The present report is the third submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), in which the Security Council requested the Secretary-General to report, every 30 days, on the implementation of the resolution by all parties in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The report covers the period from 22 April to 19 May 2014. The information contained in the report is based on the data available to the United Nations actors on the ground and reports from open sources and sources of the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic. II. Major developments A. Political/military 3. Violence continued unabated across the Syrian Arab Republic during the reporting period, including but not limited to Aleppo, Hama, Deir-ez-Zor, Homs, Damascus, Rural Damascus and Dar’a governorates. Indiscriminate aerial strikes and shelling by government forces resulted in deaths, injuries and large-scale displacement of civilians, while armed opposition groups also continued indiscriminate shelling and the use of car bombs in populated civilian areas. 4. In Aleppo, indiscriminate air strikes by government forces continued in the city and surrounding countryside. Reports indicate that hundreds of people, including civilians, have been killed or injured and tens of thousands have continued to flee the city. Human Rights Watch, which conducted an analysis of satellite imagery from late April to early May, concluded that over 140 major damage sites were strongly consistent with the impact of air strikes. -

Population Displacement Strategies in Civil Wars by Adam G

Making Migrations: Population Displacement Strategies in Civil Wars by Adam G. Lichtenheld A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Ron Hassner, Chair Associate Professor Saira Mohamed Associate Professor Leonardo Arriola Associate Professor Aila Matanock Summer 2019 Making Migrations: Population Displacement Strategies in Civil Wars Copyright 2019 by Adam G. Lichtenheld 1 Abstract Making Migrations: Population Displacement Strategies in Civil Wars by Adam G. Lichtenheld Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Ron Hassner, Chair Why do armed groups uproot civilians in wartime? This dissertation identifies variation across civil wars in three population displacement strategies – cleansing, depopulation, and forced relocation – and tests different explanations for their use. I develop a new “assortative” theory of displacement, which argues that while some strategies (cleansing) aim to expel undesirable or disloyal populations, others (forced relocation, and perhaps depopulation) seek to identify the undesirables or the disloyal in the first place. When combatants lack information about opponents’ identities and civilians’ loyalties, they can use human mobility to infer wartime sympathies through “guilt by location.” Triggering displacement forces people to send costly and visible signals of loyalty based on whether, and where, they flee. This makes communities more “legible,” enabling combatants to use people’s movements as a continuous indicator of affiliation and allegiance; and to extract rents and recruits from the population. I therefore show that in some cases, displacement is attractive because it offers unique solutions to information and resource problems in civil wars by acting as a sorting mechanism and a force multiplier.