The Pleasures of Architecture”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Architecture Award Winners 1981 – 2019

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2019 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 81 2019 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Yagan Square (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Lyons in collaboration with Iredale Pedersen Hook and landscape architects ASPECT Studios COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Dangrove (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Breathe Architecture Private Women’s Club (VIC) National Award for Commercial Architecture Kerstin Thompson Architects EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Primary School (NSW) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture BVN Braemar College Stage 1, Middle School National Award for Educational Architecture Hayball Adelaide Botanic High School (SA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Cox Architecture and DesignInc QUT Creative Industries Precinct 2 (QLD) National Commendation for Educational Architecture KIRK and HASSELL (Architects in Association) ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Sails in the Desert (NT) National Award for Enduring Architecture Cox Architecture HERITAGE Premier Mill Hotel (WA) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Spaceagency architects Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Heritage Breathe Architecture Flinders Street Station Façade Strengthening & Conservation National Commendation for Heritage (VIC) Lovell Chen Sacred Heart Building Abbotsford Convent Foundation -

Company Profile Education

COMPANY PROFILE EDUCATION Marshall Day Acoustics - Education 1 WHO IS MARSHALL DAY ACOUSTICS? Marshall Day Acoustics is one of the world’s leading firms of acoustic consultants, providing the highest standard of architectural and environmental acoustic consulting to our clients. For over 30 years, we have been providing innovative acoustic designs on major projects in over 15 countries and employ over 85 professional staff in offices in Australia, New Zealand, China, Hong Kong, and France. As one of the largest acoustic engineering firms worldwide, we are able to provide our clients with the greatest range and depth of experience and expertise available. Our strength in acoustic design comes from the diversity of our team members who have been drawn from engineering, architectural, musical and academic backgrounds, with one common focus; to provide innovative acoustic designs of the highest standard. From concert halls to wind farms and everything in between, we have experts in every field of acoustics who have the specialist knowledge required to deliver quality project outcomes. “I regard the acoustic designs of Marshall Day Acoustics to be amongst the finest and probably the most innovative in the world” Dr Anders Gade, Associate Professor Technical University of Denmark Marshall Day Acoustics - Education 3 A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH We have a collaborative approach to design and work as part of an integrated team with the client, architect and other consultants. We do not specify acoustic performance that “must” be achieved but instead we work with the project team to develop acoustic criteria and treatment that meets the desired project outcomes, whatever they may be. -

'Quilled on the Cann': Alexander Hart, Scottish Cabinet Maker, Radical

‘QUILLED ON THE CANN’ ALEXANDER HART, SCOTTISH CABINET MAKER, RADICAL AND CONVICT John Hawkins A British Government at war with Revolutionary and Republican France was fully aware of the dangers of civil unrest amongst the working classes in Scotland for Thomas Paine’s Republican tract The Rights of Man was widely read by a particularly literate artisan class. The convict settlement at Botany Bay had already been the recipient of three ‘Scottish martyrs’, the Reverend Thomas Palmer, William Skirving and Thomas Muir, tried in 1793 for seeking an independent Scottish republic or democracy, thereby forcing the Scottish Radical movement underground. The onset of the Industrial Revolution, and the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars placed the Scottish weavers, the so called ‘aristocrats’ of labour, in a difficult position for as demand for cloth slumped their wages plummeted. As a result, the year 1819 saw a series of Radical protest meetings in west and central Scotland, where many thousands obeyed the order for a general strike, the first incidence of mass industrial action in Britain. The British Government employed spies to infiltrate these organisations, and British troops were aware of a Radical armed uprising under Andrew Hardie, a Glasgow weaver, who led a group of twenty five Radicals armed with pikes in the direction of the Carron ironworks, in the hope of gaining converts and more powerful weapons. They were joined at Condorrat by another group under John Baird, also a weaver, only to be intercepted at Bonnemuir, where after a fight twenty one Radicals were arrested and imprisoned in Stirling Castle. -

Alastair Hall Swayn 1944–2016 Alastair Swayn, Who Died on 4

Alastair Hall Swayn 1944–2016 Alastair Swayn, who died on 4 August 2016 of brain cancer, left his distinctive mark on Australia’s national capital, Canberra, through his many striking and innovative public and private buildings designed in his role as director of Daryl Jackson Alastair Swayn Architects. As the inaugural Australian Capital Territory Government Architect, Alastair ensured that design and contemporary thinking was at the fore of decision-making in creating Canberra as a small ‘new world city’. As Professorial fellow in Architecture of the University of Canberra he was widely recognised as a distinguished teacher and mentor. The boldness and imaginativeness of his vision are reflected in some of the city’s most distinctive buildings such as the Brindabella Business Park, the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at the Australian National University, the Singapore High Commission, and many others. Alastair Hall Swayn was born on 8 December 1944 in the small Scottish coal mining port of Methil in Fife. With its industrial maritime feel, the town marked the start of Alastair’s lifelong love of ships and industrial architecture. In 1948 Alastair and his parents moved to Liverpool, where his father, Frank, managed the British Cunard Line’s laundry service. As a young boy, Alastair would accompany him aboard some of the line’s famous ships such as the Mauretania and Caroni. The Art Deco interiors of these and other luxury liners inspired an abiding interest in the form. At Merchant Taylors, Alastair showed a flair for architectural drawing, and he went on to study architecture at Liverpool Polytech. -

'Paper Houses'

‘Paper houses’ John Macarthur and the 30-year design process of Camden Park Volume 2: appendices Scott Ethan Hill A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney Sydney, Australia 10th August, 2016 (c) Scott Hill. All rights reserved Appendices 1 Bibliography 2 2 Catalogue of architectural drawings in the Mitchell Library 20 (Macarthur Papers) and the Camden Park archive Notes as to the contents of the papers, their dating, and a revised catalogue created for this dissertation. 3 A Macarthur design and building chronology: 1790 – 1835 146 4 A House in Turmoil: Just who slept where at Elizabeth Farm? 170 A resource document drawn from the primary sources 1826 – 1834 5 ‘Small town boy’: An expanded biographical study of the early 181 life and career of Henry Kitchen prior to his employment by John Macarthur. 6 The last will and testament of Henry Kitchen Snr, 1804 223 7 The last will and testament of Mary Kitchen, 1816 235 8 “Notwithstanding the bad times…”: An expanded biographical 242 study of Henry Cooper’s career after 1827, his departure from the colony and reported death. 9 The ledger of John Verge: 1830-1842: sections related to the 261 Macarthurs transcribed from the ledger held in the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, A 3045. 1 1 Bibliography A ACKERMANN, JAMES (1990), The villa: form and ideology of country houses. London, Thames & Hudson. ADAMS, GEORGE (1803), Geometrical and Graphical Essays Containing a General Description of the of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling, and perspective; the fourth edition, corrected and enlarged by William Jones, F. -

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture The search for beauty, meaning and freedom in a harsh climate Boston University Sydney Centre Spring Semester 2015 Course Co-ordinator Peter Barnes [email protected] 0407 883 332 Course Description The course provides an introduction to the history of art and architectural practice in Australia. Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuing art tradition (indigenous Australian art) and one of the youngest national art traditions (encompassing Colonial art, modern art and the art of today). This rich and diverse history is full of fascinating characters and hard won aesthetic achievements. The lecture series is structured to introduce a number of key artists and their work, to place them in a historical context and to consider a range of themes (landscape, urbanism, abstraction, the noble savage, modernism, etc.) and issues (gender, power, freedom, identity, sexuality, autonomy, place etc.) prompted by the work. Course Format The course combines in-class lectures employing a variety of media with group discussions and a number of field trips. The aim is to provide students with a general understanding of a series of major achievements in Australian art and its social and geographic context. Students should also gain the skills and confidence to observe, describe and discuss works of art. Course Outline Week 1 Session 1 Introduction to Course Introduction to Topic a. Artists – The Port Jackson Painter, Joseph Lycett, Tommy McCrae, John Glover, Augustus Earle, Sydney Parkinson, Conrad Martens b. Readings – both readers are important short texts. It is compulsory to read them. They will be discussed in class and you will need to be prepared to contribute your thoughts and opinions. -

Break out Your Black Turtle Neck Jumper: It’S Time to Talk About Design

Break out your black turtle neck jumper: it’s time to talk about design ADAM DAVIES, PRINCIPAL 19 September 2017 Some people think design means how it looks. But of course, if you dig “deeper, it’s really how it works. - Steve Jobs, former CEO, Apple For places to be well-used and well-loved, they must be safe, comfortable, varied and attractive. They also need to be distinctive and offer variety, choice and fun - Urban “Design Compendium Randwick Health and Education Super Precinct Positioning Strategy, HASSELL, 2016, Sydney UK Design Renaissance 1999 The majority of new developments remain poorly designed, with public realm and buildings of low“ quality… too many housing projects… lack the core social and commercial institutions that sustain urban life and a sense of place and beauty… The Urban Renaissance Task Force, 1999. CABE COMMISSION FOR ARCHITECTURE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT CABE DESIGN VALUE EXCHANGE VALUE IMAGE VALUE > Book value > Brand awareness > Return on capital > Prestige > Rental Yield > Identity > Design excellence > Public relations SOCIAL VALUE ENVIRONMENTAL > Place making > Sense of community TYPES OF > Environmental impact > Civic pride VALUE > Whole-life-value > Neighbourly behaviour > Ecological footprint > Safety and security > Inclusiveness USER VALUE CULTURAL VALUE > User satisfaction > Contribution the city and society > Teamwork > Relationship to location and context > Productivity > Symbolism > Profitability > Inspiration > Retail footfall > Aesthetics > Educational attainment Design value RETURN ON INVESTMENT -

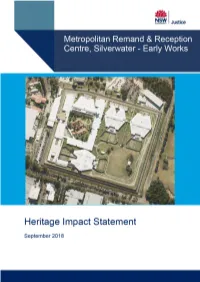

Silverwater Correctional Complex Upgrade Early Works

THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Table of Contents Contents Heritage Impact Statement ........................................................................................................... 1 Document Control .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Project Overview ............................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 The Site ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Heritage Context ................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Silverwater Correctional Complex CMP ................................................................................ 8 2. History ............................................................................................................................ 10 3. Site and Building Descriptions ..................................................................................... 13 3.1 Context within the Site ........................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Current Use ........................................................................................................................ 13 4. Significance -

Australian National University Acton Campus — Site Inventory

Australian National University Acton Campus — Site Inventory Study Item/ Area School of Music Acton Campus Precinct BALDESSIN Precinct Building Nos. & Names 100 (Canberra School of Music), 121 (Peter Karmel Building), 105B (National Institute of the Arts (NITA) (Administration), 123 (Section 16/28, Canberra City) Figure 1: Location of study area within the ANU Acton Campus site. Heritage Ranking School of Music—High—Meets the criteria for Commonwealth Heritage List Peter Karmel Building—Neutral—Does not meet criteria for Commonwealth Heritage List Heritage Listing The School of Music is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL). Condition—Date The condition noted here is at December 2011. The extant buildings and trees of the Canberra School of Music continue to be well maintained for academic study and research and are in good condition. Relevant Documentation A (draft) Heritage Management Plan was prepared for the School of Music in 2010 by the ANU Heritage Office. 1 ANU Acton Campus — Site Inventory — School of Music (100, 121, 105b & 123) Australian National University Acton Campus — Site Inventory Context of the Buildings Figure 2: Canberra School of Music in its setting of the Baldessin Figure 3: Canberra School of Music in its setting off Childers Street near Precinct. the School of Art (Building 105). Brief Historical Overview The idea for a school or Conservatorium of Music for Canberra can be traced back to the foundation years of the city. In March 1926 the Secretary of the Federal Capital Commission (FCC) CS Daley wrote to Dr WA Orchard, then Director of the NSW State Conservatorium of Music. -

08 November 1980, No 4

THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER 1980/4 November 1980 y ^^M MM mm •SHI THE AUSTRALIANA SOCIETY NEWSLETTER ISSN 0156.8019 The Australiana Society P.O. Box A 378 Sydney South NSW 2000 1980A November 1980 EDITORIAL: Museums and the Collector p.4 SOCIETY INFORMATION p.5 AUSTRALIANA NEWS p.6 AUSTRALIANA EXHIBITIONS p.10 OUR AUTHORS p.12 ARTICLES - Richard Phillips: The Bosleyware Pottery p.13 Michel Reymond: Land Records and Historic Buildings p.16 Ian Evans: A Portrait of Mrs. John Verge p.17 ANNUAL REPORT p.19 AUSTRALIANA BOOKS p.21 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS p.15 MEMBERSHIP FORM p.26 Registered for posting as a publication - category B Copyright 1980 The Australiana Society. All material written or illustrative, credited to an author, is copyright We gratefully record our thanks to James R. Lawson Pty. Ltd. for their generous donation which allows us to provide the photographs on the cover. production - aZhoJvt fie,yu>km (02) SU 1846 h Editorial MUSEUMS AND THE COLLECTOR "The editor cannot help concluding with a wish that the nobility and gentry would condescend to make their cabinets and collections accessible to the curious as is consistent with their safety." Thomas Martyn, 1766. Two hundred years after these words were written, economic pressures compelled the British aristocracy to open the doors of the great houses to the curious public. Today in Australia, while private collections are frequently available to the public through National Trust open days, exhibitions in public museums, or other means, the public collections of museums are all too rarely accessible. Museums draw too hard a line between those things which the public may see - the things on display - and those things the public may not see - the things in "storage". -

8. Australian Architecture 2

U3A, 2019 Dr Sharon Mosler 8. AUSTRALIAN COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE, 1788-1901 • Early convict colony, slow expansion 1788-1820s: Hawkesbury ’96,VDL • whaling & sealing, local agriculture; rum currency; two social classes • Rum Rebellion, 1809; Governor Bligh deposed; Gov Macquarie 1810 • Brisbane: pastoralism (Squatters) from 1822; currency lads and lasses • Gold Rush era, 1851-60s; great changes: economic, social, political • ‘Unlock the Land’ – Selection Acts 1860s – rural towns • New Unionism from 1888; Great Strikes 1990-94 • Gold Rush 1888-1900s, Q – WA; Depression of 1890s • Most urbanised country in the world 1900 (rural towns of 500+) • James Freeland, Architecture in Australia: a History, 1968 • Philip Goad, 150 years of Australian architecture, recent Here is an example of indigenous shelter (humpy?) at the time in cooler parts of NSW which the First Fleet settlers might have seen: Not all nomadic. Aboriginal tribes settled along the Murray River in Victoria and in WA coastal areas created houses with stone foundations. Half the population died of smallpox, other diseases. Evidence of these and their agricultural practices has been found: Bruce Pascoe, Dark emu, Paul Irish, Hidden in plain view. Because this land was invaded by the British in 1788 and became the British colony of New South Wales, the main British architectural styles at that time were ‘transported’ to the colony. This was Georgian architecture. Colonial rule continued on this continent until Federation in 1901, and British neo- classical and Gothic styles continued -

UQ Centenary Map: Improvement Around and Between Buildings

1910-1949 committee’s desires for the campus these words were well chosen. Effectively the architects had Smith building (administration, arts and law), the first two stories of the Duhlg library, and the Steele 1970 1980 architecture could contribute positive outdoor spaces to the campus, enhancing the relationship founding Hennessy Hennessy & Co plan. New thinking was required in facing up to a looming problem. NOTES dispensed with the strict quadrangle form favoured by the committee and replaced It with a grander building (chemistry) were the only buildings whose construction was completed at the opening. Two between buildings, their users and the campus landscape, The first project was the Therapies and The university sought further sites to develop on a campus that was already seen as filling up with 1 Pay! Venable Turner, Campus: An American Planning Tradition (Cambridge. Mass.: MIT Press, 1984). 167 \ 2 Malcolm CREATING THE GREAT COURT: The architectural and urban centerpiece of the St Lucia Campus - By the end of the 1960s, the perceived lack of space and the Increasing amount of vehicle traffic Through the 1980s the numbers of students attending university steadily grew and UQ continued its I Thornis, A Place of Light & Learning; The University of Queensland's First Seventy-Five Years (St. Lucia: University of Anatomy Building Stage 3. What might seem a relatively modest proposal today was actually a buildings. How could the university effectively plan for the development of its land without adversely UQ’s famous Great Court - clearly defines the University as a place. Its enclosing space makes a more open space.