Paper Download (410996 Bytes)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis Pronk, 16 July 2009, the ICTY and the People from T…

The ICTY and the people from the former Yugoslavia A reserved relationship. An evaluation of the outreach efforts of the International Tribunal for the prosecution of persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 (ICTY). By: Erik Pronk Tutor: Bob de Graaff Student number: 0162205 Study: International Relations in Historical Perspective Preface ..................................................................................................................................3 Introduction..........................................................................................................................4 The (impact of the) war in the former Yugoslavia................................................................8 The establishment of the ICTY ..........................................................................................15 Chapter 1: The ICTY 1993-1999 .......................................................................................17 The ICTY pre-operational (1993-1994).............................................................................17 The Goldstone era (1994-1996) ........................................................................................19 The Louise Arbour Era (1996-1999).................................................................................28 Chapter 2 Criticism from the Balkans, 1993-1999............................................................34 The role of the media........................................................................................................37 -

Cßr£ S1ÍU2Y M Life ;-I;

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository p fr-; C ß R £ S1ÍU2Y lifem ; - i ; : : ... _ ...._ _ .... • Ûfc 1î A mm V . W-. V W - W - W__ - W . • i.r- / ■ m . m . ,l.m . İr'4 k W « - Xi û V T k € t> \5 0 Q I3 f? 3 -;-rv, 'CC/f • ww--wW- ; -w W “V YUGOSLAVIA: A CASE STUDY IN CONFLICT AND DISINTEGRATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES BILKENT UNIVERSITY MEVLUT KATIK i ' In Partial Fulfillment iff the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts February 1994 /at jf-'t. "•* 13 <5 ' K İ8 133(, £>02216$ Approved by the Institute of Economics and Socjal Sciences I certify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate,in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. Prof.Dr.Ali Karaosmanoglu I certify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. A j ua. Asst.Prof. Dr. Nur Bilge Criss I certify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations. Asst.Prof.Dr.Ali Fuat Borovali ÖZET Eski Yugoslavya buğun uluslararasi politikanin odak noktalarindan biri haline gelmiştir. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Iii Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Eu Treaty

19.6.2007EN Official Journal of the European Union L 157/23 III (Acts adopted under the EU Treaty) ACTS ADOPTED UNDER TITLE V OF THE EU TREATY COUNCIL DECISION 2007/423/CFSP of 18 June 2007 implementing Common Position 2004/293/CFSP renewing measures in support of the effective implementation of the mandate of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, crimes for which they have been indicted by the ICTY, or who are otherwise acting in a manner which could obstruct the ICTY's effective implementation of its mandate, should be listed. Having regard to Council Common Position 2004/293/CFSP (1), and in particular Article 2 thereof in conjunction with Article 23(2) of the Treaty on European Union, (4) The list contained in the Annex to Common Position 2004/293/CFSP should be amended accordingly, Whereas: HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 (1) By Common Position 2004/293/CFSP the Council The list of persons set out in the Annex to Common Position adopted measures to prevent the entry into, or transit 2004/293/CFSP shall be replaced by the list set out in the through, the territories of Member States of individuals Annex to this Decision. who are engaged in activities which help persons at large continue to evade justice for crimes for which they have Article 2 been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), or who are otherwise This Decision shall take effect on the date of its adoption. acting in a manner which could obstruct the ICTY's effective implementation of its mandate. -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Case: Branko Grujić Et Al – 'Zvornik' War Crimes Chamber Belgrade District Court, Republic of Serbia Case Number: KV.5/05

Case: Branko Grujić et al – ‘Zvornik’ War Crimes Chamber Belgrade District Court, Republic of Serbia Case number: KV.5/05 Trial Chamber: Tatjana Vuković, Trial Chamber President, Vesko Krstajić, Judge, Trial Chamber Member, Olivera Anđelković, Judge, Trial Chamber Member War Crimes Prosecutor: Milan Petrović Accused: Branko Grujić, Branko Popović, Dragan Slavković a.k.a. Toro, Ivan Korać a.k.a. Zoks, Siniša Filipović a.k.a. Lopov, and Dragutin Dragićević a.k.a. Bosanac Report: Nataša Kandić, Executive Director of the Humanitarian Law Centre (HLC), and Dragoljub Todorović, Attorney, victims representatives 30 November 2005 Branko Popović’s defence Branko Popović, who used the alias of Marko Pavlović, was in charge of the Zvornik TO Staff. He was born and lived in Sombor in Serbia. Besides working for the socially-owned company Sunce, he had a firm of his own and helped Serb refugees from Croatia through the „Krajina‟ association. The first person from Zvornik he met, through Rade Kostić, the deputy minister of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Serb Krajina, was witness K. The meetings in Mali Zvornik in Serbia Shortly before the war, that is, at the end of March 1992, the SDS president in Zvornik invited Popović to a meeting at the Hotel Jezero in Mali Zvornik with volunteers from Serbia who wanted to help and to give an „inspiration to the Serb people should it come to war.‟ The accused said that it was there that he met Vojin Vučković a.k.a. Žuća, a man named Rankić, a man named Bogdanović, and Žuća‟s brother Dušan Vučković a.k.a. -

Die Situation Der Medien in Serbien

7Christova-Förger:Layout 1 25.03.09 15:38 Seite 95 95 DIE SITUATION DER MEDIEN IN SERBIEN Christiana Christova / Dirk Förger Dr. Christiana Christova ist Assis - tentin des Medien- „Medien haben die Möglichkeit, programms Südost- europa der Konrad- sich an der Suche nach der Wahrheit zu beteiligen Adenauer-Stiftung und einen Teil am Versöhnungsprozess in Sofia/Bulgarien. der Menschen zu übernehmen.”1 EINLEITUNG Die Auflösung des ehemaligen Jugoslawien führte über eine Reihe von Kriegen und Abspaltungen. Eckdaten dabei waren die Konflikte um Slowenien (1991), Kroatien (1991–1995) und Bosnien-Herzegowina (1992–1995). 1993 wurde die Un- abhängigkeit Mazedoniens anerkannt, 2006 erhielt Montene- gro seine Eigenständigkeit. Im Februar 2008 erklärte schließ- Dr. Dirk Förger ist lich der Kosovo seine Unabhängigkeit. Der Zerfallsprozess Journalist und Lei- ter des Medienpro- war von politischen Systemänderungen begleitet: Während gramms Südosteu- Jugoslawien bis zur Absetzung Miloševićs 2000 ein autoritär ropa der Konrad- geführtes Regime hatte, setzte mit den Wahlen von Vojislav Adenauer-Stiftung mit Sitz in Sofia/ Kostunica zum Präsidenten und insbesondere von Zoran Đin- Bulgarien. dić zum Ministerpräsidenten eine liberal-demokratische Ent- wicklung ein. Diese verläuft mal positiv, mal erleidet sie schwere Rückschläge wie durch die Ermordung Đindićs 2003. Immerhin steuert der im Mai 2008 wieder gewählte Präsident Serbiens, Boris Tadic, das Land auf einen proeuro- päischen Kurs und hat den EU-Beitritt zum obersten Ziel er- klärt. 1 | Veran Matic, Direktor von B92, im der Sendung „kulturplatz”, 27.08.08 7Christova-Förger:Layout 1 25.03.09 15:38 Seite 96 96 Die Lage der Medien in Die Veränderungen auf politischer Ebene wirkten sich natür- Serbien ist trotz positi- lich auch stark auf die Medienlandschaft aus. -

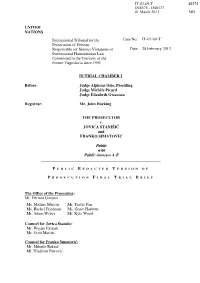

Public Redacted Version of Prosecution Final Trial Brief

IT-03-69-T 48575 D48575 - D48137 01 March 2013 MB UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-03-69-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 28 February 2013 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 IN TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Alphons Orie, Presiding Judge Michèle Picard Judge Elizabeth Gwaunza Registrar: Mr. John Hocking THE PROSECUTOR v. JOVICA STANIŠIĆ and FRANKO SIMATOVIĆ Public with Public Annexes A-E P U B L I C R E D A C T E D V E R S I O N O F P ROSECUTION F I N A L T R I A L B RIEF The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Dermot Groome Ms. Maxine Marcus Mr. Travis Farr Ms. Rachel Friedman Ms. Grace Harbour Mr. Adam Weber Mr. Kyle Wood Counsel for Jovica Stani{i}: Mr. Wayne Jordash Mr. Scott Martin Counsel for Franko Simatovi}: Mr. Mihajlo Bakrač Mr. Vladimir Petrovi} 48574 THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA IT-03-69-T THE PROSECUTOR v. JOVICA STANIŠIĆ and FRANKO SIMATOVIĆ Public with Public Annexes A-E P U B L I C R E D A C T E D V E R S I O N O F P ROSECUTION F I N A L T R I A L B RIEF On 14 December 2012 the Prosecution filed its Final Trial Brief and five annexes ∗ confidentially. The following is a public redacted copy of this filing. Pursuant to Rule 86 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence the Prosecution submits its Final Trial Brief with the following Annexes: i. -

Serbia in 2001 Under the Spotlight

1 Human Rights in Transition – Serbia 2001 Introduction The situation of human rights in Serbia was largely influenced by the foregoing circumstances. Although the severe repression characteristic especially of the last two years of Milosevic’s rule was gone, there were no conditions in place for dealing with the problems accumulated during the previous decade. All the mechanisms necessary to ensure the exercise of human rights - from the judiciary to the police, remained unchanged. However, the major concern of citizens is the mere existential survival and personal security. Furthermore, the general atmosphere in the society was just as xenophobic and intolerant as before. The identity crisis of the Serb people and of all minorities living in Serbia continued. If anything, it deepened and the relationship between the state and its citizens became seriously jeopardized by the problem of Serbia’s undefined borders. The crisis was manifest with regard to certain minorities such as Vlachs who were believed to have been successfully assimilated. This false belief was partly due to the fact that neighbouring Romania had been in a far worse situation than Yugoslavia during the past fifty years. In considerably changed situation in Romania and Serbia Vlachs are now undergoing the process of self identification though still unclear whether they would choose to call themselves Vlachs or Romanians-Vlachs. Considering that the international factor has become the main generator of change in Serbia, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia believes that an accurate picture of the situation in Serbia is absolutely necessary. It is essential to establish the differences between Belgrade and the rest of Serbia, taking into account its internal diversities. -

La Garde Des Volontaires Serbes / Les Tigres D'arkan

Serbie 2 octobre 2017 La Garde des volontaires serbes / Les Tigres d’Arkan Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Serbie : la Garde des volontaires serbes Table des matières 1. Historique de la Garde des volontaires serbes ........................................................ 3 1.1. Genèse ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Organisation et fonctionnement ..................................................................... 4 1.3. -

Décision Relative À La Requête De L'accusation Aux Fins De Dresser Le Constat Judiciaire De Faits Relatifs À L'affaire Krajisnik

IT-03-67-T p.48378 NATIONS o ~ ~ 31 g -.D ~s 3b 1 UNIES J ~ JUL-j ~D)D Tribunal international chargé de Affaire n° : IT-03-67-T poursuivre les personnes présumées responsables de violations graves du Date: 23 juillet 2010 droit international humanitaire commises sur le territoire de l'ex Original: FRANÇAIS Yougoslavie depuis 1991 LA CHAMBRE DE PREMIÈRE INSTANCE III Composée comme suit: M.le Juge Jean-Claude Antonetti, Président M.le Juge Frederik Harhoff Mme. le Juge Flavia Lattanzi Assisté de: M. John Hocking, greffier Décision rendue le: 23 juillet 2010 LE PROCUREUR cl VOJISLAV SESELJ DOCUMENT PUBLIC A VEC ANNEXE DÉCISION RELATIVE À LA REQUÊTE DE L'ACCUSATION AUX FINS DE DRESSER LE CONSTAT JUDICIAIRE DE FAITS RELATIFS À L'AFFAIRE KRAJISNIK Le Bureau du Procureur M. Mathias Marcussen L'Accusé Vojislav Seselj IT-03-67-T p.48377 1. INTRODUCTION 1. La Chambre de première instance III (<< Chamb re ») du Tribunal international chargé de poursuivre les personnes présumées responsables de violations graves du droit international humanitaire commises sur le territoire de l'ex-Yougoslavie depuis 1991 (<< Tribunal ») est saisie d'une requête aux fins de dresser le constat judiciaire de faits admis dans l'affaire Le Procureur cl Momcilo Krajisnik, en application de l'article 94(B) du Règlement de procédure et de preuve (<< Règl ement »), enregistrée par le Bureau du Procureur (<< Ac cusation ») le 29 avril 2010 (<< Requête») 1. H. RAPPEL DE LA PROCÉDURE 2. Le 29 avril 2010, l'Accusation déposait sa Requête par laquelle elle demandait que soit dressé le constat judiciaire de 194 faits tirés du jugement rendu dans l'affaire Krajisnik (<< Jugement ») 2. -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina