Advance Unedited Version Distr.: General 2 July 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib May 3rd, 2016 ― Doha: Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS) is proceeding with its support of the medical sector in Syria, by providing medications, medical equipment, and fuel to help health facilities absorb the increasing numbers of injuries, amid deteriorating health conditions countrywide due to the conflict. Lately, QRCS personnel in Syria procured 30,960 liters of fuel to operate power generators at the surgical hospital in Aqrabat, Idlib countryside. These $17,956 supplies will serve the town's 100,000 population and 70,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). In coordination with the Health Directorate in Idlib, QRCS is operating and supporting the hospital with fuel, medications, medical consumables, and operational costs. Working with a capacity of 60 beds and four operating rooms, the hospital is specialized in orthopedics and reconstructive procedures, in addition to general medicine and dermatology clinics. In western Aleppo countryside, QRCS personnel delivered medical consumables and serums worth $2,365 to the health center of Kafarnaha, to help reduce the pressure on the center's resources, as it is located near to the clash frontlines. Earlier, a needs assessment was done to identify the workload and shortfalls, and accordingly, the needed types of supplies were provided to serve around 1,500 patients from the local community and IDPs. In relation to its $200,000 immediate relief intervention launched last week, QRCS is providing medical supplies, fuel, and food aid; operating AlSakhour health center for 100,000 beneficiaries in Aleppo City, at a cost of $185,000; securing strategic medical stock for the Health Directorate; providing the municipal council with six water tankers to deliver drinking water to 350,000 inhabitants at a cost of $250,000; arranging for more five tankers at a cost of $500,000; providing 1,850 medical kits, 28,000 liters of fuel, and water purification pills; and supplying $80,000 worth of food aid. -

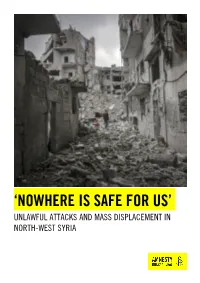

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects

JOURNAL OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 VOL. 43, NO. 1, 74–84 https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1410919 The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects: A View from the Ground Neil Brodiea and Isber Sabrineb aUniversity of Oxford, Oxford, UK; bUniversitat de Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The illegal excavation and trade of cultural objects from Syrian archaeological sites worsened Syria; looting; cultural markedly after the outbreak of civil disturbance and conflict in 2011. Since then, the damage to objects; coins; policy archaeological heritage has been well documented, and the issue of terrorist funding explored, but hardly any research has been conducted into the organization and operation of theft and trafficking of cultural objects inside Syria. As a first step in that direction, this paper presents texts of interviews with seven people resident in Syria who have first-hand knowledge of the trade, and uses information they provided to suggest a model of socioeconomic organization of the Syrian war economy regarding the trafficking of cultural objects. It highlights the importance of coins and other small objects for trade, and concludes by considering what lessons might be drawn from this model to improve presently established public policy. Introduction conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/). Nevertheless, most of what is known about illegal excavation and trade inside Like that of many countries in the Middle East and North Syria comes from some of the better media reporting, Africa (MENA) region, for the past few decades the archaeo- which has on occasion managed to access people with first- logical heritage of Syria has been robbed of cultural objects for hand knowledge or experience of the problem. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

The Syrian Crisis: an Analysis of Neighboring Countries' Stances

POLICY ANALYSIS The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Series: Policy Analysis Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. ____________________________ The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non-Arab researchers. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies PO Box 10277 Street No. 826, Zone 66 Doha, Qatar Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651 www.dohainstitute.org Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Lebanese Position toward the Syrian Revolution 1 Factors behind the Lebanese stances 8 Internationally 14 Domestically 14 The Jordanian Stance 15 Regional and International Influences 18 The Syrian Revolution and the Arab Levant 22 NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES’ STANCES ON SYRIA Introduction The Arab Levant region has significant geopolitical importance in the global political map, particularly because of its diverse ethnic and religious identities and the complexity of its social and political structures. -

Rojavadevrimi+Full+75Dpi.Pdf

Kitaba ilişkin bilinmesi gerekenler Elinizdeki kitabın orijinali 2014 ve 2015 yıllarında Almanca dilinde üç yazar tarafından yazıldı ve Rosa Lüksemburg Vakfı’nın desteğiyle “VSA Verlag” adlı yayınevi tarafından Almanya’da yayınlandı. 2018 yılında Almanca dilinde 4. baskısı güncellenip basılarak önemli ilgi gören bu kitap, 2016 Ekim ayında “Pluto Press” adlı yayınevi tarafından İngilizce dilinde Birleşik Krallık ‘ta yayınlandı. Bu kitabın İngilizce çevirisi ABD’de yaşayan yazar ve aktivist Janet Biehl tarafından yapıldı ve sonrasında üç yazar tarafından 2016 ilkbaharında güncellendi. En başından beri kitabın Türkçe dilinde de basılıp yayınlanası için bir planlama yapıldı. Bu amaçla bir grup gönüllü İngilizce versiyonu temel alarak Türkçe çevirisini yaptı. Türkiye’deki siyasal gelişme ve zorluklardan dolayı gecikmeler ortaya çıkınca yazarlar kitabın basılmasını 2016 yılından daha ileri bir tarihe alma kararını aldı. Bu sırada tekrar Rojava’ya giden yazarlar, elde ettikleri bilgilerle Türkçe çeviriyi doğrudan Türkçe dilinde 2017 ve 2018 yıllarında güncelleyip genişletti. Bu gelişmelere redaksiyon çalışmaları da eklenince kitabın Türkçe dilinde yayınlanması 2018 yılında olması gerekirken 2019 yılına sarktı. 2016 yılından beri kitap ayrıca Farsça, Rusça, Yunanca, İtalyanca, İsveççe, Polonca, Slovence, İspanyolca dillerine çevrilip yayınlandı. Arapça ve Kürtçe çeviriler devam etmektedir. Kitap Ağustos 2019’da yayınlandı. Ancak kitapta en son Eylül 2018’de içeriksel güncellenmeler yapıldı. 2018 yazın durum ve atmosferine göre yazıldı. Kitapta kullanılan resimlerde eğer kaynak belirtilmemişse, resimler yazarlara aittir. Aksi durumda her resmin altında resimlerin sahibi belirtilmektedir. Kapaktaki resim Rojava’da kurulmuş kadın köyü Jinwar’ı göstermekte ve Özgür Rojava Kadın Vakfı’na (WJAR) aittir. Bu kitap herhangi bir yayınevi tarafından yayınlanmamaktadır. Herkes bu kitaba erişimde serbesttir. Kitabı elektronik ve basılı olarak istediğiniz gibi yayabilirsiniz, ancak bu kitaptan gelir ve para elde etmek yazarlar tarafından izin verilmemektedir. -

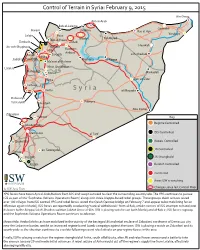

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “Torpedoed” by the West? By Adam Larson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, May 02, 2013 Theme: US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA Since the perplexing conflict in Syria first broke out two years ago, the Western powers’ assistance to the anti-government side has been consistent, but relatively indirect. The Americans and Europeans lay the mental, legal, diplomatic, and financial groundwork for regime change in Syria. Meanwhile, Arab/Muslim allies in Turkey and the Persian Gulf are left with the heavy lifting of directly supporting Syrian rebels, and getting weapons and supplementary fighters in place. The involvement of the United States in particular has been extremely lackluster, at least in comparison to its aggressive stance on a similar crisis in Libya not long ago. Hopes of securing major American and allied force, preferrably a Libya-style “no-fly zone,” always leaned most on U.S. president Obama’s announcement of December 3, 2012, that any use of chemical weapons (CW) by the Assad regime – or perhaps their simple transfer – will cross a “red line.” And that, he implied, would trigger direct U.S. intervention. This was followed by vague allegations by the Syrian opposition – on December 6, 8, and 23 – of government CW attacks. [1] Nothing changed, and the allegations stopped for a while. However, as the war entered its third year in mid-March, 2013, a slew of new allegations came flying in. This started with a March 19 attack on Khan Al-Assal, a contested western district of Aleppo, killing a reported 25-31 people. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car.