Exploring the Topography, Activities and Dynamics of Early Medieval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

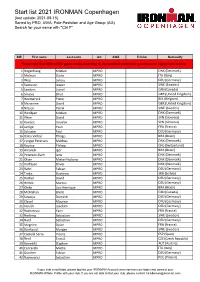

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Life and Cult of Cnut the Holy the First Royal Saint of Denmark

Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Kulturhistoriske studier i centralitet – Archaeological and Historical Studies in Centrality, vol. 4, 2019 Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense Bys Museer Syddansk Univeristetsforlag/University Press of Southern Denmark KING CNUT’S DONATION LETTER AND SETTLEMENT STRUCTURE IN DENMARK, 1085 – NEW PERSPECTIVES ON AN OLD DOCUMENT King Cnut’s donation letter and settle- ment structure in Denmark, 1085 – new perspectives on an old document By Jesper Hansen One of the most important sources to the history of donated to the Church of St Laurentius, the cathedral medieval Denmark is the donation letter of Cnut IV, church in Lund, and it represents the first written re- dated 21st of May 1085 and signed in Lund (fig. 1). cord of rural administration and fiscal rights in Den- This letter is a public affirmation of the royal gifts mark (Latin text, appendix 1). Cnut’s donation letter Skälshög, two hides. In Flädie, five this agreed-upon decree against the to the church in Lund and a half hides which Håkon gave to command of holy religion, he is to be the king. In Hilleshög, half a hide. In excommunicated upon the Return of (Dipl. Dan 1.2:21) Håstad, one hide. In Gärd. In Venestad, our Lord and to be consigned to eternal In the name of the indivisible Trinity, one hide. -

Verdens Bedste Forestilling'

LÆS KØB AVISEN ABONNEMENT POLITIKEN PLUS POLITIKEN BILLET ANNONCER MOBIL JOBZONEN WEEKLY OM POLITIKEN AVIS TIRSDAG 21. JUN SENESTE NYT: MOREN TIL DE VANRØGTEDE BØRN: BØRNENE ER HELE MIT LIV › TIP OS › FÅ POLITIKEN.DK SOM STARTSIDE KØBENHAVN LIGE NU: 16° › Vejret næste 10 døgn Skriv dit søgeord › Vejret i andre byer NYHEDER KULTUR SPORT DEBAT IBYEN TJEK TUREN GÅR TIL POLITIKEN TV FOTO BLOGS NEWS BAGSIDEN WM ABONNEMENT Biografen Koncerter Scene Udstillinger Café+Restaurant Natteliv Gadeplan Roskilde Jazzfestival Det sker IBYEN Find Restaurant Find Cafe 21 22 23 24 25 26 Søg på sted eller arrangement TIR ONS TOR FRE LØR SØN MEYERS KØKKEN:: DØDSMETALFESTIVAL: GUIDE: Alt andet end PLUS: ipal radio - rød, Meldt til politiet Helvedes hyggelig! musik på Roskilde sort eller hvid Pluspris 1.615 kr. SCENEN 19. JUN. 2011 KL. 10.00 Annoncer Instruktør laver teater med døve, blinde og udviklingshæmmede Hverdagens gemte personer indtager scenen i 'Verdens bedste forestilling'. SCENEN VERDENS BEDSTE FORESTILLING SENESTE SCENEN 21. JUN. KL. 15.01 Dato 18.-25. juni Vild med dans-vært Adresse Edisonsvej 10, Frederiksberg skal spille Evita Mere info www.gladteater.dk eller tlf. 27 22 16 84 21. JUN. KL. 10.00 Entré 85 kr. (grupper og unge: 65 kr.) 'Verdens bedste Sted Betty Nansen Teatret forestilling' er ægte freakshow SENESTE IBYEN 20. JUN. KL. 11.01 Hjørring Revyen FACEBOOK SEND PRINT vender tilbage efter fem års pause AF GHITA MAKOWSKA RASMUSSEN 20. JUN. KL. 11.01 Instruktøren Tue Biering har ikke bare hevet teatret ud i virkeligheden, Livsangst livredder men hevet virkelighedens gemte personer ind på teatret. -

DESIGN DESIGN Traditionel Auktion 899

DESIGN DESIGN Traditionel Auktion 899 AUKTION 10. december 2020 EFTERSYN Torsdag 26. november kl. 11 - 17 Fredag 27. november kl. 11 - 17 Lørdag 28. november kl. 11 - 16 Søndag 29. november kl. 11 - 16 Mandag 30. november kl. 11 - 17 eller efter aftale Bredgade 33 · 1260 København K · Tlf. +45 8818 1111 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.dk 899_design_s001-276.indd 1 12.11.2020 17.51 Vigtig information om auktionen og eftersynet COVID-19 har ændret meget i Danmark, og det gælder også hos Bruun Rasmussen. Vi følger myndig- hedernes retningslinjer og afholder den Traditionelle Auktion og det forudgående eftersyn ud fra visse restriktioner og forholdsregler. Oplev udvalget og byd med hjemmefra Sikkerheden for vores kunder er altafgørende, og vi anbefaler derfor, at flest muligt går på opdagelse i auktionens udbud via bruun-rasmussen.dk og auktionskatalogerne. Du kan også bestille en konditions- rapport eller kontakte en af vores eksperter, der kan fortælle dig mere om specifikke genstande. Vi anbefaler ligeledes, at flest muligt deltager i auktionen uden at møde op i auktionssalen. Du har flere muligheder for at følge auktionen og byde med hjemmefra: • Live-bidding: Byd med på hjemmesiden via direkte videotransmission fra auktionssalen. Klik på det orange ikon med teksten ”LIVE” ud for den pågældende auktion. • Telefonbud: Bliv ringet op under auktionen af en af vores medarbejdere, der byder for dig, mens du er i røret. Servicen kan bestilles på hjemmesiden eller via email til [email protected] indtil tre timer før auktionen. • Kommissionsbud: Afgiv et digitalt kommissionsbud senest 24 timer inden auktionen ud for det pågældende emne på hjemmesiden. -

Matr.-Nr. Gade-N R. Høide Over Dagligt Vande I Fod

I # DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK 130021681912 ft & 4 u / ♦ mm OVER * KJØBENHAVN OG PAA BENS GROND UDARBEIDET VED A. COLDING og J. T. SCHOVELIN, REVIDERET OG UDVIDET VED P. M. LINDBERG. oooo§§0<x>o ------------ KJØBENHAVN. I COMMISSION HOS C. A. REITZEL. LOUIS KLEINS BOGTRYKKERI. 1873. f S- & ir ' ■y. V ■ s , i » r r. f ± -- ;,5 -V * l/a et nøiagtigt og hensigtsmæssigt Nivellement over Kjøbenhavn og • ■ Christianshavn var meget ønskeligt før Udførelsen af de forestaaende communale Arbeider, og det navnlig maatte betragtes som den første og uundværligste Betingelse for Udarbeidclsen af en Cloakplan for Hoved- staden, blev det i Begyndelsen af 1855 besluttet, at et saadant skulde udføres. Vel existerede der et ældre Nivellement over Staden, der i sin Tid var udført for den kongelige Vandcommission af Captain Tuxen, men dette Nivellement var deels knyttet til sorte Streger, der vare malede paa Husene, deels til Bordursteen og andre endnu mindre faste Punkter, saa at det for Størstedelen enten var udslettet, forsvundet eller ubrugeligt ved at Stregerne vare overmalede, ornmalede eller flyttede, Steenbroen omlagt o. a. desl. Grundlaget for det nærværende Nivellement ere de i vedføiede Tabel opregnede 181 faste Punkter, som ere tilveiebragte ved at indmure Støbejerns Plader paa passende Steder i solide, grundmurede Bygninger, saaledes, at de bleve jevnt fordeelte over hele Staden. Den horizontale Overflade af Pladerne, der springe c. l l/4 Tomme frem fra Muren og ligge c. 21/4. Fod over Gaden, er dernæst bestemt i Forhold til daglig Vande i Havnen, og den saaledes fundne Høide, udtrykt i Fod med 2 Decimaler, er malet paa Muren ovenfor Pladen og er den samme Høide, som findes angivet i vedføiede Tabel. -

Food Lovers Guide to Copenhagen

Copenhagen Food lovers guide to Copenhagen 14 Feb 2017 11 2 3 5 6 Trine Nielsen jauntful.com/trinenielsencph 4 10 1 12 13 9 7 8 ©OpenStreetMap contributors, ©Mapbox, ©Foursquare Copenhagen Street Food 1 Malbeck Vinoteria 2 Toldboden 3 Pluto 4 Street Food Gathering Wine Bar Seafood Restaurant Food trucks with everything from One of my favorites in town. Great little Every Saturday and Sunday Toldboden One of my favorite restaurants in fish&chips, homemade tacos, Cuban and wine and tapas bar!! present one of the best and coolest Copenhagen. It’s informal, cosy and the Italian to burger, vegetarian, and thai. brunch buffets in Copenhagen. food is superb! Order the 12 course Very tasty & every stand must have a sharing menu – it’s worth it! 50kr dish Trangravsvej 14, Papirøen Birkegade 2 Nordre Toldbod 24, København K Borgergade 16, København copenhagenstreetfood.dk +45 32 21 52 15 malbeck.dk +45 33 93 07 60 toldboden.com +45 33 16 00 16 restaurantpluto.dk 20a Spisehus 5 Atelier September 6 Paté Paté 7 Sticks'n'Sushi 8 Restaurant Café Tapas Sushi Great food and wine to affordable A very small but cosy French café near Great cosy place at the Meatpacking This is the best place to get sushi in prices.Only serving charcuterie, meal & city center and it’s one of the most District with great food, wine and beer. Copenhagen – no doubt! They have fish of the day, and dessert. The food is popular places to have breakfast or lunch You can either have a whole meal or just restaurants several places in town. -

1946. Aikdfiiilelser, Teteoilliorte I Stalsléndfi I Juni Laanei, ; No. 6

U Udgivet ved Foranstaltning af Ministeriet for Handel, Industri og Søfart. 1946. AiKDfiiilelser, teteoilliorte i StalslÉndfi i Juni laanei, ; No. 6. KØBENHAVN. Carstens, Fritz, Deres Datters Ud Glas- & Staalkontoret ved H. Ro styr, 93. sted, 94. iA Anmeldelserne angaar følgende Firmaer- Carstensen & Co., 94. Hammerich, Asger, 94. Christensen & Berg, 96. Hammerich's, Asger, Eftf. vj Poul ) (De vedføjede Tal angiver Siderne, Christiani & Nielsen, 95. Lund, 94. hvor Anmeldelserne findes.) Christiansen, P., 96. Handels-Agentur <& Export Komp)agni Christiansen, Vilh , 97. Atlas v'j C. Højtved Pedersen og Christiansen, Vilh., forhen Georg C. Ejner Jørgensen, 98. Aalholm Fløde Is ved E. Johansen, 92. Møllers Efterfølgere, 97. Handelsfirmaet Dansk Textil -»Dan- jk Aasted Chocolate Machine Co., 96. Cotton Textile Company ved Frits tex( V. Henning Andersen, 94. sk Aatex ved Mogens Selby Hervard, 93. Kriiger, 98. Handelsfirmaet ^Echot ved Sigfred jk Aatex Velouriser ing s Industri ved Mo Dalsbo, Carl, & Co., 95. Reinhardt, 98. gens Hervard., 98. Dana-foto v. Orla Norup Nielsen, 93. Handelsfirmaet Knag vj L. P. Peter ik Achen s, P. H., Eftf. vj Eis Andersen Dansk Elektro Fysik ved Aage Chri sen, 92. og Orla Maare, 94. stiansen, 95. Handelsfirmaet Sveo ved K. Her L« •>Adento* ved Ib Olsen, 97. •»Dansk Fyrværkeri Fabrik<• ved Rich. mansen, 96. ik Aihk-Klinikudstyr ved H. J. Løve- Bagerskov, 96. ^Handelshuset Centrximf- vj L. Dænd- nov, 96. i Detlefsens Forlage, 95. ler, 95. Sk Aldako ved K. Hansen, 9&. Dorve, Kai, 95. ^ HandelshMset Christbro ved Thorkil k« >Al-Offset Reproduktion'L vi Firmaet Dyna-Start vj Svend Aage Thellefsen Christiansen og Povl Broust<, 95. -

City-Bike Maintenance and Availability

Project Number: 44-JSD-DPC3 City-Bike Maintenance and Availability An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Michael DiDonato Stephen Herbert Disha Vachhani Date: May 6, 2002 Professor James Demetry, Advisor Abstract This report analyzes the Copenhagen City-Bike Program and addresses the availability problems. We depict the inner workings of the program and its problems, focusing on possible causes. We include analyses of public bicycle systems throughout the world and the design rationale behind them. Our report also examines the technology underlying “smart-bike” systems, comparing the advantages and costs relative to coin deposit bikes. We conclude with recommendations on possible allocation of the City Bike Foundation’s resources to increase the quality of service to the community, while improving the publicity received by the city of Copenhagen. 1 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following for making this project successful. First, we thank WPI and the Interdisciplinary and Global Studies Division for providing off- campus project sites. By organizing this Copenhagen project, Tom Thomsen and Peder Pedersen provided us with unique personal experiences of culture and local customs. Our advisor, James Demetry, helped us considerably throughout the project. His suggestions gave us the motivation and encouragement to make this project successful and enjoyable. We thank Kent Ljungquist for guiding us through the preliminary research and proposal processes and Paul Davis who, during a weekly visit, gave us a new perspective on our objectives. We appreciate all the help that our liaison, Jens Pedersen, and the Danish Cyclist Federation provided for us during our eight weeks in Denmark. -

August 2018 Newsletter

Den Danske Forening HEIMDAL August 2018 Doors of Copenhagen Medlemsblad Newsletter for the Danish Association Heimdal – Established 1872 THE DANISH ASSOCIATION “HEIMDAL” INC 36 AUSTIN STREET NEWSTEAD QLD 4006 Contact details: 0437 612 913 www.danishclubbrisbane.org Contributions meeting coming up soon, we We would love to share your news and stories. You are welcome to send emails with should all make a point of stories, news and photos to the editor for looking at the future of the publication. The closing date for the next club: what’s the next step? issue is 16 August 2018. We reserve the right to edit or not publish your contribution. What do we want to achieve, Any material published does not necessarily what can we do for Danes in reflect the opinion of the Danish Club or the Editor. Brisbane/Queensland/Australia? Do we want to become more Editor: Lone Schmidt political, take part in the Phone: 0437 612 913 Email: [email protected] immigration debate here and/or in Denmark. Provide Danish Webmaster: Peter Wagner Hansen Phone: 0423 756 394 lessons for kids/adults, open Skype: pete.at.thebathouse the club to restaurant activities Email: [email protected] such as a Saturday dinner club Web: www.danishclubbrisbane.org or Sunday brunch? And who’ll do it? Most current committee From the Editor members have been involved for over ten years now and it’s time for a fresh influx of ideas and muscle, if we want to maintain the momentum. Just had a good look at the club accounts before they went off to the auditors: what a year we’ve had! Although we cut back on concerts and other Spangsberg flødeboller - yum activities, Café Danmark and a variety of special events made it possible to generate the same income levels as last WELCOME TO OUR year. -

Københavnske Gader Og Sogne I 1787 RIGSARKIVET SIDE 2

HJÆLPEMIDDEL Københavnske gader og sogne i 1787 RIGSARKIVET SIDE 2 Københavnske gader og sogne Der står ikke i folketællingerne, hvilket kirkesogn de enkelte familier hørte til. Det kan derfor være vanskeligt at vide, i hvilke kirkebøger man skal lede efer en familie, som man har fundet i folketællingen. Rigsarkivet har lavet dette hjælpemiddel, som sikrer, at I som brugere får lettere ved at finde fra folketællingen 1787 over i kirkebøgerne. Numrene i parentes er sognets nummer. RIGSARKIVET SIDE 3 Gader og sogne i København 1787 A-E Gade Sogn Aabenraa .............................................................................. Trinitatis (12) Adelgade ............................................................................... Trinitatis (12) Adelgade (i Nyboder) ........................................................... Holmens (21) Admiralgade ........................................................................ Sankt Nikolai (86) Amagerstræde ..................................................................... Vor Frelser (47) Amagertorv .......................................................................... Sankt Nikolai (86) Antikvitetsstræde ................................................................ Vor Frue (13) Antonistræde ....................................................................... Sankt Nikolai (86) Badstuestræde ..................................................................... Helligånds (6) Bag Børsen ........................................................................... Sankt Nikolai -

Prisoners of War in the Baltic in the XII-XIII Centuries

Prisoners of war in the Baltic in the XII-XIII centuries Kurt Villads Jensen* University of Stockholm Abstract Warfare was cruel along the religious borders in the Baltic in the twelfth and thirteenth century and oscillated between mass killing and mass enslavement. Prisoners of war were often problematic to control and guard, but they were also of huge economic importance. Some were used in production, some were ransomed, some held as hostages, all depending upon status of the prisoners and needs of the slave owners. Key words Warfare, prisoners of war. Baltic studies. Baltic crusades. Slavery. Religious warfare. Medieval genocide. Resumen La guerra fue una actividad cruel en las fronteras religiosas bálticas entre los siglos XII y XIII, que osciló entre la masacre y la esclavitud en masa. El control y guarda de los prisioneros de guerra era frecuentemente problemático, pero también tenían una gran importancia económica. Algunos eran empleados en actividades productivas, algunos eran rescatados y otros eran mantenidos como rehenes, todo ello dependiendo del estatus del prisionero y de las necesidades de sus propietarios. Palabras clave Guerra, prisioneros de guerra, estudios bálticos, cruzadas bálticas, esclavitud, guerra de religión, genocidio medieval. * Dr. Phil. Catedrático. Center for Medieval Studies, Stockholm University, Department of History, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.journal-estrategica.com/ E-STRATÉGICA, 1, 2017 • ISSN 2530-9951, pp. 285-295 285 KURT VILLADS JENSEN If you were living in Scandinavia and around the Baltic Sea in the high Middle Ages, you had a fair change of being involved in warfare or affected by war, and there was a considerable risk that you would be taken prisoner. -

Denmark's Central Bank Nationalbanken

DANMARKS NATIONALBANK THE DANMARKS NATIONALBANK BUILDING 2 THE DANMARKS NATIONALBANK BUILDING DANMARKS NATIONALBANK Contents 7 Preface 8 An integral part of the urban landscape 10 The facades 16 The lobby 22 The banking hall 24 The conference and common rooms 28 The modular offices 32 The banknote printing hall 34 The canteen 36 The courtyards 40 The surrounding landscaping 42 The architectural competition 43 The building process 44 The architect Arne Jacobsen One of the two courtyards, called Arne’s Garden. The space supplies daylight to the surrounding offices and corridors. Preface Danmarks Nationalbank is Denmark’s central bank. Its objective is to ensure a robust economy in Denmark, and Danmarks Nationalbank holds a range of responsibilities of vital socioeconomic importance. The Danmarks Nationalbank building is centrally located in Copen hagen and is a distinctive presence in the urban landscape. The build ing, which was built in the period 1965–78, was designed by interna tionally renowned Danish architect Arne Jacobsen. It is considered to be one of his principal works. In 2009, it became the youngest building in Denmark to be listed as a historical site. When the building was listed, the Danish Agency for Culture highlighted five elements that make it historically significant: 1. The building’s architectural appearance in the urban landscape 2. The building’s layout and spatial qualities 3. The exquisite use of materials 4. The keen attention to detail 5. The surrounding gardens This publication presents the Danmarks Nationalbank building, its architecture, interiors and the surrounding gardens. For the most part, the interiors are shown as they appear today.