The Banality of "Ethnic War": Yugoslavia and Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case: Branko Grujić Et Al – 'Zvornik' War Crimes Chamber Belgrade District Court, Republic of Serbia Case Number: KV.5/05

Case: Branko Grujić et al – ‘Zvornik’ War Crimes Chamber Belgrade District Court, Republic of Serbia Case number: KV.5/05 Trial Chamber: Tatjana Vuković, Trial Chamber President, Vesko Krstajić, Judge, Trial Chamber Member, Olivera Anđelković, Judge, Trial Chamber Member War Crimes Prosecutor: Milan Petrović Accused: Branko Grujić, Branko Popović, Dragan Slavković a.k.a. Toro, Ivan Korać a.k.a. Zoks, Siniša Filipović a.k.a. Lopov, and Dragutin Dragićević a.k.a. Bosanac Report: Nataša Kandić, Executive Director of the Humanitarian Law Centre (HLC), and Dragoljub Todorović, Attorney, victims representatives 30 November 2005 Branko Popović’s defence Branko Popović, who used the alias of Marko Pavlović, was in charge of the Zvornik TO Staff. He was born and lived in Sombor in Serbia. Besides working for the socially-owned company Sunce, he had a firm of his own and helped Serb refugees from Croatia through the „Krajina‟ association. The first person from Zvornik he met, through Rade Kostić, the deputy minister of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Serb Krajina, was witness K. The meetings in Mali Zvornik in Serbia Shortly before the war, that is, at the end of March 1992, the SDS president in Zvornik invited Popović to a meeting at the Hotel Jezero in Mali Zvornik with volunteers from Serbia who wanted to help and to give an „inspiration to the Serb people should it come to war.‟ The accused said that it was there that he met Vojin Vučković a.k.a. Žuća, a man named Rankić, a man named Bogdanović, and Žuća‟s brother Dušan Vučković a.k.a. -

Décision Relative À La Requête De L'accusation Aux Fins De Dresser Le Constat Judiciaire De Faits Relatifs À L'affaire Krajisnik

IT-03-67-T p.48378 NATIONS o ~ ~ 31 g -.D ~s 3b 1 UNIES J ~ JUL-j ~D)D Tribunal international chargé de Affaire n° : IT-03-67-T poursuivre les personnes présumées responsables de violations graves du Date: 23 juillet 2010 droit international humanitaire commises sur le territoire de l'ex Original: FRANÇAIS Yougoslavie depuis 1991 LA CHAMBRE DE PREMIÈRE INSTANCE III Composée comme suit: M.le Juge Jean-Claude Antonetti, Président M.le Juge Frederik Harhoff Mme. le Juge Flavia Lattanzi Assisté de: M. John Hocking, greffier Décision rendue le: 23 juillet 2010 LE PROCUREUR cl VOJISLAV SESELJ DOCUMENT PUBLIC A VEC ANNEXE DÉCISION RELATIVE À LA REQUÊTE DE L'ACCUSATION AUX FINS DE DRESSER LE CONSTAT JUDICIAIRE DE FAITS RELATIFS À L'AFFAIRE KRAJISNIK Le Bureau du Procureur M. Mathias Marcussen L'Accusé Vojislav Seselj IT-03-67-T p.48377 1. INTRODUCTION 1. La Chambre de première instance III (<< Chamb re ») du Tribunal international chargé de poursuivre les personnes présumées responsables de violations graves du droit international humanitaire commises sur le territoire de l'ex-Yougoslavie depuis 1991 (<< Tribunal ») est saisie d'une requête aux fins de dresser le constat judiciaire de faits admis dans l'affaire Le Procureur cl Momcilo Krajisnik, en application de l'article 94(B) du Règlement de procédure et de preuve (<< Règl ement »), enregistrée par le Bureau du Procureur (<< Ac cusation ») le 29 avril 2010 (<< Requête») 1. H. RAPPEL DE LA PROCÉDURE 2. Le 29 avril 2010, l'Accusation déposait sa Requête par laquelle elle demandait que soit dressé le constat judiciaire de 194 faits tirés du jugement rendu dans l'affaire Krajisnik (<< Jugement ») 2. -

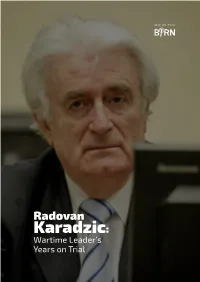

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court. -

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina

Remembering Wartime Rape in Post-Conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarah Quillinan ORCHID ID: 0000-0002-5786-9829 A dissertation submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 School of Social and Political Sciences University of Melbourne THIS DISSERTATION IS DEDICATED TO THE WOMEN SURVIVORS OF WAR RAPE IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA WHOSE STRENGTH, FORTITUDE, AND SPIRIT ARE TRULY HUMBLING. i Contents Dedication / i Declaration / iv Acknowledgments / v Abstract / vii Note on Language and Pronunciation / viii Abbreviations / ix List of Illustrations / xi I PROLOGUE Unclaimed History: Memoro-Politics and Survivor Silence in Places of Trauma / 1 II INTRODUCTION After Silence: War Rape, Trauma, and the Aesthetics of Social Remembrance / 10 Where Memory and Politics Meet: Remembering Rape in Post-War Bosnia / 11 Situating the Study: Fieldwork Locations / 22 Bosnia and Herzegovina: An Ethnographic Sketch / 22 The Village of Selo: Republika Srpska / 26 The Town of Gradić: Republika Srpska / 28 Silence and the Making of Ethnography: Methodological Framework / 30 Ethical Considerations: Principles and Practices of Research on Rape Trauma / 36 Organisation of Dissertation / 41 III CHAPTER I The Social Inheritance of War Trauma: Collective Memory, Gender, and War Rape / 45 On Collective Memory and Social Identity / 46 On Collective Memory and Gender / 53 On Collective Memory and the History of Wartime Rape / 58 Conclusion: The Living Legacy of Collective Memory in Bosnia and Herzegovina / 64 ii IV CHAPTER II The Unmaking -

S/1994/674/Annex VIII Page 311 Operated by Military Police Units from Drvar. It Is Unclear If Guards from Camp Kozile Were Also

S/1994/674/Annex VIII Page 311 operated by military police units from Drvar. It is unclear if guards from camp Kozile were also transferred here for duty. 4101 / 2580 . Prekaja : The existence of this detention facility has not been corroborated by multiple sources. Reportedly just near Drvar, in the village of Prekaja is an alleged Serb controlled concentration camp. 4102 / Allegedly operated by extremists, the interns were purportedly tortured and killed at this camp. 4103 / 2581 . Titov Drvar : The existence of this detention facility has been corroborated by a neutral source, namely Medecins Sans Frontieres. Medecins Sans Frontieres reportedly acquired evidence of two Serb controlled concentration camps in Titov Drvar. 4104 / The French source interviewed several Muslim refugees from the town of Kozarac who had been interned in the Serb controlled camps. 4105 / The French agency reported that more than half of the refugees had reportedly been tortured. 4106 / 2582 . Drvar Prison : (The existence of this detention facility has not been corroborated by multiple sources). Another report alleges the existence of a Bosnian Serb controlled camp at the prison. 4107 / This location was identified as of May 1993. 4108 / The source, however, did not provide additional information regarding either operation or prisoner identification. 78. Tomislavgrad 2583 . This municipality is located in central BiH, bordering Croatia to the west. According to the 1991 Yugoslav census, the county had a population of 29,261. Croats constituted 86.6 per cent of the population, Muslims 10.8 per cent, Serbs 1.5 per cent, and the remaining 1.1 per cent were classified as "other". -

Paper Download (410996 Bytes)

Heroes of yesterday, war criminals of today: the Serbian paramilitary units fifteen years after the armed conflict of former Yugoslavia Keywords: paramilitary, Serbia, war crimes, media, former Yugoslavia, veterans Abstract: The aim of the paper is to describe the transformation, primarily through the medias, the image of the Serbian paramilitary unit members employed during the armed conflict of the 90es in the period of the decomposition of the former Yugoslavia. At the beginning, represented as „heroes‟, „saviors‟, „protectors‟ of the „serbianhood‟ (srpstvo), ever present main figures of the public life – their public image has gone through a couple of change. Once they were the role models for the young generation, only after the fall of the regime (2000) their involvement in war crimes, mass rape, looting and genocide attained Serbia. Several landmark trials offered a glimpse into their role during the series of the conflicts. Once warlords, with a status of pop icons, the embodiment of mythical warriors and epic bandits, they are no more the living archetypes of collective remembrance, although their responsibility remain unquestionable for a part of the contemporary society. * The paper‟s aim is to describe the transformation, primarily through the medias, of the image of the Serbian paramilitary unit members employed during the armed conflict of the 90es in the period of the decomposition of the former Yugoslavia. At the beginning, represented as „heroes‟, „saviors‟, „protectors‟ of the „serbianhood‟, ever present as main figures of the public life – their public image has gone through a couple of change. Once they were the role models for the young generation, only after the fall of the Milošević regime (2000) their involvement in war crimes, mass rape, looting and genocide attained Serbia. -

CHAPTER XI - General Conclusions

CHAPTER XI - General Conclusions Chapter XI General Conclusions This Report reflects the findings of theIndependent International Commission of Inqui- ry on the Sufferings of All Peoples in the Srebrenica Region between 1992 and 1995, whose work was authorized by, but independent of, Republika Srpska with the mandate of addressing critical issues in connection with the popular perceptions surrounding Srebrenica during the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Commission is independent in that it does not reflect the joint efforts of any particular institution, be it governmental, academic, legal, or any other form of NGO. Members were selected by virtue of their particular expertise in relevant disciplines and are solely responsible for their contributions to the overall Report. Toward this end, the international members worked independently, individually or with their team, to examine the available facts surrounding the events that occurred in the Srebrenica region during the war years. All avenues of data and information were pursued in order to gather relevant material, despite the fact that some avenues of inquiry were not forthcoming. Nonetheless, best efforts were made by each member in his or her pursuit of providing a comprehensive examination of the facts relevant to the Commission mandate. The multidisciplinary composition of the Commission resulted in different approaches and research methodologies. In addition to published sources and reference works, docu- ments presented before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia during various court proceedings were also largely used. During the reconstruction of the events related to July 11, 1995, primary sources were used to the greatest extent, while secondary sources were used only in those cases when there were no primary sources available. -

ICTY Prosecutor V. Momcilo Perisic

International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Case: IT-00-39-T Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Date: 27 September 2006 UNITED Committed in the Territory of the NATIONS Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English TRIALU CHAMBER I Before: Judge Alphons Orie, Presiding Judge Joaquín Martín Canivell Judge Claude Hanoteau Registrar: Mr Hans Holthuis Judgement of: 27 September 2006 PROSECUTOR v. MOMČILO KRAJIŠNIK _________________________________________________________________________ JUDGEMENT _________________________________________________________________________ OfficeU of the Prosecutor Mr Mark Harmon Mr Alan Tieger Mr Stephen Margetts Mr Fergal Gaynor Ms Carolyn Edgerton Ms Katrina Gustafson DefenceU Counsel Mr Nicholas Stewart, QC Mr David Josse Prosecutor v. Momčilo Krajišnik Preliminary ContentsU General abbreviations 6 1. Introduction and overview 9 1.1 The Accused 9 1.2 Indictment 10 1.3 Bosnia-Herzegovina: geography, population, history 12 1.4 Structure of judgement 14 2. Political precursors 16 2.1 Political developments, 1990 to early 1991 16 2.1.1 Creation of the SDS 16 2.1.2 Division of power among the coalition parties 17 2.2 Arming and mobilization of population 19 2.3 State of fear 24 2.4 Creation of Serb autonomous regions and districts 26 2.5 Creation of Bosnian-Serb Assembly 31 2.6 SDS Instructions of 19 December 1991 36 2.7 Proclamation of Bosnian-Serb Republic 43 2.8 Establishment of Bosnian-Serb Republic 50 3. Administration of Bosnian-Serb Republic 54 3.1 Bosnian-Serb -

Judgement Summary Trial Chamber

UNITED NATIONS International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals The International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (“Mechanism”) was established on 22 December 2010 by the United Nations Security Council to continue the jurisdiction, rights, obligations and essential functions of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (“ICTR”) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (“ICTY”) which closed in 2015 and 2017, respectively. JUDGEMENT SUMMARY TRIAL CHAMBER (Exclusively for the use of the media. Not an official document) The Hague, 30 June 2021 Judgement Summary for Prosecutor v. Jovica Stanišić and Franko Simatović Please find below the summary of the Judgement read out today by Judge Burton Hall 1. The Trial Chamber is sitting today to pronounce its Judgement in the case of Prosecutor v. Jovica Stanišić and Franko Simatović. I will read a summary of the Judgement, highlighting the Trial Chamber’s key findings. The written reasons for the Judgement will follow as soon as possible after the conclusion of the editorial process. This procedure is provided for in Rules 122(A) and (C). The written Judgement, when filed, will be the only authoritative version of the Judgement. 2. Before addressing the merits, I would like to express appreciation to those who have assisted us in bringing this case - which is being tried for a second time - to a close. We have received excellent support throughout this case from our court officers and reporters and the staff in language services, information technology, witness support and protection, detention, general services, and security. Your work was never easy and was made even more difficult as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Former Yugoslavia

Serbia and Montenegro Page 1 of 39 June 1995 Vol. 7, No. 10 FORMER YUGOSLAVIA WAR CRIMES TRIALS IN THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA INTRODUCTION By early 1995, the international tribunal established by the United Nations to adjudicate war crimes and crimes against humanity in the former Yugoslavia1 had indicted twenty-two individuals for serious violations of humanitarian law, including the crime of genocide.2 Yet despite these indictments, cooperation with international efforts to achieve justice in the former Yugoslavia have been obstructed, particularly by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e., Serbia and Montenegro). Serbian, Yugoslav, Croatian and Bosnian authorities all claim that they will try members of their own forces for human rights violations, but few such trials have taken place. Those trials that have taken place are rarely prosecuted properly. For example, in a recent trial in Serbia proper against Du_an Vukovi, a Serbian paramilitary responsible for gross human rights violations in Bosnia-Hercegovina, the prosecution's line of questioning did more to assist the defense than its own side. Domestic trials of alleged war criminals are politicized and due process rights are not always respected. This report demonstrates the limitations of local war crimes prosecutions in Croatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, thereby illustrating why the work of the international war crimes tribunal is so necessary, particularly for the indictment and prosecution of high-ranking political and military officials bearing command responsibility for the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes by local authorities and soldiers. However, in order for justice to be served, the international community must retain some leverage with which to pressure governments or authorities to extradite those indicted by the tribunal, preferably through the imposition or retention of sanctions against governments that refuse to cooperate with international efforts to ensure accountability for egregious crimes. -

Dosije: JNA U Ratovima U Hrvatskoj I Bih Dossier: the JNA in the Wars In

Dossier:Dosije: The JNA inu ratovima the Wars inu CroatiaHrvatskoj and i BiHBiH ISBN 978-86-7932-090-2 978-86-7932-091-9 Dossier: The JNA in the Wars 1 in Croatia and BiH Belgrade, Dossier: The JNA in the Wars in CroatiaJune and BiH2018 2 Dossier: The JNA in the Wars in Croatia and BiH Contents ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SUMMARY....................................................................................................................................................................... 7 I. THE JNA WITHIN THE SFRY ARMED FORCES ............................................................................................. 8 II. SHIFT IN THE JNA’S OBJECTIVES AND TASKS IN THE COURSE OF THE CONFLICT IN CROATIA.......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 i. Political Crisis in the SFRY and the SFRY Presidency Crisis ................................................................. 10 ii. Political Situation in Croatia – Emergence of the Republic of Serbian Krajina ............................... 13 iii. First Phase of JNA Involvement in the Conflict in Croatia ................................................................. 14 iv. Second Phase of JNA Involvement in the Conflict in Croatia ............................................................. 15 v. Decision to -

The International Criminal Tribunal

MICT-13-55-A 2313 A2313 - A2081 23 December 2016 SF THE MECHANISM FOR INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNALS No. MICT-13-55-A IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron Judge William Hussein Sekule Judge Vagn Prusse Joensen Judge Jose Ricardo de Prada Solaesa Judge Graciela Susana Gatti Santana Registrar: Mr John Hocking Date Filed: 23 December 2016 THE PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC Revised Public Redacted Version RADOVAN KARADZIC’S APPEAL BRIEF ________________________________________________________________________ Office of the Prosecutor: Laurel Baig Barbara Goy Katrina Gustafson Counsel for Radovan Karadzic Peter Robinson Kate Gibson No. MICT-13-55-A 2312 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 II. THE TRIAL WAS UNFAIR.......................................................................................... 5 1. The Trial Chamber violated President Karadzic’s right to self-representation by requiring him to be questioned by counsel when testifying ............................................. 5 2. The Trial Chamber erred in conducting a site visit in President Karadzic’s absence... 9 3-5. The Trial Chamber erred in convicting President Karadzic on Counts Four, Seven, and Eleven where the Indictment was defective ............................................................. 13 6. The Trial Chamber’s failure to limit the scope of the trial and remedy the Prosecution’s disclosure violations made the trial unfair ..............................................