Inscribed Silver Plate from Tomb Ii at Vergina 337

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Alexander the Great

ROYAL TREASURES 0. ROYAL TREASURES - Story Preface 1. LEARNING FROM ARISTOTLE 2. THE YOUNG ALEXANDER 3. ALEXANDER'S HOMETOWN 4. ASSASSINATION OF PHILIP II 5. DISCOVERY OF PHILIP'S TOMB 6. ROYAL TREASURES 7. ALEXANDER'S BEQUEST 8. ALEXANDER'S EARLY CONQUESTS 9. CHASING DARIUS III 10. GAUGAMELA AND THE END OF DARIUS 11. ELEPHANTS IN WAR 12. VICTORY IN INDIA 13. GOING HOME 14. ALEXANDER'S DEATH 15. ALEXANDER'S JOURNEY IN PICTURES 16. THE REST OF THE STORY Among other treasures in the royal tomb near the ancient capital of Macedonia, archeologists found a small ivory portrait. Scholars believe it depicts Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. With reconstructions, cutaways and pictures of the Vergina tombs and their contents, we can gain some understanding of what life was like during the time of Alexander the Great. For descriptive purposes only, we refer to the tomb believed by some (but not all) to be "Philip's tomb." Tomb under excavation. Cutaway of Philip's tomb. Interior door of tomb during excavation. Tombs of Macedonian royalty were richly decorated. Facade of Philip's tomb during excavation with detail of the painted top (called a geison). Excavated tomb, with the sky above, has a frieze across the top. Macedonians, like Philip, were great hunters. The painting across the top of the tomb depicts hunting scenes. West side of tomb with sarcophagus. Small sarcophagus with gold larnax inside. The gold larnax containing textiles, gold, ashes and bones. Cloth and gold inside the larnax. Reconstruction of wooden kline. Left and right ends of kline in Bella Mound. -

Mediterranean Divine Vintage Turkey & Greece

BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Neapolis Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Abdera Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA JOINAllante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Elimia PydnaMEDITERRANEAN Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Dasaki Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos Torone Hephaistia Dorylaeum BOZCAADA Sigeion Kenchreai Omphatium Gonnus Skione Limnos MYSIA Uludag ESKİŞEHİR Eritium DIVINE VINTAGE Derecik Basilica Sidari Oxynia Myrina Kaz Mt. Passaron Soufli Troas Kebrene Skepsis UNESCO Meliboea Cassiope Gure bath BALIKESİR Dikilitaş Kanlıtaş Höyük Aiginion Neandra Karacahisar Castle Meteora Antandros Adramyttium Corfu UNESCO Larissa Lamponeia Dodoni Theopetra Gülpinar Pioniai Kulluoba Hamaxitos Seyitömer Höyük Keçi çayırı Syvota KÜTAHYA Grava Polimedion Assos Gerdekkaya Assos Mt.Pelion A E GTURKEY E A N S E A &Pyrrha GREECEMadra Mt. (Cotiaeum) Kumbet Lefkimi Theudoria Pherae Mithymna Midas City Ellina EPIRUS Passandra Perperene Lolkos/Gorytsa Antissa Bahses Mt. -

Thesis Title

To my parents, Athanassios Kravvas and Eleni Lioudi-Kravva To my children, Bigina and Thanassis Without them I feel that my accomplishments would be somehow incomplete… Acknowledgements There are some people who have contributed –one way or another– to this final product. I would like to thank my Ph.D. supervisors Pat Caplan and Victoria Goddard for their continuous support, guidance and trust in my project and myself. I am grateful to Rena Molho for her help and support through all these years. Stella Salem constantly enhanced my critical understanding and problematised many of my arguments. Of course, I should not forget to mention all my informants for sharing with me their ideas, their fears and who made me feel “at home” whenever they invited me to their homes. I would also like to thank Eleonora Skouteri–Didaskalou a gifted academic who tried to teach me more than ten years ago what anthropology is and why studying it entails a kind of magic. Last but not least I would like to express my gratitude to Ariadni Antonopoulou for helping me with the final version of the text. CONTENTS Introduction: What is to be “cooked” in this book? 1 1. Introducing the Jews of Thessaloniki: Views from within 9 About the present of the Community 9 Conceptualising Jewishness 13 “We are Sephardic Jews” 17 “We don‟t keep kosher but” 20 2. Conceptual “ingredients”: We are what we eat or we eat because we 24 want to belong Part A. Theories: Food as an indicator of social relationships 25 Food and the local-global interplay 29 Ethnicity and boundaries 32 Boundaries and communities 35 Eating food, constructing boundaries and making communities 42 Greece “through the looking glass” and the study of Macedonia 44 Part B. -

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period. -

13 - E5 July 2011

COMMITTEE ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT DELEGATION TO GREECE 13 - E5 JULY 2011 source: http://kopiaste.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Programme of the delegation ........................................................................................ 3 List of Participants ...................................................................................................... 10 Itinerary Map............................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday 13 July 2011 ............................................................................................ 14 Description of projects ............................................................................................ 15 Information on Thessaloniki ................................................................................... 16 Thursday 14 July 2011................................................................................................ 17 Description of projects ............................................................................................ 18 Information on Kozani ............................................................................................ 21 Friday 15 July 2011..................................................................................................... 22 Description of projects ............................................................................................ 23 Information on Ioannina......................................................................................... -

Is the Mother of Alexander the Great in the Tomb at Amphipolis?

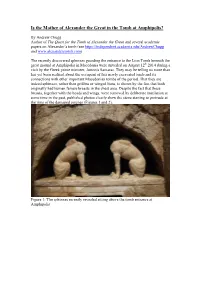

Is the Mother of Alexander the Great in the Tomb at Amphipolis? By Andrew Chugg Author of The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great and several academic papers on Alexander’s tomb (see https://independent.academia.edu/AndrewChugg and www.alexanderstomb.com) The recently discovered sphinxes guarding the entrance to the Lion Tomb beneath the great mound at Amphipolis in Macedonia were unveiled on August 12th 2014 during a visit by the Greek prime minister, Antonis Samaras. They may be telling us more than has yet been realised about the occupant of this newly excavated tomb and its connections with other important Macedonian tombs of the period. That they are indeed sphinxes, rather than griffins or winged lions, is shown by the fact that both originally had human female breasts in the chest area. Despite the fact that these breasts, together with the heads and wings, were removed by deliberate mutilation at some time in the past, published photos clearly show the stone starting to protrude at the rims of the damaged patches (Figures 1 and 2). Figure 1: The sphinxes recently revealed sitting above the tomb entrance at Amphipolis Figure 2: Close-up of the right-hand sphinx The tomb has been dated to the last quarter of the fourth century before Christ (325- 300BC) by the archaeologists, led by Katerina Peristeri. This was the period immediately following the death of Alexander the Great in 323BC. Sphinxes are not particularly common in high status Macedonian tombs of this era, but, significantly, sphinxes were prominent parts of the decoration of two thrones found in the late 4th century BC tombs of two Macedonian queens in the royal cemetery at Aegae (modern Vergina) in Macedonia. -

Περίληψη : Demetrius Poliorcetes (337 B.C.-283 B.C.) Was One of the Diadochi (Successors) of Alexander the Great

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Παναγοπούλου Κατερίνα Μετάφραση : Βελέντζας Γεώργιος Για παραπομπή : Παναγοπούλου Κατερίνα , "Demetrius Poliorcetes", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Κωνσταντινούπολη URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=7727> Περίληψη : Demetrius Poliorcetes (337 B.C.-283 B.C.) was one of the Diadochi (Successors) of Alexander the Great. He initially co-ruled with his father, Antigonus I Monophthalmos, in western Asia Minor and participated in campaigns to Asia and mainland Greece. After the heavy defeat and death of Monophthalmos in Ipsus (301 B.C.), he managed to increase his few dominions and ascended to the Macedonian throne (294-287 B.C.). He spent the last years of his life captured by Seleucus I in Asia Minor. Άλλα Ονόματα Poliorcetes Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 337/336 BC – Macedonia Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 283 BC – Asia Minor Κύρια Ιδιότητα Hellenistic king 1. Youth Son of Antigonus I Monophthalmos and (much younger) Stratonice, daughter of the notable Macedonian Corrhaeus, Demetrius I Poliorcetes was born in 337/6 B.C. in Macedonia and died in 283 B.C. in Asia Minor. His younger brother, Philip, was born in Kelainai, the capital of Phrygia Major, as Stratonice had followed her husband in the Asia Minor campaign. Demetrius spent his childhood in Kelainai and is supposed to have received mainly military education.1 At the age of seventeen he married Phila, daughter of the Macedonian general and supervisor of Macedonia, Antipater, and widow of Antipater’s expectant successor, Craterus. The marriage must have served political purposes, as Antipater had been appointed commander of the Macedonian district towards the end of the First War of the Succesors (321-320 B.C.). -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

Footsteps of Paul Day 1- Day 2- Phillippi, Kavala

Footsteps of Paul A CCO Trip Tentative Itinerary: April 28- May 6 Trip cost to be determined (estimated ~$4,900) Day 1- Arrive Thessaloniki (afternoon) Drive to Kavala Day 2- Phillippi, Kavala Today we discover the historic town of Phillippi with archaeological sites and monuments from Ancient, Roman and Byzantine eras. We will visit the tribunal where Paul was beaten, the prison where Paul and Silas were held, and the Baptistery of St Lydia, the church on the stream where Paul baptized Lydia, the first Christian convert in Europe. We return to Kavala, (Neapolis) which is one of Greece's most picturesque mainland port. Paul arrived at this port when landing in Greece. We can see a modern mosaic depicting Paul's vision and arrival at Neapolis. Footsteps of Paul A CCO Trip Tentative Itinerary: April 28- May 6 Trip cost to be determined (estimated ~$4,900) Day 3- Thessaloniki Today we travel to Thessaloniki to visit the 5th-century Church of Agios Dimitrios, a church renowned for mosaics and frescoes and St. George's Basilica, thought to be built over the synagogue where Paul preached; Highlights of the town includes the old city ramparts, the White Tower overlooking the harbor, and the Arch of Galerius that rises over the Via Egnatia, the church of St. Demetrius, dedicated to a Roman military officer who was martyred for his faith in Christ by Emperor Galerius. Our day will include a visit a traditional winery for late lunch Day 4- Thessaloniki, Berea, Vergina Outside of Thessaloniki, we will visit the famous Gerovassiliou winery and its museum before traveling to Berea, where Paul preached on his first missionary journey. -

In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia

Advance press kit Exhibition From October 13, 2011 to January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia Contents Press release page 3 Map of main sites page 9 Exhibition walk-through page 10 Images available for the press page 12 Press release In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Exhibition Ancient Macedonia October 13, 2011–January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall This exhibition curated by a Greek and French team of specialists brings together five hundred works tracing the history of ancient Macedonia from the fifteenth century B.C. up to the Roman Empire. Visitors are invited to explore the rich artistic heritage of northern Greece, many of whose treasures are still little known to the general public, due to the relatively recent nature of archaeological discoveries in this area. It was not until 1977, when several royal sepulchral monuments were unearthed at Vergina, among them the unopened tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father, that the full archaeological potential of this region was realized. Further excavations at this prestigious site, now identified with Aegae, the first capital of ancient Macedonia, resulted in a number of other important discoveries, including a puzzling burial site revealed in 2008, which will in all likelihood entail revisions in our knowledge of ancient history. With shrewd political skill, ancient Macedonia’s rulers, of whom Alexander the Great remains the best known, orchestrated the rise of Macedon from a small kingdom into one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world, before defeating the Persian Empire and conquering lands as far away as India. -

Contesting the Greatness of Alexander the Great: the Representation of Alexander in the Histories of Polybius and Livy

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY Nikolaus Leo Overtoom, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History By investigating the works of Polybius and Livy, we can discuss an important aspect of the impact of Alexander upon the reputation and image of Rome. Because of the subject of their histories and the political atmosphere in which they were writing - these authors, despite their generally positive opinions of Alexander, ultimately created scenarios where they portrayed the Romans as superior to the Macedonian king. This study has five primary goals: to produce a commentary on the various Alexander passages found in Polybius’ and Livy’s histories; to establish the generally positive opinion of Alexander held by these two writers; to illustrate that a noticeable theme of their works is the ongoing comparison between Alexander and Rome; to demonstrate Polybius’ and Livy’s belief in Roman superiority, even over Alexander; and finally to create an understanding of how this motif influences their greater narratives and alters our appreciation of their works. CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY By Nikolaus Leo Overtoom Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Chair Professor Judith P. Hallett Professor Kenneth G. Holum © Copyright by Nikolaus Leo Overtoom 2011 Dedication in amorem matris Janet L.