'Thanatosepoesen' Changing Attitudes in Athenian Mourning: a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optimized Handling. the New Generation of Wet Stone Grinders

Optimized Handling. The new generation of wet stone grinders. Wet stone grinder FLEX and natural stone. A special relationship. Natural stone has its own laws. That call for special experts. Specialists who know how to read the stone. Who by the nuances and shades of the colours in the stone can recognise the unique masterpiece that a completely sculptured piece of work can evolve, but to realize this vision good tools are needed. For over 80 years FLEX is the competent and innovative partner for working with natural stone. Over this course of time a comprehensive range of machines has been developed in close co-operation with experienced stone masons. A product range that sets the industry standards for robustness and reliability also with handling and maintenance but especially by working safety when using water. The long-time competence of FLEX also includes the knowledge that FLEX engineers have gained about the nature of stone, its characteristics, and its sensitivities. That is why a FLEX machine of course does not damage or soil the valuable “natural stone”, but professionally processes and preserves it. As in every perfect relationship allows you to work to perfection. Wet stone grinder The FLEX PRCD safety switch ensures electrical safety when undertaking wet sanding. Is released practi- cally immediately (< 15 milliseconds)at the required response sensitivity. Complete with accidental restart safeguard on the power being interrupted. The contour plug is standard equipment on many wet grinders. It can be plugged only into the isolation transformer and not into the power outlet. The extensive FLEX natural stone range provides everything - from pressurized water tank, isolating transformers and safety vacuum cleaners to grinding discs, abrasive rings and diamond tools. -

An Osteobiography of Roman Burial from Oğlanqala, Azerbaijan

Death on the Imperial Frontier: an Osteobiography of Roman Burial from Oğlanqala, Azerbaijan THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Selin Elizabeth Nugent, B.S. Graduate Program in Anthropology The Ohio State University 2013 Master’s Examination Committee: Clark S. Larsen, Advisor Mark Hubbe Samuel Stout Barbara Piperata Copyrighted by Selin Elizabeth Nugent 2013 Abstract In 2011, excavations at the Iron Age archaeological site of Oğlanqala in Naxçivan, Azerbaijan uncovered unexpected human remains dating to the early Roman period (2 B.C. - c. 14 A.D.). At Oğlanqala, numerous post-Iron Age interments from the early 20th century have been recovered. However, the early Roman burial represents the only Roman interment discovered at the site as well as in the South Caucasus. Burial WWE.1 was situated at the base of the Oğlanqala Iron Age citadel and consisted of a single individual (Individual 21) placed in a seated position inside a large pithos, or urn. While urn burial is a common practice in the Caucasus, the individual was accompanied by a large quantity of fine Roman material objects rarely found in this region, including Augustan denarii, glass unguentaria, gold inlayed intaglio rings on the fingers, a ceramic round bottom vessel, and a large glass bead. This paper presents a detailed analysis of the bioarchaeological identity of Individual 21, focusing on age, stress, status, and mobility and how these factors relate to the unusual burial style. Osteological and oxygen (18O /16O) stable isotope analysis, archaeological context of the burial, and the historical record provide the basis to identify the individual. -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

Aizanitis Bölgesi Mezar Taşlari

T.C PAMUKKALE ÜNİVERİSTESİ ARKEOLOJİ ENSTİTÜSÜ Doktora Tezi Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı Arkeoloji Doktora Programı AİZANİTİS BÖLGESİ MEZAR TAŞLARI Zerrin ERDİNÇ Danışman Prof. Dr. Elif ÖZER 2020 DENİZLİ DOKTORA TEZİ ONAY FORMU Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı, Doktora Programı öğrencisi Zerrin ERDİNÇ tarafından Prof. Dr. Elif ÖZER yönetiminde hazırlanan “Aizanitis Bölgesi Mezar Taşları” başlıklı tez aşağıdaki jüri üyeleri tarafından 24.02.2020 tarihinde yapılan tez savunma sınavında başarılı bulunmuş ve Doktora Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. Jüri Başkanı-Danışman Prof. Dr. Elif ÖZER Jüri Jüri Prof. Dr. Celal Şimşek Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Sabri ALANYALI Jüri Jüri Prof. Dr. Bilal SÖĞÜT Prof. Dr. Ertekin Doksanaltı Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yönetim Kurulu’nun …………..tarih ve ………….. sayılı kararıyla onaylanmıştır. Prof. Dr. Celal ŞİMŞEK Enstitü Müdürü Bu tezin tasarımı, hazırlanması, yürütülmesi, araştırmalarının yapılması ve bulgularının analizlerinde bilimsel etiğe ve akademik kurallara özenle riayet edildiğini; bu çalışmanın doğrudan birincil ürünü olmayan bulguların, verilerin ve materyallerin bilimsel etiğe uygun olarak kaynak gösterildiğini ve alıntı yapılan çalışmalara atıfta bulunulduğunu beyan ederim. İmza Zerrin ERDİNÇ ÖNSÖZ Aizanoi Phrygia Bölgesi’nin en önemli kentlerinden birisidir. Hellenistik ve Roma dönemlerinde stratejik konumu ve Zeus Tapınağı ile bölgenin kilit noktası haline gelmiştir. Özellikle Roma Dönemi’nde Aizanoi territoryumuna verilen isim olan Aizanitis Bölgesi çevresindeki kentlerden daha önemli bir konumda yer almış, Meter Steunene kutsal alanı ve Zeus tapınağı ile çevre kentlerin de dini merkezi haline gelmiştir. 2016 yılından bu yana bu güzel kentte arkeolojiye emek veren bu harika ekibe dâhil olduğum için kendimi çok şanslı saymaktayım. Bana bu şansı veren ve inanarak bana bu malzemeyi emanet eden saygıdeğer hocam Prof. Dr. Elif Özer’e sonsuz teşekkürlerimi sunuyorum. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

Chapter-8.Pdf

8 HISTORY FOCUS Connecting Art and History from 500 BCE-500- CE Major civilizations and empires developed an early but short-lived enjoying outdoor sports are common, flourishedaround the world at this formof democracy. In the fourth as in the Banqueters and Musicians time (see Map 4). The great wealth and century BCE, the Macedonians from the Tomb of the Leopards power of these empires produced elite conquered the Greeks and, under (Fig. 8.9). The Sarcophagus with classes who commissioned amazing Alexander the Great, invaded Persia Reclining Couple (Fig. 8.8) indicates works of art, among which were and defeated King Darius. Alexander's that Etruscan women enjoyed monumental tombs and funerary art empire, stretching as far as India and considerable independence. They that preserved their fame. the Middle East, further spread Greek attended symposia and sporting In Greece, which consisted of influence. events, were equals at banquets with independent city-states, 500-338 BCE The Etruscan civilization, their husbands, owned property is considered the Classical period. consisting of city-states, occupied independently, and likely had a In Athens, artworks reflectedGreek much of central Italy. What we know high rate of literacy. Beginning in humanism with their idealized yet about the Etruscans comes largely 509 BCE, the Romans began naturalistic representations of the from excavations of their tombs chipping away at Etruria, and human figure,as seen in the Grave and funerary art. Tomb paintings of they completely overwhelmed the Stele ofHegeso (Fig. 8.15). Athens also lively people feasting, dancing, or Etruscans by 273 BCE. Map 4 The Assyrian and Persian Empires. -

Alexander the Great

ROYAL TREASURES 0. ROYAL TREASURES - Story Preface 1. LEARNING FROM ARISTOTLE 2. THE YOUNG ALEXANDER 3. ALEXANDER'S HOMETOWN 4. ASSASSINATION OF PHILIP II 5. DISCOVERY OF PHILIP'S TOMB 6. ROYAL TREASURES 7. ALEXANDER'S BEQUEST 8. ALEXANDER'S EARLY CONQUESTS 9. CHASING DARIUS III 10. GAUGAMELA AND THE END OF DARIUS 11. ELEPHANTS IN WAR 12. VICTORY IN INDIA 13. GOING HOME 14. ALEXANDER'S DEATH 15. ALEXANDER'S JOURNEY IN PICTURES 16. THE REST OF THE STORY Among other treasures in the royal tomb near the ancient capital of Macedonia, archeologists found a small ivory portrait. Scholars believe it depicts Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. With reconstructions, cutaways and pictures of the Vergina tombs and their contents, we can gain some understanding of what life was like during the time of Alexander the Great. For descriptive purposes only, we refer to the tomb believed by some (but not all) to be "Philip's tomb." Tomb under excavation. Cutaway of Philip's tomb. Interior door of tomb during excavation. Tombs of Macedonian royalty were richly decorated. Facade of Philip's tomb during excavation with detail of the painted top (called a geison). Excavated tomb, with the sky above, has a frieze across the top. Macedonians, like Philip, were great hunters. The painting across the top of the tomb depicts hunting scenes. West side of tomb with sarcophagus. Small sarcophagus with gold larnax inside. The gold larnax containing textiles, gold, ashes and bones. Cloth and gold inside the larnax. Reconstruction of wooden kline. Left and right ends of kline in Bella Mound. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

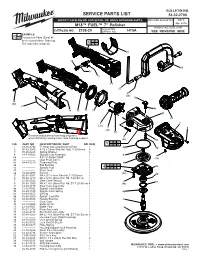

Service Parts List 54-32-2700 Specify Catalog No

BULLETIN NO. SERVICE PARTS LIST 54-32-2700 SPECIFY CATALOG NO. AND SERIAL NO. WHEN ORDERING PARTS REVISED BULLETIN DATE M18™ FUEL™ 7" Polisher Apr. 2016 WIRING INSTRUCTION STARTING CATALOG NO. 2738-20 SERIAL NO. H15A SEE REVERSE SIDE EXAMPLE: 00 0 Component Parts (Small #) Are Included When Ordering 14 15 The Assembly (Large #). 30 19 21 20 16 24 17 18 19 22 23 (2x) 9a 14 (8x) 21 9b 15 13 11 10 9f 5 2 25 8 3 2 7 (2x) 7 3 6 6 (2x) 1 12 4 Recommended screw fastening sequence 8 when installing housing cover onto housing support (4x) 9c 9a 9b 9c FIG. PART NO. DESCRIPTION OF PART NO. REQ. 9 9d 9e 9f 1 49-36-2792 7" Hook and Loop Backing Plate 1 4g 9d 2 06-82-2380 8-32 x 12mm Pan Hd. Tapt. T-20 Screw 6 3 05-90-0225 Spring Washer 6 4 14-73-0022 Spindle Hub Assembly 1 9e 5 4a --------------- 5/8"-11 Output Shaft 1 (2x) 4b --------------- Dust Proof Cover 1 4c 34-80-0210 Retaining Ring 1 4f 4d --------------- Ball Bearing 1 4a 4b 4c 4d 4e 4e --------------- Spindle Hub 1 4 4e 4f 4g 4f --------------- Bevel Gear 1 3 4g 34-40-0097 O-Ring 1 (4x) 4d 5 06-82-3007 M4 x 0.7 x 8mm Pan Hd. T-20 Screw 2 6 05-88-1210 M4 x 0.7 x 14mm Pan Hd. T-20 Screw 1 7 31-55-0022 Gear Case Shroud 1 2 4c 8 05-88-1300 M4 x 1.4 x 28mm Pan Hd. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Pergamonmuseum Das Panorama Museumsinsel Berlin

DE Information und Lageplan PERGAMONMUSEUM DAS PANORAMA MUSEUMSINSEL BERLIN 1 Aussichtsplattform 360°-Panorama ANTIKENSAMMLUNG BERLIN YADEGAR ASISI Im Rahmen des Masterplans Museumsinsel werden alle histo- Diese Ausstellung basiert auf dem Wunsch, ein langjähriges, rischen Museumsbauten grundlegend saniert und modernisiert. einzigartiges Gemeinschaftsprojekt der Antikensammlung der Als größtes Gebäude der Insel ist nun das Pergamonmuseum mit Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin und des Künstlers Yadegar Asisi seinen Rekonstruktionen antiker Architektur an der Reihe. Der zu vertiefen. Die Intention war und ist, Geschichte nicht allein Pergamonaltar, das bekannteste und namengebende Monument in gewohnter Art und Weise wissenschaftlich zu vermitteln, son- des Hauses, konnte aus konservatorischen und technischen dern als ein Erlebnis zu präsentieren und somit die Aussagekraft Gründen nicht vollständig abgebaut werden. Stattdessen bie- zu vervielfältigen. ten wir unseren Besuchern für die Zeit der Schließung mit dieser In einer weltweit einmaligen Zusammenarbeit sind 140 Jahre Ausstellung eine einzigartige Alternative: Meisterwerke der Anti- archäologische Forschungen und die Arbeit eines zeitgenössi- 6 kensammlung aus der hellenistischen Königsresidenz Pergamon schen Künstlers synergetisch ineinander verwoben und bilden mit Teilen des Altars, bereichert durch das 360°-Panorama und ein spektakuläres Gesamtwerk. multimediale Inszenierungen. Die Ausstellung zeigt Spitzenstücke der klassischen Antike aus Die Antikensammlung knüpft damit an die erfolgreiche Zusam- dem Pergamonmuseum und hebt besondere Artefakte in eigens 5 menarbeit mit Yadegar Asisi bei der Sonderausstellung ›Perga- für dieses Ausstellungsgebäude entwickelten Installationen mon. Panorama der antiken Metropole‹ des Jahres 2011/2012 an. hervor. Im Zentrum steht die Installation des 360°-Panoramas 4 von Yadegar Asisi, das Forschungsergebnisse und Sammlungs- 0 D objekte in einem Gesamtkunstwerk räumlich und emotional er- ANTIKENSAMMLUNG lebbar macht.